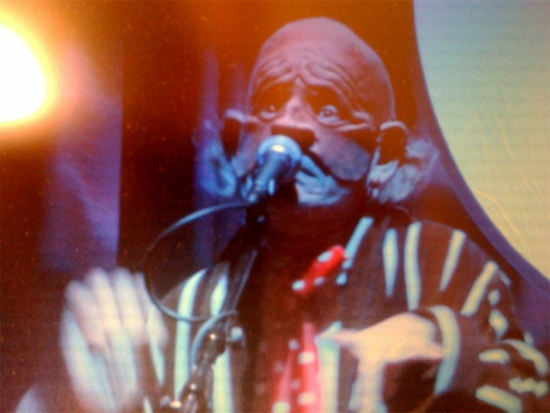

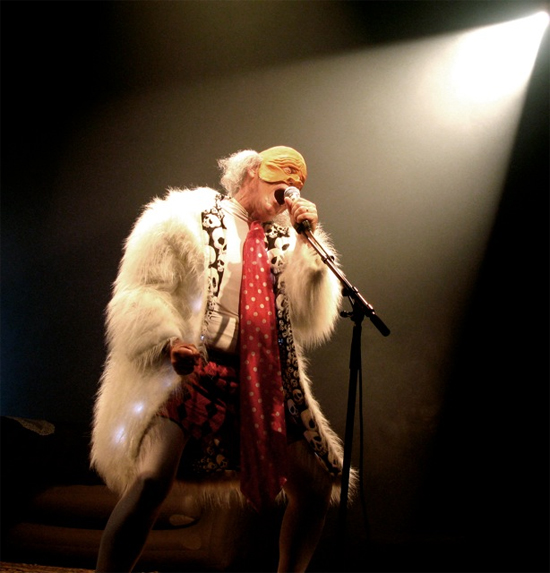

Oh, isn’t it always so nice to spend an evening at Grandpa’s? The fire is burning, the telly’s on, and Grandpa’s sat on the sofa with his feet up on that old rug of his. But… Hang on a minute. Something’s not right. Was Grandpa’s tie always that absurdly big? And why is he wearing those horrible old long johns and – are those clown shoes? And why is the TV only showing static? Now Grandpa’s dancing like a skeleton in an old cartoon, or a demon in a painting by Heironymus Bosch. And his face, his skin, it… It doesn’t just look old. It looks hideous. Like a Venetian carnival mask, or like Davros, emperor of the Daleks. And it sounds like there’s some kind of rave going on next door. Who are those other men with those black masks? (Are they even masks?) They’re scaring me. And Grandpa’s voice! Oh, Grandpa! Stop screaming! It’s horrible! So deep, and resonant, and reverberant, like the sound is never going to end! Oh, stop it, Grandpa! I can’t stand it!

The Residents, let us be clear about this, are not a band. They never were. At least, they would not call themselves a band. They probably wouldn’t call themselves anything. They didn’t even call themselves The Residents. The story goes that in 1971, the band recorded 39 songs, christened the collection The Warner Brothers Album (complete with the Looney Tunes logo on the sleeve), and sent it – unsigned – to Captain Beefheart’s merchandising director and WB executive, Hal Halverstadt. Appalled by what he heard, Halverstadt promptly posted the tapes back to the return address. Without a name to identify the product, he addressed the parcel to ‘The Residents, 20 Sycamore Street, San Francisco’.

When pushed, The Residents’ spokesperson, Hardy Fox, will refer to The Residents as "a group of people who work together based on shared ideas rather than their craft with a musical instrument." Proud non-musicians when the group formed, they were always of the opinion that originality was assured if they taught themselves how to play their instruments, developing their own idiosyncratic technique as they went along. Imagining some possible music from scratch has been more than just their modus operandi; at times it has been just as much the explicit content of the group’s work. The Mole Trilogy, a three album saga from the early 80s, posited a kind of ongoing class war between the "Moles" and the "Chubs", each identified by their own distinct stylistic sonic signature, while Homer Flynn of the Cryptic Corporation said of an earlier attempt to imagine the music of the eskimos that the record "could have been on Mars as far as they were concerned."

"Hello everybody!" says the gurning, hunched over figure on stage who is not my grandfather. "I’m Randy, the lead singer with The Residents." He spreads his arms wide in a gesture equal parts lyric tenor and pantomime dame. Having introduced instrumentalists/Sylvestor McCoy-era Dr Who baddies "Chuck" and "Bob", our host goes into the first of tonight’s ghost stories. In a pitch-shifted southern drawl, Randy tells of sinister talking lights, haunted prairies, and, "worst of all", the mirror people, over a backing of howling drones and skittering rhythms, spectres of drum & bass and rock n roll drifting somewhere in the background. Slurred synths bend like Badalamenti, but the overall effect is less Twin Peaks than Tales from the Crypt. Weird tales told from the fireside for a generation weaned on backyard barbecues and the bomb. The Residents, Fox insists, are into the "disposable" side of American culture: Hank Williams and Frosted Flakes. "There is no necessity to take music terribly seriously while you are being totally serious about it."

Homer Flynn and Hardy Fox are now the sole partners in The Residents’ management company, The Cryptic Corporation, following the 1982 departure of Jay Clem and John Kennedy (not to be confused with the 6Music DJ). But despite persistent denials (repeated in the course of my interview with Fox), many have suspected the pair of being members of the band, if not the band tout court, a speculation only heightened by the presence of Flynn and Fox’s names as credited authors to all the group’s songs, according to the BMI’s online database. Looking back over old interviews, one finds Fox frequently tripping himself up over pronouns: one minute the band are "us", "we", "our", the next he will correct himself to "them", "they", "their".

The confabulation of imagined identities and (possibly) fictitious personages seems to be just as much a part of The Residents’ career-long strategy as the invention of imagined musics. Official band histories cite their mentor as being a certain obscure Bavarian composer and musicologist called N. Senada (or "en se nada" perhaps?). Senada is credited with two theories that have come to stand as guiding principles for Residents practice ever since, the "Theory of Obscurity" which states an artist will always be at their most creative when divorced from the recognition and feedback of an audience; and the "Theory of Phonetic Organization" which demands that music should be built up from the sounds themselves, rather than leaving them as a secondary afterthought after rhythm, tone, structure, etc.

In light of the latter, it may come as some surprise that a great deal of the group’s more recent work seems intent on pursuing a sound palette that is perhaps best described as ‘General MIDI’. Even more damning, the show betrays signs of real musicianship, "Bob" spits out guitar chops that wouldn’t be so out of place on a Joe Satriani record, even if here set against a background of tense tonal undecidability. "Culture has changed in ways not anticipated," claims Fox. "Life requires flexibility but a manifesto is a good way to understand what it is that you want to do when you are starting. We should all write them when we turn twelve." A curious statement which half implies dismissal of the first three decades of The Residents’ work as mere juvenilia. The new Talking Light show doesn’t feature any songs from albums more than a decade old, nor, when asked to pick a favourite album does Fox stray any further back in time (in order to "defy" me, he chooses both 2005’s Animal Lover and 2009’s The UGHS!): "The Residents do not live in the past."

If the past is another country, the future is equally inaccessible – Fox declares he has "never thought about" the future of music. The Residents, he says, "are live people who are working in the present." And the present in question is evidently a technological one, in which the ghosts are decidedly ex machine. This has led in the past to the fulsome embrace of every faddish format going, from laserdiscs to CD-ROMs, hailed as pathbreaking innovators at the time, such choices may be more questionable in retrospect. Today they are offering "special nods to Apple." Is there a contradiction in such a supposedly countercultural entity giving props to one of the most powerful multinational corporations on the planet? Perhaps not, for a group which gives a kind of structural equivalence to the "American Revolution of 1776 and the Summer of Love revolution of 1967." The Residents have always presented themselves as an at least semi-ironic corporate behemoth, while their contemporary 68ers were busy building real world-conquering corporations.

"We all live with ghosts everyday," insists Fox. "Everyone does and everyone always has." Against the translucence of the ghost, The Residents offer a sealed off obliquity (when I ask what led to the "ghost story" format of the present show, I am told obscurely "that is something that will become clearer in time. For the moment I’ll just say it is not the whole story") – an attitude which seems to conflict with their professed admiration for "the structural ideas of Gustave Eiffel", for whom deep structure tended to be presented directly on the surface. But then perhaps the Eiffel they so admire is not the architect of the Parisian Tower, hymn to the industrial revolution, but of the Statue of Liberty, beacon of American liberalism. The Residents "view the USA as a wealth of eccentric personalities" in which "everyone has a story worth telling." Which is all very cosy, but distinctly ideological in an era of rapidly growing inequality and continuing imperialist foreign policy.

On an album Hardy Fox lists as an inspiration to the band, Two Steps from the Blues, Bobby Bland sings: "It is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all." The Residents have always inspired a cultish devotion, the passionate dedication of the converted, and their missteps will always be a million times more interesting than the finest products of most other artists. If their clammy embrace of the internet interactivity sometimes comes across like Granny’s attempt at textspeak, well perhaps that’s all part of the fun. And if nothing else, the Talking Light performance certainly is a fun show in which only a very small proportion of the audience’s laughter is nervously forced. There is a certain sense of the transitional about the group at the moment, a little filler before the killer. But as Fox reminds me, "The 40th anniversary looms in 2012. We will just have to see what they come up with…"

The Residents appear at the Mute Short Circuit Festival, held at the London Roundhouse this weekend. For tickets and more information, go here