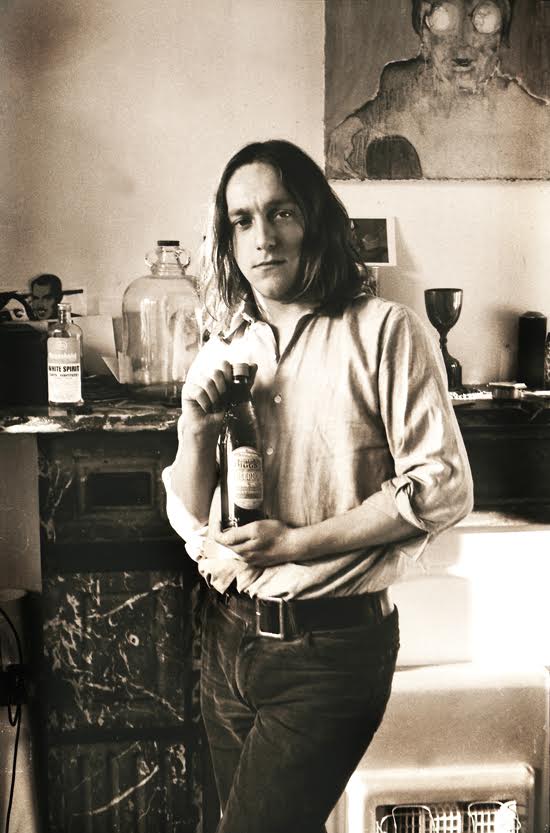

Tom Sheehan in Dulwich, 1970, by No Neck Neenan

Tom Sheehan’s new book, Paul Weller In Photographs 1978-2015, is available now via Flood Gallery

Tom Sheehan, smudge to the stars – and depending on which ex-Melody Maker writer you believe, the second most evil man in music, or the music lover whose generously proffered compilations of rootsy American music have blown the minds and broadened the musical palettes of more recording artists than you can shake a dobro at.

Unflappably professional, tirelessly gregarious, pragmatically adept at knocking up a cover shoot in ten minutes flat in a Holiday Inn corridor when needs must (and frequently needs must), he’s the Camberwell kid who grew up to love the Grateful Dead and Gram Parsons, turn a frankly sceptical eye on punk, baffle lairy Manc lineups with only slightly overegged cockney rhyming slang, and slip a pair of handcuffs on Snoop Dogg at a particularly delicate juncture.

Over a photographic career spanning five decades, Sheehan’s caught a small army of recording artists on film (and the pixels that came after), and shot most of the biggest names through multiple albums, haircuts and bass players. It almost seems strange, therefore, that there hasn’t been a covetable Sheehan-on-the-coffee-table volume before now. But it’s arguably less surprising that the first such outing would involve the ever-changing barnets and whistles of the Woking Wonder.

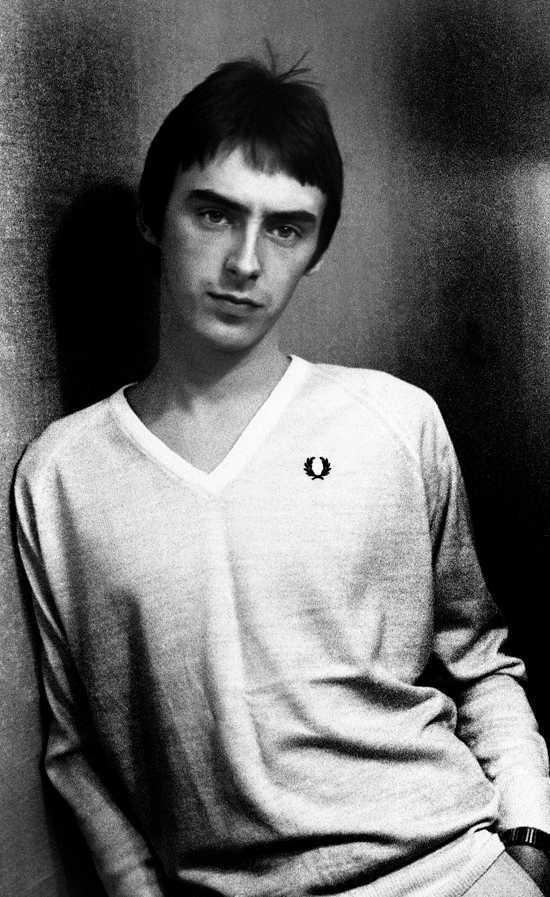

If anything is proved by Aim High: Paul Weller In Photographs 1978-2015 – which comes served up a treat in seriously strokable slipcase, beautiful paper stock, an appropriately gruff-and-generous introductory note by the subject himself and all the rest – it’s that beneath the bonhomie, work ethic and affability that made countless weekly magazine covers, album sleeves and press photos come off without a hitch for so long, there is a talent at least as singular as the musicians Sheehan loves best.

The Jam – ‘Start’

It’s hard to believe I’m finally seeing your photos served up properly, after all those years we spent at Melody Maker, which disseminated them on something not far from bog roll. How did you hatch the idea for Aim High?

Tom Sheehan: We did a Mojo session last year at the 100 Club and Paul [Weller] said, "Tommy, you should do a book." I thought he was saying that I should do a book of my stuff, and then I realised that he meant a book of our relationship together. I never shot The Jam first time around – I was still [a staff photographer] at CBS Records – but then I got them in 1978. I had about 4 or 5 encounters with Paul in The Jam and then 8 to 12 encounters with The Style Council, and then the rest [solo], which ends up being about 32 or 33 encounters. The only other people I’ve shot that much would be The Charlatans, and The Cure, certainly, and the Manic Street Preachers.

I love this song, and the enthusiasm of it, with that intro referencing something we just might have heard before. Paul isn’t afraid to utilise stuff that he’s known from childhood that influenced him, and it’s probably better to do it in kind of an obvious way than try and be subtle. So he ripped off ‘Taxman’ – if only we could all do that!

Aim High shows he was a young man to whom poise and style really mattered.

TS: Oh yeah, he’s always done that hasn’t he? Although there might be a few pics in the book where you might say, "Oh, Jesus Christ." But let’s face it, we’ve all had a dodgy haircut or a dodgy shirt.

It’s a terrible word, but it’s about presentation. It’s treating the job that he does like – I won’t say showbiz, but that kind of thing. He’s dressing, and it isn’t just for the stage, it’s for his life. A well turned-out chap… who happens to write great songs.

You could say that focus on style is part of working-class culture.

TS: Absolutely. I grew up in a working-class environment. My parents were immigrants from Ireland. When mod came about, it was about saving up your paper round money and buying a pair of shoes or a shirt. It’s your Sunday best, but your Sunday best all week.

Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers – ‘I’m Not a Juvenile Delinquent’

You said this was one of the first singles to really grab the young Tommy Sheehan’s ears.

TS: I think maybe my sisters had this one; for some reason I could remember the words to it quite easily. It’d have been about 1958, I’d have been about eight.

We grew up in Camberwell, with no electricity in our flat. We had a wind-up gramophone, and my two older sisters would take it downstairs [to the communal square]. We’d crank it up and all the local kids would come round, and all the Teds, with their 78s and 45s, and they’d be dancing and bopping and jiving in the square. They would have been about anything from 12, 16, 18 top whack. I remember me and my twin sister sitting on the step, and watching them dancing around, and my mum saying, "Thomas, it’s time for bed", about half seven, eight o’clock on a summer’s evening.

You were a music fan from early on.

TS: Oh god yeah. It was the most important thing. Music, football, fishing. I started a paper round quite early on. We didn’t have a lot of money – we were actually poor. But both my elder sisters were working and if we wanted to buy a record we’d vote on it, and I’d put my sixpence or shilling in. Later when I had enough money to buy my own records, it was up at Loughborough Junction at a shop that sold electrical appliances and at the back they always shad a few racks of singles, and I bought ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ by Them, which I probably heard on Radio Luxembourg. It was brilliant. It stills sounds fresh.

I would have dearly loved to go to art college, but I think I was a shit painter. I wanted to be a photographer, because I loved music and loved photography. It wasn’t expected of me and my people, from where I came from, to go to university. But I had hankering toward the art world. From Camberwell you can get up to The Tate quite easily by bus, and I used to spend a lot of time there on holidays and at weekends. I went to football matches, but I got fed up standing about in the rain, long before comfy seats and all that. And I didn’t have enough money to spread it around, so on a Saturday I would go to The Tate or the National or the Courtauld Institute. I just thought, no one’s going to educate me other than myself. I went to a Catholic school. We had religious devotions every fucking day, and Saturday mornings was spent doing a confessional and Sunday at mass, you know.

I took a couple of girlfriends to galleries over the years, but I always think it’s a solo pursuit, looking at art. And sometimes listening to music is a solo pursuit, too, because things that mean so much to one don’t mean a jot to someone else.

Did you have a camera by then?

TS: That happened much later on, cos I couldn’t afford it. I would have been 17, 18 before I got one. My mum wanted me to be a priest or an electrician, but I wasn’t going to have it. I ended up working at a place in Pollen Street off Maddox Street, the Times Drawing Office, and they had a darkroom and did litho printing and silkscreen printing, and I went in the darkroom, worked there for a year. Worked for a couple of years for publications in Morton Street, doing photographic printing. Then I worked for someone over near Hatton Gardens, near Farringdon, assisting in the studio, setting up lights and all that, and printing as well. And then finally just being an assistant, before I moved up to Sheffield for a few years.

What were you listening to?

TS: I’d always been an avid music paper buyer, but I didn’t like a lot of UK music. The Sweet, even Bowie, I just thought was fucking rubbish. Boring. Style over content. I was already ensconced in American music anyway, so I just dug a little deeper. In those days, when you bought Rolling Stone magazine or one of those more adult mags from across the pond, they’d have ads for Warner Bros records: Ry Cooder, Randy Newman, Captain Beefheart. It was a fantastic label back in the day, a genius label, and Atlantic, fantastic, and we’re not even talking about Tamla or Stax – genius! And what did we have over here? Parlophone and The Beatles. Big deal. Overstayed their welcome. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a bit of a Beatles fan, but you never need to play them again!

When Andy Bell [formerly of Ride] joined Oasis, I was doing a session with him down the road in Waterloo. It was a Friday morning and we were doing these shots, and I goes, "Andy, fuck that, I’m glad you joined the band. Get these wankers off The Beatles and teach ‘em about real music, will ya? Get your blinkers off chaps." Weller always had the UK influence with The Kinks, The Beatles, whoever, but also his influences were slightly wider, because he had the soul thing going on as well.

But the Oasis boys – it just seemed like tunnel vision toward The Beatles and all that tosh. Genuflect at the altar of the Fab Four if you will, but there was so much more about at that time. You don’t actually have to listen only to them. There were other things quite worthy and probably better.

And somehow you ended up at CBS Records as a staff photographer…

TS: I was fed up reading the music papers. I was just looking at anything that came from America, or at the folk pages to see when Bert Jansch was playing next. The UK music press wasn’t writing about bands that I wanted to read about; if they had something on the Flying Burrito Brothers, it was only half a page. So I started buying the fanzines, like Zigzag. I got to be friends with John Tobler and Pete Frame, and Tobler was working in the press office at CBS, and he was starting up a photographic department. There were lots of people in London chomping at the bit to get a job like that.

I’d always counted myself lucky. Getting to know Tobler and Frame was great; when I’d come down to London and visit Tobler, I’d go back up with a load of records. And then working for a record company meant having access to an unrivalled amount of vinyl, and I still haven’t lost that kind of thirst. It was a case of right time right place and knowing someone, cos I was pretty inexperienced. While I was living in Sheffield I was photographing bands that were playing at the City Hall, where I saw Captain Beefheart, and took a nice live picture of him and thought, yeah, I can do this.

I had always wanted do something like that, but I’d left school at 16 years of age, and you had to have a City And Guilds, some sort of qualification to be a photographer. Not being a particularly outgoing person, I was kind of hemmed in by my own self-imposed restrictions. But then I just thought, "I’ll have a bash at that, not everybody’s an arse, let’s get on with it."

The Clash – ‘Rock the Casbah’

You worked with The Clash at CBS, but I get the feeling punk wasn’t a life-changer for you.

TS: It was a bit too much noise without a lot of content. Loads of blokes shouting. Of course there’s more to it than that, and there’s some good songs that have come out of it, but by Christ, they’re few and far between. I’m sure I’ll get it in the neck from a lot of me mates, and I understand that it was a statement, but it wasn’t for me. Even though I was probably only two years older than Joe Strummer. But I was not going to overnight change the way I dressed, just to be a bloody punk, and start shouting me head off. [Laughs] I just thought it was a lot of tosheroo, actually.

I never saw the Pistols. I liked the devilment of it, but I didn’t like the aggression and the blokeyness of it. If you hear a Pistols record now, you do find a melody, but at the time I didn’t; it wasn’t for me. I didn’t want any part of it. It just seemed like a bloody racket. American punk music seemed to be more melodic. I know it was a little bit later, but the Modern Lovers – fantastic record. Television. Fantastic record.

The Clash were into all that devilment, too, and it gets to be a bit boring. They were always acting in public, like all those bands. Always a bit lairy. Part of the schtick. It wasn’t directed at me, but because I wasn’t in the uniform, I was probably the enemy. But when you see some of their mates, they looked like eejits, and they weren’t wearing the uniform either. Yeah, I was a hippy, and still am to a degree, so I’m told.

Chris Bell – ‘I Am The Cosmos’

I remember sharing an enthusiasm for Big Star with you in our Melody Maker days, and hearing that you’d known Chris Bell.

TS: That’s while I was at CBS. His brother David was over trying to get him a deal for the album that would be I Am The Cosmos. He’d come to see John Tobler, who was head of press at CBS at the time, and we’d go out for lunch. Sometimes JT’s expense account would take us to nice Soho Italian restaurants, and other times we’d go to the Bierkeller in Soho Square, which is now that Hare Krishna place. Often we’d go to the Pillars of Hercules in Greek Street. Chris was a bit amazed at the way English people drank at lunchtime, and pubs closed at 3 o’clock. God knows if the lad were alive now, god rest his soul, with all day opening, his eyes would roll.

He was just really charming. He and his brother would come up to Soho Square and Dave would go up and talk to Tobler, and Chris would come to my studio nearby. (I say studio, but it was just a large room.) My assistant would be printing, and Chris and I would be listening to some records. Honestly, I’m such a fool – I had cameras and rolls of background paper there and he’d sitting there in a green Nudie suit. We’d be talking about a Pure Prairie League record, and I wouldn’t dream of taking any pictures, because I was a fucking idiot. The only pictures I took of him were part of a roll of black and white for a guy called Bert Muirhead who interviewed him for his fanzine called Hot Wacks. Some pictures exist; I should have taken more. But you feel like, if you haven’t got the gig to do it, then you don’t want to get on people’s nerves. I never do things on spec. If there isn’t a reason to do it, don’t do it.

I never forget what [music writer] Brian Case said to me. It might have been 1978, and we were standing outside of a pub on Dean Street, maybe the Crown and Two Chairmen. We were talking and Brian said to me, you’ll never have a friend who’s a musician.

Cruel but true?

TS: Yeah, they’re all too self-centred, aren’t they? The bastards! [LAUGHS]. I’ve always carried that with me. He’s probably right, actually. I don’t like to think it, because I like to think that most people are pretty genuine. But they are different from us, because all they’ve got to do is twang a few strings and sing a few words and we’re crying our eyes out. But I think they all are, in the best way, self-centred or whatever. Love ‘em to death, but… I wouldn’t rely on them to save your life. The rest of us are all just a spoke in the wheel.

In interview situations typically photographers get the shitty end of the stick time-wise, but on the other hand bands tend to like photographers more than they do music writers.

TS: True. Because journalists… well, never mind when you give someone a black review, but just a light grey review, and it’s "Argh, did you see what they fucking said?" With photos, though you’re not going to run a dodgy picture of someone, cos it’s got your name on it. You’re always going to go for the best shot.

As for opinions about music, I remember shooting The Charlatans in Bristol, in my first encounter with them, and then a few more times. The first album was out, the second album came out, and I went to do something with them, and I’m in the dressing room, and Tim Burgess said, "What do you think of the new record?" And I said, "You’ll have to try harder mate."

I’d struggle to be that blunt with someone I admired in their dressing room.

TS: Well it wasn’t as good as it could have been, it’s that simple. I think it needed to be said. You know. I wasn’t under the influence or anything. It’s because I thought they were a great band, at the time when they started, and I thought they could be better.

The Charlatans – ‘North Country Boy’

When I told fellow writer Pete Paphides I was talking to you, he told me that the really interesting Tom Sheehan story is the part you played in so many British musicians’ musical education. Your love of American artists – the Grateful Dead, Big Star, Bob Dylan, Gram Parsons, Neil Young, Moby Grape – has rubbed off on countless people, thanks especially to the compilation CDs and cassettes you’ve pressed on so many artists. I couldn’t help but think of this track.

TS: Tim [Burgess] was already a Dylan fan first time round when the first record was out. And obviously I took a lot of stuff to his table, to their table. Of course I was viewed with maxi suspicion by people from the Black Country – Martin [Blunt] and Rob [Collins] and [Jon] Brookesy. [Laughs]

But in return I think I got a lot of stuff from Tim that I’d never heard before and love to this day. So it’s a mutual thing. It’s strange, though, that a lot of the time, musicians aren’t particularly fans of music, are they? I can’t believe it. I can talk to people young and old about music I love. Because by the time I was 16, I was lucky enough to have already heard R&B stuff played to me, Merseybeat, the beat boom, American stuff, soul music. And when I started work, in the very first week someone lent me four albums. I thought what a tremendous thing that was to do for someone, and I’ve always gone about it the same way.

You can talk to a musician and say, Have you heard so and so? Cos you sound a bit like them. And they say no, so you aim some stuff at them. And you meet them two years down the line and they agree, what a great record. Because you know, you can’t know everything. And as we know, there are a lot of journalists, photographers, PRs, people generally, who are snobbish about music, and I’m not.

I think if you’ve got a fire about something, you’ve got to tell as many people as possible to share that fire. And people do it to me and I do it to them – and it’s great, I love it. That’s the joy of it – to share the tunes.

When did you start making your famous compilations?

TS: Oh, way back in the cassette days. I can pinpoint a time – me and the Studs [Melody Maker’s tag-team journalist provocateurs The Stud Brothers] had gone up to the Hacienda to do Primal Scream for Screamadelica. And the second session was in Click Studios in Clerkenwell in Great Sutton Street, and I thought, well, I’m shooting Bob [Bobby Gillespie], I’ll take him some stuff that I know he’ll like. And I took him Gene Clark’s No Other, and – what’s the Stones record with the cake on the cover? Let It Bleed. And the third Little Feat album, Sailing Shoes. Play some tunes, get some beer in, a glass of wine, take some snaps.

So I was playing these records in the studio, big speakers on the wall, big empty room, one backdrop, and there we are having a chat. And I put on Little Feat, ‘Trouble’, third track. And Bob says, "Ah Tom, this is great, this is great." And I go, "Alright, I’ll knock you up a tape."

A year goes by, and I’m at a bash, and Bob’s there, and I say, what do you think of the Feat, and he goes, "I only like the track you played me man, I didn’t quite get it, didn’t quite get it at all. But I loved that track." And I went, "Oh, ok." About another two years go by and we meet up and he goes, "I was wrong, I was wrong!"

And, well, that’s it. It’s impossible, through someone’s enthusiasm or just having it passed on to you, to get it all at once. The penny drops two years down the line when you’re not even listening to it, you’ll think of the melody – and wonder, what was that, and bang you’ll find the record and think, why did I ignore you so long? And you end up loving that record and shouting your head off to anyone that would listen to you about it. That’s it.

Did you ever meet a blank wall?

TS: Not really. When Ride did Carnival Of Light, I spent time with them at Sawmills, RAK, Abbey Road, wherever else they were. John Leckie was producing it, an old chum. When they brought out the first track, Pricey [Simon Price, Melody Maker writer] was doing the singles and he said something like, "Oh, well, Ride, one-time great band, but they’ve listened too much to the second most evil man in pop, Tom Sheehan, who gives these people Gram Parsons records to listen to. And the first most evil man is Alan McGee for signing them." [LAUGHS] For fuck’s sake Pricey you bloody idiot, it’s just tunes, mate.

But there’s a reason why so many people are tribal about music, because it’s in essence saying, I like this kind of thing, because that’s who I am, but I don’t like that. You can see the appeal.

TS: Yes, if you’re twelve! [LAUGHS]

Manic Street Preachers – ‘No Surface All Feeling’

You’ve had no shortage of sessions with the likes of Weller, but you’ve told me there are people you wished you’d shot more. Hence this song.

TS: Bob Dylan is the person I wished I’d photographed, and I never have. There have been some great pictures, and he’s worked with great photographers. But I think if he’d allowed them to do more, there’d have been some better ones. The whole thing, isn’t it, is trust from the person you’re photographing, and letting them understand that they should understand what you’re there for. You’re not on holiday. You’re there to nail it.

Famously sometimes you would have just a few minutes to shoot bands, be it because of tight schedules or prima-donnaism. You’re famous for your ‘get in, get out’ approach: did you always have it?

TS: No, it was foisted upon me. Because you don’t know how long you’re going to get. You cut the cloth accordingly. How much time have we got? We haven’t. Oh, ok. Bang bang bang. You just have to make up your mind to shoot how you want to do it in the space of time you’ve got and be happy with what you’ve got.

And do you get better pictures that way?

TS: For me. People might not like ‘em. There are always the people who say, "Well, couldn’t you get ‘em to just…" But they’re not fucking performing animals, they’re musicians. Obviously there are musicians that horse around or whatever. But it’s not for me to make ‘em do it. If they do throw a shape and you get it, great. And if their schtick is to leap through a hoop of fire, great, I’ll shoot it, but I wouldn’t set up a hoop of fire and ask them to do it. You know, photographing Ozzy [Osbourne] pissing on the Alamo wasn’t my idea. "I tell you what, you have a piss on the Alamo, Oz, and I’ll take a picture of it." No, no thanks.

Was it a wrench moving to digital?

TS: I think I made more of a wrench of it for myself than it needed to be. I loved shooting on different kind of emulsions, different kind of films, different format, different cameras, different lenses, you know. Whereas now, it’s predominantly just one camera, one lens, and you do it all later. But I love it. I can sit on my Mac, do a shot, get rid of all the spots and all that, and then do some copies and treat it different ways.

So you don’t pine for the darkroom.

TS: No. I’m moving with the times. I don’t mind. I’m sure in recording studios when they went to ProTools, it took a while to get used to that, but I’m sure once they did, it became just another tool. I wouldn’t want to go and shoot film. I’ve got a darkroom at home but I wouldn’t want to spend hours in it any more. I’ve already spent years in one.

You told me you wished you’d taken more photos of Richey Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers.

TS: He was a really really nice guy. I’d shot them a couple of times, and they were doing their album sleeve and I’d photographed all those pictures of European flags on fire. Did ‘em over in Clerkenwell on a Saturday afternoon, me and Rich chatting and all that, and then they had this idea for the front cover of the album – well, the record company did, I wasn’t privy to it – but they had a shot that didn’t work. So had this idea of just shooting Rich’s tattoo and just changing the tattoo from whatever it said [Useless Generation] to Generation Terrorists, with the cross on it, and I ended up shooting that. It was winter. He had his shirt off. He had the flu, poor lad.

He was a lovely guy. When they were supporting Suede, in Paris, me and the Price Cube [Simon Price] went over there, and Richey wasn’t in great shape. You know what I mean. He was ok, but not in great shape. So we’re all kind of arm’s length and after soundcheck, James [Dean Bradfield] came over and said, "Richey wants to know if you want to go on the bus and have a couple of beers and some tunes", whatever. And we were putting on Neil Young and Gram Parsons records and all that. And Nick [Nicky Wire] was going, "This is all your fault, Sheehan, this all your fucking fault." So I said, "Open your ears, you deaf bastard."

And then after Richey went missing, I was at the wedding of Martin Carr from the Boos – Buzz Lightweight as we called him – and I did the snaps. (I won’t do another one – I’ve done loads of weddings and I fucking hate them. Too nerve-racking.) They had a bash over at a pub near the old Creation office. And we’re in there jollying up, and 18 Wheeler were DJing. They were loading in the decks and putting the records out and on the top of one of the stacks was the Flying Burrito Bros’ Gilded Palace Of Sin. James from the Manics was there, and I pointed to it and said, "Oh, a proper record. Do you remember that time on the bus? Richey asked us on for a beer and a chat and I put that on." And James said, "Yes, I do. It was probably your fault that he fucked off!" He was joking, you understand. But there you have it – "It was your fault he fucked off!"

They were a band for whom visuals were very important.

TS: Definitely. It was rehashed, obviously, from all the Clash stuff and all that. But at that point in time they were channelling their influences. You know it’s like any musician or artist; you gotta get all that out of your system before you find yourself. If you’re a painter and you’re influenced by Matisse, you’re going to paint like that until you go through it and find yourself. And it’s the same with any creative force. You’ve just got to get it out of your system.

What about the power of those images for fans?

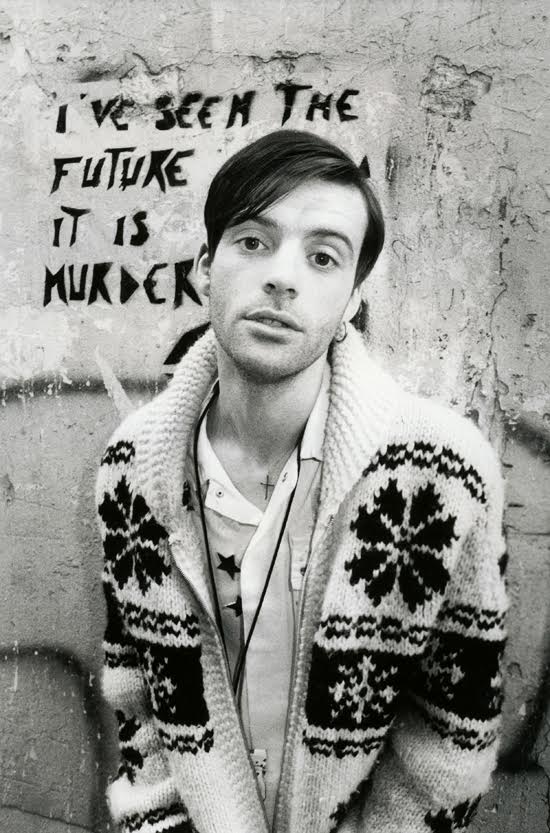

TS: The unfortunate thing for someone like Rich, certainly from the Paris trip, is that Price Cube was a student there, so he knew the area like the back of his hand. And he took us down the catacombs and we did some pictures against the skulls and all that. And it’s quite powerful. [Fellow photographer] Kevin Cummins said, "I wish I’d taken those pictures", and I said, "Well I wish I’d done one of the pictures you took." And there’s that other picture we took outside the club in Paris that night, that one that was bloody bombed, and there’s that stencil on the wall, "I’ve seen the future and it’s murder."

And you go, these are great graphics, and great for shots. But you don’t know what’s coming down the line and you don’t know that that picture of Rich in the catacombs with all the skulls will have people thinking too much into it. No, we just happened to be there! If it was a pie and mash shop down Walworth road, would someone be thinking about that?

You don’t do it for any spooky reason or something that might happen in a few years. You just do it. You’re there. It’s an interesting image for that week. Obviously when I was looking at Rolling Stone magazine when it first come to the UK, looking at all those photographers and looking at their work, I was thinking, "Brilliant, this is what I’d love to do." You do realise eventually that you’re creating some sort of rock history. You’re just there documenting – and making something that may have a life longer than that group’s record at that point in time, hopefully. Sure, I like the idea that I am part of the history, without shooting me mouth off about it all. That said, I may not be shooting me mouth off, but I’ll be sitting signing a bunch of copies of Aim High in a couple of weeks’ time…

Snoop Dogg – ‘Gin & Juice’

I know there’s a pretty good story behind your famous “black power” shots of Snoop Dogg.

TS: Very strange actually. We went over there to LA do him and we arrived on Thursday. We sat by the phone all week. Cancelled, cancelled, cancelled. So on the Monday, we’re leaving at 4 in the afternoon, and we ended up going round there at about 10:30 in the morning, after being there since Thursday. At the time, there was some story about his being connected to someone being murdered or being shot, and we weren’t allowed to mention the fact that he was possibly an accessory to murder. It would definitely be good form, we were told, if we didn’t mention it whatsoever. But in the cab on the way over, we were going past this joke shop and I asked the cab to pull up and I bought a pair of joke handcuffs.

Was this your idea of a low-key prop?

TS: Well, you’ve got to have a rough idea. [LAUGHS]. Sometimes you do it cos it’s the challenge, right? To cut a long story short, we go round to his place, we find him staying, while his house is being built, in a house in this kind of gated community. Which is intriguing in a way because he’s gone from one ghetto, where they’ve got nothing, to this ghetto where there’s loads of money. So they’ve been on the razz all weekend by the looks of it, and there’s the smell of Bob Hope everywhere. Some little kid rapper is rapping away, couldn’t have been 12 years old.

So Snoop ain’t too up for it, but he’s being accommodating. He’s got a party going on, end of a party, loads and loads of people there. So we go down in garage downstairs and we do some shots in there, and then we go out into the public area. And I said to him, you know in the Olympics when Smith and the other guy did the power salute, could you do that? He went yeah. And I said, alright if I just clip these on? And I got him doing the power salute with the cuffs on. And I just took about ten shots on the motor drive. And a couple of colour frames.

There was some steps with these bars, and I said, just sit on these steps. I went round the other side and he’s looking through these bars, and he’s got his hands on the bars, and I shot him like that. So I didn’t actually mention it, but I ended up with graphics that would go well with that kind of story. So I went back to the UK, after waiting four days, quite happy.

You’ve gotta throw yourself in as bait basically. And all those rappers – and I’ve done Chuck D, him, Ice Cube, Ice T, all those – they’ll throw a shape but only on their own terms. So you’ve got to get in there and, purely as an exercise, get in there and just tip it over one way or t’other.

To generalise, are there any kinds of people that you shoot that are more mistrustful, more unbending?

TS: Generalising, I would say it’s young people and seasoned people. People in the middle are fine. When they’re old they’re like, "Ugh, god, I don’t look right, cos I’m not in me prime." And when they’re young they’re sort of like, "Yeah, they’re the press and we’re cocky and you can fuck off." That’s what it was like doing the Stone Roses. They’re down in London and they’ve got all these Lionels, big flares, on and all that. And they’re giving it the old fucking attitude, cockney this and cockney that, and I’m like, "Shut up you twat, you’re wearing fucking Lionel Blairs and they went out in the Sixties!" And Reni goes, "You heard our record?" "Yeah." And he says, "What do you like about it?" So I went, "Well, the one about the waterfall’s alright."

Is it ever a staring contest?

TS: Kind of. I know what I’ve got to do. If they know what they’ve gotta do, you get married and that’s brilliant. I love a bit of banter as well. And it’s always from the Northern bands, you know, the Manc bands, like the Mondays. And that’s why I started talking in cockney rhyming slang, just to piss them off. Cos they’d be going ‘extra man’ and ‘banging’ and all this. Get out of it you twat. So I start going, drop your Gunga Din [chin] a bit.

It’s like when we did the Mondays for the Maker, we just wanted Shaun and Bez. It was at Holborn studios in Back Hill in Farringdon on a Monday morning. And all of them were there, about 12 of them. And they were like, "You got any speed?" Got any speed? It’s 11 o’clock on a Monday morning, mate. So I said, "I tell you what, why don’t you lot go into the canteen, and have a breakfast, have a beer and whatever, and I’ll sort it out." And they said, "We’ll just have beers." So I’m doing Shaun and Bez, and the phone goes from the canteen: "Tommy, Bev from the canteen here. I got that group of yours in there. They’re drinking all the beer. They’re up to 48 quid! Is that alright?" And I went, "Yeah, stop them at 50."

REM – ‘Turn You Inside Out’

When I asked you who always delivers as a subject, Michael Stipe got your vote.

TS: He’s someone who can always turn it, right from when he started, and when he comes out with a solo record I’m sure he still will. He just knows what to do. It’s as simple as that, in the sense that he’s someone who understands photography. Someone who knows how they’re going to look; who looks at the camera you’re using and understands that the lens you’ve got on is going to make them look a certain way.

And then there’s the other kind. Lou Reed, who I never was much of a fan of, is there – and he was famous for it – wasting your fucking time. He’s going, "Hey, you know you look like? A friend of mine who runs a pool hall in the Bronx." "Oh really?" I go, "Who’s shaving this pig? I’ve got ten minutes. We can talk later if you need to." You gotta stop him.

Stipe is a pleasure to shoot. You put a camera in front of him… he doesn’t actually pose as such but there’s always something there that’s beguiling, just as he is a beguiling performer onstage. He knows exactly what to do without actually doing anything. Which is a tremendous gift. But with a lot of American bands, they don’t understand the British magazine take on photography. And I always say to them, you know in England we send ours to RADA, the drama college, so they learn how to pose and throw a few shapes – got anything like that in America? Nope? Ok, so what are you going to do?

What about in 2016, with everything digital technology has to offer a photographer and his subjects?

TS: What it’s doing is just shoving it further into the corner of having everything done up to perfection, which as we all know isn’t that great. You’ve got to have a few rough edges to make anything work. And that’s why you’ve got these high end photographers using high end equipment, going into post-production, and the results look like medical experiments half the time. The thing is, digital’s so unforgiving on a face, even if you’re not shooting on an expensive camera. You see everything and that is terrible. So you’ve got to spend hours taking blotches out and all that.

It’s surely even scarier now to have your picture taken than it once was.

TS: It certainly is. I don’t like it too much. But there again musicians are in an industry that requires them to do these things. And then the record companies will make sure that the images they get for press and promotion are those ones that are sadly overworked. And they could look like works of art, but they’re so far removed from photography as I know it.

Obviously you can pick and choose who you work with.

TS: I just wish the phone would ring a bit more often. [Laughs]

Is your job dying?

TS: It probably is, for various reasons. And personally I’m a pensioner; I’m 66 years of age.

Tom Sheehan, Sanderstead, 2016, by Alex Sheehan

Are you sad that the print music press is dwindling?

TS: Absolutely. I used to love the fact that you’d be looking forward to seeing Sounds on the stand, Record Mirror and obviously the NME and certainly the Maker. And you’d be at Tottenham Court Road tube station and you’d come out and, from the other side of the road, you’d see your cover, and if you could see it from that far away, you’d think, "I won", yeah I won that week.

I still get a kick of out of seeing my stuff printed. You know, people who are younger and want to be like us can do a bloody course at university, but where the fuck are they going to go?

Radiohead – ‘The National Anthem’

I wonder if you feel you’ve had an insight into performers’ anxieties, about not just their images but their jobs, and especially those who you’ve photographed a lot.

TS: It can be palpable sometimes for all sorts of reasons. When Radiohead signed to EMI, I did a session with them, cos I had already done a couple for the Maker and I got wheeled in. They weren’t going to be dressed by a stylist, so instead EMI had given them some money to get clobber. So Cos [Colin Greenwood] went out and spent it all on a Paul Smith suit that he continued to wear for the next three years – value for money. A few of the chaps bought shirts, jeans, trainers or whatever.

And Thom, he’d got some clobber as well, but he was a bit annoyed, because I think the grief on the day was, "It’s like we’re a corporate rock band, wearing new clothes for the sake of having some pictures taken." And he was right. And he wasn’t into it.

So I said, "Well, let’s go for a curry." And he said no, no, he’d be alright, it wasn’t wearing him down. I said, "It doesn’t matter if we knock it on the head today. We’ll do it whenever we want to do it." So we went out for a walk, took some pictures, came back, did some more pictures. And then ended up doing another session for the LP. It was never going to be a group shot on the cover anyway. You can see that anxiety where someone is battling someone else’s idea, where the record company wanted them to dress up.

They’ve never been clothes horses; and now they’re forty-plus years of age and they still dress like students. But smartly dressed ones. Their visual persona is their own, one they’ve created for themselves, not had shoved on them.

Thom’s eye must be something you thought about as a photographer.

TS: When they started, NME did a terrible, terrible thing in Thrills, running pictures to say how ugly he was. It was just fucking terrible. It’s not funny, clever clogs, and it’s a personal attack – on a person who’s going to change a lot of people’s lives. But for all that, seeing him [in photographs] was great; it opened up the gate. If there’s someone else like him out there, then they’re gonna go, Jesus, this guy’s on Top Of The Pops, so what have I got to worry about? I’m not the only one.

Maybe musicians’ anxiety about photo shoots with professional photographers is small potatoes in an age when every concertgoer has a cameraphone.

TS: The thing I can’t get over is people wanting to take a picture at a gig when they’re stuck on a balcony somewhere, and they’re all up there waving their phone. Do you actually like music? Why are you here? Might as well just get a video.

Paul Weller – ‘I’m Where I Should Be’

I reckoned we should close with something from Saturn’s Pattern, so I’ve picked this one for the sentiment – “I’m where I should be”.

TS: Oh, so now you’re writing the story for me now – you’re putting words in my mouth. [LAUGHS]

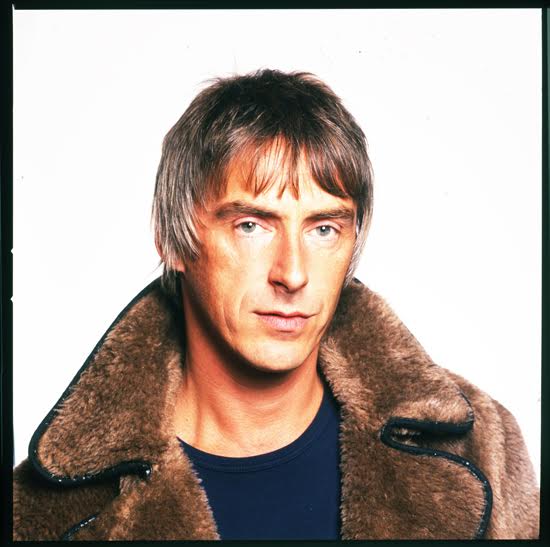

I’d say I chose it because it’s graceful and gorgeous, and of the hope in the lyric – “I leave it up to fate” – and I because I hoped that when Paul looked at all your pictures of him in Aim High, from smooth-faced youth to middle-aged man, it wouldn’t feel like the journey was about loss of youth, but the gaining of wisdom.

TS: Well, when I thought about doing the book, I was supposed to ask him over Christmas, but I thought that would be a terrible thing to do, so I decided I’d wait until the new year. So I just texted him and said, I want a word in your Donald.

That’d be the rhyming slang again.

TS: Donald Peers, ears, yeah. And he rang us back in about ten minutes and heard me out and said, "Yeah, yeah, good idea." That’s when we started talking about age and all that. He’s cleaned up his act a bit, he doesn’t drink any more. Still smokes, and that probably can’t do you too much good. But you know, he still turns himself out well. Obviously he’s 58 years old, and you’re not going to look like you did when you’re 22. And he realises that, but he’s still making music.

Do you think he’s happy?

TS: I think he’s always got something to prove, which is why he keeps going. Like a lot of people who won’t be happy with their previous work, they’ve got to move on. That’s the mark of a true artist to a certain extent, isn’t it? You don’t stop, still got to move on. Still got something to say. A lot of bands run out of steam after a while and they break up for all sorts of reasons, but predominantly it’s probably one in which the creative juices have stopped flowing. And that’s the terrible thing – I think we’ll all rue that day and hope that never happens. If you’re not interested in doing your job, what are you going to do? Shuffle off somewhere I suppose.

He’s still a good-looking chap, as you can see from at the current picture, the black and white shot on the slipcase.

TS: [Laughs] “Twelve years ago.”

Ah, the old joke – if you don’t like this picture, put it in a drawer and look at it five years from now. I’d argue that he now looks much more interesting than the smooth-faced kid in The Jam or the Style Council. Do you think it’s hard for even the most robust-egoed frontperson to look at any random snap of themselves from back in the day, and compare it to even the best picture today?

TS: I‘d imagine that most people kind of get their heads around it. You’d be foolish to assume that you’re going to have the same glow that you had as that newborn form, as that kid when you made your first album. You are going eventually going to look like an old saggy old boot. But I think that’s quite nice. At least they’re still around to make music.

Do you find beauty in those weathered faces?

TS: Not beauty in its strict sense. But I like the idea that people keep on doing what they’re doing.

Maybe then you could argue that we don’t need you taking a picture of any of them, all old and wrinkly.

TS: [SHRUGS] I don’t know. It’s true that not many mags are going to run ‘em – if Mojo do a feature on whoever, they’re not going to do a session with the artist now, they’re going to take one from back in the day.

But I think people should be brave and not be so vain. Obviously they have a past. We all have pasts, and we all looked better than we do today or we will next week. But the most important thing is the music. It don’t matter if you’re wearing a fucking boiler suit and you’re 12 or 112. It’s the music that’s the most important thing, I figure.

AIM HIGH: Paul Weller in Photographs 1978-2015

By Tom Sheehan is out now via Flood Gallery Publishing.

Deluxe (limited edition of 2,500) and Super Deluxe (limited edition of 500), available via Pledge Music. Launch party May 26, 7pm, The Flood Gallery