Matthew Ingram, aka Woebot, is an author and researcher in countercultural history. He found his way into a wider study of countercultural activity from a start as a music journalist covering domestic avant-garde scenes like Jungle and Grime. His first major book, Retreat: How The Counterculture Invented Wellness (2020) looked at health methodologies like Transcendental Meditation, LSD psychiatry, and macrobiotic food.

Its sequel is another first-of-its-kind investigation into the generation that took LSD, went back-to-the-land, grew organic food, and pored over The Secret Life Of Plants. His book, The Garden: Visionary Growers And Farmers Of The Counterculture, is published in April, and looks at how with phenomena such as permaculture, the natural farming of Masanobu Fukuoka, and deep ecology, the counterculture set the template for the sustainable agriculture of today.

Ingram is, like many recent converts to the horticultural arts, a keen gardener. However, it’s compost itself and the dark arts of making soil which has caught his imagination, as much as growing itself.

My journey into compost

Gardening is a voyage of discovery. Once I had nailed growing seeds into seedlings, and had successfully planted them out in a raised bed, I looked around to see what else I could try my hand at. Shop-bought compost, the good stuff like Dalefoot, Moorland Gold, or Carbon Gold, is very high quality but expensive. So rather than waste material from the garden or kitchen, it’s thriftier, and frankly more fun and interesting, to turn it into a useful growing medium.

Composting 101

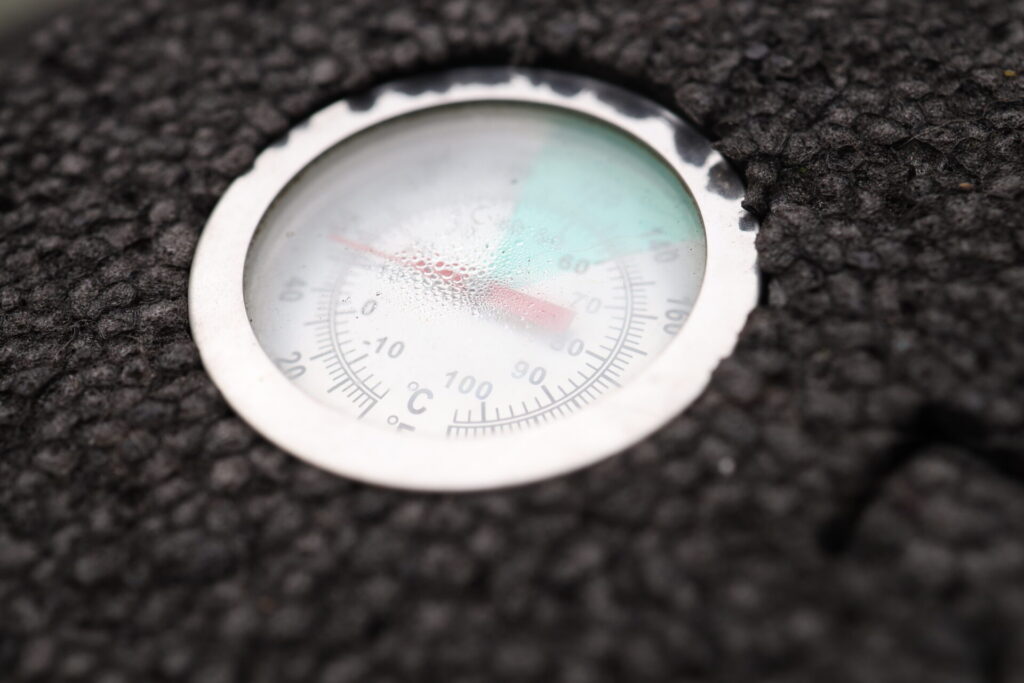

Whenever I think of compost my mind wanders to The Fast Show and its character “coughing” Bob Fleming and his “Country Matters” spot. But compost is a deadly serious business. I started doing it on my urban roof terrace in 2023. In layers you combine “green” matter rich in Nitrogen (not technically green this can be uncooked vegetables and any fresh garden waste) with “brown” matter rich in Carbon (fine woodchip, shredded cardboard, and paper). In the presence of oxygen, thanks to the action of bacteria, in its thermophilic stage the temperature soars, and the heap (in my case a Hot Bin) steams like an ocean liner. Composting does actually give off Carbon Dioxide, but see it as a net positive process, at the end you are left with a dark rich humus which is an ecologically valuable suppository of stable carbon. The simple trick to identifying the presence of carbon in soils, typically a residue of decayed organic matter, is the soil’s darkness. If soil, a field for instance, looks black or dark brown then it will contain a high amount of carbon, possess a high fertility, and be alive with healthy microorganisms.

Compost in history

Researching my book The Garden I ended up learning a lot about the history of compost. The process is mentioned as far back as the Roman Cato the Elder’s “De Agri Cultura” in 160 BC. However, with the increasing reliance upon first guano, seagull shit from the desert coastline of Peru in the 19th century, rich in macronutrients which are rocket fuel for plant growth – and then subsequently the widespread agricultural use of Sulfate of Ammonia created in the Haber-Bosch process, mainstream growers and farmers seemed to forget about the value of applying organic matter to the soil. Whether it was properly composted animal manure or made from agricultural waste and applied to the fields, the resulting soil, the plants themselves, and the environment are healthier than when doused with chemicals. Britain’s organic movement with its luminaries, the swashbuckling Lady Eve Balfour and implacable foe of “the NPK mentality” Sir Albert Howard, put compost at the centre of their rebellious opposition to Industrial agriculture. Howard’s Indore method, devised in collaboration and under the watchful eye of Indian farmers, produced what might be seen as the “haute couture” of compost – even if not regularly used by organic farmers in the UK the Indore method was a valuable organisational principle for the organic movement.

Composting in the Inner-city

I didn’t expect that my composting would smell and upset my neighbours. However, without enough circulating air the process turns anaerobic and does create a pong. One has to be sure that sufficient oxygen is penetrating the pile, to which end last year I drilled holes in a copper plumbing pipe and plunged it through the stack. That did the trick. The only persistent pest is not rats (that’s why one shouldn’t be in a hurry to compost scraps of meat or cooked food) – but our black cat Kiki who positions herself on the bin’s top, now having clawed its sides to shreds. No matter, it still works, and the resulting compost has produced many fine crops like these my winter brassicas.

The fine art of composting

I wish I could pretend to be a master composter. I visited the legendary Charles Dowding at his Homeacres garden in Somerset in 2022 and marvelled at the quality of what he is able to produce in his huge, roofed bays from an abundant supply of garden waste. Compost, and its application as a surface mulch, spread like marmite on a slice of toast, works brilliantly in a no dig system. Not digging the soil preserves its natural structure, doesn’t disturb soil microorganisms, and keeps the fine threads of mycorrhizal fungi intact. Composting at this rarefied level takes on a Vedic, cosmic dimension as a dramatisation of the cycle of life.

Compost as a process in culture

I came to gardening from a background of music. And there are unmistakable connections between the practices. The mix, like the creation of a good compost heap, requires carefully-selected ingredients – and only when everything is in the right balance will the alchemy occur. As WOEBOT I made a number of sample-based EPs and LPs – highlights being Moanad (2010) and Chunks (2011). These were made from the discarded remnants of seventies rock, whereas now I’m working with weeds, kale stalks, and the brown-paper packaging from deliveries.

Compost as our salvation

I’ve mentioned compost’s high seriousness. And, truthfully, its ecological importance can’t be underestimated. We throw away, as though it were rubbish, a truly disgraceful amount of organic matter. It is piled up in municipal rubbish heaps, burnt, or in the case of our “humanure” flushed out to sea. The Chinese civilisation, the “Farmers of Forty Centuries” that Professor F.H. King studied in his landmark book of 1911 would have been appalled by our neglect of this valuable resource. We forget at our peril that the soil which grows all our food is a precious and rapidly diminishing resource.