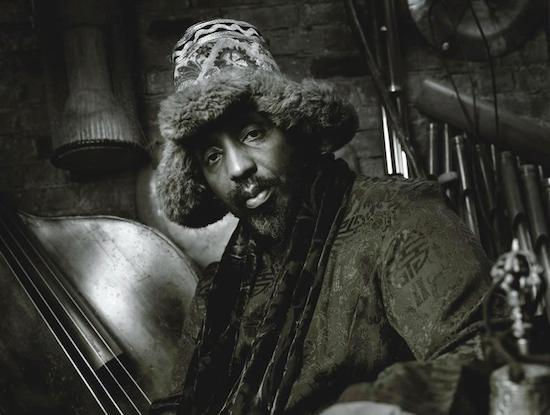

William Parker by Jimmy Katz

Whether you call it free jazz, improvised music, or "the new thing", we appear to be entering a moment when perhaps the most misunderstood of musical movements is enjoying a renaissance. Free jazz titan Pharoah Sanders is seeing as concentrated and broad a burst of critical praise as at any time in his life as Promises, his collaboration with Floating Points and the London Symphony Orchestra, is hailed as an early album-of-the-year contender. Keith Jarrett may have had to retire from playing due to illness, but recordings of his improvised solo piano concerts continue to appear; Charles Lloyd covers Ornette Coleman on his new LP with the Marvels.

And then there’s William Parker – the New York-based bassist, composer, poet, band-leader and free-jazz icon – who gained prominence working with Cecil Taylor during the 1980s and 1990s, and has gone on to produce one of the most extensive and eclectic discographies in 20th and 21st century music. He began 2021 with the release, on his own Centering Records label, of Migration Of Silence Into And Out Of The Tone World Volumes 1-10, a massive 10-disc set of work recorded between November 2018 and February 2020, which finds him collaborating with an extended cast of multi-instrumentalists and vocalists on a series of investigations of weighty issues and strident themes. It’s urgent and political, beautiful and compelling, lyrical and haunting in equal measure – no two discs are alike, yet the whole thing is unified by Parker’s creative vision, and by the shared joy he and his fellow musicians audibly bring to the task of mapping his idiosyncratic pathways through some vast and largely unexplored creative territories.

Free jazz attracts more than its fair share of cynicism – in part, one suspects, because those who don’t want to understand it assume playing it must be easy, incorrectly intuiting that all this stuff is just made up on the spot, with no rules, no "right" and "wrong" notes. Similarly, detractors question how a listener can truly appreciate music made outside of formal and creative boundaries, where anything goes and nothing is beyond the pale. Isn’t this all just a musical version of the emperor’s new clothes: a delusion shared by cunning creators and self-regarding audiences?

And so, over its life span, free jazz has spawned a contentious and often forbidding literature, as practitioners and adherents seek to bolster the intellectual foundations of the music. In this respect, the art form free jazz perhaps most closely resembles is – as the sleeve of the Ornette Coleman double quartet that gave the genre its name suggests – abstract expressionism. And, like an art-gallery catalogue, free jazz has acquired a tradition of substantial documentary buttressing. It’s almost as if the work isn’t allowed to stand on its own without accompanying theoretical treatises to explain its shape and texture, glosses from initiates to justify its worth. Accordingly, we’ve grown accustomed to the idea that we can’t possibly just sit and listen to Change Of The Century without fully immersing ourselves in Coleman’s explications of the concept of harmolodics; can’t let ourselves have an unmediated, honest, instinctive reaction to an Anthony Braxton album album without claiming to fully understand his theory of language music.

Parker swims against these counter-currents with evident ease. He has an overarching thought structure to his work which should satisfy those anxious to ensure artistic freedom comes with intellectual responsibility – but his descriptions of what he calls The Tone World reveal this conceptual underpinning is as much about mindstate and magic as it is musical theory. And in any case, the idea that Parker’s music is so free as to lack structure or recognisable audible landmarks couldn’t be further from the truth. He’s a composer – just one whose work relies on the improvisation and experimentation of his many well-chosen collaborators to bring his musical ideas to life.

That’s not to say that there aren’t moments of the magnificent, mammoth new box set that can conjure chaos. For instance, the fourth disc, Cheops, begins with a 13-minute track called ‘Entire Universe’, where the ensemble formed to play it – Parker on bass, drummer Rachel Housle, tubist Ben Stapp, Matt Moran on vibes, soprano sax player Kayla Milmine-Abbott and vocalist Kyoko Kitamura – veer between a relaxed swing and sudden explosions of atonality. Yet even when flinging itself between such apparent extremes, this is never music that pulls up any drawbridges. In his notes about the track, Parker singles out Milmine-Abbott, and writes that "she listens and feels and then waits for that magic moment and lets the music flow through her". It’s a vivid and vibrant explanation of what this music is for and how it works, and helps point out why it might have such tremendous power to excite and inspire and move.

tQ spoke with Parker via the pandemic-busting techno-sorcery of videoconferencing software towards the end of February, and found him as patient, warm, philosophical, sage and intriguing as his music.

Let’s start with the Tone World – and, particularly, this idea that gives a unifying title to the new box set about silence migrating into and out of it. What’s that about?

William Parker: Well, every time we play, we always start with silence. That’s a part of music. But at the same time, there’s continuous sound happening. If you look at music as a river of continuous sound, we just go down to the river, and we jump in with our instruments, and we partake in the activity of the river or ocean of sound. And we’re there for as long as we want that particular day: sometimes we’ll jump back out and do something else, then jump back in. But the music never stops – no beginning, no ending, it’s just continuous. And we go in and out of this world of music, this whirlwind of sound, our whole lives. If you look at music as a people, we, as a people, are trying to seek a promised land, and the promised land is the Tone World. And so we’re constantly migrating from different places to this place called the Tone World. That’s another way to look at it: we’re looking for this promised land which is music, which is sound, which is joy, which is enlightenment, and being in the light. And that’s also the Tone World. It’s the top of the pyramid – the apex of the pyramid. It’s all of these things.

Free jazz has never been an easy world to make a living in. What is it about this music that keeps you going, even when, on the practical and financial side, there’ll have been long periods where doing so has been very, very difficult?

WP: You don’t think about the money. We’re here to play for people who are chosen, who need this music to stay alive. And hopefully, one is able to survive, and travel the world. The only stars are in the sky, so it wasn’t ever about being a star. And you just had faith that you’d make some money. There’s no logical reason why any of this should make money, the way that the music business is. I know a lot of musicians didn’t make money, and they suffered. This is another important idea: it’s not about playing for people, it’s about playing for the Earth. When you’re playing and there’s no audience – if you’ve just got up in the morning and played your long tones and played your sound – the Earth is listening to that music. It goes to the Earth and it’s healing the Earth, and it’s a vibration that’s being put out. That’s what I believe.

But music is more than sound – that’s an important point. Once you define music as anything that’s beautiful – meaning that the poetry in the music is beautiful, the music in the poetry is beautiful, the poetry in the dance, the poetry in the garden, the poetry in trees, the poetry in little kids – then it’s not even so much about playing an instrument, it’s about how you live every day. I mean, we get up in the morning, we’re up, we’re interacting with people, we’re talking to people, we’re communicating in some way with other human beings. How do we communicate with them? How do we inspire them? How do we uplift them? How do we feed off of each other? That’s music too. And every once in a while you get to play, whether it’s at home or on stage. But it’s all connected, and you have to look at it in a way that makes sense for you, and have an understanding that you’re not a failure if you never play Carnegie Hall – you’re a success because you’re born.

Not everybody can be a musician, not everybody can be a poet, not everybody can be a dancer, but since music is everything, we can all be part of music. Music sometimes manifests as sound, but it also manifests as, you know, if somebody’s on the street and they’re starving and you bring them some food, that’s music. You see? When you’re a little kid, and if you’re lucky enough to have a grandma, and she makes you your favourite cake or pie, and she puts that pie on there and you eat the pie, that’s music! Just having a good game of sport: that’s music. Having just a good run through the woods – that’s music. All of these life-affirming things, what makes them work is the music in them. Music is everywhere. It’s about broadening our concept of what’s life. The art of living – how we live. That’s what it’s about.

There are quite a few of the sessions on the new box set where you didn’t play. And there’s one disc you do play on – Lights In The Rain – where most of the tracks are dedicated to Italian film directors. Presumably you were in the studio for the sessions you didn’t appear on…

WP: Oh yeah! I was like Quincy Jones in the booth there.

I was wondering if your role was like those directors: behind the camera and never seen, but the impact is all over the picture.

WP: The thing is, I don’t direct people that much. We rehearse the music, and… I may make a little suggestion here or there, because sometimes they don’t know exactly what to do. Sometimes – in fact, most of the times – I don’t know exactly how it’s supposed to be. I don’t really know the end result until we do it. But I do spend a lot of time pre-meditating or getting involved with the higher concept of the music. But then, when the musicians come, it takes a life of its own that I don’t want to interfere with.

How do you know that it’s been done right? That you don’t need to try it again?

WP: It’s intuition, and it’s trust; and it’s hopeful and wishful thinking that it’ll work out. It’s like, ‘Well, which way do we go – left, or right?’ Or, like, ‘When do you shoot the ball?’ When do you release it?’ And, ‘How do you know what to play when you’re playing?’ It’s a system that just seems to work, that really never fails: it’s a highly ordered system that’s very intuitive – all the last 50 years, of knowing what to play and how long to play it and when to let it go. This [box set] is a lot of different stuff, a lot of different ideas, so there was a lot of trust. But I like the way we work, and it’s a matter of faith, really, that things will work out. And nothing has really gone haywire, as of yet.

When there’s four or five of you playing, and you’re all really proficient players, and you’re all capable of going anywhere with what you’re playing in any given moment, how do you listen, and how do you know what you’re listening for?

WP: It’s not really a conscious listening. As you begin to play you step out of yourself, to another world, which we call the Tone World. And then you just listen in a different way. You’re not listening for anything, you’re really just in another realm. And it just happens magically. I mean, that’s the idea. We used to always say, ‘The lowest form of magic is logic, and the highest form of magic is what’s illogical.’ Because that’s the idea of magic – you’re supposed to do something that people can’t figure out! And the idea is that it is magic. Because there’s no reason for it to work, scientifically, except that, what you’re doing, it’s coming through you, and you’re letting it come through you, and you’re just relaxing and following. And it’s saying: ‘Grab my hand, William, follow me. Just relax. When you wake up, we’ll be in another spot.’ You know? And that’s how it is. We’re just going to sleep and we’re just following that music on.

Now, if I, through my musical training, interfere with that flow, then it doesn’t flow through, and it doesn’t work as well. I think that’s what you do in life. You practice, you train yourself to let go – to trust in music. That music comes from nature, and it’s got a particular order, and it’s beautiful. And all you’ve got to do is adhere to that order – figure out how to tap into that order that’s way older than us and that’s worked perfectly for years. And I think that’s what we try to do when we play, is just let go. You start when you’re young, or whenever you start playing, and every time you just try to let go more and trust. And then when it works, you sort of are tuned to letting it work. And once it works it just opens up – you open up; you fly.

It’s like saying, ‘You’re walking on water! Do you know you’re walking on water?’ And you say, ‘No, I didn’t know!’ And as soon as you say that, you sink. Once you become aware of what you’re doing, then you realise it’s just you doing it, and you don’t have these voices or angels or spirits – these sound forces – guiding you; and you say, ‘It’s just me! I don’t know how to walk on water.’ If I had to rely on myself to walk on that water I would sink every time. So I have to just relax into the spirit of music, and let that guide me.

Can you remember the first time you did that?

WP: I think I was playing at Rashied Ali’s place in 1977 or so. Ali’s Alley, at 77 Greene Street, playing with a group called Ensemble Muntu. It was time for me to solo, and I began to solo, and I began to lift my bass up, the way a saxophone player lifts a saxophone. And I was listening and playing, and I could see these colours, and I just was not there. I’d gone someplace else. And that’s actually when I came up with the phrase ‘the Tone World’. I had gone someplace else – I don’t know where I went. And I realised, next time I went there, that that was the Tone World I was entering. And it was like, ‘Wow, this is very cool.’

I became aware of it without spoiling it. Sometimes, you’re afraid: ‘If I become aware of what I’m doing it’s going to disappear.’ But I became aware of it without spoiling it, and I got strength from it. So it became an ally to me, to let go. And then it just happened naturally, every time I played.

There was a credo. Every time you play, you’re playing music to heal people and uplift people. And it’s gotta happen! It’s like doing brain surgery, or flying an airplane. Every time you take off, you’ve got people in the plane, you’ve got to land. Take off and land, take off and land, take off and land. You know? You cannot fail. That was the thing – you cannot fail. When you pick up your instrument you cannot fail. You can fail a spelling test, you could fail a math test, you can burn the vegetables, but you cannot fail when it comes to playing music, because that’s what you’re here for. You’re supposed to succeed in the flow of uplifting people. People are waiting for you! To listen to this music, to have their lives changed; to have you help them change their lives, to inspire them. It’s a very important job, playing music. That’s how I feel about it.

Watch William Parker, for free, on the first episode of Tusk TV

- The Music Of William Parker: Migration Of Silence Into And Out Of The Tone World Volumes 1-10 sold out of its first pressing in January; a second and final edition is expected in stock by the Aum Fidelity/Centering label at the end of March. Order here: [[[LINK – https://aumfidelity.com/products/william-parker-migration-of-silence-into-and-out-of-the-tone-world-volumes-1-10 ]]]]