After hearing the Headman remix of a song called ‘High Pressure Days’ on Relish records, I was stunned to find out about this amazing group called The Units who were operational between 1977 and the mid 80s. On listening to an anthology called History Of The Units (which gets a UK release via Community Library this week) I wanted to learn more about them.

What I found was a situationist group with an anti-fashion, pro-art manifesto who used to smash up fake guitars every night, make their own films, share stages with the Dead Kennedys and draw as much from punk as they did from their local gay disco scene.

When I got in touch with Scott Ryser in SF, he was kind enough to answer my questions – even the ones disrespectful to Devo.

We normally wouldn’t run a feature this length, even if the interview was with Prince but, you know, fuck it. I find it interesting and I hope other people will as well.

Looking at fliers for your gigs you seemed to play several times with The Dead Kennedys. How did you get on with the punks and their audiences?

SR: With that question you make it seem like it was a “them vs us” situation… which just wasn’t the case. We ALL went to each other’s shows back then. Most times the audiences weren’t any larger than 300 people or so… and they were all in bands. We even jammed with a lot with people from other bands… dare I say, even with guitar players. And band members would transfer from band to band like it was a game of musical chairs.

At that time in SF the term new wave hadn’t been invented yet and punk had not been rigidly defined. Punk wasn’t relegated to a guitar, black leather jacket, tight pants and safety pins uniform (although I wore those things sometimes).

At that time being punk meant being creative, artsy, anti-establishment, funny, daring, provocative, innovative… and most importantly, ORIGINAL. The bands people loved were the ones that DIDN’T COPY ANYONE ELSE! We were all those things, and for that reason we were well liked. The Punks at that time didn’t WANT us to be the D.K.s… They wanted us to be The Units!

You might see a show with the D.K.s, The Units, and Z’ev (just one guy on percussion)… or Noh Mercy (a woman singer and a woman drummer), on the same bill.

When the Dead Kennedys started, people in the scene didn’t just like them because they were a “guitar band”. People liked them because they were very creative and original and funny, from their “anti-fashion” down to their lyrics. Not only was Jello very political, he also had the ability to break down preconceived notions of the frontman formula and the audience/performer relationship. We could share a bill with them at that time because people weren’t looking for “punk uniforms”… people in the scene were looking for craziness and business-as-UNusual.

Did you get a lot of friction from the ‘synths aren’t real instruments like guitars’ crowd?

SR: Once again, the question doesn’t represent the situation.

It’s just not as simple as that. Because so much of the reaction we got when we started performing live probably had more to do with the openness and enthusiasm of the new punk scene in SF rather than the fact that we were a live synthesizer band. It was a scene that seemed to embrace innovation and originality on all levels.

While it’s true that we were the first punk band to perform in SF using just synths, and we were in fact anti-guitar, and you would think that might be controversial, nobody in the scene at that time seemed to raise an eyebrow over it. Had we started playing shows anywhere else, I mean, any other city, people probably would have been pissed and thrown bottles at us.

But I think because it was pre-AIDS, gender confused, sex & drugs San Francisco, where there were lots of people doing much weirder things than we were, that people didn’t seem to react any different to us than anyone else.

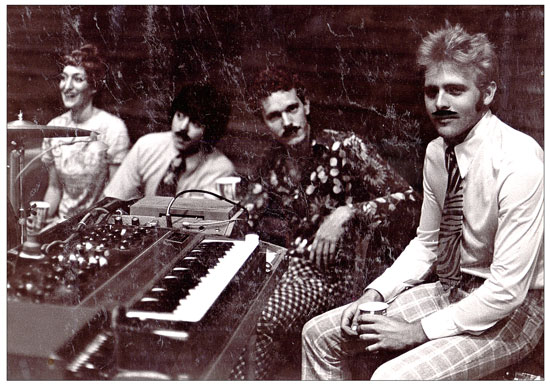

Here’s an example. In San Francisco, in 1978, when Ennis (Tim, synths, vocals) and I were looking for a new drummer, we went to check out this great drummer, Richard Driscoll, that eventually joined our band. Richard was playing in a gay cowboy club in a seedy district of SF.

This club looked exactly like something off the movie barroom set of Blazing Saddles, only with a transvestite playing the Madeline Kahn role. The club was packed full of super buff men wearing butt-less chaps, cowboy boots with spurs, big cowboy hats, handlebar mustaches, and, well… nothing else! They were all topless cowboys. And I can imagine that these cowboys were riding more than horses later that night. It was as if the photographer Bruce Weber’s best ever homoerotic cowboy dream had come to life in downtown SF.

This wasn’t some one time Halloween Ball kind of event. This club had been open every single night of the year for years!

What I’m saying is that most of the audience was focusing more on butt-less chaps that they were on whether or not I had a guitar or not.

Now, I think if we played at a real cowboy bar in Wyoming at that time, I might still be trying to put the pieces of my Minimoog back together. But at this exposed buttock bar it was a different story.

I remember sharing a bill with the performance artist Karen Finley. She came out on stage naked and put canned yams up her ass. Nobody seemed to care that we were playing synths that night either.

And then of course Phillip from the band The Puds… nobody can seem to remember what instruments they played, but the crowd enjoyed them nonetheless, because the only thing they wore on stage was a single 7” record with their pud sticking out of the center hole.

I’m telling you, at that time, there was this kind of shit, and even BETTER shit, going on all over the city! People had way too many strange things on their minds to bother thinking about synths vs guitars. It just wasn’t an issue.

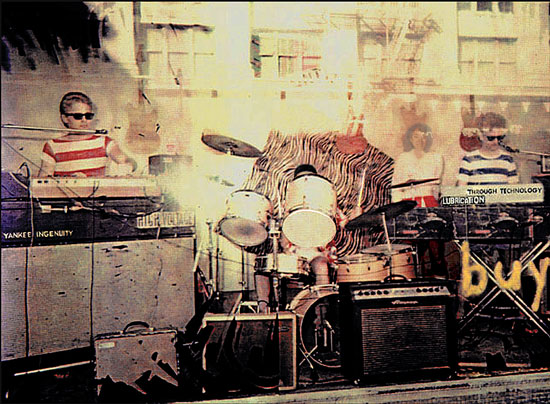

On top of that, when we performed we often had other things happening on stage, things that probably distracted the audience from focusing on the synths. For example, the first time we played with the Dead Kennedys, we set up this big movie screen we made from the metal hood of a Cadillac car on the stage, on a tripod made of wood 2×4s. We set our synths to play a factory drone sound all by themselves, then we projected images of hated politicians, products from obnoxious advertising photos, irritating authority figures and the like, we projected these images on the car hood, and then beat the hell out of them and the hood with lifesize guitars that we’d cut out of plywood. We made the guitars so that they would shatter on impact. Pieces went flying into the audience and they would throw them back up at the projections… we were lucky nobody got hurt or sued us.

That night Jello was diving into the audience… who stripped him… he ended up finishing the show naked.

I don’t think ANYBODY in the audience that night woke up the next day thinking “The D.K.s play guitars and the Units play synths.”

The Units have a very un-Californian sound. Were you part of a scene in the late 70s/early 80s or did you exist in splendid isolation?

SR: We were definitely part of the fantastic California art/punk scene back then. The scene was open to and supportive of a wide range of unique and unusual sounding bands. We played shows (and even shared members) with SF and LA bands like the Dead Kennedys, Crime, Tuxedo Moon, Screamers, Voice Farm, Mutants, Go Gos, Romeo Void, Offs, and many others. The synth player from the SF band The Tubes produced a couple of our songs and Prarie Prince played drums on a few of them. We also played shows and shared a drummer with the (now) film score wiz Mark Isham and Patrick O’hearn when they were playing in Group 87 in the Bay Area at the time.

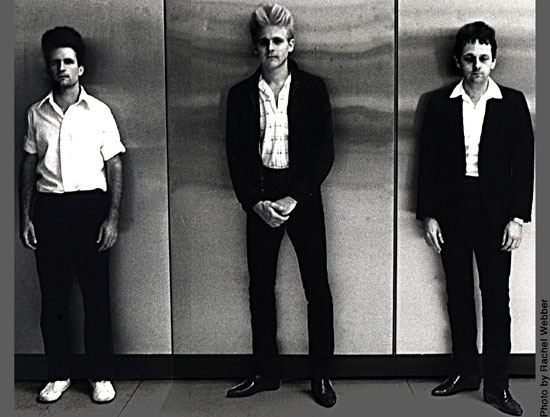

On top of that we did a lot of performance art collaborations with the likes of Karen Finley, Tony Labat, Tony Ousler, and others. We played in the windows of downtown JC Pennys there, played the National Anthem at a “(real) boxing match for artists” at Kezar Stadium. Rachel (Webber, synths and vocals) and I showed our Unit Training Film at local movie theaters, and were involved with local experimental film makers like Bruce Conner who was living there.

In fact, it’s interesting that at the same time the synthpunk thing was happening in LA and SF, you had the League of Automatic Music Composers working on experimental electronic music across the bay in Oakland, at Mills College and an American experimental music tradition, as represented by fellow Californians John Cage and Henry Cowell among others.

Part of this California electronic music tradition also included Terry Riley who studied San Francisco State University (where I went), and the San Francisco Conservatory (were several of the Units drummers went) before earning an MA in composition at the University of California. Terry was involved in the experimental San Francisco Tape Music Center working with Morton Subotnick, Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros, and Ramon Sender. All of these people influenced us more that the English bands we shared bills with.

So you can see, although we may have had a unique sound, we hardly worked in a vacuum or without a rich electronic musical tradition.

You certainly had more of a European sound than a band like Devo for example – you were a lot less zany or frat boyish – was this a pro or a con do you think?

SR: I think Devo has a larger cultural imact than reducing them to "zany" or "fratboy". Along with being lots of fun, their music and vids were great satiric commentary on our culture. Especially in the beginning. We were already playing shows in the late 70s when I first heard of and saw Devo live at the Mabuhay in SF. My first reaction was “Shit, they are doing kind of what we are doing, only they are better at it. They have perfected the black humor critique of how our culture worships conformity and technology.”

I think Devo took a more funny approach than us, and they were able to critique art as commodity… while still making money off it as a commodity! Kind of like Jeff Koons, they packaged their critique in a great pop culture way, and frankly, the packaging helped it sell better to the masses. We took a weirder, more alienated, “outsider art” approach to it.

I continually struggle with the idea of the relativity of things, and of the parts of something versus the whole of something… and whether or not you feel the part that you are playing in that whole is helpful, valid, or rewarding. So to me, it’s hard to reveal an artistic revelation about our culture and just present it as humor.

I envy Devo for it’s simplicity.

I’m just too neurotic and obsessive to be like that. For me, there has to be a more frightening element to humor. Devo was able to accomplish many of the same concepts we were trying to convey… only they weren’t as confrontational, their humor not quite as dark, and they didn’t weird people out in the process, as the Units were apt to do. We were just different, and perhaps more self-indulgent in our instrumentals. But I have nothing but respect for what they accomplished.

You seemed to support a lot of European bands who came over such as Numan, OMD, Soft Cell, Ultravox, etc. Were these bands that you felt a kinship with? Did you get on with them?

SR: As far as the European bands we played with, I was happily entertained by all of them. I love just about anything synthesizer. Andy and Paul from OMD were great guys. Numan’s ego was a bit much, but I loved his music. I enjoyed the music of all the other English bands that we played with too. I consider them all pop bands… but unlike what most people would assume about me, I happen to love a good melody and a good pop song. Especially a synth pop song. I respect anyone who is able to do it… contrary to popular belief, it’s REALLY hard to write a good pop song.

Just because ‘love’ has been commodified and overused as a song lyric doesn’t mean that it isn’t one of the best things on earth. I’ve been married to the same woman for 30 years, have kids, and have lost parents, dear friends and beloved pets… so I know about love… and would have absolutely no problem writing a song about it. Unfortunately for me… it would probably have some dark bent to it that would disqualify it for “music to have sex to”!

The short answer to the question is that I was quite happy just sounding like the Units. I had no desire to be like Devo or the English synth bands… even though I liked them both. If you forced me to listen to any of them now though, I’d probably put on the Limeys. They tend to be more complex and dark.

Despite playing synths you had a very definably punk rock attitude towards things like selling-out and upsetting the apple cart, didn’t you?

SR: We were rebelling against the status quo… against the formula of pop music. We were trying to break down preconceived notions of the "audience/performer relationship" and preconceived ideas of what pop music and performance should sound and look like. Weird I know, we were artsy, and yet against the formal institution of the musem-art-world acceptability at the time. Remember, it was DIY… not DIY after you have been trained in an institution how to be DIY. And I think that’s why the synthpunk scene fitted in so well with the performance art scene in SF at the time. Because in the mid and late 70s performance art was challenging preconceived notions of institutional art.

Can you tell me what the guitar meant to you as a symbol and in reality? What it represented to you in theory and how you used to convert this to a practical part of your stage show with the cut out guitars?

SR: I liked watching Pete Townshend smash his guitar during old footage of ‘My Generation’. But at the same time I thought, “Fuck your generation, Pete, if all it’s going to do is smash guitars on a stage instead of on Margaret Thatcher’s head.” I wanted MY generation to take it a step further. Do you see what I’m getting at here? I have nothing against Margaret Thatcher personally, but you know what I mean? There are PLENTY of things to be angry about… why not point a few of them out! If you are so angry that you feel like you have to smash a guitar, why not do it on an image of George Bush! So that’s what we did! We weren’t just putting on some show… we were pissed! Our country is made up of an exclusive, white, corporate, good-ole-boys club of rich bastards… fucking the millions of the poor! Raping the earth and trying to strong arm third world countries out of their natural resources. What did you want us to do? Sing ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” like the Beatles?

I don’t have anything against guitars as a musical instruments. But it annoys me that in popular culture, many musicians and the music industry have taken the good intentions Woody Guthrie had with his guitar, the one with "This Machine Kills Fascists" written on it, and turned the future of it into a commodity and a fashion statement. They have homogenized the piss out of it until it might as well be the symbol for Coke, Budweiser or Marlboro. The USA media is great at taking confrontation and dissent against the status quo, and repackaging it, and selling it back to the masses as sex, entertainment and fashion.

That’s what happened to the guitar heroes. It’s all just posing now. I felt like in order to make a new statement of dissent, I would have to accompany it with an instrument that didn’t come pre-tagged as a symbol of sex and entertainment.

We cut out the stacks of plywood guitars and smashed them on the metal Cadillac hood that we were using as a movie screen, not only because it sounded like a big gong, it was like smashing the auto industry and the music industry and at the same time saying “We’re tired of all the lies and bullshit you’re selling us."

The guitars were a convenient symbol. That’s all. A lot of people still don’t get it. Including my own kids!

Did you have that thing of people saying that synths couldn’t be heavy despite having really booming songs like ‘Contemporary Emotions’?

SR: No. At least not live. I played keyboards in a hair-metal band in high school. I knew how Hendrix, The Who, and Zepplin got their music to sound heavy. I applied the same processing to my synths as they did to their guitars to make it kick ass.

Fuzz boxes, echoplexes, big tube amps… I’ve never heard a guitar that sounded any better than my live gear set up.

I first heard The Units on a Relish Records compilation this year. The song ‘High Pressure Days’ had been remixed by Headman. But even on hearing the original it was quite obvious that The Units must have sounded very futuristic when the song first came out in 1979, very forward looking back in the day. How did you get involved with Relish and this current crop of remixers?

Scott Ryser: I love the idea of remixes. It’s a very punk idea to me. I love the idea of reconfiguring art and technology and taking it to places that it wasn’t intended to go. Like Sid Vicious covering Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’. It can be very funny and ironic. Like graffiti, but in a musical way. It opens your eyes to concepts you take for granted and it makes you re-think why it is you like things in a particular way.

I love the way Tom Ellard from the Severed Heads takes TV commercials and “remixes” them in funny ways. It seems like remixes are usually reserved for disco or dance songs. I don’t really consider The Units disco artists, but I love it when people remix Units songs for the dance floor. I also like hearing ideas that I hadn’t thought of or was incapable of doing well myself.

The people that were the first to start re-mixing the Units were actually some of the cornerstone trailblazers of the Italo Disco scene way back around 1980. The legendary Italian Cosmic DJ Daniele Baldelli started re-working our songs way back in 1979 and the early 80s and was responsible for giving us an audience in Italy.

This is very interesting to me, because while in the USA, the punk scene that the Units were part of in the late 70s was rebelling against the conformity and regimentation of disco, some forward thinking Italian DJs were taking a very a different approach… instead of killing disco with a new genre of music, they just punked-up disco.

I’ve always loved the creative, outrageous and funny, gay club music scene in SF, especially in the pre-AIDs era. Many times it had a better sense of humor than punk. Those gay dance clubs were definitely anti-institutional. The best remixes to me are similar to graffiti, in that they re-direct the message, like a guerilla artist might do by spraypainting a different subversive message over the original of a corporate advertising billboard. Or sometimes, just bringing out the potential soul of a song.

In the early 80s, Baldelli would take a disco dance song, but play it at the wrong speed and then add weird space effects to it. He’s got to be one of the pioneers of the mashup too. Playing slowed down Units songs on top of contemporary Disco. His style became so popular in Italy that people started putting out 12” bootleg records of Units songs “to be played at slow speed”, with the instructions written right on the record label. I can’t help but laugh when I hear them. My voice sounds like Darth Vader from Star Wars. It’s great.

As far as the recent 12” remixes; Robi, (Headman), had been trying to contact me about licensing ‘High Pressure Days’ for years. He finally tracked me down and (since I like his music) agreed to license the song to him for some remixes on his Relish Label. He did a mix, and Rory Phillips from London (my fave remixer at the time) did a mix. I love both of them.

Tell me about your front man formula please.

SR: We wanted to de-emphasize the “front man formula” that most bands have. Where some guy’s charisma (or sex appeal) is more important than the message. That’s half the problem in life. People idolizing some guy’s glowing image. Be it political, religious or military. Putting all their faith into some front man instead of looking behind the wizard’s curtain and taking care of business themselves. That’s why we projected the films and didn’t spotlight ourselves. We even spray painted all of our equipment battleship grey to get rid of the distracting corporate advertising logos.

I guess when it comes right down to it, humans are herd animals. We want to follow somebody… even if it’s off a cliff. I guess I’ve softened in this viewpoint in my old age… at least when it comes to entertainers. When it comes to entertainment, maybe you can’t blame us for swallowing the frontman drug after a hard days work. Life can be hell sometimes… and it helps to be medicated.

Did you have the same influences that the UK synth pop bands had – i.e. German music especially Kraftwerk and confrontational art acts such as Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle?

SR: Kraftwerk no. Not back then. Back then I’d rather listen to the motor of my car than to listen to Kraftwerk. What can I say? They were fucking boring back then. The scary thing is, now that I am getting old… I’m starting to like them.

I do like what I’ve heard of Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle. Especially T.G. However I’ve only listened to them recently. How can you not like the Chris & Cosey story. Somebody should make a film of it.

The fact is, I was trying to sound different than everybody back then. The most horrible thing I can think of and the last thing on earth I would want to do is to sound like somebody else! WHAT’S THE FUCKING POINT OF THAT?

One of my not so “famous” contemporaries in the SF scene, and somebody who actually DID influence me was the percussionist Z’EV. He’s a real original, and he summed up my feelings on this question perfectly by saying this: “It’s bad enough that I have to compose music, don’t expect me to waste any more precious time listening to it.”

Do you think bands such as The Units prefigured the totally anti-rockist movement of rave and acid house?

SR: I don’t know. All I know is that I really enjoy listening to rave and acid house. Love it. Especially in a big space.

Can you tell me the story behind the name The Units please?

SR: We got the name from a drooling, lunatic, mental patient by the name of Carl Yorke from Novato, California. Actually, Carl was only a lunatic five nights a week and on Saturday afternoons. You see, he played Ruckley in a production of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. You know, the character with the bald head that leaned against the back wall of the mental institution, drooled, and frequently yelled “Fuck ‘em all!”

Acting strange was in Carl’s blood. His grandpa had a vaudeville comedy act called “Potash and Perlmutter”, and Carl was keeping up the tradition. He later moved to New York to be an actor and then a reader for a publishing house. I think that years of spending most of his waking hours playing the role of a drooling mental patient had given him the equivalent of a drug induced hallucinogenic epiphany. It had put him on the outside edge of the human race with the other crazies, where he was able to get an unobstructed view of “normal” people and our conformist, consumer driven culture. When I met him, it seemed like the only things left rattling around in his brain were “Fuck ‘em all” and “units”. His obsession with insanity and seeing people in our culture as “units” was contagious, and once I became infected with the idea I couldn’t seem to shake it either.

In retrospect it seems only natural that Ken Kesey’s driving Carl crazy is somehow responsible for our band, the “Units”. I don’t think you can underestimate the influence Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters (chronicled by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test) had on the anti-establishment, prank driven, California punk and performance art scene in the ‘70s. I liked the way Kesey had kept a sense of humor and a prankster mentality while questioning institutional authority, but what was really interesting was the way he and Tom Wolfe, through acid trips, had taken a look at the human race from a real outside-the-body viewpoint. The shamen or spiritual leaders of various indian tribes and cultures throughout history had taken mind altering drugs in order to see the unseeable, but it had been quite a dry spell in America when Kesey and Wolfe experimented and wrote about it.

At any rate, Carl had put a name on something I had been spending a lot of time thinking about anyway, and I didn’t need to take acid to see it.

From the perspective of social outsiders… confined, drooling, mental patients, we came to see humans and their environs as one dimensional units operating in a predictable clockwork machine. The Units name was central to most of what we were trying to comment on in our music and performances. To me, it represented the thinking process our culture had chosen.

We think in unit like words and numbers and time, each unit separate and distinct, like little shrink wrapped products. We think by separating things, by breaking wholeness up into distinctions… and then often disregard or forget the interconnections that had existed between those things. We chop up the timelessness of cycles by creating one-direction timelines and putting a beginning, middle and end to events. We take things out of context and categorize them.

Instead of thinking in a holistic way we have created a box like thought structure with straight lines and squares, things that are extremely rare in the natural world. We think with box like ideas and build our houses that way too, with walls that protect us, but at the same time separate us from the sea of life outside. We now know that the world is round, but we still think as if it were square. Assembly line mass-production, with it’s distinct yet identical products that seem to come from no natural source, only reinforces the idea of units. As does our strict adherence to the hours, minutes and seconds of time, breaking up the flow of our lives into segments, whether it be for work or the convenience of media programming.

The concept of “units” is like an artist’s creation, at some point way back in the beginning we made all of this up. We chopped up wholeness into units to take a closer look at it, and we never put it back together. The unit-like way in which our culture thinks seemed omnipresent and pervasive to me. At the same time it felt at odds with a more flowing, interconnected and symbiotic realty.

Did your proximity to silicon valley feed into the use of synthesizers and technology?

SR: Without a doubt. I felt like a surfer that was riding the crest of a giant techno tidal wave.

Can you tell us about your use of films and projections?

The Unit Training Films, produced by Rachel and I, were films that the band projected during their live performances. The films were satirical, instructional films critical of conformity and consumerism, compiled from found footage, educational and industrial training films, home movies, obsolete instructional shorts, with a dose of soft porn. In 1979 and 1980, Rick Prelinger was a frequent contributor and occasional projectionist at the band’s live performances in San Francisco. As I said before, the original intent was to take the focus away from the “front man formula” and to “re-direct” institutional training into a fragmented and subversive direction.

There was never a set length or definitive “finished version” of the original Unit Training Film. Just the current version. The film varied in length from about 10 to 45 minutes, depending on how long the Units set was on any particular night. Clips were constantly being added and others were deleted and discarded once their condition became too poor to project any longer. The film was constantly breaking, and the projectionists always kept a roll of Scotch Tape nearby for timely repairs.

Should you feel that you haven’t just learned enough about The Units there’s plenty more at SynthPunk.org.

The fabulous History of the Units is released today on Community Library Label from Portland, Oregon. The compilation Connections that features Units tracks remixed by 30 DJs, bands, and producers, on the Opilec Music label from Italy, is due out in January next year.