All exhibition pictures by Maria Jefferis/shot2bits.net

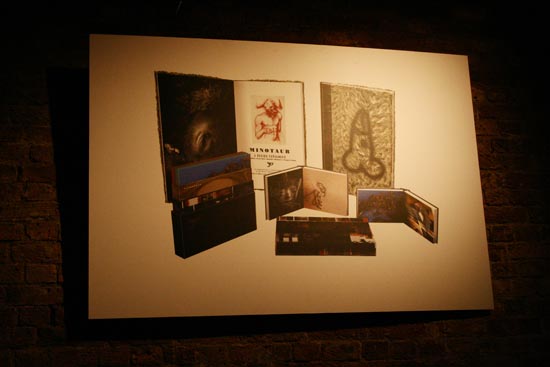

Let’s get the facts and figures out of the way first. Minotaur is a Pixies box set of sorts. It does contain all five of their albums on vinyl and CD, DVDs, a hardback book of new art prints, framable high-quality prints, posters and blu-ray discs, all in an austere box that would easily house the screaming baby that adorns the front of the Gigantic EP.

Can you afford to buy this? It’s about £400. Shit, I can’t afford to buy it and I wrote the introduction to the beautiful (fake) fur lined book that comes with it. Maybe if I get hit by a bus and some insurance comes in . . .

The thing is, it’s not really a music collectible but rather a graphic art collectible. It’s an awesome thing. If I could afford it I’d buy one. And while all of the new photographs and illustrations certainly feel more like art to me than a Hirst spin painting or an Emin lithograph, I’ll leave the art crit to the art critics and the lecturing on consumerism to the Marxists.

All of the above is only important to me as it has given me a chance to meet the visual genius behind the Pixies, the Cocteau Twins, Ultra Vivid Scene, The Breeders and most of the 4AD stable to date, Vaughan Oliver. (He, along with original Pixies photographer Simon Larbalastier and Artists In Residence honcho Jeff Anderson, is responsible for the Minotaur package.)

At home in Epsom he strides round a book-and-CD-lined office. There is a large glass of wine in his hand that, at all times, looks as if it is about to disengorge itself all over the room. But it never does. He is refreshingly idiosyncratic (his first action is to soundly bollock the interlocutor for taking sugar in his coffee: “You HAVE to cut it out John!”). And then once again for mistaking him for a Geordie. He comes from Sunderland! He has a flush to his cheek and a twinkle in his eye, which make him both very avuncular and slightly diabolical. When his blond-haired son walks into the office he barks: “BECKETT! Say hello to John!” And then starts summoning up cash from around the room for his son’s five-a-side match, while addressing me: “After Samuel, you see? He was either going to be called Beckett or Pele! Ha ha ha!” Then to his son: “Those were your first words weren’t they Beckett? ‘I am un chien Andalusia! Ha ha ha!” On cue Beckett gets embarrassed and protests: “D-a-a-d!” before leaving for footie.

His eagerness to be a good host borders, once or twice, on paranoia. Despite knowing me to be a Pixies die-hard, he asks me if I’m bored about hearing about the stories behind the albums and worries that his answers aren’t exciting enough (when, to me they’re gold dust). And due to both of us being mildly deaf, the conversation keeps descending into the kind of farcical exchange that used to form the backbone of jokes printed on the rear of England’s Glory matchboxes.

While he’s no shrinking violet and seems quite at ease with his place in the world of alternative music and design, he obviously sees himself as a collaborator or even a cog in a bigger machine. Even though I spend the afternoon making him talk about himself he very rarely says ‘I’; instead he says ‘we’. And the ‘we’ always means something different. It means Ivo Watts-Russell and I, 4AD and I, the Pixies and I, Simon Larbalestier and I, the creative arts students of Epsom University and I . . .

Talk, as is often the case with Northern chaps living down South, turns to where our families hail from and it’s not long before we’re chunnering on about Ireland and how the interviewer, in relative terms, loves Wexford and hates Dublin.

Vaughan Oliver: “I like Wexford. I did a job with a band called 10-Speed Racer. Terrible name. Great band. We did some good stuff together. It created a fuss because of the nudity. The local and national papers – The Sun – were concerned. I’ve always struggled with that. In terms of rock & roll and breaking boundaries and being outside of the mark in terms of visual, I’ve never really been able to do something as extreme as the discipline should have allowed.

“I.e. with Surfer Rosa, it had to have the nipples stickered when it went to the States. In terms of the visuals I’ve never been able to do something as extreme as what the music does. It seems to me to be a kind of censorship. So we’ve never really been able to do what we wanted to do.”

I remember being mildly shocked when I saw that cover for the first time. I guess I was a callow youth – and an altar boy at that – but it was at the height of political correctness and it was an unusual sight. Even though, obviously it wasn’t like a Scorpions or even a Bon Jovi sleeve. Did you get criticized for that cover?

VO: "In terms of feedback, no but it was stickered. I didn’t think twice about it. You’re not wanting to shock but you are wanting to grab people’s attention. The Spanish theme came from Charles [Frank Black]’s lyrics. So I thought ‘Flamenco’. These were the most traditional images you can get from Spain. The idea was to subvert it. To get her to do it topless. It seemed like a straightforward idea to be honest."

*It’s quite sexual but not sexy, if you’ll accept my distinction.**

VO: [nods]

*You could say that about The Pixies themselves. They were torrid but you don’t really think of them as being a sexy band. They were, as you’d say, hot under the collar. And that’s everything about them. The noise they made as much as anything else.**

VO: "Yeah, they were very animalistic."

You mentioned briefly about how you met Ivo Watts-Russell and first got involved with 4AD . . .

VO: "It was 1980. I came down to London in pursuit of a career as an illustrator. I side stepped into a graphic design studio. There were two guys in the studio and they’d helped establish the name of 4AD and worked on the first few sleeves. Then they weren’t available to do the next few so they said to me ‘Go and meet Ivo.’ After that I used to bump into him at gigs. Pere Ubu. Rip, Rig & Panic. I ended up saying to him that he needed some consistency, a logo, label designs and he said ‘Fabulous.’ He at that time, and for a long time afterwards, was truly philanthropic. He just wanted to put out music that he liked. He wanted other people to share in this. He had no commercial aspirations if you like. He just wanted to put stuff out and to put it out in a nice sleeve, that people would want. He had really old fashioned ethics about care and quality and stuff like that. It was about three years before he got a studio that he invited me in to and said ‘Work with me.’ And I was his first employee. And I think he expected me to do more than just sleeves so there was warehouse work and stuff like that and we went from there really.

“He was feeding me stuff like the Birthday Party and The Cocteau Twins. I guess we shared a natural interest in the same area of music, so it wasn’t like working for a record company because everything that he fed me, I was inspired by. You can’t want more than that can you? He didn’t tell people that they had to work with me, he just said they could if they wanted. So it wasn’t like we set out to establish a label identity, that just happened with time. It evolved organically. But I guess because most of the sleeves came from me, there is a thread there. The idea was always to focus on the music, read the lyrics, talk to the band.

“In those days, I’d hear the demos, go down to the studio when they were recording, and I still do that now if there’s time. I’d have about three months to think about stuff – while I was working on other projects. When I talked to contemporaries working in record sleeve design, they’d say ‘You lucky bastard. We get the call on a Friday afternoon and we have to have the sleeve finished by Monday morning. How can we hope to get inside the music?’ I didn’t take it for granted but that was the situation.

“We had the creative freedom. Remember back in 1980, he [Watts] didn’t do contracts. If the band were happy, they’d come back to do the next album. He didn’t tie anyone in. That was the independent way. I think it was the same at Rough Trade and the same at Factory.”

You’ve already talked about values like care and paying attention to lyrics and stuff like that but above and beyond this, did you have a philosophy that you followed as regards artwork?

VO: "I guess our philosophy has always been to reflect the music, to try to create . . . to try to get into the atmosphere or mood of the music. The art should be an indication of what the music is about. At the same time, you’re not trying to define the music, you’re trying to make a suggestion about it so anyone else coming to it can make their own mind up about it. And how you do that – or how we’ve done it at least – is to be ambiguous. To create an air of mystery about it. There has to be enough there to pull you in. To pull you in across a room, I think. For it to be worthwhile when you get it in your hands. And then, really, you have to be able to come back to it time and time again. I suppose that’s why we employ the idea of ambiguity and mystery. I suppose in terms of time, that’s been rewarded when we’ve had exhibitions and people from all over the world have said ‘Is this about this or is it about that?’ And they talk about stuff that I’ve never seen in it. They talk about other stuff. And I think that’s what a good sleeve should do, to leave room for a personal interpretation and still have an immediate impact. Do you know what I mean? Not wilfully abstract and to still have a connection to the music. [Peter] Saville at Factory, for example, is the antithesis of what we do. His sleeves have nothing to do with the music. He’s doing something that’s about him and about popular culture at the time. But it’s not about the music and I think that if you do the package for anything, it should connect to the content. Then it has substance. And I’d love to think our stuff has substance. That would give it a longevity."

Talking about this duality – this room for the viewer’s interpretation while having a concrete connection to the music; which sleeves like this did you obsess over when you were young?

VO: "When I was a teenager, what got me into it was Roger Dean and his stuff for Yes. That was about freeing the imagination. The last thing I wanted to see was a picture of the band. I’m not interested in that! With 4AD, all of the bands were more interested in an interpretation of the music. They all said: ‘Our personalities are there. You don’t need to do grinning face packs or head shots of us.’”

Prior to the Pixies, which was the band that you enjoyed working with the most?

VO: "Prior to the Pixies? I suppose the big band was the Cocteau Twins. And you use the word ‘enjoy’ . . . It was a, er, it was, ah, trials and tribulations with them to be honest."

I’m aware of their reputation and I’ve met Robin.

VO: "They were really fucking hard work to be honest. There’s an interesting comparison there. Because for the first few years they were the main band and working with them and the inspiration they gave me was amazing. But all they could do in terms of responding to the images we gave them was to be negative. “Our music’s not about this. Our music’s not about that.” But they could never be [positive]. It was hard work. They’re famous for their reluctance in interviews and doing gigs. But it was not like that with the Pixies. They’re great in conversation. They toured the world. They were the antithesis. But that’s not to measure one against the other because they were both creative experiences."

When did you first encounter the Pixies and what were your initial thoughts on them?

VO: "Ivo played me their demo tape. It didn’t really click with me. Then I was going to New York and Ivo said ‘I’m thinking about signing them; go and see them play.’ I think it was at the Rhode Island School of Design. I went to see them and they were . . . amazing. I hadn’t really got it from the demo tapes. Again, I had to show respect for Ivo’s ear. I wouldn’t have signed the Pixies. But then I got to see them and it was amazing. When I got back I said ‘Yes. Amazing. Lovely people.’ But I don’t want to overstate my role in them getting signed at all. All the bands were signed by Ivo."

I love the sleeve to Come On Pilgrim . . .

VO: "Well, the brief was very specific. When I spoke to Charles I said I would work round the music. He mentioned the David Lynch stuff and I got into that straight away. We shared an influence of inspiration there. “Male nudity. That’s what I like. And David Lynch. That’s what I like.” GREAT! I’m into that as well! So I went to a Royal College Of Art show and Simon Larbalestier was showing there. He’d shown me his stuff two years previously and I knew he would be good for a band at some point in the future. And there on the wall, already, was the guy with the hairy back. Simon, in terms of his personal aesthetic, has always seemed to be perfect for working with the Pixies."

Who is the hirsute chap on the cover?

VO: "I can’t remember his name. He did contact us a few years ago because his son had grown up and got into the Pixies. He said ‘Please. Can you let my son know and can I have a print?’ It was a lad who was at college with Simon. The hair wasn’t as strong as that, it was lighting but what was fabulous was that he was going bald but had this growth everywhere else. I don’t know if he had it behind his knees but he had it everywhere else. We should do a revisit. Repose some of them. It wouldn’t be very nice to see the Surfer Rosa lady now after all those years would it? Gravity may have taken its toll."

I think the Pilgrim guy might be worse to be honest. When I saw the Pixies last Charles didn’t miss the opportunity to cheekily suggest that the hairy guy was you.

VO: "Hmmmm. Well, there’s the baby as well. Where’s he now?"

It’s a good point. The young lad who was on the cover of Nevermind has achieved a certain amount of micro-fame himself. I think my favourite of all the covers is actually the 12” of ‘Here Comes Your Man’, I think because for the first time ever I fancied owning a dog after seeing that. It’s such a handsome dog.

VO: "Isn’t it funny? I think it’s funny the effect that that piece of music and music packaging can have on anyone in their formative years. I get loads of feedback on this. It’s about the music. The music gets straight in there. But accompanied by a simple image and it hits so many people in their formative years."

You think it’s funny?

VO: "Yeah, I think it’s funny because it’s gone now. In the age of the downsize, it has gone."

Download?

VO: "Yeah, the download. Thank you. The disappearance of the packaging. You’re talking about a bit of cardboard surrounding a bit of vinyl and that made you think about owning a dog! How fabulous is that?!"

I see what you’re saying. I guess no amount of downloads is going to affect your attitude towards animal possession, one way or the other.

VO: "Or possession. Or possession. Possession of the music, that is."

It’s not that clear cut though is it. Sales of CDs are down massively and downloads illegal or legal are up by loads but vinyl appears to be fighting something of a rearguard action. If you look at a label like Southern Lord, they do, what I presume is a decent trade in vinyl not just because of the music but because the packaging is so exquisite. And even though Southern Lord is ostensibly a cult metal label, I think there is a link between the Southern Lord visual aesthetic and that of 4AD . . . Talking of stuff being funny though, I think it was about two weeks after buying it that I got the joke on the rear cover of the Gigantic EP. Were there any other visual gags?

VO: "The big glove? I don’t think so. At least that was the most obvious joke. The front came from seeing them at a gig. Charles. A big baby having a primal scream. I came away from a gig with the idea of a screaming baby. We repeated an image with the single ‘Monkey’s Gone To Heaven’ and on the album Doolittle. So there was a challenge. How do you repeat yourself and make it interesting? There’s a grid on there in front of the monkey. I spoke to Charles and he professed to me: ‘A good pop song is purely formulaic. It’s purely a matter of mathematics.’ And I didn’t get it. I was disappointed even because I thought that music comes from the heart. But then I thought that in painting there is this thing known as the golden section, so that’s why that grid is there as a reference to formula.

“After that it was Bossanova and four albums in and I’m in the world of the Pixies and I’d already had a dream about a globe. And then when I heard the album there were a lot of references to UFOs and going into space. There was one specific song ‘Velouria’; and she had been pulled out from this place called Lemuria. Lemuria was a hidden continent, or lost land, which was like but not the same as Atlantis. I don’t know if you ever noticed this but on the globe, off the coast of America, there is Australia, and a reference to Lemuria. Trompe Le Monde was about the cow. It was in the age of mad cow disease. The bull’s eyes. Work for the butcher. And that was also a reference to trompe l’oeil."

I was going to ask you about the booklet that came with the initial run of Doolittle. As I remember, every other song on the album had a visual representation. Was this a reflection of how big the band had become?

VO: "Not really. I wanted to do this with every band. To represent every song. It seemed like the obvious route to me. I pitched the idea to Ivo and he said ‘It’s a great idea, go for it.’ We did the first 30,000. We did something similar with Bossanova. The songs are replete with imagery. I liked what you said about The Pixies, about how they used the language of violence. But it is the suggestion of violence or the immediate aftermath of violence so the images themselves are not violent but they do suggest violence. Do you agree?"

That makes sense. If you take the screaming baby for example, it suggests the pain of childbirth without displaying it. And the same with all that butchered meat. Do you always work with Simon?

VO: "Only on the Pixies. When this project [Minotaur] came up, I guess I could have worked with another photographer but I wanted to work with him. I hadn’t seen him for eight years and he was living in Bangkok. Both of us had been listening to the Pixies for twenty odd years. I said to him how did he feel about revisiting the Pixies and he said he was afraid because the sleeves had become iconic. But in the scheme of things, I said what about throwing everything out and starting again with our current mentality and our current vision and our current response to it. The idea of putting all those five sleeves into a package and making it work, seemed a bit rude to me. It didn’t feel like it would work. It was about us addressing it twenty years later."

Where did the idea come from originally? Was it your idea?

VO: "The original idea came from A + R. Artists In Residence. So it’s not 4AD. It’s not Beggars. A + R, Jeff Anderson had done stuff with NIN and Sigur Ros. He was this guy out there doing proper packages. To my mind. I’d seen them and I thought ‘He’s alright.’ He went to 4AD and said ‘Can I license the stuff?’ He came to me and said that I’d like to do this in a really nice way, with a new perspective on it. Do you think it’s a good idea?"

Yeah, I think it’s a good idea. Going back to 2004, I think what I was most concerned about was whether the Pixies would do new music or not. Thinking about this, I can’t think of any good reason why there shouldn’t be more good art in the world. Why, have people voiced doubts?

VO: "People have voiced doubts have they?"

No. I’m asking you, have the voiced doubts.

VO: "But have people voiced doubts?"

Not to me. I guess the only thing that would bother me is the price. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not making a value judgement about what art prints cost. I think, seeing what I’ve seen, I can say that I definitely think it’s ‘worth it’ but it’s just a matter – as always – of whether people can actually afford it or not. But I need to be clear about saying, people’s ability to afford it has nothing to do with whether it should be done or not.

VO: "Exactly. You don’t paint a painting, worrying about the price. I think the people who are moaning about it John – it’s probably not aimed at them. I didn’t really stop to consider this stuff until after it was done. And then I read on the blogs that there was to be no new music. Well, that’s a Pixies issue. With respect to 4AD and the Pixies, they haven’t just stuck in an extra couple of tracks so the real hardcore aficionados will be required to buy it. They’re not sticking a couple of tracks in there, which would oblige the fan to buy it. If you’ve got all the music, already in great packaging then I’d leave it there. It’s not aimed at you fellows. It’s more aimed at a collector’s niche market and it shouldn’t upset you fellows. The issue of the Pixies doing new music is a totally different issue. In the context of limited edition art prints I don’t think it’s that expensive. But really it’s a benchmark, as no one has done anything like this before."

*The author would like to apologize for the repetitive and brutal use of the word ‘sexy’.

For more details on the Minotaur box set visit the 4AD website.