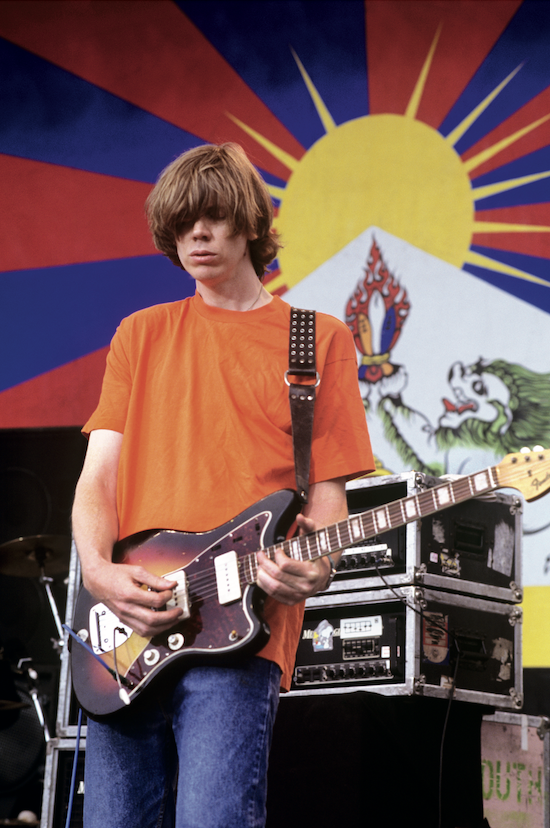

Thurston Moore at the Tibetan Freedom Concert, NYC, 1997, by Ebet Roberts

"I wanted to be the physical manifestation of a fanzine – that excited energy for whatever was happening in our community", says Thurston Moore, that energy still emanating via Zoom-link from the cradle of guitars, books and vinyl that is his west London flat.

The singer/guitarist is talking about the days before his band Sonic Youth shifted rock’s paradigm by adulterating its DNA with avant-garde technique and maverick intent. He’s referring specifically to the dawn of the 80s, when he spent every waking hour attending gigs, organising gigs, rehearsing for gigs and proselytising for New York’s early 80s post-punk scene. But the truth is that Moore has never relinquished this energy.

It was there in the mid-80s, when Sonic Youth first signed to UK imprint Blast! First and Moore hipped label-owner Paul Smith to the fecundity of underground rock in America, inspiring him to sign Big Black and Butthole Surfers to his label and helping to set a slow-moving noise revolution into motion. It was there when, as Sonic Youth took their first uncertain steps into the world of the Major Labels, Moore tipped his new management and corporate paymasters to a mercurial trio from the Pacific Northwest who would go on to become perhaps the most important rock band of the 90s. And it has endured in subsequent years as, slipping easily into the role of noise-rock elder without ever dimming his youthful fervour, Moore has testified on behalf of arcane Japanese noise rock, ear-lacerating free jazz and obliterating death metal with a zeal that is as edifying as it is inexhaustible.

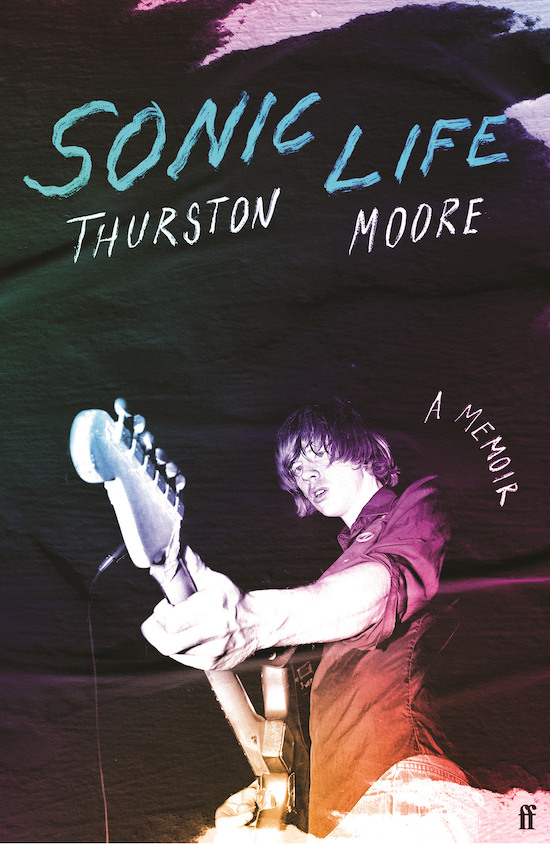

That energy radiates from each of the 472 pages of his new memoir, Sonic Life, which charts his journey from first contact with his older brother’s copy of The Kingsmen’s ‘Louie Louie’, through to delivery of Sonic Youth’s final album, 2009’s The Eternal. The original draft of Sonic Life was, he estimates, eight times as long as the finished edition. This would make it significantly longer than Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, and he doesn’t write off the possibility that unexpurgated text might see publication one day. But the several years he worked on the book were, he says, a process of refining Sonic Life’s purpose and focus.

"I needed to strike a balance between writing about events the readership would be interested in, and those that were personally significant for me", he says. "I wanted it to be the story of a personal adventure, an investigation of why music became my vocation, and why it was this subversive, marginalised music, as opposed to anything else. And I don’t think I ever really answered that question", he laughs, softly. "I don’t really get into too much self-analysis at all. I thought I would. But then I realised, I don’t want to."

Certainly, the lens of Sonic Life often pans sharply from Moore’s interior life to the electrifying panorama of noise that surrounds him. Patti Smith at CBGB, Public Image Ltd at the Ritz, the Minutemen at Folk City: Moore was there, and recounts what these epochal moments felt like from the audience, as a young man eager to connect with this wider world, to embrace this as something important, to make himself a channel of this noise. An early influence on Sonic Life was Michael Azerrad’s This Band Could Be Your Life. "It was one of the first tomes that dealt with this era, this secret history of underground rock", Moore says. "Of course, I read the Sonic Youth chapter first, and then the rest. But Michael was too young to have attended, say, the Minutemen gigs he wrote about. He loved this music and wanted to honour it. But there was something lacking from the text – the exuberance, that ineffable je ne sais quoi of energy in that room at that time, musicians doing something you really haven’t seen anybody do, the way it sounds, the emotions on stage, how they’re keying off each other… All of these different aspects were about being right there, at that moment. And he wasn’t able to write that, he could only write from the documents. I knew that when the time came to write about Sonic Youth, and what moved me to create our own music, I wanted to write about that feeling.”

Sonic Life’s focus on that “ineffable je ne sais quoi” means that, when the book does indulge in self-analysis, it is revelatory. One surprising vignette involves the teenaged Moore’s foray into anti-social behaviour. Working late at an all-night coffee shop in his hometown of Bethel, Connecticut brought him in contact with what he calls “real delinquents”, including an older boy from an abusive family whose fearlessness and hunger for trouble were intoxicating to Moore. The pair would tool around Fairfield County in Moore’s beaten-up VW Beetle, drunkenly instigating car chases with other teens and hurling empty beer bottles at passersby. Their hijinks escalated, until they foolishly burgled Moore’s neighbour’s home, stealing their copy of Joni Mitchell’s Court And Spark, and lit off to Michigan, to hide out with his tearaway pal’s relatives. But Moore’s car broke down in Ohio, and the Michigan relatives wanted nothing to do with him. He was picked up by police while hitch-hiking back to Bethel, appearing in court “in handcuffs and leg manacles” for breaking and entering.

"I was acting out", Moore says now, of an episode painted in Sonic Life as the moment that scared him straight, that sent him towards New York City and his destiny. "I was in my late teens and my father had just died – the rudder was gone. I lived in mid-70s rural America, and there were some bad news bears out there. That trouble, that energy, was appealing."

Was his fascination with punk rock, which preceded his walk on the wild side and which endures today, a similar hankering for a dark energy he found appealing? "Punk rock presented itself as a delinquent music, but that was high theatre, in a way", he says. "The Ramones, in their leather jackets and ripped jeans, looked like street thugs, but they were just working class kids, oddballs who nobody else would hang out with. And that was really relative to a lot of our experiences. I felt like an odd duck in my society of teenage life."

Moore says his lifestyle was "defined by my father, who was an intellectual". George Moore was a professor who taught art appreciation, philosophy, humanities and phenomenology at nearby Western Connecticut State College. "We had books in our house, we had music in our house, we had art in our house. And visiting other houses of people my age, there were no books, there was no music, there was no art – just knickknacks and bric-a-brac. I realised we were different. But I didn’t want to exchange what we had for what most of the rest of America had, which was just sitting in front of the television set. I always felt at odds with the expectations of standard society, and was really drawn to finding some representation of ‘otherness’. I recognised it immediately in the first image I saw of Iggy Pop, spray-painted silver, standing on the audience’s hands. Then it was an androgynous Patti Smith standing in ripped leather pants on a subway platform in New York City. It was all a far cry from James Taylor in a rowboat with a dog, dressed in hippie finery. I recognised something in the urban music of New York Dolls, or Patti Smith, or the Ramones, that just sounded far more erotic than the country hippie thing. There was a thrill there that I wanted more of.”

"An American family, Bethel, Connecticut, 1971. Left to right: my father, George; mother, Eleanor; brother, Gene; sister, Sue and me at thirteen", Thurston Moore

The hunger for this thrill drives and defines the rest of the book, and indeed Moore’s adult life. In Sonic Life he characterises "the only future I cared to dream" as "a devotional life in service to rock’n’roll", and describes his new home of New York city as "where I could write songs, play guitar in a band like no other, write books of poetry, spend my days and nights in deep-soul streets of inspired energy – the place where I could be protected by rock’n’roll". His childhood friend, Harold Paris, who accompanied him on his first forays to CBGB, slowly fades from view, at first alienated by Moore’s new dirtbag NYC punk cronies, and later finds a partner and a life consumed by things other than losing brain-cells in dingy clubs every night.

Moore’s unebbing commitment to punk-rock later prompts Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon – and Moore’s wife from 1984 to 2013 – to make wry comment about “teenaged men”, and how the rock & roll environment offers men a space to evade the responsibilities and perhaps disturbing changes wrought by physical maturity. Moore mostly draws a veil over the intimate details of his relationship with Gordon in the text of Sonic Life, beyond chronicling their early courtship and detailing the later complexities of blending family life with the (un)reality of the rock & roll existence. "I don’t want my 28-year-old daughter to have to read what her father has to say about his family, his relationship with her mother – the book is not the place for that", he explains. That he shares this "teenaged men" crack in Sonic Life suggests he saw a kernel of truth in Gordon’s observation.

“There was definitely a feeling I had, that I should probably have the responsibility of growing up and being an adult", he admits. "A lot of being in a band dealt with a certain youthful exuberance, and I felt at odds with that – a musician gets into their later years and they’re still acting as if they were 20. I didn’t really want to make it too much of a gender thing, but rock & roll has always been this white male imperialist character in the culture. So it’s funny and valid to call out teenaged men, or what Kathleen Hanna called "rockstar toddler-ism", which I thought was great. I didn’t really get into the gender aspect much [in the book], and I could have talked more about this feeling of being a junior partner in a relationship."

That responsibility of being an adult partly motivated Sonic Youth’s transition from independent labels like Blast! First, SST and Homestead to David Geffen’s DGC Records with 1990’s Goo. “When Mark Kates, who was working in radio promotion at DGC, came up to us after our show at the Pyramid Club and asked us if we’d talk to his label, we were at the age where we thought, ‘Why shouldn’t we entertain this notion now?’,” Moore remembers. That slow trickle of bands from their scene entering the world of major labels began in the mid-80s, with Hüsker Dü and The Replacements as pioneers. “It was very radical at the time,” says Moore. “Like, how could Hüsker Dü be on Warner Bros? That doesn’t make sense! And the albums they put out were no different than any of their others – in fact, they were possibly less exciting, because without the connection to the independent labels, they were kind of defanged.”

When the offer finally arrived for Sonic Youth, they quickly accepted. “Our relationships with SST and Paul Smith were slightly funky – they didn’t have it together when it came to accounting. With SST, you understood that whatever monies were made from your record sales went into making the next album by Saccharine Trust or whoever. That communitarian ideal was a socialist thing we loved, but it was always suspect, especially in the late 80s, when bands like ours started doing bigger business.”

The group took the meeting, albeit “in a spirit of giddiness. We met [legendary music industry mogul] David Geffen and he gave it this hard sell, how his was the only label we should be on. I realised he didn’t know who we were. He kept talking about John Lennon having been on Geffen, and I said something really snarky like, ‘I really liked that Cats record’. And he’s like, ‘Excuse me?’ Because Geffen had released the soundtrack to the Broadway smash Cats, and I thought I was being funny, but he didn’t get that. I said, ‘SST doesn’t have Cats, SST has the Minutemen and Saccharine Trust. Let’s be real here, that’s what’s buttering the bread here – the fucking Cats soundtrack.’”

Nevertheless, Sonic Youth signed with Geffen, who bankrolled a series of increasingly avant-garde records over the next two decades. “We went into it with an idea of how absurd it was, to be a band like us on a label like this,” Moore says. “I was always very attuned to absurdity in music. Like Japanese noise music: ‘Every single cassette sounds the same, and it sounds like a washing machine? I’ll take them all, please!’ But also, there was health insurance, and in the USA we don’t have a socialised health system. And it allowed us to have a little influx of money, so we could live off something other than peanut butter and onions. There was a lot of outcry from the community – people were telling us, ‘Major labels are notorious about ripping-off musicians … those dinners they’re taking you out to, you’re actually paying for them…’ ‘All these contracts are old bluesmen contracts …’ But we weren’t stupid. That was the kind of argument we certainly would have with somebody like Steve Albini. The first album we did for Geffen, Goo, we purposefully got Raymond Pettibon [underground illustrator who defined Black Flag’s uncompromising visual style] to do the cover, to ‘keep it real’. But as a juxtaposition, we did this high colour Michael Levine photo shoot inside the record, with us dressing up like pathetic peacock rockers. It was about us having fun with that dialogue.”

The Major Labels were the big bad ogres of 90s culture, supposedly appropriating artists and abusing their work and fleecing them, though they seem like benevolent renaissance-era patrons compared to the big streaming companies, who’ve liberated musicians from the dream of making a living from their art. Moore himself doesn’t stream, saying “I don’t get as much out of the listening experience – it doesn’t have the same friction as playing a cassette or a record. And that’s just me being an old man, but I don’t get any spiritual connection.” At 65, he says he doesn’t listen to music much anymore anyway. “I feel like I’ve decoded a lot of what I really enjoy. I’m more interested other aspects of it, in signifiers. I’m more interested in what the record looks like and feels like and smells like, because I know what it’s going to sound like. I very rarely play records, but I like to have them. They’re objects that that I glean a lot of creative impulse and energy from, just knowing that this activity is going on.”

Sonic Youth backstage in New Jersey, 1987, by Chris Petersen

Sonic Youth released another album this summer, a live recording of one of their final shows, lovingly pressed by Silver Current, the label run by Howlin’ Rain’s Ethan Miller. The band themselves have been dormant for twelve years now, ceasing work after Moore and Gordon’s marriage broke down and Moore moved to England with his now-wife, Eva Prinz. I ask Moore if he misses Sonic Youth as a vehicle, if he feels there was anything else they could have achieved. “There could have been,” he reasons, “but I also feel like we did more than our share, more than enough of being a band. We were purposefully democratic, a true forum for this music to exist. But things changed as the band got older and people moved outside of New York and became more domesticated. Kim and I had Coco, and moved two hours north of the city; Lee has two children."

“The world around us was changing,” Moore continues. “In some sense, Sonic Youth could have continued forever, but I was really interested in going solo. Because I wanted to call the shots – I didn’t want to have to run things by three other people all the time. The band no longer existing was certainly defined by Kim and I getting divorced – like, ‘We broke up, has the band broken up as well?’ That certainly became the narrative, though there was never anything official announced. In that sense, it’s like we never broke up – we just don’t play anymore. And I kind of like that. By calling the final album The Eternal, it allowed for it to be this ‘POOF!’ into the magic universe of foreverness. That title was drawn from my interest in this idea of expressing obliteration through the music of black metal, which I was listening to a lot at the time. But it also tapped into this slightly mysterious, religious undertone of the eternal in religious literature, be it Judaism, or Catholicism, or Buddhism. When we titled it that, there was no notion of ‘this will be the final Sonic Youth record’. But in retrospect, of course it was. A lot of my lyricism on that record was all about going into a new relationship.

“Could we have continued? Sure. But I’m glad we didn’t. [laughs] Only because it allowed me to have the life that I have now, that I can’t imagine not having: living here in London, with Eva, working together all the time. Sonic Youth could get back together again and do huge business, for a second. But it would be a nostalgia act, and I’m not interested in that. I do not want to be part of that, being on these nostalgia bills. Even when I see Blondie and the Pretenders and all these bands on those bills… I love those bands. But I don’t want to be part of that, I don’t want to exist like that. I especially don’t want Sonic Youth to exist like that. So I’d rather just let it be The Eternal. Otherwise it would be a little too much about making money. I find that sort of unsightly.”

The Eternal is where Sonic Life concludes. “I was gonna continue and write about my life post-Sonic Youth, post-divorce, going into my new London lifestyle and having a whole new world,” Moore says. “But I didn’t want to write about that, at least not yet. It was Eva’s idea, to end it with the words ‘the eternal’. I remember her saying, ‘the last record is called The Eternal, why not just write those words?’” Moore has continued to make music under his own name, but is enjoying the shifts his life and identity have taken since Sonic Youth ceased operating. “At this point, I’m more interested in being more still, and not being on the road so much,” he smiles.

While he’s no longer so plugged-in to the weirdo noise frequency that was his obsession for decades, Moore remains that fanzine-made-flesh – he’s just tuned his energy in to the printed word now, rather than sound. “I want to continue writing. At some point I want to write something that extends past the last pages of this book, but I also want to write novellas, novels, stories. One thing that led me to writing Sonic Life was just wanting to write. Most music memoirs are written in conjunction with other writers. But I really wanted to establish myself as a writer – the only other person who worked on this book was my editor, telling me to get rid of pages. There was no linguistic exchange with any other writer. I want to get more into writing, per se. One of the most enjoyable things I’ve ever done was just hammering away at this book.

“I just saw Colson Whitehead read at the South Bank,” Moore adds, “and he said, ‘When I’m writing, one of my prerogatives is to be a better writer than I was last time, to continually learn from what I’ve done’. That’s how I always felt about writing songs – each record I thought, ‘the next record is going to be better’. I was intrinsically learning my own style of craft. I’ve always felt some apprenticeship about all of this. I’ve never had a sense of resting on laurels, or been concerned over feeling comfortable.”

Sonic Life is published on 26 October by Faber. Thurston Moore is in conversation with Stewart Lee at the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room on 29 November