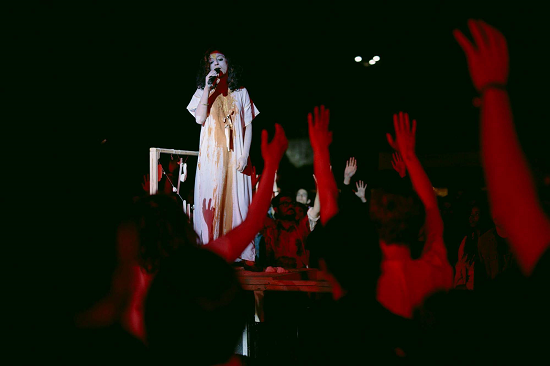

Photos of UKAEA at Milhões de Festa 2018 courtesy of Dan Jones

At Supernormal Festival 2017, in the grounds of the Brazier Park estate in Oxfordshire, Dan Jones’ techno project UKAEA morphed into something extraordinary. The festival had called for artists to play in a wonky triangular barn known as The Vortex. Together with his girlfriend Charlotte Blackburn, who had, as she puts it, “dabbled in noise and performance work at Central Saint Martins, making live work in squats, churches and shop windows,” they came up with a proposal.

“Charlotte was like, ‘I can get involved and design a holistic thing, a world people can walk into, provide catharsis you won’t get at a usual show,’” Jones remembers. “So I expanded the music accordingly.” He enlisted friends and collaborators; Amdeep Sanghera who’d contributed djembe drumming to previous UKAEA gigs, the leader of North London noise titans Sly & The Family Drone Matt Cargill on electronics, violinist John Hannon, vocalist Deyar Yasin, and four additional performers, Jessica Doyle, Emily Sandeman, Rachael Heathcote and Kaya Moore.

“I gave everyone instructions beforehand, and the combination of excitement, feeling exposed and being utterly terrified somehow transferred into an infectious and raucous intensity which we could have never imagined. The people of Supernormal brought the magic,” Blackburn says.

“I just remember getting to the Vortex, getting sound-checked, dunking myself in white clay, then watching the people come in,” recalls Sanghera. “There was this incredible energy even before we played, a realisation that this thing we’d been driving towards was now actually happening…”

Yasin began the show singing an a capella Arabic ballad. She was initially supposed to do so outside the venue, to usher people in, but the soundman didn’t allow it. “He just stuck her onstage and said ‘here’s the microphone,’” says Jones. “I saw this galvanised look on her face, it was amazing. There was this incredible sense of euphoria. ‘Oh God, we’re actually doing something,’ and I think that snowballed to the whole crowd.”

Immediately, the collective dissolved the barriers between audience and artist as costumed performers scattered themselves among the crowd to encourage both confusion and participation. Jones music took the shape of a hyper-compressed rave: a long build, peaks and plateaus and an eventual wind down. By the end, everyone was covered in white clay. tQ’s John Doran wrote about the show in an article on New Weird Britain for Vice a few months later: “The beats and the bass stop and a huge reverberant drone throbs in the barn before everything kicks in again with the speed and intensity of jungle, eventually moving up through hardcore bpms into pure gabba as more and more clay-faced ravers start losing their shit. I’m leaping up and down now. People all around me are screaming and punching the air furiously, heads evaporating in explosions of threshed hair.”

Visuals by Stormfield

Sanghera doesn’t remember much at all. “It’s almost like I wasn’t there,” he says. “Every time I looked up I either saw Dan and Matt trying to shake their head off their shoulders, or a mass of clayed-up bodies writhing around in some sort of joy… I don’t think we could have anticipated that!”

The following summer, UKAEA played another, different show at Portuguese left field music festival Milhões de Festa. “To give you a rough idea,” says Blackburn, “members of the audience carried Deyar who stood on a large wooden platform adorned with porcelain remnants, across the festival site in a procession, many people following behind, to a plinth centred in the crowd. A pre-recorded chant was amplified and distorted in the stage arena, everybody watching Deyar. I signalled that everyone should get down, and about 300 people just instantly sat down to listen to Deyar sing unaccompanied, it was an epic entrance to a set.”

They have performed on other occasions, and Jones also performs as UKAEA solo or with reduced line-ups, but it’s Supernormal and Milhões de Festa that represent the two pinnacles of the project as a large ensemble. “They were almost polar opposites in that at Supernormal we were completely ramshackle, there was a lot of happenstance,” he says. “A lot of stuff just fell into place that could have gone completely shit on another day, and everyone [in the crowd] bought into it and it ended up as a symbiotic relationship where you amp each other up and up.” Portugal, on the other hand, “was planned down to the last detail. We had a team of local carpenters there building structures so we could transport Deyar over the heads of the crowd.”

It’s Blackburn who heads up production for the big ensemble shows, using drawings and a “very chaotic timeline on a big sheet of paper” to sketch out a rough plan beforehand. “I think about how all the elements meld together, I make visuals, bring the materials, devise actions and play with the audience, all in the pursuit of an immersive show that breaks down the fourth wall,” she explains. “There’s nothing worse than an inattentive audience, and I’m fascinated by what audiences will and won’t do. I’m not that interested in rehearsing, it’s impossible to practice something that’s so reliant on the audience.”

Ritualistic is a word that, in music parlance, has become somewhat overused, but I put it to Jones that perhaps a UKAEA show is one of the few occasions it’s actually valid. He disagrees. “The term doesn’t sit well with me,” he says. “There isn’t any set kind of state we’re trying to achieve. It’s cathartic for everyone but in different ways, whereas a ritual has an objective. And yeah, there’s also those connotations, of everyone being so keen to elevate what they do to the realms of something beyond a rock show, when what they’re really doing is smearing it with this semblance of fake spirituality, Dungeons And Dragons nonsense. It’s not our vibe at all. We like all kinds of music but we’re ravers.”

Born in Wrexham and raised in the small Welsh village of Pantymwyn, free raves in the Welsh hills were formative for Jones as a teenager. “I was in various bands, but I simultaneously had an interest in the techno scene,” he says. “If I was to walk around town with bright green hair, some lad would probably punch me in the face. But if I met him at a rave he’d shake my hand and go ‘how’s it going boy?!’ It was this mutual ground where all the different groups of people who wouldn’t get along would have a right old time in the middle of nowhere.” It wasn’t quite the archetype of techno utopia, however. “If you’ve seen Dead Man’s Shoes and the kind of small town gangster depicted in that, the party crew began to resemble them after a while.”

To some extent, everything UKAEA does now, with its decentralised staging, impetus on the communal, and Jones’ command of tempo, is like a rave. “There’s a total continuum between the full performance, with all these props and carpenters and materials, and me DJing in a basement with just a flashing red light,” he says. Raves are also where he first met many of his collaborators. Once he could drive he started going to Liverpool techno night Voodoo. It was there, one night in the late 1990s, that he met Sanghera, then a Mathematics student at the city’s University.

Jones later studied ethnomusicology, but didn’t finish the course. He moved onto modern composition at King’s College, but dropped out once more, focussing instead on “a really complicated but violent and yobby and confrontational post hardcore band called Nitkowski.” UKAEA was a techno side project, “I was trying to be Robert Hood or something,” but began to develop in its own right. “At some point I realised the stuff I’d learned on the ethnomusicology course was actually relevant and started using it properly. I expanded out from there.” He started jamming with Sanghera, who had played with north Brazilian samba reggae musicians, and studied under West African master percussionist Jahman Sillah and his family both in Birmingham and Gambia, Jones and Sanghera’s sessions a precursor to the grand expansion of the Supernormal performance. Jones met Yasin at a Sly & The Family Drone gig in 2013, and Blackburn at a Wharves gig the following year. (He lives in a North London warehouse with members of each).

As well as forming the core of those crucial live gigs in Oxfordshire and Portugal, all of those artists play a key part on UKAEA’s first album, Energy Is Forever, released earlier this year by Hominid Sounds. Blackburn makes her first vocal contribution on the pummelling ‘Benzene Hex’. Sanghera’s percussion, adapted from what he played at those gigs, provides a thunderous spine. Yasin’s vocals, all in Arabic, are woven throughout the record. Other frequent live collaborators like Sly & The Family Drone are on the record, as are friends working with him for the first time like inimitably intense Nottingham noise musician Aja Ireland. Jones’ father – a supportive parent who can sometimes be seen hanging around UKAEA gigs at 3am getting ready to drive clay-covered performers to their next show – contributes the sound of an “absolutely fuck off massive bee that he caught in his house. He just emailed me one day saying ‘I recorded a bee’,” Jones laughs. “You’ve gotta find stuff to do in your retirement I guess!”

Middle Eastern and African influences are prominent on the record, influenced by Yasin and Sanghera’s contributions as well as Jones’ own history in ethnomusicology. As a white, British artist, however, “the thing I think about a lot is how to do that sensitively,” he says. “When I try to use elements from traditions that aren’t my own, there has to be some kind of solid exchange, dialogue or learning experience, and I try to do it with heart and sensitivity; otherwise I’d just be an information tourist at best. Also, I make negative money off this, so there’s no danger of, er, doing a Paul Simon.” His collaborators help him stay on the right side of the divide between influence and appropriation. “I think I’ve got a good group of people around me would just tell me ‘that’s bollocks’ if I was doing it wrong. It did happen at one point. Initially I put this chugging 4/4 techno beat over the ending of ‘Qandisa’ and I got a phone call from Amdeep at a ridiculous time in the morning saying, ‘Mate, it sounds a bit Afro Celt Sound System.’ After that I said to Amdeep ‘Right, you’re on Womad watch. If anything sounds like it would get us booked by Peter Gabriel, tell me and we’ll knock it off.’

“I think ultimately the goal is to make music that sounds like it’s from nowhere,” he continues. This relates to the visual aesthetic of UKAEA, which often uses images of nuclear power stations, missiles and submarines. The artwork for Energy Is Forever is a photograph taken by his father of the decommissioned Trawsfynydd nuclear power station in Wales, which they’d drive past as a family when on their way to holidays on the Welsh coast. His website, headed with a bastardised version of the actual United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority crest, is scattered with fragments of quotes and austere nuclear and post-industrial photographs.

“It’s an attempt to imagine how we might begin to reassemble a form of culture from remnants after an apocalyptic event, the effect of which has been a massive loss of information and collective memory. They become almost objects of reverence, because people know that they were important in the past, the reverence is still there, but the meaning’s lost.” He was partly inspired by Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic novel Riddley Walker, set 2,000 years after a nuclear apocalypse in a new civilisation trying to recreate ancient weaponry. “I don’t know if I’d call it sci-fi, it’s about the death of science,” he continues. “Although it’s probably important to state that I’m not on the side of these so-called ‘free speech’ crypto-fascist accelerationist bellends. This post-apocalyptic fascination is meant to be a warning, not a manual!

“To start with it was quite flippant,” he continues of his interest in the aesthetic. “But I’ve got into the idea that I’m building a larger scenario that has concurrent elements in it.” The ‘world-building’ he talks about at his live shows, is a part of this. “I can envisage a post-apocalyptic place and depict it through music or words or imagery, but I don’t want to make too much of it.” UKAEA isn’t an exercise in science fiction, he insists. His website doesn’t offer much in the way of details or plot, but rather provides “a wildly chaotic load of psychobabble that I think enhances where I’m coming from.” The world built at one of their shows can be vastly different for every single person performing or watching; this is why it’s more like a rave than a ritual.

Like the live shows, Energy Is Forever is a distinctly collective effort; it features over a dozen contributors from across the country. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, much of it was recorded remotely. He had to plan the order in which he sent layers of each song to different contributors. “It’s a weird way to do things, but at the same time I enjoyed the clinical nature of it,” he says. He took one djembe rhythm that he and Sanghera dubbed ‘headfucker’, cut it up and scattered it across different tracks. “He started to apologise to me, saying how he had bastardised and destroyed the take, but I was shocked, in a great way, at what he had done and how he was able to take something and make it completely unrecognisable,” Sanghera recalls.

For Yasin, whose creative process would often depend on “getting smashed or being in the same space with the people I’m working with,” lockdown forced her to leave her creative comfort zones. “I happened to be going through a sober spell at the time,” she says. “My stuff always ends up being either really personal and emotional, or about the fucked-upness of the world. I have to really go somewhere else, so doing all the of the singing sober was a bit taxing as I’m used to having a booze covered blanket around me to do these things. But in other ways, it was a moment of like, ‘oh wow, I can do this sober!’”

Though UKAEA is Jones’ project, he’s unafraid to let it take shapes outside of his own control. At live shows, he’ll sometimes be set up away from the centre of the action while the rest of the performers wreak pandemonium among the crowd. “Charlotte’s in charge of that stuff because she’s an expert in not doing too much. If it was down to me I think it would be overblown and terrible.” On Energy Is Forever, he was careful not to offer too much of a brief to his contributors, shaping his own work around their contributions, not the other way around.

“Dan is really good at just letting people do what they want to do,” says Yasin, who sings entirely in Arabic on the album. “Being an Arab who has lived in Europe since I was four, identity issues are rife within me, and just uttering words, making sounds in my mother tongue, helps me connect more deeply with my heritage and identity.”

Jones only named the album’s opening track ‘Qandisa’ – after a North African female spirit who in one manifestation of the myth lured colonialists into the wilderness for locals to come out and butcher – after the track was completed. “The title was applied later, when Deyar translated the lyrics for me,” he says. “I know it sounds like a ballad, to start with, but there’s a lot of vitriol in that song from Deyar’s point of view.” A lot of the titles are applied retroactively, or from meanings bestowed by his collaborators’ work. ‘Benzene Hex’, the song to which Blackburn contributes vocals, is an extension of her own studies on the ecological and societal violence within mining practises, for example. “Maybe it has to be that way, because I don’t really know what the song is about for a while,” Jones continues. “The people who contribute to it have a say as well. I think by the end it can mean something completely different to what I thought it would mean.”

The biggest triumph of Energy Is Forever is that it manages to exist in a similar world to their live shows, one that abounds with rich atmosphere yet remains completely open to individual interpretation. Stripped of the multisensory bells and whistles of a full-blown UKAEA show, the album is remarkably holistic in the “balance of human and mechanistic sounds” Jones sought. Like a condensed version of what you’d hear at one of those gigs. “Everything had to be condensed. I wanted to provide a cross section of what I’ve done and the ideas that I’ve had that would involve elements of other people from whatever this strange beast we try to call a scene sometimes is.”

UKAEA’s new album Energy Is Forever is out now via Hominid Sounds. You can stream and purchase it here.