When two thirds of the Tropicalia trio Os Mutantes regrouped for a series of live performances three years ago, I wasn’t in the audience. It was a deliberate absence: I’m not good with psychedelic-era revivals, preferring to hold bands like Mutantes, Love and The Beach Boys hostage in my room, on overplayed records and jumping CDs, acting out their mercurial, troubled pop dramas forever and unchanging. These physical reappearances ossify what should be beautifully transient music, amid a live atmosphere that combines religious fervour with slight embarrassment. That’s why – in case anyone wants to know – I went to the Pet Sounds show, but not the Smile one.

Listening to the live album released after the London concert, however, it’s clear that Os Mutantes handled their comeback with aplomb and glee. Their first appearance in the UK – the country whose music inspired São Paulo brothers Sérgio Dias and Arnaldo Baptista to make their own out-there sounds in 1965 – turned the concert hall into a triumphant party zone full of fanfares, harmonies, squelching guitars and samba rhythms. If original singer Rita Lee was absent, presumed playing Brazilian stadia, and the Baptista brothers’ uneasy truce was to be only temporary, the recording nonetheless bubbles with ebullience and an audible lack of regret.

Three years later, Mutantes are back on the road, and Sérgio Dias Baptista is on the phone from Henderson, Nevada. But Mutantes are not doing the nostalgia circuit; instead, at least the half their current set is material from new album Haih Or Amortecedor. Perhaps one would expect nothing less from an old Tropicálista. The name given to the short-lived music and arts movement that brought together Brazil’s most avant-garde in the late Sixties, Tropicália has come to signify a body of music that was eclectic by design, sonically adventurous and inescapably Latin American. Tropicália’s musicians, informally led by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, syncretised the new psychedelic sounds of Britain and the US with bossa nova and batucada, funk and jazz, and a theatrical sensibility that often called for orchestras and sound effects alongside wah-wah pedals and percussion. Tropicália, even at its most tripped-out, is razor-sharp, prescient music, with few exhortations to turn off one’s mind, relax and float downstream: under the military dictatorship that came to power in Brazil in 1964, this attempt to redraw musical and cultural boundaries was imbued with a real-time urgency. It is probably the most seductive radical music you’ll ever hear, from Caetano Veloso’s lush Situationist love song ‘Enquanto Seu Lobo Não Vem’ to the louche funk of Gal Costa’s ‘Cultura e Civilizãcao’, and Tom Zé’s tongue-in-cheek ode to the ‘Parque Industrial’.

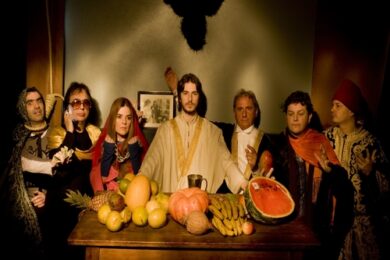

Os Mutantes were the youngest members of the movement, teenage Beatles fans with homemade instruments given to dressing up as conquistadors and brides. In any other context, this, and their infectious songs about getting stoned and praising Lucifer, might have passed for whismical high spirits; in Sixties Brazil, they were politicised by default, and their magpie-like approach to genre chimed with the Tropicália tenets of mixing styles and influences. As Gil and Veloso were exiled to the UK in 1970, Mutantes recorded increasingly sprawling, prog-hued albums; Rita Lee began to forge a solo career; and a combination of in-fighting and a prodigious taste for LSD resulted in Arnaldo Baptista’s departure from the band in 1973, leaving Sérgio Dias to dissolve Mutantes in 1978.

In recruiting fellow Tropicálista and poet Tom Zé and renowned songwriter Jorge Ben as contributors to Haih Or Amortecedor, Sérgio Dias references his musical past; yet the new album is surprisingly free of nostalgia. Perhaps not so surprising, however: that Zé’s maverick take on pop music had come through the last few decades unscathed was apparent on his last album, 2006’s Estudando o Pagode – a mash-up ‘rock operetta’ about street samba and gender relations. Zé’s collagist approach pervades Haih, from the abrasive, darkly catchy ‘Querida Querida’ to the arch percussion and sound effects of ‘Samba do Fidel’. But there are also rather touching traces of vintage Mutantes joie-de-vivre: Sérgio’s self-penned ‘O Mensagiero’ forefronts twinkling guitar and cosmic lyrics, while ‘Neurociencia do Amor’ is a wigged-out rock & roll romp about “the music of love” that could have come straight from their 1968 debut.

After Arnaldo’s brief reappearance, the elder Baptista has once more left the group, and singer Bia Mendes now takes on the vocal duties of Rita Lee, but Sergio is adamant that the album is fundamentally Mutantes music. Indeed, it does have much of their trademark playfulness, warmth and spikiness; something of the idyllic yet synthetic ‘Tecnicolor’ vision Lee sings about on Mutantes’ 1971 Jardim Elétrico album. The guitarist is clearly stoked both by the interest in Mutantes’ past career, and the rejuvenating effects of making a new piece of work; he exudes the avuncular optimism peculiar to counterculture veterans experiencing a new lease of life, and has recently custom-built a brand new guitar.

How did Haih Or Amortecedor come together?

"After the Barbican, the first thing I said was, OK, let’s do more music, because there would be no sense in putting the band together and just playing old stuff. So during that period when we were doing the tours – 2006, 2007 – I started to write, and I was fortunate enough to re-encounter Tom Zé. I started writing with him and he became a great partner. But it is a different experience to make music under the Mutantes umbrella; for example, if I do a song as a solo it is totally different. I don’t know how to describe this – it’s very magical.”

The new album sounds very, well, new. Also there are influences from around the world, there’s a song about Baghdad, there’s even a Hindu mantra…

“Yeah, I did ‘Gopala Krishna Om’…what can I say about that? I’m a weird guy! [laughs] Listen, when I was a kid I studied sitar with Ravi Shankar. He gave me my sitar. That was when George Harrison was also doing his studies. Then Ravi invited me to go to his school in India, but I was not able because I was working with Mutantes, and I was dumb enough in not putting my feet down and saying, I am going, you know? But I had those influences then, and I think this comes out in the album.”

It’s very eventful music, which is something that’s also common to Tom Zé’s work. Was it easy to find space for one another?

“Yeah, we totally complemented. I think he’s one of the best partners that I have ever had in terms of writing. This is for life, you know!”

Did you know each other from before?

“Well, forty years ago we met, but I was sixteen years old – I wouldn’t even be able to talk to the guy! You can imagine, his level of intellect and my level of intellect when I was sixteen: basically guitars and – not even girls! There was a huge gap, you know? We brushed only at the time. But now, it’s a beautiful thing.”

You and Tom are also both very interested in sound and noise…

“Yes, I just built a guitar for this album, because I didn’t want to record with the old one. I didn’t want to play in the 21st century with something that I built in 20th century. So I built it from scratch, this one; it’s still the prototype, like the 00000001. But it sounds great, it’s an excellent instrument. It definitely shapes the way that I play.”

I read that in the early days of Os Mutantes you’d make your own kit. What kinds of things did you make? Pedals?

“We had pedals that did not exist [elsewhere]; three pedals that were basically our creation, and I had that sewing machine thing [the insistent buzzsaw guitar sound that characterised early Mutantes tracks like ‘A Minha Menina’ came from a fuzz pedal driven by a sewing-machine engine, a contraption built by Sergio and Arnaldo’s brother, Claudio]. We were finally able to digitalise that so now it’s possible to use again, because then it was just a mechanical thing that would just blow up every thirty seconds. So it is great that technology has come to a point that you can really do it.”

Are the possibilities of new musical technology exciting for you?

“We didn’t really want to lean on the things that are available. We didn’t use any of those VST instruments or computer stuff; we were basically trying to get a more acoustic, more real sound, using an Egyptian oud and a bunch of different flutes. On ‘Samba do Fidel’ that’s a cello playing the bass…so we were just fooling around with everything.”

When you were making music in the Sixties using homemade equipment, that was mainly through necessity, wasn’t it?

“For sure. There was nothing in Brazil, not even strings – we had to buy steel to make strings. There were so many things you had to build. So I think that became part of us. Like when we heard the reverse tapes on Beatles songs, we didn’t know what the hell that was. The closest thing we could get to the sound of the hi-hat reversed was an insecticide pump, so we used that.

“We were kids, and kids want always to mess around with everything: if it was too simple, we had to complicate it! You know when you’re a kid and the first kiss is such an important thing in your life, it’s basically the same thing that drives us looking for the new stuff: it’s always to have that fresh feeling of ‘what is this?’”

How do you retain that, after playing music for as long as you have?

“Being young for a longer time! [laughs] I’m younger for longer than you! I’m a kid! This thing of immortality that every kid has, it is a more conscious thing now, for sure, but you’ve got to cultivate it otherwise you start to wear a suit and tie in your soul. Then it’s trouble.”

Is it harder for young musicians for that have attitude now, do you think? We’re all so much more aware and worried…

“No, I think during the Eighties and Nineties musicians were going through a hard situation, but now, with the internet, everybody’s free and it’s a great moment. I think it was a must for us to be able to be alive now, as Mutantes; it was a very good thing that we hibernated during the Eighties and Nineties because I don’t think we would have had a place in the sun. Now, there is much more freedom, the kids are much more active, individually, and they don’t give a damn about any of the success formulas, which is beautiful to see. I think that [the internet is] the new government that’s going to come over the world, maybe. It’s the great anarchist thing.”

We were talking earlier about your experience at the Pitchfork festival, watching the audience trying to sing along in Portuguese the way you’d have tried to sing along to English music when you were younger. I’d like to talk a bit about language – the new album is pretty much all in Portuguese, and I know I’m missing a lot of the ideas in the lyrics by not knowing the language, especially as Tom Zé is so good with wordplay.

“Well, you guys are gonna have to work harder to try and understand it! As we did with English. In the album sleeve there is a translation for each song, but it’s not very accurate. There are things where we wouldn’t be able to do it in English. Like, ‘2000 e Agarrum’, that won’t make any sense in English…it’s a word game with ‘2001’ which is ‘2000 and grab someone now’.”

Right…

“It has to do with a dance…all the games that Tom made with the lyrics are impossible to translate.”

The use of humour and satire still seems to be important to you – humour as a way of attacking certain subjects.

“For sure, there’s a lot of sarcasm in it.”

What are you being sarcastic about on the new album?

“The situation of the United States versus the old USSR, which we use in ‘Hymns Of The World’, we put the USSR anthem with the Brazilian anthem and the US anthem. It’s hard for us bystanders to understand the United States without an opponent like the USSR. For example it was so boring to see Bush and Chavez or anything like this; it was much more interesting to see Kennedy against Kruschev [laughs]. The interaction between America and you guys and the Soviet Union brought a lot of good things in terms of the competition in science, and also in the development of – how can I say – the humanity of what it is to be a human being. And now, with the lack of the USSR, America is very lonely. They are going to have to do something about it…maybe we have to wait for the green guys to come down and make them some nice challenge…”

Well…they’ve certainly made enemies of Iraq, Afghanistan…

“I think that is a lame thing comparing to the USSR situation. The Middle East thing is about oil, but USSR was much more ideological, the Communists versus Democracy, and this is what brings new ideas to flourish. I don’t know…I’m not wanting to diminish the situation. I think 9/11 was an awful thing. But there’s nothing that can defy the human race. I mean, the situation then between the USSR and America was a matter of ‘Is humanity going to survive it?’ And that was literally all of the world.”

So you think political tension makes for interesting culture?

“Yes. But anyway, this is just one colourful thing we used on the album. There’s a bunch of it [in ‘Samba Do Fidel’]. There’s Obama there, there’s Bush, there’s Chavez, there’s Lula…And there’s a lot of criticism about Brazil, things like how the football rules the country. But it will lose a lot in the translation.”