In May 2014, I was completing a master’s course in journalism and I had to write an essay on media ethics. The previous month Peaches Geldof had died, and I decided to look at the coverage in all of its over-sensationalised, weird, grotesque glory. I read a lot about Thomas Cohen, her widower, who had previously been in a band called S.C.U.M that I’d heard on the radio a few times.

The reason I point this out is because every interview starts with some acknowledgement that you’ve done your research and you know an amount of information about the person opposite you. It’s always odd. But in this case, as will be the same for many of you reading this, there’s an edge of uncomfortableness because your knowledge of events is compounded with a sense that said knowledge has been filtered through a shifting, unreal landscape of press misdirection. And for me, I hadn’t just assimilated this pseudo-knowledge via living in the UK during spring 2014, I’d dissected events and the way they were presented to the public, and got a good grade because of it.

So I felt nervous, but prepared, for this interview. I’d be informed, understanding and ready to ask fascinating questions about a person who’s had an interesting life, like the good, nodding, indie mag journalist I am. I’d listened to the album and loved the instrumentation and production, and I’d enjoyed the myriad references to ’70s American rock and was impressed that Cohen hadn’t sought to pretend this album was dealing with anything other than a hugely painful period in his life, by bringing simple metaphors to the fore.

But I wasn’t prepared. Because Cohen is 25 and, when he arrives, is speaking to his PR about childcare. I’m 24. I feel like the waiter in this branch of Patisserie Valerie has just given me a swift punch to the abdomen. The courage Cohen has to sit in front of me when he knows that, not only am I definitely going to ask about the songs he wrote when Peaches died (the whole album isn’t about her, but it’s ordered chronologically and it’s easy to map a grieving process), he knows that the MailOnline might use some of the quotes. It’s easy to reckon that because you have an inkling of how the tabloids work to manipulate you, that you’re able to humanise their subjects in spite of their techniques. But you’re not. Cohen was a cartoon character to me until he ordered a pain au chocolat.

I may have done well in that essay, but I didn’t get onto the Daily Mail‘s trainee scheme when I graduated (something I convinced myself would be ‘good experience’). That’s because I’m not the kind able to push for the scoop, or do anything a tabloid journalist would have done, when confronted by Cohen. He is charming, honest and open with me. He’s peaceful, funny and self-aware. And I can’t even bring myself to say the word ‘Peaches’ during the interview. Because even though releasing Bloom Forever is an action that invites press attention, no one deserves to be pried open and peeked at, whether the person looking reads the sidebar of shame or tQ. So I’m not sorry I didn’t ask Cohen about drugs, scientology or Daisy Lowe. I asked about his album and the implications of making it, and he answered beautifully.

At the end of January you played your first show as a solo act and first since S.C.U.M broke up in 2013. How did it feel to be on stage without the band?

TC: I felt much more present. I used to find shows quite difficult. It was a weird band. It was always quite an odd feeling when we were performing. As much as we were close, and we still are close, it was always a very strange atmosphere.

When you were in S.C.U.M did you think about striking out on your own?

TC: I loved being in S.C.U.M. But I think I was working on stuff before we properly disbanded. Our last show was at Punkt in Norway, which Brian Eno put on. Eno did a conference beforehand and he was talking about how he had to look for new music for the festival and the first thing he did was put on 6 Music. He said he heard this song that sounded like "nothing else he’d ever heard before" – it was a S.C.U.M song called ‘Amber Hands’. Which was beautiful and hilarious, because we literally lifted the riff for ‘Amber Hands’ from ‘Needle In The Camel’s Eye’.

Is that the most weirdly arrogant thing he’s ever said?

TC: A very humble man who’s subconsciously arrogant. It’s quite human to be like that, isn’t it? Like how I enjoy it when my children say words like I do.

What do your kids think of you being a musician? Are they old enough to get it?

TC: I don’t think they’re old enough. They are two and three.

‘Bloom’ and ‘forever’ are the two middle names of your youngest son. In the context of the name of both the album and your child, is ‘bloom’ a noun or a verb?

TC: I think it’s probably a verb.

I felt like it was an instruction: "Bloom forever!"

TC: When I thought about it in that context I found it so overwhelming, as it wasn’t me that came up with the name [it was Peaches]. It totally stopped me, that thought. It’s kind of beautiful.

You hadn’t considered it in that way at the time?

TC: No. But I think it was meant to be that way. When I realised, I couldn’t really call the album anything else.

I’d like to ask you about why you chose to order it chronologically. Was that a decision you made at the beginning, or was it a decision you made in light of what happened?

TC: It kind of did it itself. I hope it’s not laziness. It just seemed that… well, it seemed to make sense for a record where every song is personal. It’s a story.

Did you worry that doing that would open it up more?

TC: When I was making the record I was unsigned, in Reykjavík and I didn’t have a band, so to speak. So I wasn’t really thinking about outside opinion. Which is great. I guess it’s only now that I’ve come out of that bubble that I’m like, "Oh god", this is actually the place which I unfortunately exist in, where you’re open to every sort of scrutiny possible. But when I was making the record I didn’t care about that. And I don’t think it’s disassociation, I think it’s actually the truth of my outlook.

How does it feel to be in the headlights now?

TC: Well, this feel nice! But sometimes it doesn’t. I think it’s a weird concept anyway. And I think everyone takes the natural position of being on the defensive the whole time, which therefore actually makes for a kind of strange conversation with someone you’ve just met.

Tell me about Reykjavík.

TC: It was surreal. Really intensely beautiful. Iceland literally looks like the moon. And when we arrived in Reykjavík it was much smaller than I was expecting. The studio was in the fishing harbour and I didn’t really leave that much.

At what point in the album’s chronology did you start writing from Iceland?

TC: ‘Country Home’.

That’s a pretty heavy song to go into the second you get there.

TC: Well it was August, a couple of months after [April]. I had the riff. I wanted it to be this hippy dippy love song and I think I succeeded. But yeah, you know… when I got to Reykjavík I spent the majority of my time working on that song. I’ve never really felt comfortable enough to talk about writing it – it was quite a painful, manic and quite claustrophobic process. But that’s what my life was.

In that period between April and August had you been feeling out the song? Or did it come quickly?

TC: I wrote a lot in that period. And I started another song which I didn’t quite get done. I’ve still got it and I’d like to work on it a bit more. I wrote the beginnings of that song about four days after it had happened. Then ‘Country Home’, dealt with everything that I was feeling later. I also made a decision at that point that I didn’t want to make a whole album about it. I don’t want to write Berlin, even though I love that record. But with ‘Country Home’, as soon as it existed and it was finished, it just became a song, you know? You kind of lose the emotion of a song when it’s finished.

But how did it feel to play it live?

TC: Way more intense than I expected it to. It’s much heavier live.

It is very sad, unsurprisingly.

TC: But, especially with that song, I was listening to David Crosby’s solo record quite a lot. Thank god I was and I wasn’t listening to, like, Neubauten. I think that makes it bearable and not uncomfortable.

How does it feel to put it out there, as a piece of music that goes beyond itself and transcends time and events?

TC: I keep thinking about that. I think there’s definitely some songs where I think, "Wow, that song’s come from the darkest, most painful place I could ever imagine". But you don’t know the story. Whereas certainly in England, I guess, with this record, if someone chooses to buy it and listen to it they kind of have the story laid out for them already. I think even when songs are just a metaphor about whatever, they are still equally as painful for the person who wrote them if they’re coming from that place.

On the whole you’re quite clear about the narrative in the album – there’s darkness to daybreak and so on. Were you just attracted to simple storytelling? Were you not tempted to obscure the events with lyricism?

TC: No. I wasn’t tempted to obscure it, just because of the music I was listening to. When something really extreme happens to you, you go and listen to a record and it affects you in a different way. Everything I was listening to would feel super personal. People would come to me and say: "Listen to this record, it’s super personal, you’ll really like it right now."

Can you talk me through a few of the artists you were listening to and how they impacted you?

TC: I discovered Townes Van Zandt when I started writing the record. I’m sure you can’t hear a direct reference to it because, you know, I’m from Eltham. But that’s what I was listening to. Every record, every reinterpretation of his songs. And I was listening to Tim Buckley and Van Morrison a lot, which definitely affected the way I recorded a lot of it. Judee Sill as well.

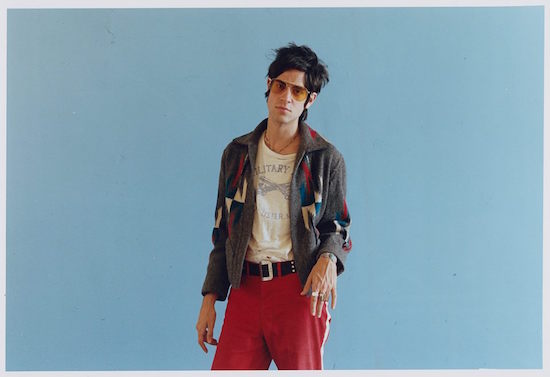

How about the cover? I asked my Facebook friends if it was a particular reference to anything and they came back with all sorts: Lou Reed, Richard Hell, Iggy Pop, Gram Parsons, Jim Sullivan, Melody Nelson, Mick Jagger…

TC: All of those, yes!

Is your aesthetic a composite, then?

TC: Well, it’s interesting because actually I feel like when I was writing the record I was much more influenced by female songwriters and the intimacy they allow you to have. As much as I love Tim Buckley, I don’t want to always hear about how good he is at having sex. And so the actual direct reference to the record cover is an Emmylou Harris record called Evangeline from 1981.

You look quite awkward and uncomfortable on the cover and in the video.

TC: I’m quite uncomfortable. I don’t know why, but anything I tried on this record that was dishonest was just binned. I was worried I was trying to veil the honesty of the record with humour, but then I realised that I’m not, and actually, musically, the record is kind of silly – it’s got minute-long guitar solos with key changes in them. When something tragic happens, suddenly you become hilarious. And I couldn’t not bring that into the music and the artwork. Again, I’m sure it’s a coping mechanism, but whatever. Who cares?

We all need them. At least it’s one that keeps everyone smiling.

TC: Yeah! It’s better to grow a sense of humour than to become an alcoholic.

Are you scared about having to talk about this over the next little while, even with a sense of humour?

TC: Sometimes. I don’t want to talk to a lot of people. I just don’t want to facilitate somebody else’s idea of some tragic human being. If I were to speak to certain people I would have to just be dishonest a lot of the time. I don’t think I’m scared though. I get it. The whole concept of gossip and celebrity is so archaic and it’s also so human and I can understand why somebody feels it’s important.

People who read magazines and tabloids and know your name in the capacity of your marriage and not much else – how do you feel about them hearing your album?

TC: It’s funny. Somebody in my band said to me, "I’m in your band because I like your music and I think it’s going to be interesting to see what happens." But I had to tell him that it doesn’t give you anything. No one cares about somebody on an independent record label! No one cares about your Townes Van Zandt reference. It’s like a hateful, un-nourishing sub-universe that exists but actually it doesn’t, not really. And it’s never going to have any sort of output: no one is going to read a newspaper and go listen to the record! That’s not how it works.

Although there are moments of very accessible, soulful pop. I wondered if you’d thought about writing pop songs for someone else.

TC: I don’t know if I’m that kind of writer. I’d never be asked! It’s like the backing vocalist for Snow Patrol that ends up writing pop songs, you know?

Are you proud of the album?

TC: I guess I’m proud of it. I don’t really sit back and think on what I did, but I certainly have never gone back and listened to the record and at any point got frustrated. I was very obsessive, and because I was that obsessive, when I was finished I was kind of relieved.

I forgot to ask earlier, is ‘Bloom Forever’ inspired by On The Beach?

TC: Yes. I don’t know how to play that song, but it was definitely something I was listening to a lot and really love. It’s kind of a different emotion, that Neil Young record, to a lot of other Neil Young records, and I feel like it’s probably one of his most complete records too. And I actually went to New York this summer and me and a friend hired a car and it was the only album we bought.

I guess better than asking if you’re proud of your record is asking whether it’s ‘complete’, then.

TC: I think so, yeah. I definitely feel like by the time I get to ‘Mother Mary’, it feels complete.

Bloom Forever is out on May 6 via Stolen Recordings. Thomas Cohen plays the Moth Club on March 7; for full details and tickets, head here