In 1917, Sigmund Freud wrote that “melancholia is in some way related to an object-loss which is withdrawn from consciousness.” He distinguished this from mourning, our way of processing the disappearance of a specific something from our lives. We can pinpoint what we mourn, but melancholy is harder to parse, churning away in the slippery underdark of our minds.

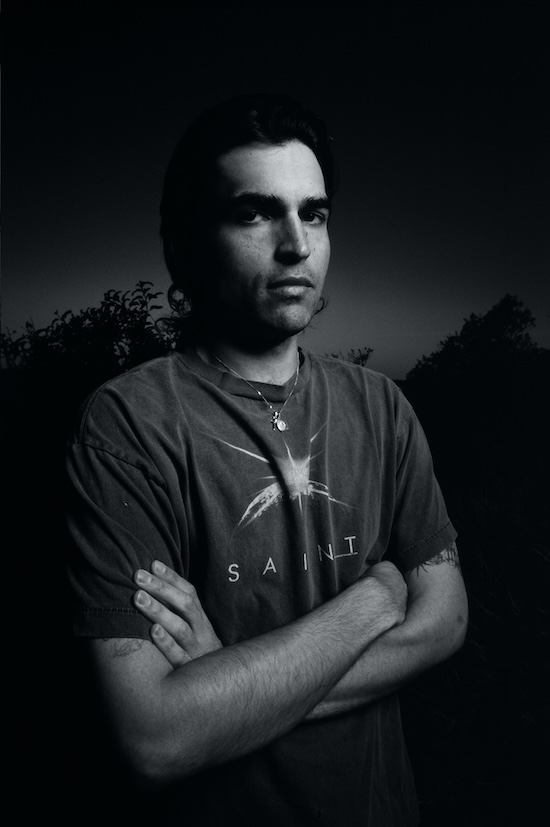

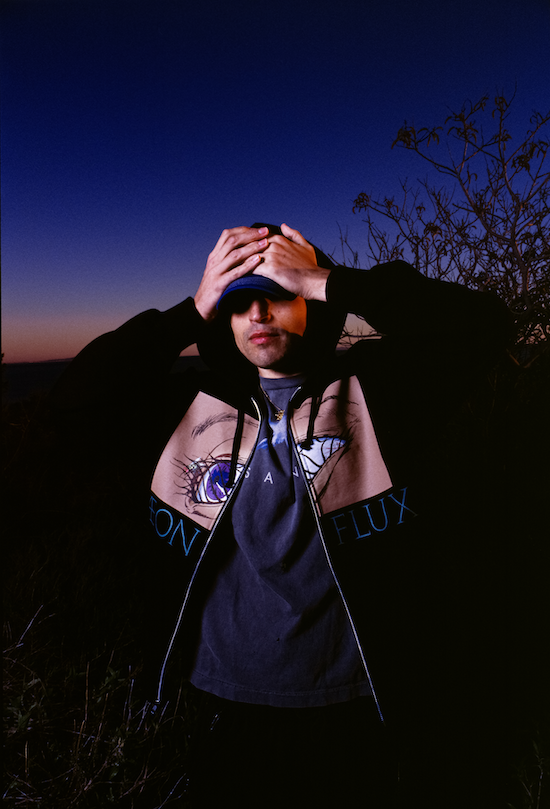

What does this have to do with Joe Thornalley’s music? “There’s a certain identity my music has”, he admits. “I talk about happy melancholy a lot.” He does – the producer known as Vegyn has long since supplied this descriptor himself. And he’s not wrong! The phrase catches the emotional tenor of much of his work, subtly sombre, buoyed by the beat. But there’s something Freudian at play there, too, in the meditative haze that floats atop a Vegyn production, in the snatches of conversation that flit through the mix. That quality is the source of the distinctive vibe he’s captured for Frank Ocean (or Travis Scott cosplaying as Frank Ocean), and it’s out in full force this April on his second official LP, The Road To Hell Is Paved With Good Intentions, a dreamlike melange bubbling up from the subconscious. The ties to the id are right there in the title of the first track: ‘A Dream Goes On Forever’.

Vegyn’s newest release arrives a decade into his career; his CV is established and his place in electronic music lore secured. The son of the guy who produced Pornography for The Cure, Joe Thornalley met James Blake and Frank Ocean at Plastic People, who were impressed by his early beats and put his music on the map. Since then he’s produced for chart-toppers like Scott and auteurs like JPEGMAFIA and Dean Blunt, all while releasing a steady stream of singles and mixtapes. He also runs his own label, PLZ Make It Ruins. But The Road To Hell is his first major solo statement since 2019’s Only Diamonds Cut Diamonds.

Diamonds was an impressive debut, an intricately crafted electronic record layered with crisp beats and surprising turns. But after he crossed the finishing line, Thornalley realised he didn’t care for the working method he’d used to get there. “It was very much orientated around automating things using a computer, it was all software-based,” he said. “I was so bored of operating in that way; I’d just end up tweaking things endlessly.” The album was released in 2019, but by then he was already moving on, trying out a new approach and making music that would make its way onto The Road To Hell.

Thornalley has long been a fan of Catching The Big Fish, a book about transcendental meditation and creativity by David Lynch, the human field day for Freudians. He cites it as an influence on the loosening of his creative process, not forcing himself to make something when the ideas don’t flow. “If I’m not feeling creative, it can just be a day of organizing,” he said. “’Today I’m just gonna do cable management’, or ‘Today I’m going to move this thing around in the rack.’” And when inspiration does strike, he’s careful not to set firm rules about where and how he starts. “I think even by opening up the computer, you’re setting a precedent for what it is you’re doing,” he said. So The Road To Hell had several on-ramps – piano, synth, laptop – but Thornalley tried to arrive at each of them organically. “I try not to set any stern rules for how things come about, or to prioritise digital or analog for the sake of it”, he said.

This process required a greater sense of play, in both senses of the word – a little more fun and literally playing instruments, mainly piano and guitar. He practices both by studying other artists. “A lot of the time I might just sit down and try and learn another song, somebody else’s music,” he said. “I often recommend that to people who are just starting out. I learned a lot by just trying to copy boom bap beats from the 90s.” These days it’s less boom bap, more Bach. “I have to do it by ear. Just sitting there working out that classical stuff is really beautiful. With Bach, just working with two notes at a time, you’re able to convey all this intense feeling. It’s hundreds of years old and it still conjures that human experience.”

If other artists’ music is good for practice, he goes to books and films for inspiration. He especially likes Ursula K. Le Guin, and when he spoke to tQ he had just finished Blood Meridian. “I’m dyslexic as fuck, but Cormac [McCarthy]’s writing just kind of completely makes sense, no punctuation”, he said with a laugh. He rhapsodised over the novel’s famous conclusion (but was emphatic about not giving anything away): “These are all the things I’m interested – all these swathes of colour and grey.” The novelist definitely over-indexes on “melancholy”, less so on “happy”, but it’s still wild to imagine one of his western wastelands soundtracked by Vegyn.

Bach, Le Guin, and everyone in between share one key virtue for Thornalley: decisiveness. “As a producer, as an artist, a composer, a filmmaker, or whatever it is you’re doing, you’re just making choices. It’s a series of decisions that you make that sound a certain way or look a certain way,” he said. “There’s no right or wrong answer to these questions, it’s just a matter of how you choose. I like it when people have a very clear identity in the choices that they making.” He offers up Kevin Shields as a prime example. “I think about My Bloody Valentine a lot – it’s music that I really, really love – it contains the strangest choices of all time. It just doesn’t make any sense!” he said. “Like, okay cool! Another solo, sure!”

For his new album, Thornalley wanted to capture that decisiveness. Citing a quote from French producer SebastiAn – “The brain is the enemy of music” – he made a conscious effort to tamp down the endless tweaking of his earlier work. “If you start second-guessing yourself the whole time, you won’t allow yourself to make any mistakes,” Thornalley says. “And the mistakes – that’s where all the interesting stuff happens.”

So how do you stop second-guessing? For Thornalley, the answer was to work faster. You can see that in the music he has released in between the two albums, most notably his side project Headache, a collaboration with screenwriter Francis Hornsby Clark. The Headache album The Head Hurts But The Heart Knows The Truth flew just below the radar on release last year; the pair made it quickly working side by side in the studio, releasing it just as quickly. Musically the record is firmly a Vegyn composition, but Clark contributed the words with the pair feeding the lyrics into AI over and over in order to generate the perfect tone and cadence for the project: essentially the RP accent of an English man who was the platonic ideal of an imaginary, distinguished British actor.

Thornalley started the project as a lark, “a cute, fun side project made with a close friend.” As the AI intones on one track, “It’s deep, but it’s not that deep.” Intentionally or not, though, Headache tapped into a mainline running through the uncanny valley. By now we’re all accustomed to hearing the voice of a computer, from the creepiness of 2001: A Space Odyssey or OK Computer to Siri’s benign iPhone queries. But the voice on Headache sounds both eerily human and not. When it pleads, “Say I’m normal – please, for fuck’s sake, say I’m normal”, you shudder with faint sympathy. Headache won devoted fans, many of whom took it much more seriously than its creators. A comment on a YouTube video for the album’s final track, ‘The Party That Never Ends’, reads: “Hope this person lived. Lots of pain in this album.”

Projects like Headache hit a nerve as the industry (and the rest of the world) figures out just what to do with artificial intelligence. While the CEO of Universal extols its virtues to the New Yorker, a survey found that 73% of producers worry AI could replace humans behind the board. Thornalley isn’t one of those producers. “Especially with electronic music, technology is always the most interesting thing”, he said. “People get concerned about AI, but people hated drum machines when they first came out. It’s still about the human experience, somebody actually playing a thing.” Digital personas like Headache are an interesting test case, a playful splash in the shallows of a technology that will drag music – how we make it, how we listen to it – into much deeper waters.

AI aside, the speedy workflow that enabled Headache also worked for The Road To Hell. Thornalley had been spending a lot of time in America, putting together some demos and loose ideas for the new record. Upon returning home to London, he had a series of hyper-productive sessions when much of the album came together. “With all these British collaborators I felt considerably more inspired. I suddenly felt more in tune with the overall feeling of the record, and sometimes you have to strike while the iron is hot,” he said. “That’s what I mean about getting out of the way and just letting things happen naturally. When they’re feeling good, just keep going.”

There’s no better example of that method than ‘Another 9 Days’, a collaboration with songwriter Ethan P. Flynn and one of the album’s standout tracks. Thornalley used to bristle at sharing work in progress. (“Maybe I’m a bit traumatized because I remember early on, people would always be like, ‘Bro, no one wants to hear your stinky beats!’” he admits.) But one day Flynn and Thornalley got together to just mess around. The singer suggested listening to unreleased Vegyn work, and was quickly drawn to the bones of the particular track. “Then that song was done in like two minutes,” said Thornalley. “That’s when stuff is really pure and you don’t have to get in the way of it.” ‘Another 9 Days’ is a deceptively simple track with a powerful, longing chorus – a reflection of Thornalley’s deepened interest in traditional song structure.

Not everything came so easy. Thornalley laboured for an especially long time over ‘Last Night I Dreamt I Was Alone’, a woozy instrumental that feels like a clear bridge between Only Diamonds and The Road To Hell. Despite his plans to resist revision, Thornalley indulged in a fair amount of trial and error with the track, shortening and lengthening it over the years. He finally knew he was onto something when he played it for a friend who commented, “This doesn’t sound like you at all.” It opens with a faint crackle then gives way to cascading synths before fading out into a gentle piano motif. One lonely dream.

The music that ultimately made it onto The Road To Hell was composed between 2019 and 2023 – much of in 2021 after that productive return to the UK – but it’s the oldest songs on the record that contain its core DNA, songs like ‘Last Night I Dreamt I Was Alone’ or ‘Trust’, the first piece he worked on. The id looms large in both: in the title of the former and the sound of the latter. ‘Trust’ is filled with echoes and distant voices, centred on a few simple bars of piano and singer Matt Maltese’s plaintive voice. Both reflect that Vegyn sound, an irresistible melody or riff ensconced in a sonic fog, something indeterminate yet familiar.

For Thornalley, that dreamy sense of distant familiarity is what art is all about. “Looking at a piece of work in a gallery or a museum, or having something conveyed to you, even like Neolithic cave paintings, it’s like, they’re still the same people,” he said. “They’re still the same things going on, we just also have to deal with, you know, the internet.” Whether it’s the internet or AI, we’re all still processing the uncanniness of the everyday. Thornalley pulls that process up from the murkiness of our brains and sets it to a beat.

The Road To Hell Is Paved With Good Intentions is out on 5 April