Venom, 1981

As heavy metal nears the end of its golden jubilee year, its rude health as a genre is exemplified by its ubiquity. There isn’t a continent – with the honourable exception of Antarctica – where it doesn’t flourish. This music, which initially only took root as an outsider interest in a handful of countries, now blossoms in the most unlikely of places and there seems to be little that various international religious, legal, political and linguistic obstacles tossed in its path can do to prevent its spread.

But this cultural agility isn’t just a geographical phenomenon. While there remains a long way for heavy metal culture to travel, especially in some subgenre scenes, it has undoubtedly come an impressive distance in terms of inclusiveness. Type “feminist black metal” into a search engine and you’ll see how big the gulf is that separates us from the almost inevitable Googlewhack of two decades or so ago. Anyone who has read the most anticipated heavy metal book of recent months – Rob Halford’s excellent Confess – will have had chance to meditate on the old-fashioned assumption that heavy metal has homophobia ingrained into it; this appears to be either a position previously overstated or one that simply doesn’t apply that rigidly any more. And if there are any genuine metalhead white supremacists reading this… well, you’re a blinkered idiot and you can prise my Duma, Boris, Divide And Dissolve, Tetragrammacide, God Forbid, Melechesh and Al Namrood albums out of my cold, dead fingers.

But when it started in 1970 and for most of the decade that followed, heavy metal in the UK was very white, very male and very working class. The class aspect of this shouldn’t come as that much of a surprise – it was born out of an industrial accident after all. Tony Iommi was working as an arc welder in a sheet metal factory in Aston, Birmingham when, on his last day, he was shifted to a manually controlled metal crimping vice and, due to lack of training and faulty machinery, he crushed the tips of the two middle fingers on his left hand, until they tore off.

A guitarist already skilled far beyond his years (after a period of intense depression) he instituted many smart hacks to get round this obvious disadvantage. He took succour from recordings of Django Reinhardt, he modelled prosthetic finger tips for himself out of plastic from a melted Fairy Liquid bottle, used light gauge banjo strings which were easier to hold down, wrote songs in E meaning the bass string of the guitar could ring out creating a fuller guitar tone, applied vibrato in order to compensate for an inability to play full power chords comfortably or precisely and eventually down tuned his guitar. All of which had a partially funnelling effect on the nascent sound of metal, emphasizing a new primitive-sounding, bludgeoning heaviness to complement rock’s already extant musical sophistication.

Ozzy Osbourne, famously, did six weeks in HMP Winson Green in Birmingham after failing to pay fines relating to a burglary charge, but this pathetic stab at becoming a criminal really only came about after he failed as a factory worker. He had formerly worked alongside his mum in the Lucas factory where his job was honking old fashioned car horns to check they were ‘in tune’, and his longest stretch of gainful employment pre-Sabbath was on the killing floor of a Digbeth abattoir. Bill Ward has told me that kids had two options on graduating from the comprehensive that he attended: the factory or the army.

By the end of the decade things in the UK hadn’t changed that much. As the exciting New Wave Of British Heavy Metal sound developed it would be incorrect to say that this was a solely working class development but characters such as doctor’s son Robb Weir of Tygers Of Pan Tang and university educated Montalo of Wytchfinde were the exception rather than the rule.

Certainly, the bands who have gone on to have the most lasting impact from this loose scene – Iron Maiden (pre-Bruce Dickinson), Def Leppard and Venom – were working class and lived in areas that were inner city and run down, heavily industrialised, or both. In fact if Conrad Lant, an aspirant teenage musician with a taste for punk rock and heavy metal, had a problem, it was that by the time he graduated from school in 1978 he wasn’t destined for a noisy assembly line or dangerous machine shop because there weren’t that many factory jobs left for him to apply for.

The year before he changed his name to Cronos, and became bass player and singer with the newly minted and foundational extreme metal band, Venom, Lant’s concerns were far more quotidian. On his last day at high school he faced the same existential question as the rest of his classmates. He laughs: “We all looked at each other and said ‘What do we do now?’ We’d never had any education about how to get a job so we all stood there saying, ‘Where do we go? Do I just go home now?’”

Crappy careers advice aside, school wasn’t a total bust flush. He attended Ralph Gardner High School in North Shields – which had boxing (rather than football, cricket or rugby) as its chief sport for boys. Fearing for his safety (the Lants had moved up from London to Tyne and Weir when he was eight casting him as something of an outsider starting at a relatively tough school) he shaved his head before his first day but once acclimatised, never cut his hair again.

The curriculum had an emphasis on practical subjects but even the foregrounding of metalwork and woodwork was a throwback to an era that had alredy elapsed, so students treated them with disdain: “It had become apparent to everybody by the mid-70s that there were no fuckin’ jobs to go to, y’know. They were joke lessons that nobody took seriously.”

He adds: “During the entire time I studied metalwork, all I made was a tiny, hand-sized vice.” With a nod to the key local industry that had been forced to its knees he adds: “That was the entire sum of it. I mean how the fuck was I supposed to build a ship with that knowledge?” This was a set of unique, alienating circumstances separating his experience from that of his parents: “The opportunities were all there when they left school. It was just after the war, the country needed rebuilding but by the 70s… We were living in a broken land with a whole load of youth who had no future.”

It’s because of this he can relate to the experiences of Ozzy Osbourne: “No wonder the guy ended up in jail because, well, needs must. You’ve got to put fucking food on the table. Ok, he made a bad decision and resorted to crime but fucking hell… who didn’t? It was just the times.”

After witnessing the Sex Pistols and the Bromley Contingent’s notoriously foul-mouthed run in with Bill Grundy on the Today show in the December of 1976, the 13-year-old Lant became radicalised – he knew exactly what he wanted to do. Luckily for him a switched on music teacher would let him and a couple of other mates skip maths and chemistry lessons so they could learn to play Beatles, Status Quo and AC/DC numbers on the guitar instead. This led to the high school outfit Album Graecum who blasted out ragged hyperspeed covers of Bowie and T-Rex numbers but with a pronounced filter: that of the angry teenage punk fan: “We played ‘Ride A White Swan’… but five times too fast!”

Cronos remains to this day a relatively fit guy and was, until a serious accident, an accomplished rock climber. This interest in keeping fit kicked off at school because he had been considering a career in the military (even though anyone who has seen a photograph of Venom on stage may find this implausible): “A lot of my friends went into the army. They went over to Ireland during the Troubles. They’d come back telling all of these stories about having bullets flying past their heads. When you’re a kid it just sounds exciting.”

A mishap put paid to this however: “We all had weapons. Slingshots and 1.77 air rifles. There used to be this big area called the wood yard where we’d go rabbit shooting. One day we were bored because we couldn’t find any rabbits, so we decided to play soldiers and started shooting at each other. And I just got the unlucky pellet. I was hiding behind a piece of wood and jumped up and the bullet went straight in my eye [laughs].

“I’m still blind in the right eye. I was lucky really – the pellet went round inside my eye socket. It’s still lodged there. But I figured it would stop me from getting accepted into the forces so I didn’t bother applying.”

But with factory work and the forces off the menu there was one other option the straight life had to offer in terms of employment.

Venom crawled out of a landscape which is all too hard to imagine now if not experienced first hand, although you can inhale dank draughts of it if you know where to look. Images of the concrete bones of the new provincial brutalism sticking through the cratered flesh of bomb-harrowed waste ground form the backdrop to Mike Hodges’ Get Carter and can be glimpsed briefly in Peter Care’s short film Johnny YesNo. Just like the factory-heavy East End of London, just like the munition works in cities like Birmingham, Coventry and Manchester; just like the Atlantic port of Liverpool and the North Sea port of Hull and the coastal targets of Plymouth, Glasgow, Swansea and Belfast, the docklands of Newcastle were hit hard and heavy during the blitz.

The fish quay and the shipyards in North Shields were among the only structures that warranted immediate repair in the pre-war years. The young Conrad Lant had played on the former as a kid and aspired to work at the latter once he left school: “I had the opportunity of actually putting my waders on and going out on the trawlers. I thought, ‘Well, if all else fails, I can do this.’ I went out a few times with the lads just sort of helping out, not as a paid job.

“On the quay there was a fish market. The boats would come in early in the morning, the fish would get unloaded under canopies and all the guys would be there putting out sheets of white paper marked with black chalk representing how much they’d caught and the type of fish.”

Fate intervened in a decisive way however. Lant talks about an incident which he still holds to be the most frightening thing that has ever happened to him: “After helping out here and there, the first time I was supposed to properly go away on the trawl-out boat, I missed it. I turned up late and they went without me. And the boat didn’t come back. They hit really bad weather. I heard some stories from other boats who said that they’d seen the guys not long before it happened. I’d been so close to going the wrong way [laughs nervously]. I still think about it. You’re like the guy who didn’t get on the flight, y’know and it haunts you. Especially when it’s that close. That traffic jam, that you get stuck in, and you’re cursing it at the time… it can turn out to be a blessing, y’know.”

He continues: “But most of the buildings that got bombed during the war were just left in ruins. I remember my mother telling us about this tobacco factory, how people used the basement of it as a bomb shelter. But one night Adolf and his boys hit it hard in the Blitz, killing a load of them. It was because this was a heavy industry area. The Nazis had to take out the shipbuilding on the Tyne and south of there, Sunderland got hit hard as well.

“Nowadays it’s all posh flats, with very expensive beautiful views. You’ve gotta be very rich to own a flat there, which is quite a change from the terrible terrible state it was in when I was growing up.”

His school band Album Graecum (“it’s Latin for dried dogshit or something”) weren’t exactly making waves so when he turned 14, Lant threw his lot in with some older lads who had already left school and were in a band called DwarfStar. Handily, they practiced once a week in a church just round the corner from where he lived. They were covering Deep Purple and AC/DC but the music just wasn’t aggressive enough for him besides, the band practiced for years but never played a single gig.

When his question on leaving school – what do I do now? – was finally answered, he ended up down the dole office in order to sign on: “They would have these two inch by two inch cards on the wall with different jobs on them. You’d have to pick one, go over to the desk and say, ‘I’m interested in this.’ I told them I was into art and music, so they said, ‘Here, you can go for this job.’ It was to be a piano tuner. I was like, ‘What the fuck? I can’t even play the piano, let alone tune one!’ It was an example of how they had no plan for how to deal with all of this unemployment.”

Persistence at the job centre actually paid dividends six months after he left school. Figuring he liked music and liked art, he took a card marked ‘Audio Visual’ to the counter and found out there was a part time job going at Impulse Studios in Wallsend (which would become a notable location in the NWOBHM story, as some key albums that came out on local label Neat would be recorded there). Finally, there was a job for the wannabe punk rock, trainee son of Satan that was more suitable than tuning pianos… And it was via the studio that he met a local band called Guillotine who were looking for a new guitarist: “Meeting up with those guys, seeing that they had a decent drum kit, Marshall stacks and that they were a lot more together than the guys in DwarfStar, made me think, ‘This is a step in the right direction, toward being in a fucking real band.’”

Guillotine rehearsed in a different church hall. A big, high-ceilinged room attached to Westgate Baptist Church in Arthurs Hill. Lant says: “When I first went down to meet them they were a covers band. They did ‘Doctor Doctor’ by UFO. It was obvious the guitarist [Jeff Dunn] was trying to model himself on KK Downing. He had the flying V, the blond hair, the moustache. I saw him and thought, ‘Here we go.’ The drummer [Tony Bray] was a big Deep Purple fan who was into glam rock. He would come to rehearsal with bright yellow boots on and different colours sprayed in his hair. They already had a singer called Clive [Archer].” Lant was on second guitar and the line up was completed by Alan Winston on bass – although he didn’t stay long. Winston quit a week before a small gig, leaving Lant to switch instruments: “I borrowed a bass guitar and had to learn the songs. I only played them on the top string, but I plugged into my Marshall stack through all of my Big Muff pedals and that’s when the bulldozer bass sound was invented. It created this huge raaaaaawwrrrrr! bass sound. It was like,’Oh, I’m gonna stay with this instrument!’”

Lant told them that he thought they should be doing original material and it turned out both he and Dunn had been writing songs. They pooled their ideas and came up with their first set, which they eventually recorded simply by placing an old Sony cassette recorder with a small external mic at the other end of the large hall and taping one of their practice sessions. This recording has recently become available as part of the Sons Of Satan early recordings and demos compilation and features the tracks ‘Angel Dust’, ‘Buried Alive’, ‘Raise The Dead’, ‘Red Light Fever’ and ‘Venom’.

If it seems odd that the band who ushered a less ambiguous and more approving brand of Satanic glamour and fascination into the heavy metal genre honed their skills in a church hall, the reason is somewhat prosaic: “The priest didn’t have a clue [laughs]. If he’d known we were standing in his church singing ‘In League With Satan’ he would have thrown us out.” The band – who all had day jobs met up once a week at the church to play. In fact, at this point Lant was still playing with DwarfStar in the evenings, so while the sound that would eventually become the most notorious, Satanic subgenre of rock ever birthed, True Norwegian Black Metal, he was actually attending two different churches a week… religiously.

Right from the beginning it was Lant who was pushing the band into much darker lyrical territory. While Dunn was responsible for the songs that hymned more traditional rock & roll pursuits such as sex and drinking, Lant tended to focus in on all things occult. He explains: “I’ve always loved lyrics, so it’s always been the thing that I’ve mainly concentrated on. I’ve always been fascinated with Rush for example, the way Neil Peart would write songs with science fiction themes for albums like 2112. That’s been a massive influence on the way I write.

“If I can, I write lyrics to make people think, ‘What the fuck’s he talking about there?’ With a title like At War With Satan – the number of people who ask, ‘Does this mean you’re fighting with Satan or against him?’ And I’m like, ‘Dude… that’s for you to work out.’ You have to read the lyrics to see which angle I’m coming from.

“I wasn’t really thinking of shocking people though. I used to listen to Sabbath and Ozzy would go, ‘What is this that stands before me? … Oh god help me!’ And I would think, ‘What the fuck are you doing!? You just spoilt the song!’ So I thought, ‘Right – well I’m gonna be that thing that stands before you. I wanna be that fucking demon who you’re afraid of.’ So I wanted to do that lyrically because I knew nobody else was doing it. I said to the guys one day, ‘I’m gonna be the personification of the thing that even Satan is afraid of’ [laughs]. I’m gonna be the baddest of the bad, y’know. You want someone to be Dracula? Ok, I will put my hand up for that and be Dracula because nobody else wants to. That sort of thing didn’t shock me. I love horror movies and books. When I see some of the younger bands, especially the visual side of them, like Dimmu Borgir, Immortal, bands like that, that’s exactly where I was going.”

Despite writing to various labels, they didn’t get any interest via the tape, which was admittedly quite lo-fi. The sound, scrappy as it already was, had been overwhelmed by natural reverb created by the size of the hall and their curious decision to place the tape recorder as far away from themselves as possible. Lant found this frustrating as he was getting used to seeing local heroes such as Raven and Tygers Of Pan Tang gaining traction outside of Newcastle – he was aware a scene was developing in real time as he was watching from the sidelines. They upped the ante by indulging in what could be called, by today’s standards, a rebranding exercise.

On the suggestion of their roadie, they changed their name from Guillotine to Venom but also adopted stage names themselves. Lant became Cronos, Dunn became Mantas, Bray became Abaddon and Archer, in for a penny, in for a pound, took on the name Jesus Christ. Cronos says: “It just made sense to rename ourselves as well. We all decided on it really. It just seemed daft to call ourselves Venom – the Sons of Satan – featuring Conrad, Jeff, Clive and Tony.”

Cronos realised that he somehow needed to make a connection between his band and his day job at Impulse. He had trained as an assistant engineer and tape operator and in April 1980 he agreed to work evenings with the senior engineer on late sessions for no extra pay, in return for the band getting a session for free. He then secured a reel to record the session on by washing the studio owner’s car.

His only desire was to get a workable demo together as his band was stuck in stasis without one. With three tracks ‘Angel Dust’, ‘Raise The Dead’ and ‘Red Light Fever’ in the can, they had a cassette to send to people where you could actually hear what was going on.

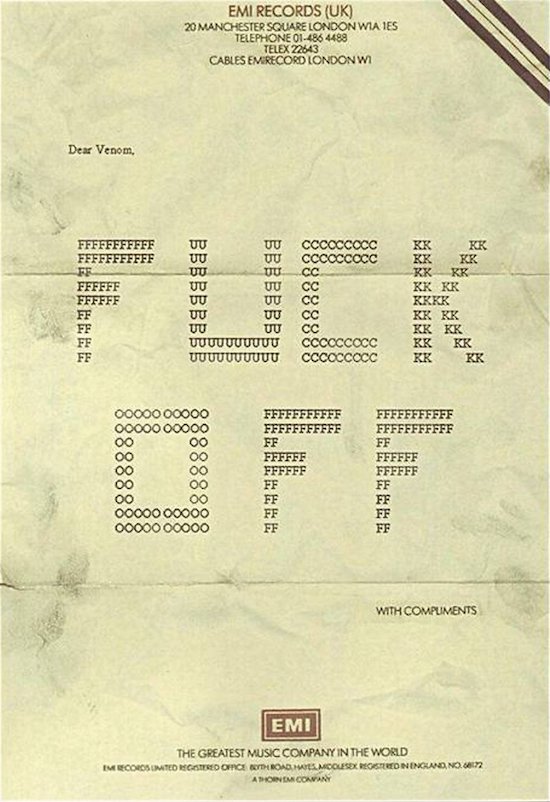

When sending these demo tapes out he even went as far as using a pencil to wind the cassette forward slightly past the run in tape, so that if the tape was returned he could tell if it had been listened to or not. In one memorable case, that of EMI, the tape had been played but the reaction was not great. Someone painstakingly used scores of keystrokes on a manual typewriter to send them back a simple message: “Dear Venom, FUCK OFF”.

But someone was paying attention. Heavy metal gatekeeper, Geoff Barton of Sounds played the cassette in the office of the weekly causing all the other journalists present to vacate the room. Remembering the occasion for Classic Rock some time later he said: “I had never heard anything like it. It was like being a living, breathing, tormented character in an Exorcist movie. Only Venom didn’t just make Linda Blair’s head revolve like some child-friendly funfair roundabout; instead the band ripped her cranium from her shoulders, brandished it triumphantly above their heads and then smashed it down through splintered floorboards, to be reduced to grey ashes in the incandescent kingdom below.”

He put all three songs on his Sounds playlist and suggested that Neat records think seriously about giving the band a deal – which they did. Neat suggested that Venom go back to Impulse in order to record one of the studio’s £50 demos – essentially a cash strapped band would record as many songs to two inch tape as is possible in four hours with no overdubs and little other than live to tape playing. This left them with yet another demo featuring ‘In League With Satan’, ‘Angel Dust’, ‘Live Like An Angel’ (with Cronos on vocals), ‘Schizo’ and ‘Venom’. And on the basis of that Neat offered to put out their first record. Lasting damage had already been done to Jesus Christ’s faith in the band however and he left by mutual consent. As Cronos was already singing ‘Live Like An Angel’ in their live sets (while Jesus Christ had a costume change), it seemed natural for him to step up to the plate and Venom the power trio who were just about to release their debut single, ‘In League With Satan’ were born. Before long, two of the most important albums in extreme metal – Welcome To Hell and Black Metal – would be unleashed on the world.

Like most young bands, Venom weren’t thinking about heritage, they could only see the next staging post. Once Cronos had a band he wanted a recorded document on cassette. Once he had a tape he wanted a more professional sounding demo. Once he had a more professional sounding demo he wanted a record deal. At no point was he thinking about the 40-year legacy of the group or the impact they would have across the Atlantic on the developing thrash metal scene or up in Scandinavia in the burgeoning black metal movement: “No one said, ‘Oh we’ll still be doing this in 20 or 30 years time.’ But at the same time, we did try and pace ourselves. We didn’t want to burn up and be gone quickly. We weren’t selling millions of records so there wasn’t much money to play with but we did stuff that was unheard of like hiring the Hammersmith Odeon and selling the fucker out when nobody really knew who we were. We weren’t in a rush. We did feel like we had all the time in the world.”

When talking about all of the multiple strands of metal that the band would go on to influence, it’s perhaps easier just to say that Venom were the first truly important band when it came to extreme metal – the Satanic Geordie midwives to all of the astounding leaps forward that happened during the 80s, 90s and beyond: “I love the idea of extreme metal. I just think you can’t go too far… so long as it’s just within the music y’know. The further the better, the more extreme the better, the more notorious, the more hardcore.”

But of course, now it’s 40 years later he’s obviously had a chance to reflect on Venom’s legacy but doesn’t seem overly obsessed with it: “I just think when people say, oh Venom started this, or Venom started that… what I would say is that we were a catalyst. I think all of this music we see around us today was always gonna happen, I just think somebody needed to kickstart it, and that’s what we did.”

And he laughs, because he knows it’s far beyond good enough.

Sons Of Satan by Venom is out now

With thanks to Michael Hann