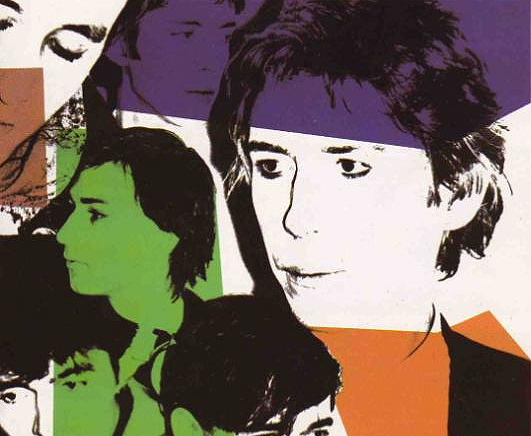

Strange as it may now seem, there was a time when The Psychedelic Furs seemed better placed than U2 to emerge from punk as the British Isles’ leading contemporary rock act. It didn’t quite work out like that, but they did enjoy headline success in the US and pretty much decamped there as a result. Of course, mention of them inevitably evokes memories of ‘Pretty In Pink’ and the Molly Ringwald/John Hughes film that took inspiration from the single. The album that housed it, Talk Talk Talk, remains for many (including me) the summit of the band’s achievements; an unholy, lurching, ramshackle glory, bedecked in Richard Butler’s burnished vocals and unrelenting cynicism. While Joy Division lamented unrequited love the Psychedelic Furs reduced it to its base functions, threw the patient on the slab and performed a series of clinical autopsies.

The Furs rose in tandem with punk – famously using a vacuum cleaner as additional instrumentation at a show at the Roxy after three Butlers [Richard, Tim and third brother Simon, who left the band early on] attended the Pistols’ famed stand at the 100 Club Punk Festival. Their self-titled debut, particularly with regard to ‘Sister Europe’ and ‘India’, was fleetingly engrossing. But as Richard will concede of his favourite Furs album, its successor was a more cohesive, definitive statement; wherein the ‘beautiful chaos’ they had foisted on the London gig circuit in the late 70s was marshalled and distilled…

Richard Butler: Punk was very influential. Coming out of how staid it had all been – you could love music, but there was no way of getting ‘there’ from where you were as a young man. Then it became – steal a guitar and write a song with three chords and people were up and doing it and the walls came down. We were like, ‘we can do that too, we don’t want all that old shit’.

Tim Butler: Seeing the Pistols at the 100 Club made us want to form a band. Other than that, there were very few bands that were any good. I would have to say the thing that made me want to play bass was John Burnel of the Stranglers. We used to see them play at the Nashville Rooms and he had such a great sound – and he didn’t stand around in the background! I wanted to be a drummer, but I couldn’t afford a drum kit. I wanted to be at the bottom end, bass or drums, so Richard said, buy yourself a bass, learn to play it and we’ll form a band. We always said that we liked the energy and drive of punk, but we appreciated the bands punks would put down, like Roxy Music and the Velvet Underground. We weren’t calling everything crap. I listen to more of the music from the early 70s than I do punk. I can sit down and listen to the whole of the first Roxy Music album. I can’t listen to the whole of Never Mind The Bollocks. It wears my eardrums out!

Beyond the Pistols, and to an extent the Banshees, the band immediately distanced themselves from punk.

RB: There were so many punk bands doing a very similar, faux-nihilistic take on things. We wanted to be ourselves. It was an undeniably huge influence. Punk rock, absolutely, enabled us to make music and get signed by record companies. They didn’t know what the hell was going on once punk rock came along.

At the time you were seen as direct competitors to U2 as band ‘most likely to’.

TB: That was probably because of the Steve Lillywhite thing. He produced Boy, then produced our first album. Then he said he wouldn’t do two albums by the same band. Then he ended up doing October, so we got him to do Talk Talk Talk. There was a little rivalry around 1980. We co-headlined some shows in Germany, Hamburg and Berlin.

You famously both appeared on that German TV show Rockpalast?

TB: Yeah – U2 did a great performance and went on to rule the world, and we were falling apart, did a bad performance and… didn’t go on to rule the world!

So how did the band’s sound evolve with Talk Talk Talk?

RB: The first album was certainly the sound of the band as it was at the time, and the second step was refining that sound. Steve brought out the massive wall of sound. It was a fairly large band, after all. He was well known for his huge drum sound. That worked perfectly with five other guys making an absolute racket over the top. Steve didn’t want to put his imprint all over us. He’d said our first record should be what a really good live gig sounded like. On the second record, we were free to do more overdubs and edits, because we had gone past a live gig in establishing our sound. We felt comfortable enough to make more of the production.

TB: On the first album he wanted an album that was going to be like a live concert, the vibe and energy. And pretty much the same thing with Talk Talk Talk – he was a very hands-off producer. He’d get the sound and leave us to arrange it. We did a couple of warm-up shows at the Marquee before we went into the studio. We had maybe a month or so in rehearsal studios, go there every day and start hanging out at the pub and leave there with a few cans and just jam round ideas. Invariably there were some fights happening. These minor fights, that energy – Talk Talk Talk is my second favourite Furs album, but it’s the first favourite for just about everyone else in the band. We’re all really proud of it.

The songs were pretty much prepared before the studio sessions, weren’t they?

RB: Yeah, but I’m really lazy with lyrics. The lyrics were probably half-written. Then we came up with ideas. I remember having charts on the walls of what had to be recorded for each song. I would invariably try to leave the vocals to last, because I was writing. At the end of a day Steve would say, ‘Oh, we’re doing ‘Pretty In Pink’ tomorrow.’ So I’d have to go away and make sure I had all the lyrics together.

So the music would inspire the lyrics?

RB: There would be a vocal melody on it. That would have been a bit too much to write in an evening! There was usually a vocal melody and skeleton lyric I would have to finalise.

Does the pressure to finalise actually produce better results?

RB: Yeah, I’ve always been a really bad procrastinator in everything, and pressure of that kind works to my benefit.

TB: Richard always used to be writing stuff down on pieces of paper – whether he was in a bar or a dressing room or sitting at home. He’d suddenly pick up a piece of paper and write something down. He’d have notebooks with bits of napkins in it, etc. Sometimes he’d just be hit by a lyric. We’d just be jamming along at maximum volume, and he’d be sat listening and if he liked an idea, he would say hold on, that’s cool, now we need it to go somewhere else – a chorus or a middle eight. Sometimes we would go into rehearsals in the morning and come out with pretty much a finished idea, like ‘Into You Like A Train’ – that was jammed and the rough idea for the lyric came out of that.

Did you ever comment on the lyrics? Or was Richard very much the custodian?

TB: He is so hyper critical of himself, even of a finished thing in the studio. He was such a great lyricist – I’m not saying that just cos he’s my brother! He didn’t need any comments on where he was going lyric-wise. And in the same way he would trust us. He wouldn’t turn round to [guitarists] John [Ashton] or Roger [Morris] and say, play this or that. It just came out naturally, whatever sounded good to us. You get bands that have ten unreleased songs from a certain period – we didn’t do that. We were very, very self-critical. We would never take anything right the way through to the recording stage and reject it. We would always go in with just enough songs, and maybe one extra for a b-side.

The early Psychedelic Furs were famously a quite quarrelsome entity.

TB: The arguments would last five or ten minutes, then it would be smooth sailing. If there weren’t arguments about the music we felt that people didn’t care enough about it. And it would come out as a lesser piece of music. If you’d just had an argument with someone, when you came to record in the studio, you have something to prove – you play with passion, you play harder. Maybe that’s why the album has that energy and a certain amount of aggression. I think those things are healthy in recording. You can rest on your laurels if you’re on take number forty – there’s nothing better than a fight to get you up for a new take!

Talk Talk Talk was slated at the time by critics. There were objections to sexism in the lyrics – specifically the robust carnal longings of ‘Into You Like A Train’, and lines like ‘I don’t want to give you flowers, I just wanna sleep with you’. It always seemed to me that you dealt with sex and romance in a very functional way.

RB: That was a little surprising. I didn’t find there were any attitudes on there written as a male that couldn’t also be felt as a female. If I were to posit the idea that I didn’t want to have a romance with somebody, I just wanted to sleep with them, I was accused of sexism? I think that’s a fairly commonplace way of thinking for males and females. Not every time a girl has sex does she want to get married and have babies with the person – you know? It seemed a curiously old-fashioned way of looking at it all, and in a way, reverse sexism.

I liked the brutality and the nihilism about romance throughout the record. It’s exceedingly blunt.

RB: The idea of romance is a weird, ephemeral idea that’s put forward by advertising and religion, I suppose. How realistic it actually is? I wonder.

Why were you so bleak?

RB: I don’t know. My father was very blunt about stuff like that. He was a Communist/atheist, a very blunt-spoken Yorkshireman. I probably got a lot from him. I got a lot of the cynicism, I suppose, from Bob Dylan when I was growing up, and the energy of punk rock was very much part of that as well.

Brings to mind John Lydon’s quote about sex being three minutes of disgusting squelching noises.

RB: [Laughs] Only three minutes, Johnny! You’re not trying!

Talk Talk Talk‘s keynote single was ‘Pretty In Pink’; a swirling, exhilarating tale of peer pressure, backbiting and sexual vulnerability. John Hughes’ hugely successful film took the title – less than literally – as its starting point.

TB: It was a popular song before the movie, and I think it is a classic song. We re-recorded it for the film because they said there was some slightly out of tune guitar work on the original. I could never figure it out, but that was the reasoning. Maybe the original sounded too ‘dense’ for a soundtrack. We went to the premiere and we met John Cryer [aka Duckie in the film] who seemed like a nice guy. He said he was a fan from the original. Molly Ringwald liked the song and apparently asked John Hughes to write the movie around that song. Now, the movie has nothing to do with the lyrics to that song.

RB: No. The idea of the song was, ‘Pretty In Pink’ as a metaphor for being naked. The song, to me, was actually about a girl who sleeps around a lot and thinks that she’s wanted and in demand and clever and beautiful, but people are talking about her behind her back. That was the idea of the song. And John Hughes, bless his late heart, took it completely literally and completely overrode the metaphor altogether! I still like the song.

It’s not become an albatross?

RB: [Laughs] I don’t know if it has or not! Maybe some people go, oh, that’s the band that did ‘Pretty In Pink’. But if they didn’t say that, maybe they wouldn’t have anything to say about us!

And what about the bands that profess their admiration for the Psychedelic Furs? Does Richard hear echoes of Talk Talk Talk in the likes of Interpol, etc?

RB: Bands like the Killers come forward and say they were very influenced by us. Often bands will say it and I don’t personally hear it. I’ll listen to them and go, nah, they sound more like Joy Division!

Psychedelic Furs play the Cheese & Grain in Frome (24 October), Manchester Ritz (26th), Birmingham Institute (27th), HMV Forum London (28th) and Glasgow 02 ABC (29th).