All photographs courtesy The Long Blondes

How do you remap your past? I am talking to my laptop screen, to moving images of Kate Jackson and Dorian Cox of Sheffield indie pop band The Long Blondes about just that. I presume the images are the real Kate and Dorian, old friends. It seems so at any rate; they still spar with me in the same way. We pick over what we can remember of times shared in the bars and backstages of Western Europe; holding a digital mirror to Tony Wilson’s quip, “print the legend”.

Cox, guitarist and co-songwriter with Jackson, and a man who can truthfully say he knows what it’s like to be dead, has just told me “pop music is meant to be disposable”. And yet here we are, after all these years, discussing the deluxe re-release on Rough Trade of their sparkling debut, Someone To Drive You Home.

The need to embody nostalgia is very strong in the music industry, where back catalogues have to be constantly revisited to make cash for unasked questions. You could never imagine some idiot orc in publishing giving Dan Brown’s legacy a dust down for a Da Vinci Code 20th Anniversary Tour. Yet one can’t really square such industry cynicism with The Long Blondes.

Feisty, funny, talkative and supremely confident in what they achieved, the Sheffield quintet’s work deftly avoided the dreary “Charles Atlas” legacy of British pop music’s post-Libertines explosion. How did this disparate bunch of provincial arty refuseniks – in Cox’s own words, “Sheffield’s most obnoxious band” – none of whom could play a note beforehand, make something so intriguing and fresh out of everyday subject matter?

The Things That Dreams Are Made Of

Someone To Drive You Home is one of those records that managed to make the story of a place or situation appear both intensely personal and resoundingly international. Like the gloriously dumb but life-affirming misappropriations of Bridget Riley’s work as OpArt record covers, the Blondes somehow warped their bedsit visions of the pleasure principle into a wider feeling of transnational fun.

Someone To Drive You Home is a true pop misappropriation of the title of William Morris’s earnest artisan-socialist book, News From Nowhere: a bulletin board for the lonesome groover. A listener could quickly connect to the record’s lyrics or the manner of their delivery, the atmospheric licks and seedy synths and the simple, steel-beating rhythms. Many bought the same knock-off clothes from Help The Aged or Guide Dogs. Others could just about afford the flimsy guitars and patched up synths the band used.

Kate Jackson says: “The album and the narrative of the songs drew people to us. They were modern takes on those classic kitchen sink dramas. Girls could relate to the songs, and buy the beret I had from the charity shop because that’s where I bought it! I looked like any of them because I wasn’t wearing anything designer. It was easy to look like us. And of course then they could go and buy a second hand guitar and start playing. That was the point for me. Then there was the other side, where we liked pop stars being all aloof and special. Why not do both?”

Chainstore glam-punks who couldn’t stay in tune, the band also indulged in the twin British loves of dressing up and going out on the razzle. Dorian Cox says: “We took ourselves both incredibly seriously and not seriously whatsoever. I took writing the songs and what the band represented incredibly seriously. But I wanted to drink some fizzy pop and have a laugh as well.”

The band’s appetite for living was there for everyone to see. Kate Jackson adds: “We were on an adventure, we wanted to see lots of things we’d never seen before, and we were appreciative of the fact that we were able to immerse ourselves in other cultures by being in a band, because none of us would have been able to afford travelling around Europe. It felt like we were on one of those old fashioned Grand Tours… The interesting thing about being in Europe is similar to the interesting thing about being in the UK, which is going into bars and pubs and meeting the people who live there. And having conversations over a few drinks.”

The Long Blondes were a true road band, in love with gossip and chance meetings. Drummer Screech Louder recently told me that one of his favourite band memories is of sitting in an Amsterdam cafe and watching a cavalcade of aged and beehived bartenders, dogs, market workers and drunks all singing Dutch chanson one Saturday afternoon. Unremarkable, only this particular afternoon became a full-blown pre-gig party before a prestigious showcase at the legendary Paradiso club. Real life, however surreal, mattered more than industry plaudits.

Dorian Cox remembers the time: “I think we were all really keen on meeting new people everywhere we went. I’m really pleased to have had that opportunity. The nice thing is I feel I’ve got friends all over the world now. I couldn’t believe reading about bands like Oasis going to Japan and staying in their hotel. I wanted to take as much out of the world as possible. Even though we did have very British reference points, I do think we were a transglobal band.”

Unlike Morris’s carefully garlanded ideas of pastoral socialism, the band didn’t take much to ideas of nurturing the craft of the profession, initially at least. Cox says: “The first time we went to New York we didn’t have hard cases, the guitars were in soft gig bag cases. I remember sitting on the plane and seeing the airport worker throwing suitcases on top of our guitars. And these were guitars we got from charity shops and I remember thinking, that’s not gonna last the journey!”

Jackson adds: “We never stayed in tune anyway. It didn’t really matter to us.”

Cox: “Exactly. That didn’t matter. I honestly feel we were genuine punks, and in a genuine way, too. Not just doing a ‘1977’ kind of thing, but the spirit was there with us. And it came from post punk bands like Swell Maps who were a reference for us. People did get that. But I always found it strange when people would slag us off for being out of tune. I never said I wanted to be Keith Richards, I wanted to be Edwyn Collins. I have never once listened to a band and thought, ‘Ooh lovely how fantastic, they’re all really in tune.’"

The “art” of The Long Blondes was combustible, quick-fire and simpatico. If not a craft, per se, this art gradually became embodied as a way of living, playing and writing. The band knew the value of making fast, bold sketches and instantly using them. Quick work gave them confidence and sometimes opened creative doors that fiddling around in the studio couldn’t. Dorian Cox admits he was “never interested” in the process of making records, preferring to get things down quickly and move on. “Yes, most were done in one take but that’s fine. I was brought up listening to Northern Soul. And every Northern Soul track is a one take demo. Similar with many Motown songs. It’s pop music and it’s meant to be disposable. Get it out there. If it’s got energy and it sounds interesting that is the most you can ask for from something.”

Remake / Remodel

It is true of many debuts but the band’s formation is a crucial element of the effervescent spirit of Someone To Drive You Home: a record that reflects the impatient, motivated personalities that made it. Some elements about remapping any past take on a mythical aspect. To misquote an old Russian proverb, there is no liar like an eye witness. Sometimes these remnants of memory seem charmingly human and uncontrollable, especially in this current age of instant answers and algorithms. But both Kate and Dorian are adamant the formation of the band is as haphazardly quotidian and as legendary as they tell it.

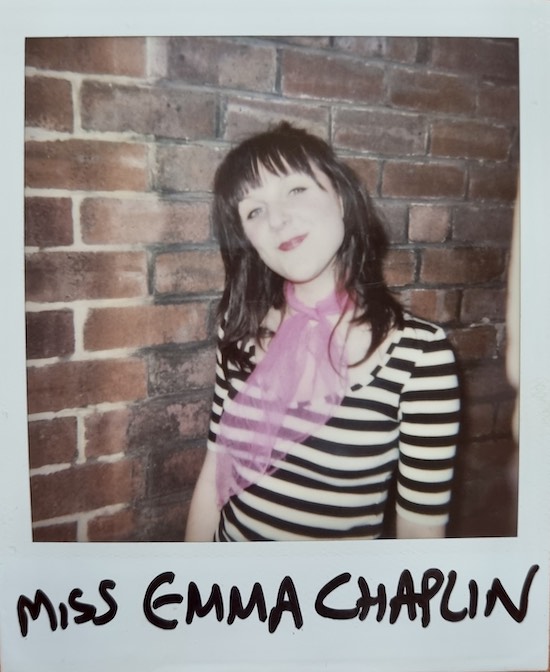

Cox says: “Lots of people think I’m lying but really, everything we say happened, happened. We formed a band because to begin with Reenie [Hollis] bought a bass guitar. We were living in the same house at the time. I thought, that’s amazing. And the next day I went and bought a second hand guitar and thought, let’s just do this. I was just so driven, I knew we could do it. I wrote a couple of very simple songs and off we went.” Kate Jackson concurs. “I remember Dorian ringing me up after we’d just met at a gig and saying, ‘You look like you can sing, let’s form a band.’" Back to Dorian: “I was standing in the Barfly in Sheffield watching Ikara Colt. And I turned to Emma [Chaplin] and said, ‘We can do this.’ In fact the only four people there were me, Emma, Kate and someone else. That is exactly how it was.”

Sheffield was an outsider city then, where people got on with making their own entertainment, such as forming bands. Kate Jackson remembers Sheffield boasting some “genuinely arty and interesting people”. Salter Lane Art School (where Jackson studied) boasted Nick Collier’s Pink Grease, “the Roxy Music of Sheffield”, who were busy provoking the locals, courtesy of a sonic assault that incorporated homemade synths, glam-punk attitudes and a ton of makeup. Jackson says: “They were incredibly eccentric onstage and didn’t sound like anybody else. Another band was Hiem, who had glam rock elements, again a very Sheffield thing, where the electronic music had an element of glam to it.”

The record’s core attitude was nurtured by other, more everyday elements. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to see The Long Blondes’ rise mapped onto the city that formed them. Like another working city, Rotterdam, Sheffield is a permanent building site that is knocking down walls on its way to the future. After the interview Cox and Jackson both mailed me with their thoughts on how the city initially shaped the space for Someone To Drive You Home. Again we are trusting to the memories of others. Poor fodder for the historian. But Cox and Jackson’s brief flashes of remembrance (here deliberately mixed into each other for effect) feel evocative and ultimately trustworthy.

The reader must imagine the following: “long, long walks in the rain up and down Abbeydale Road to practice in the old steel factories in Stag Works on John Street: prime territory for finding unwanted musical instruments, brogues and Tretchikoff prints. A few pints in the pre-gentrified Broadfield opposite the old Snooker Hall at the Abbeydale Picture House. Or a couple of hours’ sleep, before walking up Empire Road to work: the library at Sheffield Uni. [Dorian was ‘The Mod In The Library’, Sheffield Ed] That library was also reminiscent of the library scenes in Wings Of Desire. The Paternoster lift in the Arts Tower, too. Perhaps a walk into town via the underpasses, walks that were straight out of Threads, past the monolithic concrete substation at the bottom of the Moor. Then there was living in a flat above a sex shop called DV8 on Infirmary Road, or drifting off to sleep to sound of the Supertram rolling by. What about the concrete labyrinth of the old Park Hill Estate which, pre-gentrification, was still very dodgy but a great backdrop for photos, as was the old Roxy Disco before it became the 02. And we can’t forget The Rutland Arms with its global treasures. Perhaps the centre of it all, nestled within 7 hills and a spider web of glistening street lights.”

A strange but beautiful old pub, with its eccentric landlord and huge ceramic statues of pharaohs and Egyptian gods staring at you as you went to the jakes, The Rutland Arms was HQ for the band, and a nerve net for their friends. Snugly placed in a set of half-demolished streets, impenetrable works buildings and concrete phalanxes of futuristic estates, the pub’s very incongruity fitted into the wider cityscape.

Dorian Cox sees the band’s early songs as “almost skeletal in the way that Sheffield is a skeletal place. Almost something not quite working, or not quite right. Which is why I personally think the debut record has stood the test of time. I can listen back to all them songs and they don’t feel like traditional pop or indie songs. That is still very interesting to me.” Kate Jackson admits that it took her a long time to listen back, as her hankering after a perfect sound led her to think in a different way about the early days of the band. Now, Jackson sees the recordings in the Stag Works with local producer Alan Smythe, as “really capturing the essence of what we were. Full of ideas, and even if we couldn’t play in time, we knew what we were doing. Contradictory but interesting.”

Cox brings up "art, books and music" shop Rare And Racy: “What a crazy place that was. Some of my fondest memories looking back are in Rare And Racy. People often think of a place as reflected through the famous people from there. So people probably thought back then that Sheffield was full of, like, Arctic Monkeys-type bands. But we’d go in there on a Sunday at ten in the morning with hangovers and the bloke would be blasting out Melt Banana at 11 on the dial and we’d be thinking, what the fuck is this? Sheffield is one of the strangest places in the UK if you ask me.”

Did the strangeness and attitude bleed into the final record? Cox thinks so. “I think you can still hear the weirdness in the grooves of that record. That shop was a perfect example of Sheffield’s underbelly back then. And that scenario is the perfect example of both the spirit of Sheffield and The Long Blondes: going into a record and a book shop at 10 am and hearing Melt Banana. There was something about the obnoxiousness of that behaviour that I really liked. And from day one, The Long Blondes were a truly obnoxious band. I certainly wasn’t there to placate the many failed musicians in Sheffield. We would be sharing rehearsal rooms with certain bands. Back then, we’d go to the pub and they’d be laughing at us a bit because we couldn’t play properly, yet they’d still be in the same rehearsal room a year later playing the same sub Pavement riff…”

Kate Jackson: “While we had been around the world.”

Do You… Work Hard?

Sheffield has a famous work ethic; one that may not be immediately associated with a bunch of beret and cravat wearing librarians and art students. But the eighteen month run up to their signing to Rough Trade and the release of Someone… saw the band produce a phenomenal amount of material, especially if one considers that bands which rely primarily on writing good pop songs can’t afford to cut themselves any slack with seven minute instrumentals. Dorian Cox mentions a driven band recording four songs on their fourth ever practice, “there and then”. Kate Jackson chips in to remind Cox that after the band’s third gig, they agreed to local indie label Sheffield Phonographic Corporation releasing a single [‘New Idols’ bw ‘Long Blonde’] and sorting out some gigs in Europe.

Jackson remembers: “It was easy back then, none of this Brexit bullshit. We got invited to play in Dresden so we just went. We stayed on someone’s settee. Easy.” Both Cox and Jackson talk of the plethora of songs that flitted through a constantly revolving live set: ones that could have ended up on the debut, only to be replaced by another new batch, with “a hell of a lot of songs getting ditched” along the way. Kate Jackson recalls fleshing out and recording ‘Once And Never Again’ and ‘Giddy Stratospheres’, “in the same practice session on a dark January night: unbelievable now but then it seemed so quick, so easy”. Again, a beautiful moment that sounds to have more in common with Robert Graves’s The Greek Myths, but Cox claims that as soon as he gave Jackson a notebook of his lyrics, the songs would “fly out”.

The band’s determination saw them wait for the label they wanted; Rough Trade. Both Jackson and Cox feel they were right to wait, as this engendered a feeling of specialness during a “strange and interesting period of being a band that wasn’t signed but being a band that was on everyone’s lips”. Both are aware that they could have recorded the wrong songs in the wrong spirit, and disappeared into the murk of what was an increasingly saturated market of British alternative pop bands. When it finally appeared the record came as a mild surprise for a fanbase who knew a set of songs such as ‘Autonomy Boy’, ‘Appropriation’, ‘Peterborough Poly’ and ‘Darts’, or recognised ‘Lust In The Movies’ as two separate songs (‘In The Movies’ and ‘Lust Etcetera’). Added to this were new and glorious b-sides such as ‘Five Ways To End It’ and ‘Fullwood Babylon’. Kate Jackson: “We were just very prolific back then.”

This may sound like what a working band should do, but it is worth remembering, specifically if one was “looking in” from the other end of the North Sea, that an awful lot of thin gruel was being passed off as fine stew back then. Virtually every weekend British and American bands would appear on the European circuit and play their three good songs and then be shunted off to another venue. Signs of a sickening industry desperately trying to cash in. A human production line in which some may not have realised they were actually in a band. Cox and Jackson also remember the long line of “trainer bands.”

Dorian Cox: “We’ve gone on tour by accident.”

Kate Jackson: “We’ve formed a band by mistake.”

Dorian Cox sees the reason that they escaped the drear fate of many of their short lived, over hyped contemporaries was that “every song had to be good. We had a certain look, of course, which is what bands should do. But I think our collective songwriting and creation as a group was so strong, if I brought a new song to practice it had to be at least as good as the songs we had, otherwise it was pointless. We were so determined.”

Other obvious elements that set The Long Blondes apart were the things they liked. A literary and film-loving band, they brazenly used their influences to further enrich their appeal. No songs about trainers and football here. Reading matter during recording sessions included Peter Cook’s Sadly I Was An Only Twin and The Kenneth Williams Diaries, amongst other things. Someone to Drive You Home is a record that openly references Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s film Bedazzled, Scott Walker, Faye Dunaway as Bonnie and even, in ‘Heaven Help The New Girl’, a reference to their own song, ‘Once And Never Again’, reminiscent of how the John Lennon talks of Paul McCartney being the Walrus in ‘Glass Onion’.

The record also revealed a strong love of glam rock and the seventies, from the cover to the simple tom-tom beat. Importantly this was a tight record; romantic, glamorous and often funny, showing a clear reason for every song being there. An approach to pop music that often aped their musical heroes, Bowie and Suede, who played with the same “fractured surreal elements to Britishness” and who made records “full of romance and escapism”. Cox explains: “We never liked that jingle-jangle version of Britishness, the story of going to a chip shop and kissing a girl. We were more sexy. There was a lot more sex involved. But an English version of sex and seediness. Newspaper on the toilet seats.”

It could be argued that by the time the record was released, The Long Blondes resembled a pop music version of one of those interwar kits for intelligent boys: the box lid showing how to make a bomb out of lead parts on the living room floor, whilst father smokes his pipe. A heady concoction and one that caught the imagination of those enamoured of bands like Sea Power; a wider demographic of lonesome, arty, socially unsure people who lived through the records and books they owned. Everything was set for the music industry to do its worst.

A Giddy Stratosphere

Suddenly, everything felt like a blur, where the travelling stuck in the mind more than the creative process. Dorian Cox remembers “a whirlwind almost punctured by wonderful moments when we met people who we could go to the pub with in a different city”. Kate Jackson laughs at the cliche but still claims no-one in the band fully realised that signing the contract meant a relentless cycle of recording, touring and writing. “We’d written the first album so we went straight into the studio and then we went immediately on tour. We didn’t really have any time back together in Sheffield and we didn’t feel we had a lot of time to write the second album [Couples]. I think we had three weeks in total. And I was caught up in travelling and doing gigs and interviews.”

Not being able to just go to the practise room in Sheffield meant things didn’t feel quite the same. But Dorian Cox thinks the pressure helped the band concentrate and find another way to apply their ingrained work ethic. “When you are caught up in the industry side of it, concentrating on the job in hand when we were back in Sheffield was important. I would take certain chemicals to help me stay up all night to write songs, because I knew we had two days at home. And I would write a song in those two days before we had to go back to Slovenia or wherever. In a way I enjoyed it. It helped me streamline everything. We couldn’t luxuriate in moping around in rehearsals. It was more about the fact that we had a new set of songs, so get in there. We were really focussed on the songs on Couples, and I would say they were as ‘done’ as the songs on the first album. The business side of it when I look back… it was wonderful but you have to be a certain kind of person to deal with it. A lot of my mates would say, ‘Oh you just dick around and get flown to America.’ It’s not as if I’m on holiday: it is hard on the body and the mind. But I wouldn’t change any of it for the world. I feel The Long Blondes conceived something from scratch that stands the test of time. If that’s on my gravestone then I’m happy.”

In June of 2009 Dorian Cox suffered an untimely and shocking stroke effectively ending the band. At the same time it felt there was a shift underway in independent music, with more “considered” attitudes shaping tastes. A move away from quixotic, if often gullible bands financed by an increasingly hidebound industry towards the supposed blue skies of the individual: the musician-marketer-label-boss-producer stuck in a new straitjacket of digital market economics. Would the band have been comfortable in that new more serious and individual world?

Kate Jackson: “I was definitely in it for the long haul. I thought, ‘I am a pop star, take it or leave it!’”

Dorian Cox: “Maybe we stepped through the portal and turned the light off. We were maybe the last band to benefit from the industry and also work in the way we did. But it’s important to know, even though from the outside The Long Blondes may have looked like a world that was put together, it wasn’t. It was much more to do with the fact that our reference points matched. I can remember the first time I spoke to Kate and we talked about music and we shared the same taste in bands. The Ronettes, The Fall and Guns n’Roses. And I wiped the last one off the list because I fucking hate Guns ’N Roses, but the first two were strong enough for me to go ‘yes, let’s form a band.’”

Someone To Drive You Home is reissued by Rough Trade on December 10