It’s a blustery mid-February Wednesday afternoon in Old Montréal. Businessmen in thick-rimmed glasses whisk past fashionistas in vastly more expensive thick-rimmed glasses, on their way to or from lunch meetings, speaking quickly in Franglais, and carefully avoiding the puddles of slushy snow that dot the cobblestone sidewalks. I’m stood just outside the unassuming brick building that houses Tim Hecker’s new studio space, watching the flurry of bilingual activity unfold and thinking that just upstairs the resonance that’s being generated could probably crush their BMWs into piles of double-parked debris. Right on time, the unmarked door swings open. “Where do you want to go for lunch, dude?”

As a fellow Ph.D. student in the communications studies department, I met Hecker a while ago, having been hired by McGill University as the teaching assistant for a course on sound studies that he’d be leading. His compositions were a staple on my stereo for years prior, so I was looking forward to working together. We bonded over a shared love of music, beer, hockey, and a certain bent and cynical worldview. After our last class, we headed to the local bar and, on his iPhone, he played me a few tracks from Dropped Pianos. Even over tinny mobile speakers, I could hear the shimmering, melancholic beauty of music beyond the vanguard of an art form. The jury’s still out on whether or not the undergrads in that class gleaned anything from our lectures, but I felt that’d we’d sufficiently shaken them out of late adolescence, and encouraged them toward hearing with a more critical ear. And it was just as much a learning experience for us as it was supposed to be for them.

We walk briskly to a fancy lunch counter, and pick up some salads and next-level chocolate bars to go. Hecker tells me about the recent recordings he and Ben Frost have made, and some upcoming collaborative projects he’s looking forward to. But mostly, our conversation revolves around how we’re going to proceed with this interview. I get the sense that he’s not wild about it, as he rattles off a litany of questionable questions he’s been asked over the years. (I immediately start hitting the delete button in my mind.)

We head back up to the studio and eat, listening to some new recordings from his most recent trip to Iceland. I’m stunned by the latest sounds emerging from his studio monitors, as Hecker scrubs back and forth over what seem like endless files onscreen. The music is more rhythmic than I was anticipating, but blossoms with the unmistakable flourishes of dense and percolating distortion that have become his hallmark.

“It’s awesome,” I say.

“You think? We’ve got two more sessions booked after this.”

I’d be glad to sit there and listen all day. But after another lengthy discussion about how creativity and the flow of ideas die as soon as an interviewer starts asking questions, I start asking questions.

You’ve been at it for well over a decade, producing consistently solid work. Why now? Is there something in the air that makes this moment particularly ripe for you?

Tim Hecker: Not sure. I think it’s just minor successes, like a little bit of luck and a little bit of perseverance and a little bit of doing good work. It’s always a combination of those kinds of things. You can’t really plan. I don’t feel like I had any dues that needed to be repaid or anything, or my time was coming. I think that stuff is kind of hyperbole or something. I’m glad the record [last year’s Ravedeath, 1972 was successful, and I’m glad that a large amount of people found a connection with it, for sure.

You’ve just come off a tour of Europe. How was that?

TH: That was great. I mean, some really amazing concerts, and half of them were organ-based. It’s treated organ and it’s largely electronics, but I do try to blend the organ, given the constraints from the space with the PA and that, so that sort of determines how loud I can play the organ. A lot of these concerts have been super fun, and I have been playing pretty loud on the last tour. Louder than normal.

Nice. How did you prepare the organs?

TH: It’s a kind of system that relies upon a lot of sounds generated internally through my computer and mixed and effected, and I take microphones, a couple microphones on the pipe organ itself, and run that through my electronic setup and treat it. It comes out of both bass amplifiers, and hopefully a supple PA system in the room itself. So what you hear is mostly the PA, but there’s a blend of organ depending on how intense the sound levels are.

Did you enjoy turning the album into a piece for performance?

TH: I try not to contextualize it as ‘playing the album’ or anything like that. It’s a chance to riff on similar material in a different way, and I take a few of the pieces and kind of stretch them out and pummel them and reconfigure them and distort them even more, and find different phrases to circulate on.

What do you dig about playing in churches?

TH: It’s a mixed bag, because it’s a chance to play a great space that people associate with spiritual or transcendental states. But I’m not really someone that attempts to promise that kind of same mindframe, as in, you take the religion out of the music and you can still achieve that kind of promise of deities or whatever. I think that it’s often used as a… Sometimes it’s a fraught, kind of laden world of performance that I think can be really dubious, but it’s also super fun to almost desecrate an instrument that for 500 years has been associated with God. But prior to that, it was not at all. It was a deeply secular musical instrument.

Does ‘rave’ have anything to do with religious rapture?

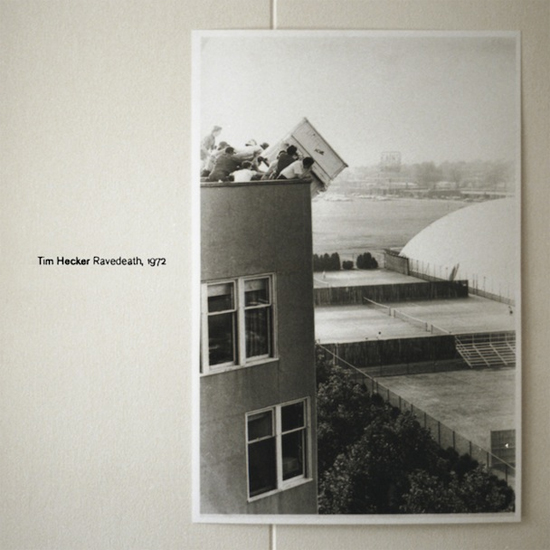

TH: I’m not sure. The title itself was written late at night in an iTunes information panel when I was doing demo mp3s, and it was almost like a Ouija board form of automatic writing that just happened in the field. The title I just wrote down as a joke almost, and it kind of stuck. I think it started from some imagery I’d seen of a rave disaster in L.A. where 30,000 people crashed a fence, and there were candy ravers with blood all over their faces. Something like that. It’s not at all related to the imagery of the album, but there’s some sort of collusion that didn’t make sense and made perfect sense at the same time.

A lot of people claim to have religious or transcendental experiences listening to your music. Is there any way you prepare yourself for getting into the practice of music-making, or do you just crack your knuckles and give’r?

TH: Studio work is a kind of mix of dull, bludgeoning, plodding, getting-nowhere feelings of hitting your head against the wall, mixed with these amazingly crystallized moments of epiphany and revelation and vision. You never know when those things are going to happen. I personally can’t find a process where I can trigger that state of finding that kind of magic. Because if it was so easy then it’d be preset-based – and if it’s preset-based then it could be done very easily by anybody. [But] it’s something that really comes with hard work and labour and time and patience, and being open to your music spiraling off on different tangents and going with it, and not being sentimental about music that’s not quite there. Just destroying it.

Your free gig a few months ago here at the Musée d’Art Contemporain was in a black box, with the space completely flooded in fog. It was bone-shatteringly loud, and rather claustrophobic. Had you planned on it being something like a sensory deprivation tank?

TH: For sure. All my concerts are like that, by the very nature of mandating low-to-no lighting. Because I refuse to perform my music in a traditional sense of instrumentation, I don’t have an amazing live stage spectacle to provide, and I don’t want to go there. I don’t see how the music would stay true to the spirit of the work. So working with devices and guitar pedals and mixers and synthesizers is what I do, and I prefer people not focus on that because it’s kind of distracting from what the point should be. At least for me, it’s to have the primacy of aurality in the experience of that evening. I try to deny the visual aspect as much as possible. That’s what I do right now. I’ve worked with video artists and sometimes it’s really amazing. I’m doing something in May which will be like a live re-score or live improvisation to an old Herzog piece. I’m still up for doing that stuff, but I find that I enjoy darkness more than anything.

How do you think album art affects the experience of the listener? Is there something lost when people have nothing physical to look at and hold?

TH: I would say yes. Album art’s a major part of it, despite talking about the dissolved commodity and the digital, invisible nature of music. People still attach very much to a visual representation in terms of what that is, in terms of the album art. Also, it’s one of the first things people slam. When they see it, it’s like ‘how crap that looks’ or whatever. It’s kind of ironic and weird, but it’s something that I take as an opportunity to have fun with and do really seriously. So be it.

Are there ideal media or listening conditions for you?

TH: I love vinyl, but I’m not a ‘vinyl person’. I still collect, but most of my stuff is digital right now. I work in the long form listening experience right now, so there are structural constraints with doing vinyl, and you have to make rough decisions with sequencing and work within the limitations of having good audio for 15 minutes on a vinyl side. I love doing it, and I love how it sounds, but I’m like a – not digital apologist, but I work very much in modern sound and I listen to my demos with mp3s. Vinyl’s just a fun endgame step. I work with analogue signal chains too, but the mp3 is the way I listen to music.

With all the discussion surrounding SOPA and PIPA in the US, the fall of Megaupload and other file sharing sites, and bill C-11 essentially destined to become law in Canada, how do you feel about the proliferation of music online?

TH: Yeah, like going back to that Kim Jong… What’s his name again?

Dotcom.

TH: Yeah, people conflated SOPA with the shut down of Megaupload, which was actually based on previous basic legislation and a bunch of other violations. I’ve used it like anybody else, but at the same time, seeing pictures of how that guy lived his life? Like a disgusting, gluttonous person on the backs of digital content providers who were making little to nothing off that, and him basically selling the rights to his infrastructure to pilfer free digital content that most artists wouldn’t have wanted free, or wished they could get compensation for? I mean, I have to be able to pay for compressors to do my music to make it sound good. If there’s not a reward system, there’s less of an incentive to work at a certain level of quality, maybe? Obviously, a lot of that stuff is being undermined by plug-ins and things like that, and it’s being leveled.

Are you flattered or offended when your music pops up for free?

TH: It’s both. I’m not an anti-online person. I get what the modern world’s about and I understand that that’s the nature of music dissemination. I’m not a nostalgic person for the glory days of 8-track sales at the local K-Mart. But there’s a little bit of flattery and a little bit of horror. It’s a mixture. It’s like sublime shock and awe, but also terror. That’s always the way I feel about how music flows through those types of networks. I’m mostly cool with it, but I definitely appreciate when people support the work.

Do you think music circulating online makes people care less or more about music? Or care in a different way?

TH: There have always been people making music. On their porches, playing folk songs. Playing piano in quiet salons. You don’t have to listen to every MySpace page, so what’s the difference? It’s just noise that you filter out. And naturally, there are systems of aggregation and taste-making that are themselves being redefined. Part of why I found a connection with the picture of people throwing a piano off the building was that these were engineering students, some of them working in the emerging computer fields in the 70s. And MIT was a place where early forms of the mp3 codec were developed. So there’s a relationship there that’s kind of ironic. I guess that sort of summarizes how I feel about it. Like, super ambivalent. I’m ok with it. I download music just like anybody else, but it’s a weird relationship when you’re a musician.

Would you consider your music specifically ‘Canadian’? Do you feel an affinity with any other artists along municipal, provincial, or national lines?

TH: On the local level, my friends who work in the art community, for sure. But beyond that, anything that’s specifically ‘Canadian’ about my music is totally garbage. My peer network is international. It’s people all over the place who I know, and respect their work. It’s not really delineated by traditional nationalist ideas. That’s a kind of dying notion in some ways. Like super locality, for sure. That influences in certain ways, but beyond that? Do I reflect something fundamentally Québécois? Don’t think so.

Huge congratulations on your Juno nomination, by the way. What’s your beef with [Nickelback’s] Chad Kroeger?

TH: It’s my one chance to possibly take him out. And I think for the sake of ‘Canadian’ music or whatever, it has to end. A lot of damage is being done.

Have you ever been abducted by aliens?

TH: Not that I know of, but I’ve had strange dream states that could have been the result of a visitation. I don’t know. Not sure. Have you?

Yeah, but this is about you.

TH: But this has to be part of it!

I’ve seen one. Four of us saw one in Telluride this summer.

TH: What!?

There was this thing that came up over the mountain ridge, it was brighter than any star in the sky, and the way that thing moved? Nothing is supposed to be able to move like that. It was serious. Colorado’s got some weird shit going down.

TH: Oh yeah? That’s pretty whack man!

So 2012: good times or end times?

TH: I’m generally an optimist and I tend to not buy these Eschatological narratives about our time. I don’t know. I wasn’t worried in 2000. Y2K? I wasn’t worried about Nostradamus’ certain end time. I’m not a peak oil person. I’m not a biohazard apocalyptic kind of freak. I don’t have a supply of weapons or gold bars under my house, but I don’t know.