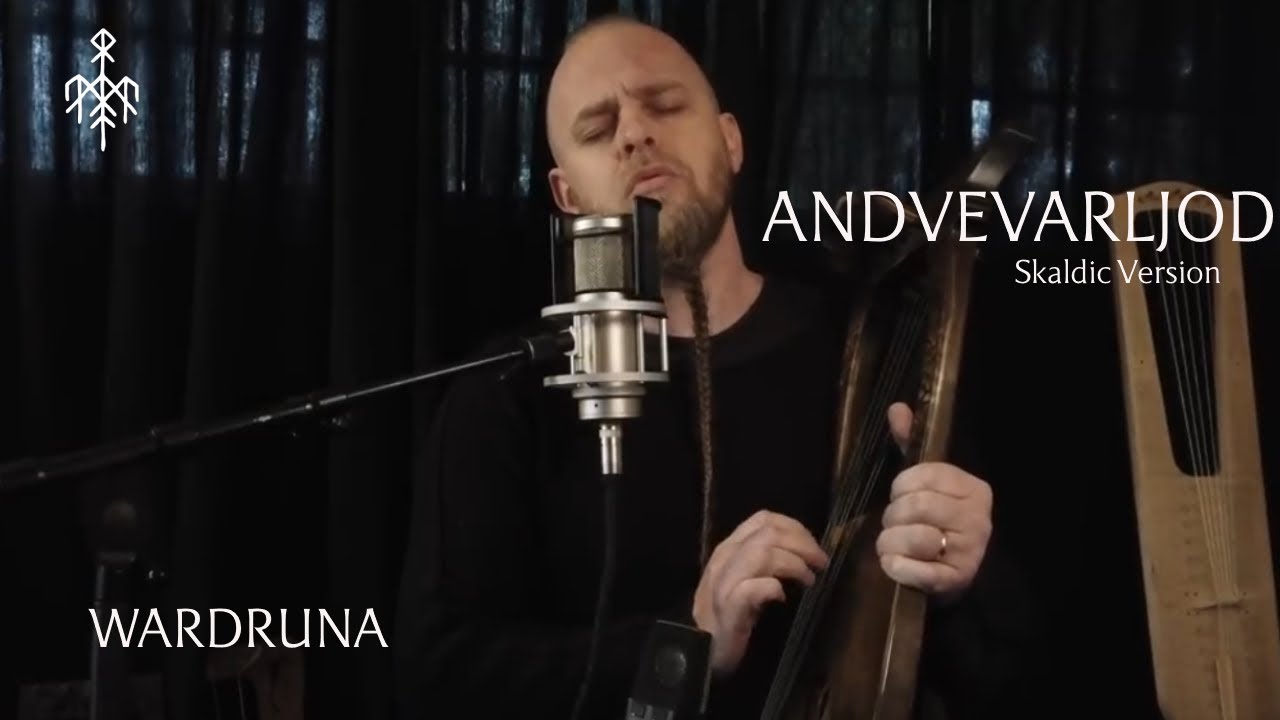

Still from Ragnarok featuring Einar Selvik

It would be easy to mock Norway’s Wardruna. Their name translates as “guardian of the runes” – they make music from goat horns, bone flutes and a replica of a German lyre from 500 AD. Frontman Einar Selvik has a long, plaited beard and sharp Viking-era haircut. He has solemnly delivered his odes to nature bare-footed in a freezing fjordscape: the video for ‘Lyfjaberg (Healing-mountain)’ has ten million views and counting, thank you very much.

But if you choose to laugh at Wardruna, don’t assume they are not in on the joke. As Selvik told me, their music “doesn’t have to be that serious or that profound or deep”. Selvik is bright-eyed, charismatic and sincere. In a cynical age, he gives us plenty of room to be affected by the magic he is conjuring. He employs tones, modes and drum patterns that speak down the ages and across the world: “I think it’s in our DNA, in a way, and I think since it’s such a global thing, that allows people to connect with it, no matter where they’re from.”

Wardruna make progressive music: it draws from the past, describes the present and plots the future. They break old instruments out of their museum cases. Selvik describes himself as a “multi-disciplinarian”. He teaches workshops and gives lectures. He strives – historically speaking – to be “standing on solid ground”. Creatively, he resists climbing the rootless tree. But he craves balance between education and naivety. What is the point of understanding the provenance of an ancient wind instrument, without then being able to play it for the first time like a child – with all the wonder and joy (and mistakes) that entails?

Wadruna’s new album, Kvitravn, meaning “white raven”, uses that corvid as a symbol of a bridge between worlds. Albino spirit animals populate mythologies from many cultures. In the Norse tradition, the ravens Hugin and Munin belong to Odin, representing thought and memory. In a livestream press event for the album, Selvik performed a solo stripped-back version of new song ‘Munin’ in the “skaldic” tradition. “Performing to the faceless,” as he put it, looking into the camera. Skalds were Nordic bards and poets. They held great power. They could name things and, in doing so, control them. Skalds carried the living memory of their people. They acted as a medium between past and present. Odin himself is a god of poetry.

On Kvitravn, Selvik soars over the music like the voice of memory as well as our 21st-century conscience. This is not just living history or historical reenactment, though Selvik supports that practice. For him, “knowing your roots gives you a sense of direction”. Nature has been speaking and we have stopped listening. The album is a cri de cœur to reconnect with nature. “And it’s not this romantic idea – dreaming to a distant past where everything was so much better, because I don’t think it was necessarily!” he says. In the ancient past, humanity fought nature and tried to control it. Nowadays, we have almost totally removed ourselves from nature. We were reminded of this in the Spring of 2020 when the general population was hushed enough to notice it again.

Wardruna’s music explores a “friction” (a word Selvik uses repeatedly) between our romantic conception of what “paganism” stands for, how that differs from what it meant in the past, and our melancholy at nature’s absence now. Selvik goes out “hunting” for songs in the open. He writes them intuitively, though he describes himself as musically “illiterate”. He performs these songs in dramatic natural spaces. He sees Wardruna’s music as “a way of connecting to those energies in the absence of nature. It becomes a bridge. It becomes a way of getting in touch with these things I think a lot of people in modern society are feeling a loss of, or a longing for. Some form of connection to our surroundings.”

Einar Selvik portrait by Arne Beck

I experienced the uncanny effect of Kvitravn making one of my rare 2020 trips into the centre of London. The drums seemed to reverberate off the homes of Roupell Street as I made my way from Waterloo station on a cold December evening. Roupell Street is constituted of 19th-century terraced housing. It is a living conservation area; a portal as much as a television and film set. In this context, Wardruna’s music seemed to trace a beautiful sadness in the architecture of the urban landscape – this street frozen in time.

That said, listening to Wardruna really comes into its own when sitting out in nature. It might be timeless music, but its roots in the natural environment creates a synergistic effect. Suddenly, potentially – in Selvik’s mind – “two plus two becomes five”. In his book The Old Ways, Robert Macfarlane posits that there are two questions that we should ask of a “strong landscape”: “firstly, what do I know when I am in this place that I can know nowhere else? And then, vainly, what does this place know of me that I cannot know of myself?”

Wardruna might be useful in answering these questions. They use musical techniques – including drones, overlapping frequencies and crooked beats – that have been used in ritual for centuries, millennia even: from shamans in Stone-Age long barrows through to medieval church music. But to what end? Selvik prefers not to see himself as a preacher but he has a core conviction: “I do believe strongly that it would benefit us all if we applied a more animistic view of nature. I think we got off track as a species as soon as we took the sacredness out of nature. That is not necessarily a spiritual thing. It’s an attitude. It applies whether you’re a spiritual person or a religious person, or not. It’s an attitude: viewing nature as something that’s sacred, something important, something we are a part of. Not something we are the rulers of.”

In basic terms, animism is the exploration of the lifeforce and inherent impetus of our surroundings. We can tune into the frequencies of the natural world and perhaps alter them. It has some parallels with panpsychism, which posits that everything has a mind of its own (of sorts).

The philosopher Dr Philip Goff, author of Galileo’s Error – an authority on consciousness and defender of panpsychism – distinguishes the behaviour of the smallest bits of matter, such as an electron, and its intrinsic nature: “All we get from physics is this big black-and-white abstract structure, which we must somehow colour in with intrinsic nature. We know how to colour in one bit of it: the brains of organisms are coloured in with experience. How to colour in the rest? The most elegant, simple, sensible option is to colour in the rest of the world with the same pen.”

If animism and panpsychism strike you as ridiculous concepts, perhaps it helps to see the ridiculousness in everything. Philip Pullman is a fan of Goff’s. Pullman also draws on Norse mythology in His Dark Materials and the spirit animal “daemons” of its characters. He has also said on the record that his daemon would “most likely” be a raven. Selvik has taken “Kvitravn” as a stage name. With Wardruna, Selvik is the raven that has flown off with Goff’s pen and is colouring in the world with his music.

What does this mean for us in the British isles? All of this Norse and Nordic thinking is over there isn’t it? How is it useful to us now, at a time when our relationship with the European mainland has been severely tested, especially in trading terms? At least the Vikings were effective, if forceful, when it came to trade. I think it boils down to trying to recover our sense of humour.

I’ve just finished reading The English Heretic Collection by Andy Sharp. Sharp initiated the English Heretic project in 2003 as a parodic response to English Heritage’s “entirely dry rendering of history”. Like Selvik, he noticed the difference between an adult’s and child’s engagement with history. He set out to document the occult side of England’s past. The book is fascinating and often pseudo-academic in tone (yes, I’ve learned a lot of arcane words). But Sharp writes with a glint in his eye. The project dares you to take it too seriously. In this respect it is quintessentially English: it deploys irony as a means to protect itself from criticism.

There are many striking ideas and explorations in the book. Sharp returns to the Greek concept of katabasis often. Meaning a journey into the underworld, it suits the modus operandi of the collection. But at one point he offers an intriguing alternative definition: “It can also mean a journey from land to sea. The shoreline is a metaphor for the unconscious, the journey towards it a mental peregrination.”

Sharp zooms in on Orford Ness as a place of heretical interest. Orford Ness is a shingle spit off the coast of Suffolk which is now a nature reserve managed by the National Trust. In the naval wars with the Dutch and French in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries it was a key defensive position. In the 20th century it was co-opted by the military for seventy years of experimentation into using airplanes as weapons. It is an intense site. But set a few miles further back from the coast, towards the village of Woodbridge, is Sutton Hoo.

Sutton Hoo was excavated in 1939 on the eve of the Second World War and that conflict’s catastrophic opening up of a major fissure within Europe, in the fight against the Nazis. What was uncovered at Sutton Hoo was a treasure trove of Anglo-Saxon grave goods belonging to a warrior-leader figure. Thought to be from 625 AD, the goods pre-date the Vikings landing at Lindisfarne off the Northumberland coast in 793 AD. Some items, such as the shield and drinking horns, have attributes in common with Scandinavian equivalents. Walking around Sutton Hoo feels like connecting to the primal unconscious Sharp associates with coastal regions. The site provides evidence of historical trading bonds with the Nordic people that positions it as the western coast of a shared culture bounded by the North Sea, as much as the east coast of modern-day England.

The archaeologists uncovered a lyre at Sutton Hoo, suggesting the grave of a musician and a poet as much as a warrior. Sutton Hoo greatest treasure is a world-famous helmet that sits at the heart of the British Museum. It confirms that when we consider Wardruna’s music and connect with its message, it is because of a shared northern European heritage. From 1017, King Cnut ruled over England, Denmark and Norway together for nearly two decades. We were once part of the same kingdom.

Selvik sees Britain and Scandinavia’s kinship as deeper, because of “shared mechanisms”: “Polytheism: well, in any nature-based religion of course there are local varieties. My traditions are created and shaped by my river and my resources. My forest and yours are shaped by the same parameter. So the concepts are exactly the same and on many levels our nature is very similar as well. […] I definitely see that it’s in many ways the same tradition – with local varieties. My wrapping is a little bit different from what yours will necessarily be.”

Wardruna by Kim Öhrling

The palimpsest of Viking culture in Britain is clear in 2009’s Valhalla Rising, directed by the Dane, Nicolas Winding Refn. In the film, Mads Mikkelsen plays ‘One-Eye’, an Odinic protagonist held captive in the glens of Scotland. He escapes and soon encounters a group of Christians who want to reach the Holy Land. Once at sea, they encounter heavy fog and wind up in Newfoundland, where they begin a series of violent encounters with the native skrælings. The holy band soon descends into madness.

The whole of Valhalla Rising was filmed on location in Scotland. The film’s second half was filmed in Glen Affric, west of Loch Ness, which doubles for Canada thanks to its 600-million-year-old forest. The forest existed before the continental drift that separated Canada from the British Isles. In this way, Scotland is not just the filming location for Valhalla Rising but also a geographical and historical centre of the Viking legend.

The film can be read as a comment on cultural imperialism, and about what happens when primal forces come up against more “advanced” human constructions. It is po-faced about its subject matter, visually stunning, and also pretty silly. In a similar vein, I think one of the reasons a heavy metal audience is comfortable with Wardruna (a largely unamplified group, apart from Selvik’s collaborations with Ivar Bjørnson of Enslaved) is the heavy-metal crowd’s willingness to accept the proximity of the profound and the ridiculous.

That, alongside heavy metal’s keen interest in the primal forces that continue to motivate us. As Selvik sees it, this is also what frames Wardruna as “world” music: “I can go to the East or many other places and find things that are so strikingly similar to our own traditional music. I think that’s part of why these really old, primal musical expressions speak to us on a deeper level, or are a recognisable thing. I think that’s one of the reasons why we seem to transcend these language barriers, and cultural barriers, and the fact that our audience is so diverse – all of these things. Also in terms of age, and other kinds of music our audience listens to. It moves beyond those borders.”

Selvik stresses that Wardruna’s music is not only bound up with the Viking Age (running from 780 to 1070 AD), but stretches further back – up to ten thousand years ago. Then, the British Isles were connected to mainland Europe by a landmass called Doggerland. Early mesolithic hunter-gatherers migrated across it northwards.

It was long thought that a tsunami wiped out Doggerland about 8,200 years ago. This was triggered by the “Storegga” submarine landslides off the coast of Norway. Recent research suggests that this Ragnarok-like event might not have wiped out the whole land mass and its people. Instead, over subsequent millennia it was the slow creep of climate change and rising sea levels that submerged the remaining archipelago.

When Selvik tunes into nature he traces how it is changing. The current climate emergency cannot be separated from the messages of Kvitravn. The album reaches a climax with ‘Andvarljod’ (‘Song Of The Spirit-Weavers’) and its opening sample of thunder clouds gathering. The song concerns the Norns, who from Norse mythology are arbiters of our fate. Wardruna released a shortened, skaldic performance of the song on the Winter Solstice – also the day of a portentous conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn. In astrological terms, the conjunction brings with it significant change for good, or ill. On that darkest day, when "summer is born" as Selvik put it in his introduction, the song heralded a potential changing of the tide.

On the ten-minute-long recorded version on the album, Selvik pushes his singing to new heights, against a chorus of female voices. He told me it is with “a new level of enjoyment singing, sort of finding my own resonance, in a way. When you hit those notes it really resonates within as well. Then you know you’re on to something.”

In the song, Selvik finds a power in his delivery that recalls Norse enthusiast Robert Plant. In the live version of ‘Stairway To Heaven’ on Led Zeppelin’s The Song Remains The Same from 1973, Plant adlibbed to the Madison Square Garden audience, “Does anybody remember laughter?” Easy to scoff at Plant’s melodrama here, but I’ve seen a change in the British character in recent years that makes his question more urgent.

For a country renowned for its biting sense of humour and self-effacement, we have become more brittle, quicker to anger, and seem to be losing our grip on our long-held national sense of humour. That has coincided with a period of nationalism that has seen us turn our backs on our European identity. Wardruna are offering a way back.

We can laugh at Wardruna if we want. In doing so, we have to recognise that we are laughing at ourselves. Perhaps that is Einar Selvik’s greatest gift to us.

Kvitravn is released on January 22 through By Music For Nations/Sony. Einar Selvik is headlining That Jorvik Viking Thing in February