The clang of the Yankee Reaper, on Salisbury Plain!

A music grander – deeper – than many a nobler strain.

Will Carleton, great-uncle of Van Dyke Parks, 1873

Gone, just like I said

The good old days are dead

Better get it through your head

As you harken to the clang of the Yankee reaper

Van Dyke Parks, great-nephew of Will Carleton, 1975

"You ever been to California, Taylor?"

Yes, once.

"Where did you go?"

Los Angeles, for two days. Looked at a concrete shopping mall on Beverly Boulevard and sat in a tour bus.

"Well… it takes some time. It doesn’t reveal itself immediately…"

Songs Cycled, the new album by Van Dyke Parks, is playing on my headphones; I’m standing somewhere in EC3 with the church of St Botolph Without Aldgate here and the Gherkin there, looking for the right road, while around me London – as usual – is trying to exist in forty or fifty separate periods of history at once, and almost succeeding… and simultaneously I’m being flung between ten or eleven decades of American song by this warping, shifting music, in the closest thing London can manage to a Californian spring.

Ten minutes or ninety-nine years later – I honestly couldn’t tell you – I arrive at Van Dyke Parks’ hotel, but either I’m early or he’s late, so I deflate on a battered red leather sofa in the lobby and sit there listening to lunchtime. Playing quietly in here: Billie Holiday’s version of ‘East Of The Sun (And West Of The Moon)’. Then, from the adjoining room, a Little Mix track pours through the wall like next door’s unhappy lovemaking and there’s a muted trumpet here and ProTools there, and it’s back and forth again, as it can be, from time to time…

Give me a moment, or two.

I first heard the work of Van Dyke Parks in the same place most people first heard the work of Van Dyke Parks: The Beach Boys’ ‘Heroes And Villains’, for which he wrote those tumbling, tantalising lyrics about sunny down snuff and dancing the Cotillion and what a dude’ll do, and then the second, third and fourth places were bootleg recordings of Smile, the young Brian Wilson’s abandoned masterwork, for which he wrote a whole lot more. A couple of years later (or maybe a decade?) I began to discover Parks’ own records, a beautifully baffling body of work, a rapid-cycling, semi-coherent compendium of American music from Sousa to psychedelia, within which the laws of pop and rock and time do not apply.

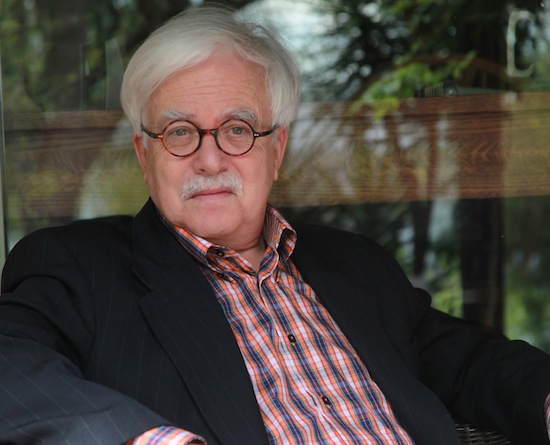

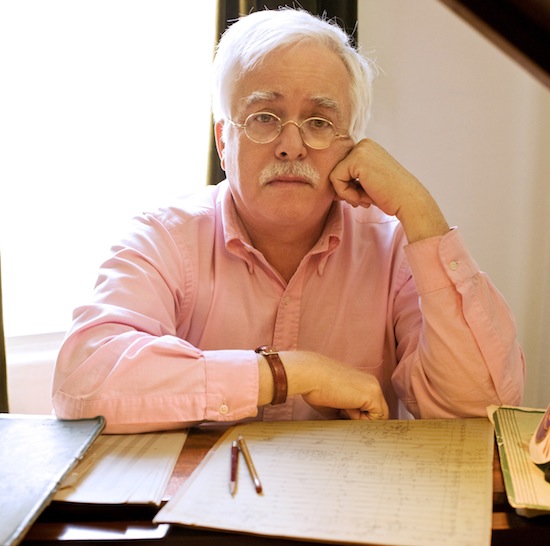

Van Dyke Parks, I would maintain, is one of the all-time greats of semi-popular music, and when he arrives snowy-haired and twinkling he’s politeness personified, shaking hands and apologising profusely for being just a little heavy-lidded: "We partied last night. I was overserved, which I thought was very rude of them, but you can’t get good help these days…"

The hotel has a pub attached – it’s lunchtime, it’s empty, but we walk to a table in a distant corner, clear of the loudspeakers. The pub is done out in dark wood and bottle green and as much shiny brass as possible, with fruit-sweet-coloured paintings of Old London Town hung up on the walls between mock-antique lamps and the usual tat; it’s staffed by unmistakably modern young men in all-black outfits they’ve been told to wear, chins on their hands, elbows on the bar, gazing at the big TV screen on the back wall and waiting for half-time results or something (anything), smelling the hops and the 12 o’clock kitchen. One of them walks out to greet Van Dyke and I, and is visibly startled to be addressed as "dear heart" by this uncommonly delicate American in candy-striped shirt, knitted tie, blue jeans and leather slip-ons; the lad glances round at me in hope of a rolled eye or something (anything) but gets nothing of the kind, because this is Van Dyke Parks, one of the all time greats of semi-popular music, and he wants some vegetable soup. Once this has been established, I can switch on the recording machine. The two of us settle down in a sunbeam and Van Dyke talks a mule in half.

He doesn’t always answer a question directly, often preferring to sidle up on its blind side, and from time to time his gently meandering stream of consciousness will disappear into the bushes, reappearing where you least expect it. But he’s excellent company, and time passes quickly, and this is how it goes.

Van Dyke Parks’ arrangement of ‘Heroes And Villains’, performed with Clare & The Reasons, 2010

So – I say – as far as I’m concerned this new album, Songs Cycled, is the sharpest and most enjoyable Van Dyke Parks has made since his very first, Song Cycle, from 1968. The similarity between those titles is quite intentional, obviously. This new record may be less reckless and a lot less extreme than that record (rumoured to be, for a number of years, not just the most expensively-made but the worst-selling album in the Warners catalogue) but there’s a comparable freedom to it, the curious arrangements, the illogical architecture. Certainly, the two albums have more in common with each other than they do with anything in between.

(What came in between? It ranged from cokey-but-captivating fusions of Tin Pan Alley and calypso music (Discover America) to children’s songs about Brer Rabbit (Jump!), a Japanese-American fantasia (Tokyo Rose) and a rather more low-key collaboration with Brian Wilson (Orange Crate Art), as well as a ton of production and soundtrack work which ran the gamut from The Jungle Book to Robin Williams megaflop Popeye. At its best it was marvellous; at its worst it was at least unique.)

But this is the stuff – the stuff that only Van Dyke Parks can do. What put him back on this particular road?

"I don’t work to a plan. I don’t have a five year plan, I don’t have a five minute plan – a three minute egg is about the limit of my powers of prediction. So I don’t predict my way through an album, but I got to a point in this record where I just felt things were entirely too normal, and I decided to make a defiant gesture… and that defiance, that sonic defiance is in ‘Sassafrass’, which is a perfectly beautiful Appalachian tune written by the big rabbi of Celtic tradition in the mountains, Billy Edd Wheeler, who’d written ‘The Rev. Mr Black’ and a lot of other beautiful but incredibly normal songs.

"And ‘Sassafrass’ is a normal song. I’d first heard it with the Modern Folk Quartet. But I was aware of Billy Edd because Billy Edd comes from Swannanoa, North Carolina, a bosky dell near the mountain where my parents built their cabin in 1953, and where my wife and I got married, ultimately. And Billy Edd became a friend, this poet laureate of Appalachian culture – a culture that was protected entirely, before the age of satellite dishes, when there were innumerable bluegrass or old-time music radio stations, uncontaminated by mass media and its dictates – and to bring that man, an octogenarian, into our time, and to make sure that he knew how relevant he was to my life, I recorded ‘Sassafrass’. But I couldn’t do ‘Sassafrass’ in a normal way. I had to fuck it up royally. All the while I had at my shoulder the ghost of Spike Jones; I tried to make it an audio entertainment, a trip for the ear. And in that I came as close as I could to Song Cycle, the original album."

Still such a mesmerising record, a puzzle picture…

"…with powers of deception that most people have not forgiven yet! But I’ve always thought that deception was very important, an important tool in the arts. That kind of deception I hear in Schubert or other fine songwriters of the 19th century, who take you to the edge of a cliff and drop you. To me, ‘Sassafrass’ has that kind of motivation."

I tell him that the first time I heard it I laughed out loud, and Van Dyke beams and offers his hand for another shake.

"I want to thank you for that! Because that’s what we’re here for, to entertain! Yeah – so you were laughin’!"

Years ago, a musician friend and I were listening to ‘Donovan’s Colours’ from Song Cycle – in a mildly altered state, I confess – and we ended up on the floor in hysterics. Just at the sheer audacity of it, all those right-angle turns…

He smiles again. "That was so much fun. There was no evil intention in any of it – I have no malice, I can’t admit to any malice. I have too much else to do. I love the beauty in universal harmony, I love resolution, confirmation, so much that it’s almost like I’m turning to deception in the music to add a surface tension to that contentment that I actually want to express."

Feature continues below image

You’ve spoken many times about your love for Spike Jones…

"Yeah, ear candy is where I came from. Stereo!The first Spike Jones tune I remember hearing is in 1948, I would have been five, and I heard ‘Cocktails For Two’, with that melodic percussion dominating… I remember when ‘living stereo’ came along, the sweep of the train from the left speaker to the right. All of those things were my poison. They’re what I wanted to kill me."

I suppose I belong to the last generation of British people for whom old-timey American music feels extremely familiar – part of my cultural heritage too, albeit once or twice removed. When I was a toddler my mother would sing me songs from wartime. When I was a child the BBC would pad out its schedules with silver-screen Hollywood movies and silent comedies; you could watch Harold Lloyd shorts every night, and plenty of us did. The sighing, slipping-and-sliding sound of this music has a similar effect on me, perhaps, as it has on older Americans – mingled comfort and terror: nostalgia. But I’ve no idea what younger people think when they hear it, stripped of context. With its unfamiliar intervals and strangely creepy jollity, it must sound like music from another dimension.

"I think so," nods Van Dyke. "My wife Sally and me, at one time we knew a nonagenarian. He would need a ride home from church and we would give him that ride. The guy was in his nineties, he was a veteran of World War One, he had breathed mustard gas – he had met somebody who shook hands with Napoleon! I mean, ancient history? But ancient history means Elvis the Younger for a lot of kids today. So I think it’s hard to explain origin… but that’s what we’re here for. I mean, you look at the cover of this album…"

Van Dyke reaches into his bag and pulls out a vinyl copy of Songs Cycled, with its strange oil painting of a cheesecakey bicycle rider at the beach, chopped off at the neck to preserve some fundamental anonymity, done in the rich, toasted-tobacco tones of radio days.

"It draws one to the images of Southern California, the Good Life. It’s trying to capture a world that we have just left behind, that we are a handshake away from. What I have in my work, as we see in the parallel universe of this visual art, is a tendency to try to capture cliché and make it an artform. I seek that, I take images that pre-exist, reiterate things I’ve heard and bring them forward. I want to keep that in my work, that retrospective quality, to find out where we’ve been and what we’ve done.

"In a way this is not creative work, but it takes an ability to react and to re-present what we have known, and what should be confirmed and vomited into the future. I want to preserve what is beautiful, and deserves this migration to another generation, perhaps without explanation, but which invites exploration…"

Van Dyke Parks on Song Cycle from Richard Parks on Vimeo.

Van Dyke Parks on Song Cycle

The first place I saw Van Dyke Parks being interviewed was on a chewed-up videotape of a Beach Boys documentary called “An American Band”. He was wearing a wide-brimmed hat, a blue singlet and a bushy black moustache, standing on Sunset Boulevard in the flat and polluted late-Seventies sunshine looking like Cheech, or maybe Chong, and arguing that “columnated ruins domino” was surely no more incomprehensible than “ding woody pearl hang ten” or whatever it was the Beach Boys used to sing, and claiming to have told Mike Love – the moaniest, bitchiest and most aggressively dumb of the BB clan, who’d been hustling for VDP’s removal from the project since he walked through the door – that all those tricksy, kaleidoscopic lyrics he’d provided for Smile “aren’t important. Throw ’em away! So they did.”

Prior to Smile, Van Dyke had been around a bit. A successful child actor, he’d been a regular in various American sitcoms, even bagging a role in Grace Kelly’s penultimate movie The Swan. He’d written ‘High Coin’, a popular song recorded by Harpers Bizarre, Jackie De Shannon, The Charlatans, Bobby Vee, Skip Battin and The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band; probably others besides. He’d played keyboards on ‘5D’ by The Byrds, released a couple of singles of his own (including ‘Number Nine’, a poptastic version of the Ode To Joy from Beethoven’s 9th) and begun to establish himself as the furthest-out arranger on the West Coast – as illustrated by the better half of Arrangements, a recent compilation.

But Smile was something else again, different to (and better than) anything he or anyone else had ever previously attempted. Everyone knows the story, surely: Brian Wilson, who’d lately found himself writing the most dazzlingly sophisticated and painfully beautiful pop songs of his or any other generation, noticed his friend Van Dyke was “good with words” and invited him to contribute lyrics to the forthcoming Beach Boys album, planned as “a teenage symphony to God”. Together, they went further than either had ever expected – so far, in fact, that the work could not be contained, and for various, uniformly unhappy reasons everything fell to pieces with the album something like three-quarters done. So it has remained: the recreation staged by Brian and the Wondermints in 2004 is a very enjoyable facsimile, but if you want to hear the real Smile, with its real joy and real terror, you have to go back to those original sessions, finally released as a box set a couple of years ago, and use your imagination (the mock-up of the finished album is awkwardly sequenced and probably not much like what would have emerged back then, in a fractionally better world).

Like most of the best and worst music coming out of California in the mid-1960s, Smile was, at least in part, a product of the LSD experience, but rather than looking forward to some vanishingly unlikely utopia – or off into random space – the glassy-eyed gaze was here turned back towards that ghostly old America from which most young rock bands were running, like the wind. Picket fences, innocent girls, Indian war whoops and barbershop quartets, three piece suits in 100-degree heat, the lone harmonium playing in a remote white church… the fear of God. This was the beginning of the great “American Gothic trip”, a preoccupation with American history and folklore which has, in one way or another, informed Van Dyke’s whole career. Was this always a personal obsession, or was it first suggested by the Beach Boys aesthetic, such as it was in 1966?

“Well, I had no ideas!” laughs Van Dyke. “Only the idea ‘write what you know.’ Literature 101. And I didn’t know anything much about the world of Brian Wilson. It was a different world: I was poor, he was rich, he was famous, I had less signature power than Kilroy. But I could write about what had happened to me – that is, I came west to Hollywood. And something I found a most thrilling topic for exploration was how ‘we’ got ‘here’… I wanted to try to figure that out. And to celebrate The American Century…

“I remember when those billboards went up, saying ‘THE BEATLES IS COMING’ – that was Derek Taylor (legendary Beatles publicist who later moved to Los Angeles), he did this ad campaign for The Beatles when they came to America, which was brilliant. It was a take off of ‘The Camels Are Coming’, an R.J. Reynolds ad about cigarette smoking which was real popular in World War One. So The Beatles came, the English groups, British musical entertainment… and this was the first hint that while we slept, the British had fallen in love with our culture, and they were making something of it that we were not making.

“But this was, to me, invasion! A frightening event, like the Japanese had bought Rockefeller Center – which they eventually did, in fact – or some totem of American historic or cultural importance. And what did Americans do as a result? They all adopted British accents! They all got as transatlantic as possible. Things got bett-ah and bett-ah. Nobody wanted to have anything to do with America; America was dropping bombs on Asia.

“So I decided – and it was a conscious decision – to write something examining American culture and American history. I wanted that quality to be in the work. I thought, if we keep that as a sub-topic for the work we’ll come up with something very good, we’ll have a unified feel. And it was one thing I did share with Brian Wilson: he knew low church hymns, I knew low church hymns. He knew barbershop, I knew barbershop. We had a lot in common that had nothing to do with what ‘should’ be on a pop record, which I didn’t know anyway. Nor did I know what ‘should’ be in a lyric.”

Just to be on the safe side, then, he opted for chains of convoluted puns, obscure allusions to a consciously idealised past, torrents of impressionistic imagery, here and there resolving into what seemed like snapshots from a lucid dream (“I want to watch you windblown, facing / Waves of wheat for your embracing…“). My favourite story – possibly apocryphal, like most of the good ones – has Wilson and Parks locked into an ultimately fruitless attempt to somehow capture in words and music a scene of 19th century railroad workers on the Union Pacific, all dusty overalls and blackened faces, arranging themselves for a group photograph somewhere near Promontory Summit. We peer through the viewfinder and suddenly, click! – the shutter opens, the picture freezes and everything turns sepia. This, in the end, proved somewhat overambitious, so instead we got the final section of ‘Cabin Essence’, one of the most beautiful and deeply evocative pieces of music we’re ever likely to hear; the next best thing.

But of course, to the philistine eye this kind of blazing creativity looked a lot like a couple of guys getting much too stoned in the afternoon, hammering a piano in a sandpit full of dog shit, reeling off gibberish, fucking with the formula.

Van Dyke grimaces: “I don’t hold with the idea that there was a problem with the lyrics, as Mike Love did at the time, about ‘over and over, the crow cries uncover the cornfield‘. I think I did a damn good job creating a highly decorative lyrical accompaniment to some really beautiful melodic patterns. I don’t think the crows created a problem at all. I think the music created the problem for Mike, and it was perfectly understandable that he was terribly jealous of me, as it became evident that he wanted my job. And I did not want a job that somebody else wanted. And with that, and with the famous – we can say infamous – stories about Brian Wilson’s psychological collapse, and his buffoonery… I walked away from the job. I got out of there. And it was left undone.”

Bootleg recordings would, in time, leak out to a drooling world – where they would soundtrack countless dog day smoke-ups, night trips, nervous breakdowns…

“I do get an idea that a lot of people sensed how troubled Brian Wilson was when they heard it, and…”

The table rattles. Van Dyke’s mobile is ringing. “I can’t answer that,” he snaps. “That’s Penelope Tree, I betcha.” He picks it up, stabs a few buttons and lays it down flat.

“…I understand that a lot of people listened to bootleg versions of Smile who were in some state of psychological collapse, or crises of personality for one reason or another. Drugs, or just life itself and all the disappointments that people can offer, and they sure are built to disappoint. But a lot of those people heard that music and were sustained by it, and I think the reason for that is that they sensed that the work, basically, is wobbling between absolute despair and complete conviction. And this wobbling is a great component of magnetic art. It didn’t trouble me to see that in Brian, because it’s what made Van Gogh go! It’s what made Vincent what he was! You sense this terrible schizophrenic atmosphere, but ultimately it confirms and celebrates all the potential of the human spirit.”

There’s plenty of humour in Smile (albeit queasy at times) and a great deal of play, but also an unmistakable sincerity. By contrast, when British groups delve into the history of British popular music – the deep history, back past the Sixties – it usually feels like an affectation, a put-on, a bit of a joke. Partly, perhaps, because our own showbiz tradition is rather knowing and camp, lacking the innocence and mystery of so much old-fashioned American music; that’s not how we roll over here. Even when this kind of thing succeeds, it’s thick with self-deprecating wit – there’s none of that heavy, almost spectral longing which helps make Smile what it is. For anything approaching that, I suppose (leaving aside hauntologists, with their howls of separation from a snatched-away inheritance, so’s not to overcomplicate the issue), you have to turn to those groups who went even further back, centuries back…

“Name one.”

Umm… early Fairport Convention?

“You know what, I didn’t like Fairport Convention. I didn’t like them because they weren’t Steeleye Span. You see, I loved Steeleye Span so much, because I love real rhythms… and I love the Brits, I love this place and what it has shown musically, historically. But it shows it most clearly without the apologists’ approach of an electric guitar and a trap set. A trap set?! Look, to me a trap set is New Orleans!”

Quite surprising, that – Van Dyke Parks, the experimental purist.

“Well, in 1964 I was sorry that folk music had its day. I was sorry to see it go. I remember being with Phil Ochs in his apartment with Bob Dylan, in 1964, and I was with Phil on that issue, the electrification of folk music. And Bob Dylan remembered that, when I asked him years later, and… mmm, this is good, do you want one?”

Van Dyke has started on his vegetable soup, which can only be lukewarm by now. No thanks, I say.

“But I remember, I suggested a banjo to Brian Wilson, and I was amazed that he didn’t frail, and he didn’t play Scruggs style – that’s bluegrass, named after Earl Scruggs, it’s either that or frailing, the way you play the banjo. I was interested that Brian did neither, it was just boom-de-boom-de-boom. Really outside the box when it comes to playing the banjo. But it was interesting…”

See, what you’ve done with Old Music down the years strikes me as far more disruptive than simple electrification.

“I was there when the studios were developing new capacity for instrumental combinations that had never been possible before. Having a mandolin play a solo over a wall of strings and brass – that was an impossibility just a few years before! Only by bringing a microphone close to an instrument and isolating it on a track could those new possibilities happen, so I was associated with a music which even to this day seems somehow inventive… but to a great extent that doesn’t speak to my ability, but to my good fortune. I was there at the right time for this music which seemed refreshingly inventive – intolerably inventive, in its time, actually.”

For some…

“Yeah well, this is a funny thing. I had a friend called Lowell George, who had the group Little Feat, and I don’t know whether I made it up or he made it up, but we had the phrase droit gauche – you do the thing that should definitely not be done, and which everyone else would consider passe or declasse, or for some reason you shouldn’t do it. But that’s paydirt! The road less travelled is always the illuminated route, for me. Being a maverick, not having to be hungry for approval, not being fashionable. I mean, Song Cycle is just as impossible to listen to today as it was when I put it out, and that brings me some satisfaction, that it’s not the Charleston, it’s not the Bee Gees.

“But I’ve seen a listenership develop. That record’s been a commercial failure, but for a very long time…”

The Beach Boys – Cabin Essence

Things move on, don’t they? Van Dyke Parks spent the first half of the Seventies with a day job at Warner Brothers, in charge of the newly-created Audio-Visual Department, producing short promotional films for artists like Ry Cooder and his own personal favourites The Esso Trinidad Tripoli Steelband. Every few years he’d re-enter the studio and emerge with an album as cheerfully uncommercial as Discover America, or Clang Of The Yankee Reaper.

We touch on this period, and I mention to Van Dyke that the title track from Clang Of The Yankee Reaper is one of my very favourite songs, but I never knew quite what to make of the rest of the album; he nods sympathetically.

"That’s because it’s brain dead. A brain dead album, but for that one moment, that one song, which was all I was capable of at the time."

An honesty rare amongst musicians, here.

"That album was done at the nadir of my entire life. Psychologically I was in a terrible state, I was despairing. My best friend had just died – my roommate, he was my roommate. We scattered his ashes at sea, and they flew back into our faces… a terrible, terrible insult. I was grieving, I’d just been divorced, I’d just left Warner Brothers in disgust as I didn’t want to be a corporate lackey, didn’t approve of record business practices – you know, what can I say? ‘Lost my job, the truck blew up, my dog died.’ Real good grounds for a country song.

"But ‘Clang Of The Yankee Reaper’ was inspired by a trip to London where I took out the Rolls Royce of Ian Ralfini, who was the head of Warner Ltd. He offered me his car for the day and I went down to Hanging Langford, which is a little village down near Salisbury Plain. And it turns out my great uncle, Will Carleton, had gone down there years before – he was selling an International Harvester, which was an American farming machine. He wrote a thing called Farm Ballads, a book of poetry. He would write ‘behind the heat of the team’, he said in the preface to the book…"

[This uncomfortably evocative phrase may require some explanation for all you city slickers: the ‘team’ is the pack of horses, and writing ‘behind the heat of the team’ suggests the ploughman’s perspective.]

"…so he wrote a thing called ‘The Clang Of The Yankee Reaper, On Salisbury Plain’ and I loved that title. And I looked at the poem, but the poem was dreadful."

Yes, I read it a few days ago. It isn’t great.

"No, it’s just awful. You found it? Oh my God. Just a terrible poem, but the title… he was the Yankee Reaper, see? He went around selling these things and getting money for it, and he went to Salisbury Plain and sold some equipment to the Earl Of Pembroke – always use ‘The’ when addressing him on an envelope! I read that in the secretarial handbook.

"So I was walking with Air Commodore (Retired) John C Wickham and his wife, Barbara. They were the parents of my colleague and bosom buddy Andy Wickham, who became the head of Warner’s country department – his parents lived down there and I went down to see them. We walked through the chapel; Mrs Wickham picked up the dead petals from the floor of the church. We walked out, and the rain was whipping across our faces. Jilly, the little Caron terrier, was prancing along the hedgerows… and a man was walking towards us, and that man shook the hands of the Wickhams and we were introduced. And that man was the Earl Of Pembroke, the grandson of the man who bought this equipment from my ancestor. And he was as chuffed as I was – oh, it was major chuffmanship. Me and the Earl bonded. That was beautiful, to see that an ancestor of mine had had some impact on the industrialisation of England, in a small way."

"So I went back to Burbank, to the Burbank Sound, to the normalcy of disco madness, and faced a few things – the death of my friend, how to get that dealt with and how to deal with his mother’s bereavement. I talked to Andy about how much I’d enjoyed meeting his parents for that afternoon – his mother had taken tea out to the driver who was sitting in the limo, I remember there was a big discussion about whether to take tea out to the driver… so sweet. And I told him about ‘Clang Of The Yankee Reaper’. I wanted to use that title because I thought it was a condensement of a whole moment, the beginning of the American cultural hegemony. Which has sadly affected many countries, including this one, with not always fortunate results – we’ve lost a lot of beautiful British music as a result of this rock revolution…"

Forgive me, but it still seems strange, this idea of Van Dyke as a company man. He wasn’t alone, as it happens: another great maverick, John Cale, was on the Warners payroll at the same time, toiling in the A&R department. Bizarre. It couldn’t last, and didn’t. These days, the corporate world seems at odds with everything you care about, Van Dyke. History, culture, basic human curiosity, any kind of minority interest… all now worthless and not worth preserving.

"Yes, this seems obvious to me. For instance, I took no personal offence – it was injurious, but I took no personal offence – at Warners completely passsing me over, even in the knowledge of what I did, anonymously, to help create Warner Brothers’ new image in the Sixties. Which was – pardon me, don’t mean to bark too loudly – but it was pivotal. I was pivotal to that company. I helped them bottle the blues. I helped them corporatise Delta blues and beyond, put a capsule round the counter culture, to great corporate benefit. On a secretarial salary!

"But years went by and I was rejected by Warner Brothers, a company where I had held the ‘W’ and the ‘B’ in my hand when they were putting up other names on the water towers on company property, names like Seven Arts, and Kinney… when they were taken over by funeral parlour and parking lot companies! But I wanted to protect the good name of that company and serve it, as Bette Davis had before me – although I’m not so good looking, I still had that indignation and loyalty that Bette Davis had. Bette Davis, famous of course for uttering the line ‘Who do I have to fuck to get out of this picture?’ Well, I felt like that at Warner Brothers on many occasions. So when they finally rejected me years later, yes I was injured, but then I realised what drove that decision. It was driven by the worship of youth, certainly – I’m not a brunette any more – but also what youth represents. Like the inability to read a contract, which is no small consideration to Warner Brothers executives…"

Van Dyke Parks on Discover America from Richard Parks on Vimeo.

Van Dyke Parks on Discover America

As well as the joyous contortions of ‘Sassafrass’, and a beautiful arrangement of Saint-Saens’ ‘Aquarium’ by the Esso Trinidad Tripoli Steelband, Songs Cycled features a number of tunes with fairly explicitly political lyrics. There have been various allusions to various issues down the years, but these are a lot more up-front than anything Van Dyke Parks has written before – does that reflect a change in Van Dyke Parks, or in the world?

“Well, I’ve always tried to avoid hitting a tack with a ball-pein hammer. That is, preaching to people. Beating them with my convictions. When 9/11 came and went, for example, within a matter of weeks Neil Young – ever ready to serve contemporary radio, and to be available to mass media with all the immediate satisfactions it brings – decided to put his reaction to 9/11 into a song. And the song was called ‘Let’s Roll’, and the message of the song was retaliatory: ‘Let’s get those ragheads.’ But 9/11 was as traumatic to me as the assassinations of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King… it was absolute catastrophe to me, and part of why it was such a catastrophe was that I didn’t understand it. So my response was not ‘let’s roll’.

“Now, I knew I had some responsibility to write about 9/11 because my daughter had been in New York, running from the towers; that wall of ash, the human remains and the disintegrated buildings snaking its way uptown. She was due to attend a class at NYU that morning, and she was on her cellphone to me, and I was at home looking at this image… I’d just stepped out of the shower, I was rather fuzzy, I had no idea that this was something that was really happening. But it became obvious very quickly what it was, and she said, ‘What should I do, Dad?’ I said, ‘What are you doing now?’ and she said, ‘I’m running north as fast as I can.’ I said, ‘Good thinking.’ She ran to someone’s apartment and found protection on 23rd Street.

“So it came close to home. Then there was the revelation that the disfranchised world, the Third World, was pissed off, and one thing they were pissed off about was the obscenity of the developed world – which I could understand, having examined the words of Christ, who spoke twenty-two times on the subject of greed. But it revolted me. It stilled me. I was left stammering. And that stammering became the lyrics to the song called ‘Wall Street’, which is the product of my own wobbling faith, my reservations about greed, and also my fascination with two flaming figures that united in flight on their way down to the concrete. At the moment my daughter was running, four blocks away from Ground Zero was Nadja, the daughter of Art Speigelman, the Pullitzer Prize-winning illustrator and author. Her father rushed over to get her out of school before that second tower went down – and you can imagine the adrenalin rush of a parent at a time like that – and she looked up at the sky and she said ‘Dad, the birds are on fire…’

“So there’s a difference, you see, between Neil Young’s instantaneous certainty and my delayed uncertainty. But political? Absolutely, fundamentally.”

These themes of sadness, confusion and anger recur, in ‘Black Gold’ (about the Prestige tanker spill and “the chicanery of Big Oil”), in the self-explanatory ‘Money Is King’ and in the opening track, ‘Dreaming Of Paris’.

“My wife and I took a flight to Paris, where I was going to conduct an orchestra – some arrangements I did for Rufus Wainwright – underground at the Louvre, with the pyramid overhead… this is a different Paris than the one my wife knew years ago, when she was running a small shop in the flea market there, the Marche Malik. She had left the United States in 1969 after the death of Martin Luther King in Memphis, her home town. She’d had it with the gunplay so she expatriated to Paris and lived there for six years, selling clothes in the flea market. And we got on the plane to return to Paris, the Paris she had loved – her first revisit – and that was the night George W Bush chose to drop the bombs on the cradle of civilisation, that place called Baghdad. The song is all about the futility of war, the inappropriateness of bellicosity, the lessons we learned in Vietnam, all lost on George W Bush.”

Also appearing on the new record is ‘The All Golden’, a piece from Song Cycle, re-recorded without the off-centre orchestra and overwhelming tape delay which gave the original (and most of its parent album) that peculiarly disorientating feel.

“It’s a song which I was determined to reinclude, but stripped bare, to answer any charges of obfuscation, to make clear my reservations about war, and to remind myself of the lessons I learned in my youth. It also offers a nexus between my first album and arguably my last.”

Do you think so?

“Do you mean do I want to do another album? I would like to do another album. I’d like to play piano forever, too. But the fact is, I’m 70 and it’s very hard to deal with the physical and financial challenges. I look at it this way – I’m content right now with this release, I’m amazed that this British company, Bella Union, have given me the opportunity to have an album, because I exhausted every possible… I mean, I went from pillar to post to find a patron, just to put out this record. Nobody. I would say ‘don’t get me started,’ but I would love it if you did, on the futility of trying to support oneself as a musician. I’m breaking even – that’s where I am. I don’t have a swimming pool. I break even. I just want to assure you…

“I only learned that there was a commodity value to songwriting when I did my first single, on MGM. I recorded ‘Farther Along’ and when they said ‘Who wrote that song?’ I said ‘The Hopi Indians’ because I wanted the Indians to get the money. Well, my attorney said ‘What did you do that for? Nobody’s gonna make a dime! The Hopi Indians aren’t signatories to BMI’ (the American Performing Rights Society) – I had no idea. But I learned about this, I studied it. I thought wow, this is a way to make money. There’s a premium put on intellectual property. But in those days a loaf of bread cost two cents, and the author of a song would get five cents a song. And these days a loaf of bread costs two or three dollars, but a song gets less than one cent – a fraction of a cent! Everybody’s downloading now. Fractional revenue for songwriters.”

And Van Dyke Parks – one of the gentlest raconteurs you ever could hope to meet – gets very nearly angry.

“What are we doing to the arts? We get clever attorneys – the heat behind the beat – to drive people to the irreducible minimum. We do absolutely anything to make it impossible for the arts to be anything other than decorative…”

It’s the future.

“It’s disgusting.”

Van Dyke Parks, ‘The All Golden’, performed in 2010

Before I leave, Van Dyke talks me through the luscious instrumental album he put out for Record Store Day, Super Chief: Music For The Silver Screen. It’s a compilation of his soundtrack work, re-recorded and re-assembled into something like programme music: an orchestral representation of the most important journey of his life, coast-to-coast on a luxury locomotive in 1955 – coming west to Hollywood! Every track illustrates a memory from along the way: "A dining car… a bar upstairs… meeting Joan Crawford, hearing folk music… then we end up at the Chateau Marmont…"

As Van Dyke points to a picture on the sleeve – himself as a child, sitting next to Grace Kelly – the past slants into the present again, but this time there’s no confusion, no disorientation, just an enormous warmth. I head back home. The sun’s gone in. Retracing my steps is simple enough. Easier than getting here.

In an age of incuriosity, with the past devalued and the future so very forbidding, the music of Van Dyke Parks makes more sense than ever; sounds better than ever. Like the state of California – so I’m told – it takes some time. It doesn’t reveal itself immediately. So, what’s the problem? We have all the time in the world.

Songs Cycled is out now on Bella Union