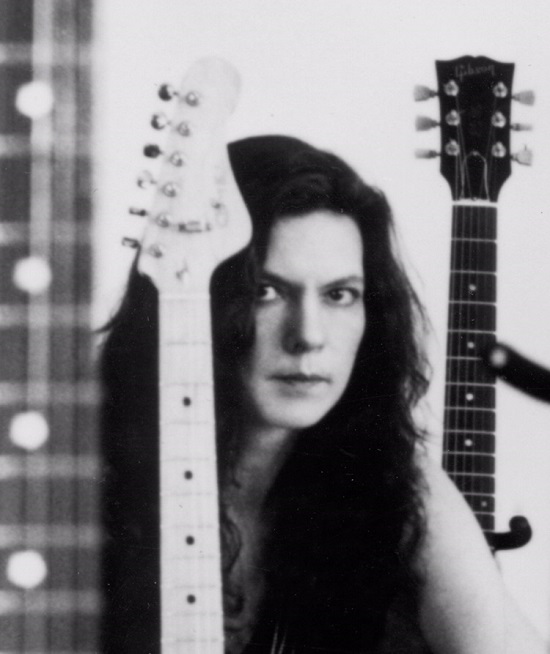

Thurston Moore portrait by Vera Marmelo

Thurston Moore returns to the Barbican on April 14 with his ambitious Galaxies: 12×12 project. The former Sonic Youth vocalist/guitarist is a composer, conductor and member of an orchestra of 12 string guitar players.

Moore has been interested in the sonic possibilities offered by the 12 string guitar since the 1990s and played a solo set on the instrument at the Barbican in 2016 while supporting Michael Gira.

The dynamic dozen is constructed from three current Thurston Moore Group members including Deb Googe and James Sedwards, renowned improvisor, theorist and writer David Toop, Jonah Falco of Fucked Up, Rachel Aggs of Sacred Paws, Susan Stenger of Band Of Susans, Jen Chocinov of Schande, Alex Ward of N.E.W., Eugene Coyne and James McCartney.

The performance is split into two halves, the first acoustic and the second electric, and was inspired by a Sun Ra poem. The show will also feature films by London writer Radio Radieux.

We caught up with Thurston just prior to rehearsals to talk about the writing of Sun Ra, 12 string dynamics and NYC guitar orchestras of the early 80s.

The Barbican describes 12 x 12 as "not a rock & roll band but an orchestra" with you as conductor and composer. Your milieu these days seems to be the world of improvisation (even the Thurston Moore Group, I believe, while playing songs in the more traditional sense tends to also have more free form, improvised or semi-improvised noise sections). What has it been like engaging in such an ambitious but (presumably) 100% scored venture?

Thurston Moore: My interest in free improvisation, as a music genre, is the idea, shared by many of its practitioners, of the music, while freely improvised, being a composition in real time or, as Allen Ginsberg would note in regards to Improvised Poetics, "composing on the tongue". I find that free-improvisation inspires and informs my predilection to songwriting and, even before I had any defined realisation of free-improvisation as a discipline, I was interested in open forms co-existing within composition. It certainly was the case in Sonic Youth early on and has continued to this day as a relationship I feel most intrigued by. In retrospect I see Sonic Youth informed by the outsider aesthetics of No Wave music which, in itself, was wholly fascinated by Free Jazz and (sometimes pseudo-) academic considerations of Chance Musics. And also completely reckless punk rock FUN.

In this ensemble we will be working from notated scores, the acoustic section a series of guitar staves and the electric section more from instructional cues. There are a few times in the pieces that will allow players a bit of personalized free expression. But unlike total free-improvisation I have my eye on them as ringleader.

In practical terms, you can’t be waving out time signatures with a baton if you’re playing. How does this work in practical terms, with things like timing and changes in intensity or volume (in terms of you being the conductor)?

TM: I’ll set the time signature, which I prefer to be human and vibratory as opposed to click-track strict. We will discuss the dynamics in rehearsals, which are coming up very soon. I have yet to hear anything beyond my own guitar un-amplified in my flat.

Once you get more than several musicians together all playing the same instruments together you run the risk of the overall sound simply becoming louder and less distinct. What are the various strategies you use to keep the overall sound dynamic with as much separation between players as you require?

TM: I was asked by the Barbican if the venue needs to be prepared for twelve 12-string guitars blowing the roof off the place. I think there is always the expectation that I will bring the noise, as it were. While I’ve always been more than willing to employ noise in music, it has never been about being loud, louder, loudest. I find a lot of times when I am in concert with free improvisers the other players feel it is time to crank shit up, while I’m feeling it’s time to crank shit down. But I understand the tendency, for players and listeners, because of my history in experimental rock music, to perceive me as a ticket to noise.

Deb Googe

Given your practice over the years it would be remiss of me not to ask if any of the players were using non-standard tunings or prepared instruments? It must be twice the pain to retune a 12 string right?!

TM: There are two tunings being used, one dedicated to acoustic, the other electric. The acoustic, from sixth string to first, is C-G-D-G-C-D. Which is the tuning I’ve been writing in, primarily, with my London based group the last few years. The electric is D#-A#-D-F-A#-C, a tuning I have used in the past, but rarely. It is a bit more work tuning and re-tuning a 12-string, certainly, but it is always twice the rock & roll reward.

Can you tell me a bit more about why you actually like the 12 string in this and other instances above, say, a nylon strung acoustic or an electric guitar?

TM: I like playing any guitar I suppose. I originally wanted to be a drummer when I was a kid, but didn’t have the foot/hand/brain coordination. I come from a music family, the piano being the centre of play, which I gleaned from my father and granny, both advanced technique players. But I liked the noise of electric guitar and the sensuality of the vibrating speaker cone of the amplifier, it really did, and does, express the blood and passion of glorious youth and beyond. The acoustic guitar, specifically the 12-string, can evoke a wholly other sonic presence, and as soon as I got into playing it, in the tunings I was always experimenting with, I grew to become very intimate with it. I would say the acoustic and electric have equal value for me as per means of expression.

Can you tell me about the Sun Ra poem that acted as partial inspiration for this project and also can you tell me about when you saw him playing live outdoors in New York City?

TM: Sun Ra’s writing, particularly his poetry, has always struck me as almost Zen, in nature. It rings of ‘Beginner’s Mind’ and is both lyrical, spiritual and, at times, meta-political. At the early stages of composition I was seeking a text to express what I felt was the ineffable in expression with purely instrumental music. I looked at work from various poets I admire (Alice Notley, Bernadette Mayer, Anna Mendelssohn, Anne Waldman) and remembered this poem by Sun Ra and upon revisiting it I knew it was the jewel. I had seen Sun Ra perform a number of times in New York City since moving there in the 1970s. One gig was him lecturing which began with him speaking from outside the small club and entering the room speaking, continuing on stage speaking, then exiting the room still speaking! Sun Ra and his Arkestra performed what some consider their final gig with him with Sonic Youth in Central Park, New York City at the outdoor amphitheater there. Sun was somewhat wheelchair bound and sat in our dressing room with a slight beatific smile and an orange dyed beard. It was grey day threatening rain. The Arkestra played first and, yes, the clouds parted and the sunshine broke through. It was amazing as the weather report had a different idea. I was fortunate to have a few conversations with the man, one of which concluded with him whisper-singing in my ear, “Play the cosmos’ song." So this poem I feel is appropriate.

What’s the name of the Sun Ra poem and where was it published? And is there anywhere where people can read his poetry today?

TM: The Sun Ra poem is ‘The Satellites Are Spinning’, which is essentially the lyrics to a song of his, which different versions can be found online in the usual places, or by entering a physical record store space and locating the LP, CD or cassette that it exists on. Sun Ra’s poetry was issued privately by him throughout his life and is, as you’d suspect, quite rarified. There is a great compendium of it all collected by James L. Wolf and Hartmut Geerken in the tome Sun Ra: The Immeasurable Equation – The Collected Poetry And Prose published by a small press called WAITAWHILE. Sun Ra’s poetry, lyrics, and prose is very interesting to me in the context of African American literature’s relationship within its own commonality. A book I’ve been meaning to read which examines this sentient world, which is still outside of academia, and possibly the better for it, is Epistrophies: Jazz And The Literary Imagination by Brent Hayes Edwards.

Can you tell me about the galactic theme of the concert and the division of the programme into Earth and Sky sections?

TM: It was wholly informed by what I gleaned from reading the Sun Ra poem. But it fits into readings and contemplations of what defines the essence of our existence together on this planet. Without being escapist I wanted it to be more in tune to the realities and mysteries of the sound & vision universe(s) we cohabit.

Susan Stenger

Purely based on assumptions I’m making, when I think about this I’m mentally hearing something with quite a NYC minimalist/No Wave/Glenn Branca/Rhys Chatham sort of vibe but what does it actually sound like stylistically – can you talk me through it?

TM: I understand how me composing and conducting a mass guitar piece can only smack of Branca/ Chatham reference. As I was intrinsically intimate with that scene I feel the exploration of the ideas of multiple, alternate tuned guitars is as much mine as those gentlemen, both of whom I hold in high regard as artists and friends.

Obviously your association with Glenn Branca goes way back. Lee Ranaldo is one of the guitarists on The Ascension from 1982 and you and Lee play on ‘Music For The Dance Bad Smells Choreographed By Twyla Tharp’ from the John Giorno split (1982) and ‘Symphony No. 3 (Gloria)’ from 1983, which features Michael Gira amongst many other guitar players. And that’s not to mention Neutral Records putting out Sonic Youth’s first LP in 1982. Was your first experience of being in a large ensemble via Glenn Branca?

TM: I had first seen Glenn play with his first two New York City bands from 1977-78, Theoretical Girls and later The Static. Both were extremely aggressive in their attempts to break down any traditional aspect of what an amplified electric guitar in a rock band format could be. It was thrilling to hear and witness, in all it’s primal yet artful invention, and I realised immediately it was part of a lexicon I was piecing together for what would become Sonic Youth. Those two bands I felt were of equal value to the other No Wave groups I was seeing (Mars, Contortions, DNA) but it wasn’t until I chanced upon hearing Glenn perform a six guitar (with drummer) instrumental concert, at Arleen Schloss’ A-Space on Broome St in NYC, that I heard something I had been ruminating in my head. A roaring supersonic guitar action music that ripped through heaven. I immediately answered an ad in a local newspaper for guitarists that Glenn had placed and we connected. At the same time I began to hear Rhys Chatham perform and he had a more benign presence, both personally and in the core of his music. Both Rhys and Glenn utilised musicians from the same community in those days. Which included Lee Ranaldo and myself.

What do you feel you learned from him about how large groups of guitar players work together live?

TM: From Glenn I learned that focus and dedication can result in a stunning new sound world. Glenn came out of a radical theatre group (Bastard Theater) from Boston, Massachusetts and presented himself in a somewhat wild, performative manner, some kind speed freak contrarian maestro. It was very exciting and unlike anyone else’s work. I didn’t much care for the authority historically inherent in band leaders, be it Glenn Branca or Buddy Rich and I decided early on to offer polite diplomacy, mutual respect and non-hierarchical dialogue in such situations.

I believe he had quite a vigorous conducting style!?

TM: He’d get into it, that’s for sure.

I’ve seen you play 12 string before, once onstage at the Barbican supporting Michael Gira (and I feel possibly like you were playing one at the Union Chapel when Michael Chapman was in support but I could just be dreaming this). Where does your interest in this instrument come from and can you sketch out your history with playing it?

TM: I purchased a 12-string sometime in the 1990s as I was interested in investigating acoustic guitar music beyond the six-string, which I had dallied around with a bit. I had been finding myself falling into the magic of acoustic players like Joni Mitchell, John Fahey, Davy Graham, and Sandy Bull. The realisation of their experimentation was something I never looked at too much previously being so immersed in the electric guitar music so profuse in punk (Andy Gill, Tom Verlaine, Viv Albertine), jazz (Sonny Sharrock, Takayanagi Masayuki) and the entire radical guitar scene Sonic Youth was concurrent with (MBV, Swans). I was indeed playing 12-string at that Union Chapel gig. I was touring with my Demolished Thoughts project I had recorded at Beck’s studio (Samara Lubelski – violin, Mary Lattimore – harp, Keith Wood – six string acoustic, John Moloney – percussion). Soon thereafter I toured the UK with Michael Chapman trundled in his car, a fantastic trip discovering corners of England I never before experienced.

David Toop

You’ve assembled quite a formidable orchestra. As well as two members of your current group, you have the renowned theorist, writer and improviser David Toop. When did you first work with David?

TM: I was always aware of David Toop in the context of his writing and his playing on critical LPs of the 1970s/80 era of British free improvisation. And, of course, his appearance on the mythical Obscure label of Brian Eno’s in 1974. We met when my partner Eva and I were preparing to publish a bound facsimile of MUSICS, the communitarian fanzine edited and published by Toop, Steve Beresford, Maggie Nichols, Evan Parker and just about every other active participant in Britain’s free improvisation scene of the sharing of ideas about the rarely discussed and marginalised music making spanning the planet. I had already had a history playing at times with Steve Beresford and as he and Toop were re-forming their group Alterations with Peter Cusak and Terry Day, they asked me to guest one evening at Café Oto. A remarkable honour. We’ve subsequently played together in varying contexts and it’s always been surprising and thoughtful.

How far back does your association with Susan Stenger from Band Of Susans go?

TM: I knew Susan from both her work in the Band Of Susans group in 1980s/90s New York City and her playing in Rhys Chatham’s ensembles from time to time. Back then our paths were sure to cross due to like-minded interests and mutual connections. While primarily regarded as a highly regarded sound artist and composer she has an amazing history working with such remarkable people as Phil Niblock, Michael Clark, Iain Sinclair, and Alan Moore.

Have you collaborated with Rachel Aggs and Jonah Falco before?

TM: I’ve done gigs with Rachel with her band Trash Kit, but we’ve never jammed together. Jonah I met a few times when he was with Fucked Up as a drummer. I had put together a somewhat all-star band [Demolished Thoughts] for South By Southwest years back (J Mascis, Don Fleming, Allison Bush of Awesome Color and Andrew WK). Andrew WK got lost in action and we needed a bass player literally ten minutes before we were to hit the stage. Our repertoire was all early 80s first generation US hardcore tunes by Minor Threat, SOA, Gang Green et al. Jonah was hanging out and we strapped the bass on him and he picked up and raged through all the tunes. It was unbelievable! I haven’t seen him since but I had heard he was banging around London so I immediately reached out to him to participate.

Is this a first time collaboration with any of the musicians – please tell me about them.

TM: It is indeed the first time I will be playing with a few. Of course I’ve spent many enchanted hours with the awesome Deb Googe and the remarkable James Sedwards. And I have played music off and on through the years (since he was a teenager) with Alex Ward. Joseph Coward is a local songwriter who I’ve always been impressed by. I played a little bit of noise on one of his LPs. He has a new band called Camp X-Ray that are supposed to be quite wild and interesting. James McCartney I met years back at the All Tomorrows Parties event that Sonic Youth curated. We’ve stayed in touch and after I moved to London we’d get together and have long talks about music, art, life. He’s a fabulous acoustic guitarist and I look forward to finally collaborating with him. Both Jen Chochinov and Eugene Coyne I have not met as of yet but they were highly recommended by other players in the ensemble and I can’t wait for the sonic lift-off!

With thanks to project director Abby Banks and Ecstatic Peace