The tape recorder is an instrument

It all started before and during my time with Cabaret Voltaire. At the time I wasn’t aware of it, but my parents buying me a tape recorder when I was 11 was the trigger. It was a battery-powered portable tape recorder. I recorded everything in the house, and I realised that with batteries and a little microphone you could take it outside, and that was really liberating. Then I got into manipulating and listening back to it, it became a way of tuning in. Then I gradually became aware – this is the late 1960s and early 70s – of musique concrete. There’s this fantastic book I remember, I’ve still got it upstairs, called Composing With Tape Recorders. I’d got a tape recorder and I was interested in the idea of applying things musically, and I couldn’t believe it, that a grown-up had written this book. That got me interested in the idea of using the tape recorder as an instrument.

Natural history programmes used to be as frustrating as bands

Back then, what I was hearing on natural history programmes, particularly the British ones, was nothing like the reality of what I was hearing out there, particularly through my microphone, even though it was very unsophisticated in those days. Programmes then were plastered wall-to-wall with the most ghastly music. I thought: "This is really shit, we can do a lot better". It was one of the things that really prompted me to work in that media, because the standard was so dreadful, it didn’t represent the places. It was just like music videos really. That was the cue, to think "I can do better than this". I began to do that, and gradually as I got to know filmmakers and trainee producers who were starting out, we went along career-wise, and as it went on I could convert them into this way of thinking – and it worked!

There were some really challenging situations to record sound in

There’s a caterpillar which has a symbiotic relationship with ants. These ants find the caterpillars in the woodland, and take them back to the nest, primarily to predate them. But in fact the caterpillars produce a sound inside themselves which forces the ants to feed them, it’s an incredibly bizarre relationship. The challenge was to record these caterpillars making this sound which stimulates the ants to feed them. This is only really done inside the ants’ nest, and so I was working with an organisation called the Institute Of Terrestrial Ecology who have developed a recording technique using something called a Particle Velocity Microphone, which is basically like a super compact microphone.

The worst thing we suffer from in most places on the planet is noise pollution

Obviously sometimes you need to incorporate the sounds of a place, but a lot of the time a lot of the things I focus on are drowned out by noise pollution. There’s a place in India which is one of the most beautiful sonic locations on earth. It’s a reserve, in the foothills of the Himalayas. It’s not over-flown, so there’s no aircraft noise. Secondly, because it’s a reserve and managed with a Hindu philosophy, they have a great respect for everything in there, all the plants and the animals, and tourists aren’t encouraged to go in. This place is the size of Greater London, and they allow 40 vehicles a day to go into it. Imagine that – you’re hardly likely to bump into anybody. It’s one of the most undisturbed places that are left on the planet. Because of this it has this incredible depth and atmosphere to it, you can record and almost uniquely listen into the background, and hear things in a way that you hardly ever get the opportunity of doing.

We’re all damaged by noise pollution

…psychologically as much as anything, and we’re just not aware of it. You ring your bank and they play music at you down the phone, it’s so invasive. Because of that we waste so much energy in shutting things out, we don’t get the chance to listen. I do find it really quite annoying and disturbing. I’m saddened that people have to battle through this or seem to ignore it. It’s a stressful thing to deal with it, that you spend most of your time and energy shutting things out rather than listening.

Background sound is far more offensive than any of the ‘noise’ we made with Cabaret Voltaire

I remember pubs and bars where you’d choose to go because you liked what was being played, and you didn’t mind raising your voice to have a conversation in that place, because it was a good atmosphere. It’s the meaningless stuff that I really dislike, and also the appalling state of architectural acoustic design. The advent of cheap fabricated buildings means that most of those that you go in have such appalling acoustics. You can’t have a conversation or you can hear everybody else’s conversations because you’re surrounded by flat parallel walls.

When I see a painting, I hear sounds

Creating a soundtrack to Constable’s The Cornfield [listen here] interested me because it’s static. What engaged me there was perspective, because I use sound perspective a lot. I was balancing sound perspective a lot, because that’s what Constable did. You can come in and close your eyes and you’re still there.

The Christmas dinner has use in sound recording

I wanted to test some new microphones, so I staked out a turkey carcass in the garden. You can hear the beaks of the starlings against the bones.

I like that aspect of fishing for sound

I’ve been to the North Pole, and tried to get the sound of the spindrift, which is the ice crystals being blown across the frozen sea. I had to construct a strange little rig to put on the ice. It wasn’t quite successful. But I like messing about like that. There’s no point standing there holding a microphone for most things that I do. You’ve got to work at it, and use it like an acoustic lens. I mic’d up a flower to get a bee pollinating it, which is something I might come back to in the summer.

I don’t see the work for television and radio as separate from installations

I see myself as a sound recordist. The great thing with sound is that you can work across all these mediums. All my camera colleagues are restricted to this two-dimensional thing, they work in feature films or televisions and that’s about it. Sound you can transcend all of those, so I do stuff for Touch, I do installations like this, I do television documentaries, I do radio, which I love, and I do stuff for computer games, which is fantastic. Really interesting stuff. You can do all of this. I really like weaving my way between them, and one thing often informs another. I made Cobra Mist, a film with Emily Richardson, a couple of years ago. It’s about Orford Ness, the old weapons testing range. I thought it was such an amazing place that I talked to the producer I work with at the BBC and we made a radio documentary about it. So none of these things are in isolation. I don’t delineate between Chris Watson artist and Chris Watson sound recordist. That’d be pointless. You just need to keep your ears open to possibilities.

I’m aware that there’s a wider political aspect to my work

…but it’s not my job to lecture. People need to decide for themselves. The better informed you are then you can start to realise what’s happening. If the plants go, it will be a silent world, so there is a message in that. But I’m not a scientist so I don’t lecture, but I am well aware that the more you know about something, the more likely you are to be concerned about it, and to do something about it.

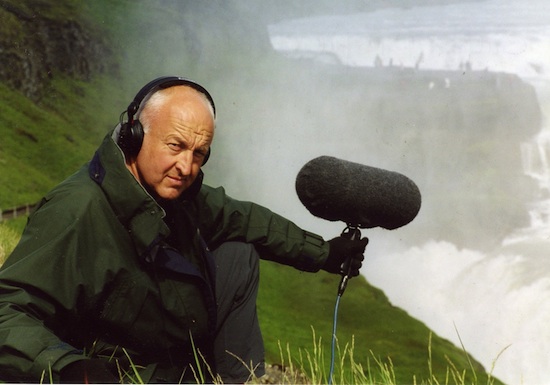

No-one else can hear the world like you can when you put those headphones on

With nearly all wildlife and natural history work it’s a solitary process. You can’t talk about it when you’re recording, you’ve just got to move the microphones and do it. In that sense there’s an easy analogy with photography. It’s a solitary activity. I then like going through the process of selection, editing, composition, production, performance, whether it’s a radio broadcast or a sound installation, which you then share with as many people as you can to engage with them. I really like that idea of going from the point source. They’re all pieces of work, I wouldn’t want to do one or the other. That’s what I love about what I do… bloody hell, I get to do this! It’s brilliant!

Chris Watson is appearing at PLACE: Roots – Journeying Home, which takes place in Aldeburgh from February 1 to 3. Watson has created a series of soundpieces retracing the ‘composing walks’ taken around the area by Benjamin Britten. For more information head here, and for more on Chris Watson please visit his excellent website