It’s an interesting coincidence, but the non-more-North-American sport that is baseball has more in common than you might think with the Guatemalan creation myth, Popol Vuh. In that tale, the Mayan hero twins avenge the grisly death of their father, playing a primitive version of the sport against the dark lords of the underworld and emerging victorious for the first harvest and the beginning of time. That’s the beginning of the better known part of the story – the start of The Long Count, the Mayan calendar which supposedly sees no future past December 21, 2012, heralding the moment that the ground opens up and swallows us deep into its fiery, apocalyptic belly.

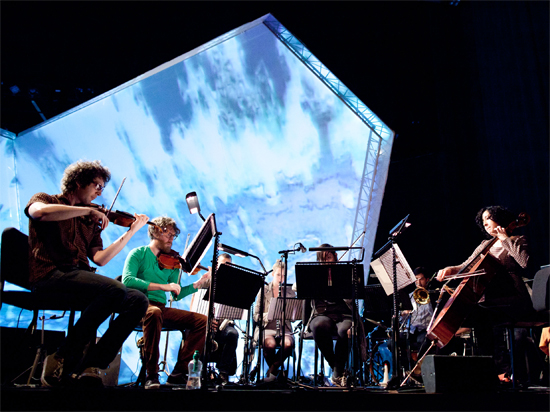

At London’s Barbican on February 2, 3 and 4, The National’s twin brothers Aaron and Bryce Dessner will perform in the UK premiere of their multimedia song-cycle entitled The Long Count, along with a 12-piece orchestra, video and staging installations, and singers Shara Worden (My Brightest Diamond), Tunde Adebimpe (TV On The Radio) and Kelley Deal (The Breeders). Originally written and performed with Kelley and Kim Deal in 2009 at the Brooklyn Academy Of Music’s Next Wave festival, and later at Eindhoven’s Muziekgebouw, the orchestral and visual piece explores not the death and destruction aspect of the myth, but the "time before time; the indivisible moment before creation is expressed". While the project’s visual artist Matthew Ritchie suggested taking the story as the conceit of their collaboration, the Dessner twins discovered greater personal parallels within its narrative.

It barely requires pointing out that baseball is full of easy, enduring metaphors for life – if it was good enough for the Mayans, there’s no reason that the author of hit novel The Art Of Fielding Chad Harbach and the Dessner brothers shouldn’t continue to play around with its fruitful symbolism, especially when both find ways to cast the culture around it anew. Although both The Art Of Fielding and The Long Count are the results of careful study, their respective explorations of innocence and formative male relationships are beguilingly executed. For the Dessners, coming from The National, whose singer and lyricist Matt Berninger’s calling card is trading in big American archetypes – presidents, cheerleaders, white collar workers – tying the sport to their nation’s creation myth is an intriguing way of marking out their own corner of that band’s growing mythology. The Quietus spoke to Aaron Dessner about The Long Count just before Christmas, as he played around with piano sketches on a dark afternoon in Copenhagen.

I’ve not seen the performance yet and there aren’t many clips of it on YouTube. From what I’ve seen, it strikes me as a fairly solemn piece. Is that a fair judgment? What new colours are you bringing to it?

AD: It ranges from gothic, almost… we laugh about it, but there’s almost a metal quality to some of the music, a few little moments, but in an orchestral way! It gets quite loud, but then there are really beautiful, playful moments. It’s about our relationship as brothers, so some of the quiet moments are mirroring going on in the guitar playing and the rest of the music, and those moments might seem beautiful or solemn or something. I think the way we plan to expand it is to bring in some more orchestral writing. Not linear, but more defined melodic material in a few places. Also I think there’ll be at least new song in there – it’s really a song cycle, there’s nine or ten songs in it, and we’ll at least have one new one that Shara Worden will sing, and probably another one that someone else will sing, but I can’t tell you who that is yet! It’s a new character, who’s very exciting. [It’s Tunde Adebimpe from TV On The Radio.]

It’s easy to assume that The Long Count is about the apocalypse, particularly with that supposedly due this year, but you’ve said before that it isn’t. Why did you avoid that aspect of the story?

AD: That’s definitely there. This apocalyptic tone is there in the performance and imagery, but we’re telling the story of creation, not the end of the world, in a way. I can’t remember exactly why we chose to do it that way! It ends in a hopeful way. And it’s funny, there’s so much you read about, so much out there about this idea that the world’s gonna end, and it’s not really the reason we wanted to work with this myth, or the message of this performance. It actually ends with a song called ‘The Long Count’. It’s a song we wrote with Kim Deal but Kelley Deal actually sings in it, and for me it has the most hopeful tone of the whole performance, it ends in this very beautiful place.

Can you take me through the rough song cycle? I know about the concepts it’s based around, but it’s hard to get a grasp on how you explore the baseball, Mayan and brotherly elements of it without seeing it.

AD: It’s very abstracted from any kind of cohesive narrative. The Mayan creation myth, Popul Vuh, involves these hero twin brothers who go to the underworld to find the missing head of their father, who has died and is in the underworld. They’re going through this series of tests and challenges, and it’s a very non-linear story, it’s episodic. Matthew Ritchie took a lot of that text, and there are multiple sets of twins in that story – there’s the twins, then their father and uncle are twins, and that was the original reason we involved Kim and Kelley Deal, it was this story of twins. Matthew took parts of the text and developed his own [visual] language which then informed a lot of the lyrics. The songs are loosely based on characters and stories within that text, but not from point A to point B in that sense.

Matthew’s work, a lot of it deals with genealogies and mythologies of creation, and the story of the American creation myth, which is Popul Vuh, is all these stories of birth and destruction, and it ends with the harvest and the twins return to our world and put the head on a stick and that becomes the harvest. In a way, our story kind of begins – the end of it is the beginning of time, essentially. We’re working backwards or something. And the film is meant to express this sort of… in a visual way, these ideas of birth, rebirth and destruction. But it’s all very abstract, so what you see is a number of characters from the myth appear in this same song, and at times you get literal information from that – there is actually a song called ‘Tests’, and it expresses that idea of these two brothers and the tests they encounter on their journey.

The baseball is a loose framing of our stories. Bryce and I were born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1976 at the height of the Cincinnati Reds dynasty. We had these legendary, almost mythological players like Pete Rose and Johnny Bench and Joe Morgan and Joe Foster, and all these guys that are in the baseball Hall of Fame, and they all had great nicknames. We grew up totally idolizing them and collecting baseball cards, that was our first real collaboration. We would store them perfectly and make long lists of all the cards that we had. That was our first way of organizing and collaborating, and definitely at some point we went straight from that into music, when we actually took our baseball card collection and pawned it to buy guitars. My dad came home from work one day and was very upset, we had traded them in at a pawn shop for a small fraction of their value, before baseball went to hell. This was in the 1980s when baseball cards were worth a lot of money.

The connection is that in the Mayan myth, the two brothers play the ball game, which is kind of a pre-cursor of modern ball games, and we actually play ball games – in the original version of The Long Count there were two twins on stage playing handball. And at least in Holland, we actually played baseball but with a guitar in the beginning of the piece. We use the actual broadcast of the Cincinnati Reds beating the New York Yankees in the 1976 World Series, we use it in this abstracted, experimental way, it’s used as samples in places, just connecting that idea of our own personal mythology with baseball to this great classic creation myth of the Mayans. It’s very abstract, is what I’m trying to tell you! It’s not like an opera where there’s a libretto to follow, it’s more this abstract song cycle.

Was the baseball 1976 thing a big cultural hangover for you and Bryce? How did you get into baseball?

AD: My dad got us into baseball. Ohio is in Middle America – all the things you imagine about baseball and homecoming and football games and apple pie, that was our life. We played all the American sports, and when we gave up playing football because I got my ribs broken playing American football, that was a huge disappointment. All of a sudden we were sissies playing American soccer!

Did you both stop playing at the same time?

AD: Bryce never liked football but we played it. In Ohio, baseball, basketball and football – if you play those you’re a jock. That’s evolved since then, but basically baseball was something we grew up with from the very beginning. We would rush home from school and turn on the TV when Pete Rose was on – he’s this infamous player who holds the all time record for hits in baseball, but he was disqualified for betting on games when he was the manager of the Cincinnati Reds later. He was actually a player manager and it was the end of his career, but he was really the hero of the Big Red Machine.

We grew up in the shadow of that dynasty, and no Cincinnati team, whether baseball or football, has ever come close to that kind of storied dynasty of the mid 1970s. Bryce and I shared a room – still when we go home, we share a room – and the beds are side by side and there’s this huge picture of Pete Rose diving headfirst into home base. It’s a signed picture my dad got us when we were little boys. It’s still there, and it’s very much part of our existence.

One video sounded like Colin Stetson was playing with you. Is he in it?

AD: Colin was a part of it the first two times, he won’t be in London but there’ll be someone else filling that role. He’s been a part of it for sure. Some of it was inspired by his playing. There are some interstitial moments where his way of cycle breathing and playing is featured, so we hope that even though he won’t be there, it will be a part of it.

Taking it back to its conception – before Joe Melillo [BAM’s Executive Producer] asked you to do it for BAM, where did the idea come from?

AD: We had started collaborating with Matthew Ritchie a year or two before Joe approached us, and especially Bryce had been working more in that context, doing collaborations with visual artists. Bryce and I actually performed some experimental guitar thing at Matthew Ritchie’s opening at the White Cube Gallery in London in 2008, or maybe 2007, and that was a collaboration with David Sheppard who’s a sound designer from London who does a lot of spatialising of sound, where he would sample us and fly it around different speakers. He’s a total wizard with being able to take something we’re doing live and manipulating it. He’s also part of The Long Count. So I think it came out of that, it was so much fun, the experience, setting up in the gallery. David placed speakers everywhere, he was flying the sound around, manipulating and changing it. It was disorienting, but amazing – and with Matthew’s imagery there was a powerful alchemy that was happening. We had that idea that we should develop it. When the opportunity arose, we just ran with it.

I understand that Matthew brought the Popul Vuh element to the piece. Did you and Bryce have to study to get up to speed with it, or was it something already of interest to you?

AD: I think we both were familiar with it, we knew what it was. When it became the subject of this collaboration we had to read up and get lost in it a little bit, but Matthew – he’s a really amazing thinker. He’s able to very complex ideas and stories into terms that you can understand, and that are relatable. A lot of his work, whether films or paintings or sculptures, there’s almost always some kind of concept there, whether you can see it or not, of these mythologies and creation. There’s always a conceptual background to something he’s doing. We had gotten used to that in his work, so it was a natural feeling to have it be a part of what we were collaborating from.

I was watching a video interview with him about The Long Count which was interesting – he said that for him, it also extended to ideas of games and combat, conflict and play in every day life. Was that of significance to you too?

AD: Yeah, definitely. I remember… early on, it was very much about games and play and tests, and we tried to affect that in the music. A lot of the music involves these chases, or mirroring – my brother and I can play guitar in really unique ways together because of how we grew up. Literally I can look at his hand and play the exact same thing or the exact opposite thing, or a key off. What usually happens is that I’m playing something and he plays a mirror or echo of it, and a lot of music is like that, and it’s extended into the ensemble also, so it’s like twins also. That extends into the film as well – you see the film, the two diamond shape films, and then they reflect down off of this mirror floor, so everything is doubled or quadrupled, so this has this interesting effect where it’s all very playful.

You must both be acutely aware of the ways in which you and Bryce work together and apart.

AD: I think we have this instinctive feeling that if we hit a wall at some point, that the other will be able to break through it. We have different tendencies: he’s much more academic about music than I am, and I’m more visceral or spontaneous. It’s probably easier for me to generate lots of new ideas, a constant stream, and in a way it’s easier for him to finish those ideas, and maybe elevate them beyond a simple idea. But then he’ll do some work and I’ll take it further. There are very few times where either of us is working on something where the either isn’t in some way part of it. Bryce is writing more orchestral work now, and some of that I’m not involved in it, some of that I am, and in some ways that’s a different exercise when you’re writing in a more traditional way, as opposed to collaborating. We’re always finishing each other’s ideas, and it works really well in The National, and in some ways it works even better in these more expansive, experimental ways. There aren’t these restraints. With The Long Count, there are a lot more musicians to bounce things out of and draw on, different voices and things. It’s liberating.

I know how fraught The National’s writing process can be – the two of you must enjoy having more control here.

AD: The songs were written with Kim and Kelley Deal and Shara Worden, so there was an element of that difficulty, of having to find a middle ground that works for everyone and work with those people, and I think we’re born to collaborate, we’ve always been like that. It’s easy for us to do a lot of work. A lot of our friends think we’re workaholics or that we’re kinda crazy because we’re always doing these different projects, but it’s just because there’s two of us – it makes it so that it’s a lot easier to get a lot done. You’re not struggling alone by yourself, there’s someone else to come in and vet it, to make it easier. The song that Matt originally sang at BAM, ‘Tests’ – Matthew [Ritchie] actually wrote the lyrics – but Bryce and I wrote the melody and put it together, Matt changed a few little things, but basically it was written completely for him. It was a cool experience and for him too. It was compelling. It wouldn’t be a National song, but everyone enjoyed it and he loved singing it.

He’s playing the underworld lord there, is that right?

AD: He’s the lord of death or of the underworld, yeah. An apocalyptic figure!

Isn’t that based on some old nickname he had, you used to call him The Dark Lord or something?

AD: Yeah, at various points he’s had a tendency to be quite a negative person, at least on tour. That’s actually changed a lot in the last two years, and now he’s hilarious and almost sunny, positive. I think we’re all just a lot happier now.