Bobby Krlic’s debut album as The Haxan Cloak, which emerged earlier this year through Aurora Borealis, was far more intricate, carefully arranged and accomplished than your average debut. The Haxan Cloak was a set of eight dense, light-starved compositions that, as the project’s name suggested, alluded to very British ideas of the occult. Its ragged string drones, groaning low-end and sunken choirs called to mind visions of sodden grey and green moorland, slate barrows and knackered old mining equipment, like a late autumn wander through some of the more isolated regions of the North of England.

Krlic’s signing to Aurora Borealis, generally known for its involvement with metal and avant-drone, immediately called forth comparisons with the likes of Sunn 0))), and the witchy imagery couldn’t help but bring to mind the dusty, reanimated samplescapes of Demdike Stare. But what’s proved so remarkable about The Haxan Cloak is how it’s rewarded repeated listening. Although he recorded it by himself at home – far from your average soft-synth toting bedroom musician in 2011 – Krlic played every instrument on the record himself. Dominated by scratchy violins and the constant tectonic rumble of cello, like Richard Skelton’s music it feels less like a straightforward set of compositions than a series of explorations – the recorded format used to fully exploit the resonances of various instruments.

As a result it’s a beautiful, texturally rich album that revels in the tiniest of details. Each piece bleeds into the next, both musically and in terms of track titles (‘An Archaic Device’ into ‘Burning Torches Of Despair’, for example), slowly building to album centerpiece, ‘The Fall’, where a great choir of ghosts looms into the view through the mist. Played at high volume, it’s a completely immersive listen from start to finish.

Since the album Krlic, who’s based in London, has been playing live shows and working on a new record. His gigs have leaned further towards more rhythm driven material (examples of which can be found on his equally excellent Observatory EP, which he describes as "my interpretation of a Skaters record"). Since The Haxan Cloak will be occupying a strong position in the Quietus’ albums of the year, and as we’ve booked Krlic for a show with Perc at the Garage on 16th December, we thought it was high time we sat down and spoke to the man himself. We spoke about how the Haxan Cloak project came about, his obsession with bass and, more surprisingly, Soft Cell’s Marc Almond.

How did you first get into making music?

Bobby Krlic: Since I was a kid I’ve always been surrounded by music. My dad plays guitar, and my mum used to be a Northern Soul DJ when she was a kid.

Interesting story: my mum, when she was 14/15, she was from Leeds and she was friends with Marc Almond. She used to DJ Northern Soul, and Marc had just started Soft Cell. He said to my mum ‘We want to do a cover of something, but we don’t know what to do. You know all about soul and that stuff, I’ve got no idea about that’. And she gave him the 7" of Tainted Love, saying ‘Have you heard this song…?’ So my mum is single handedly responsible for that [laughs].

I think my dad put a guitar in my hand when I was about six. Then when I got to about 16 I started listening to a lot of electronica, and a lot of rap and hip-hop, and I was fascinated by vinyl so got some turntables for Christmas. I was making folky, violin and guitar electronica [using Reason] for years, then I went to uni. I did music and visual art, and I learnt about loads of stuff that I’d never even considered – listening to certain pieces and thinking ‘Wow, you don’t even need to use anything’ [to make music]. It was the first time I’d ever thought that you could conceptually think about music, which kind of sounds really stupid.

It’s a really naive, childlike view of music, but all I ever wanted to do was emulate people I watched. I just wanted to make tracks with good beats, I just wanted to play in clubs and I just wanted to make people dance. But going to uni and having this whole other aspect of sound was crazy. That changed the way I thought about everything, I started experimenting with different tones, looking at how sound is not only aural but can be very physical, it can have a real physical effect. That led me to where I am now.

You played all the instruments on The Haxan Cloak.

BK: The one thing I’m really proud of about that record is that there’s not a single sample on there. But at the same time I’m absolutely not against sampling. There are people that do it in absolutely astonishing ways. When you look at someone like J Dilla for example – it’s crazy, you listen to things like [Donuts] and then listen to the original samples, and I think ‘Man, how did you have the insight to find that tiny bit and make that out of it?’ That’s a talent in itself. That’s something I’ve never been able to do, so it makes sense that there’s no samples on there. It’s not the way that I think about stuff.

So how long did it take to put it all together? Cello and violin aren’t the easiest musical instruments to learn without sounding like they’re screaming at you, that can’t have been an easy process.

BK: Not really. I think I’m quite fortunate in the sense that, without sounding big headed, I’m quite adaptable to different instruments and I haven’t really encountered many things that I can’t get a tune out of. Yet.

In my first year of uni I bought a really cheap violin, and I couldn’t play it properly because I couldn’t get my hands around it, so I used to hold it like a mini-cello [laughs]. I used to sit and learn Dirty Three songs, and just play along. Then I bought a cello, a) because of the frequency, because I wanted something lower, and b) just because from my early violin days this [mimes playing cello] seemed like a much more adoptable pose than this [mimes violin].

I started the project in my last year of uni – that was when I first very loosely started forming some of the songs. When I finished I had no money, but I had very wonderful parents who allowed me to move back home. My dad works for himself from home and he has an office in the garden which has two separate rooms, and he allowed me one of them to use as a studio, so I just brought all my stuff home and set up. Every day I’d go in. I was quite regimented.

Even [after signing it to Aurora Borealis] the album wasn’t done. I needed it to be as good as it could possibly be. It took another year of me tweaking stuff. I think I even made two more songs. That’s when all the choral elements came – a friend of mine Mikhail [Karikis] who releases on Sub Rosa, he was a tutor of mine at uni, and we’d always kept in touch afterwards. He was working with these choirs at the time. I knew they had some downtime so I sent him some songs and detailed notes of what I wanted. Because I can’t really write music that well, and especially not for voice, I kind of just drew things. He interpreted that and sent me back these files and I was just astounded.

The response to the album has been pretty great though, right?

BK: It’s been really surprising. I thought at best people might say they thought it was a lame version of the last Sunn 0))) album. That really terrified me when they brought that record [Monoliths & Dimensions] out, because I was way into writing my record then, and they were doing these things with strings.

It sounds completely different, though. It reminds me most of Richard Skelton. They feel similar because they’re very concerned with space and texture, and interested in exploring the resonant properties of different instruments. Especially when you turn the volume up. Skelton’s like that – he goes out onto the moors and plays instruments in loads of different spaces, and sets mics around to record them, playing with the natural resonance of these spaces.

BK: That’s really something I was trying to do with the record. It’s kind of a continuation of something I was doing for my degree. I’m half-Serbian, so for my degree piece I took a piece of Serbian war poetry. Traditionally when the Serbians read these war poems they’re accompanied by this stringed instrument called the gusla. It sounds like a screaming cat, it’s horrible. So I had this recording of it, and I had it playing through a speaker cone, and I placed the cone on my electric guitar and turned the volume up, and I took the output of the guitar and recorded it as it rattled thr strings. You could still hear the poem but it was all going through the guitar body. Then I took that and I played that recording through a mic’d up violin, and I took that then played it through a piano, then through a drum kit. Sooner or later you end up with just a wall of noise, and you can’t really hear anything. Then when it got to that point I recorded the sound of it being buried underground [laughs].

That’s kind of echoing what you’re saying, in terms of exploring the tonal qualities of instruments, because that’s what informed the way the sound would then be processed. There was nothing but the original instrument itself determining what the sound was going to be, and that’s what the whole record was about really.

The album’s quite a weird thing, because I was quite conscious of it not just being received as a metal record, just because it’s on Aurora Borealis.

Were a lot of the responses you got originally pegging that in a kind of context?

BK: They still do. It’s not a bad thing. But I think there’s so many different things that inform the record other than Earth, and Sunn 0)), and OM. And people say Demdike Stare, witch house, and it’s so far away from anything I was thinking about when I was making the record. Metal’s informed a lot of my life for a long time, but no more than anything else really. I’m a massive, massive dance music geek as well. I’m a complete bass fiend. I’ll send my friends mixes of my stuff and ask them to play them through good speakers, and they’ll be like ‘Dude, what’s with the bass’? I’ll be like ‘What do you mean? You can’t ever have too much bass!’

First and foremost [making music] is about keeping yourself excited. Because if I’m not excited then what’s the point? The next record is not going to be anything like [the first]. I could do [the same record] again, or a continuation of that, but I don’ t think there’s any need to. The bands that I really love are always bands that have longevity because they’re pushing themselves. That’s the kind of artist that I want to end up being – someone who’s constantly just pushing what’s exciting to them.

The live sets I’m doing now are quite different. It’s quite a funny position for me to be in. I’m not saying [the album]’s done tremendously well but on a personal level it certainly has, and people have written about it who I really respect, and said really nice things. From that point of view, I certainly don’t want to alienate people [by playing completely different live shows]. It’s more just me going, you know what, I have a platform now to try things, and in front of quite a receptive audience.

You studied sound and visual stuff at uni – there’s obviously a really strong visual aspect to the record. There seems to be this really strong aesthetic running through everything – this sense of the occult, the name ‘The Haxan Cloak’.

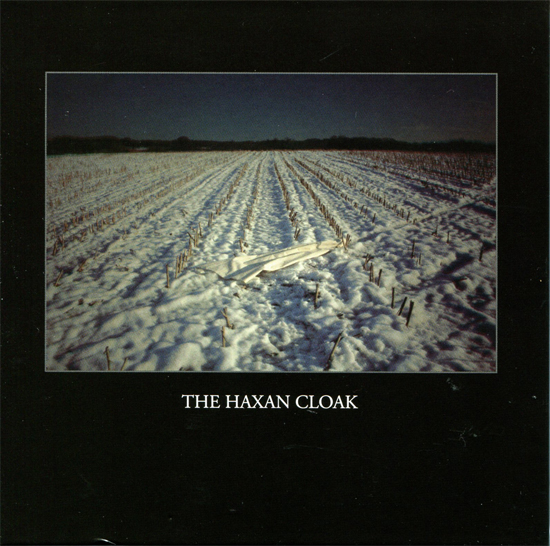

BK: On the one hand I guess it’s quite contradictory of me to go ‘Oh, it’s not a drone record, it’s not a metal record’, and there’s all this stuff going on. But funnily enough the main kind of impetus for the aesthetic and design of this record was Joy Division records. There were two record covers – Closer, and the ‘She’s Lost Control’ single, that had these really sparse covers. That’s all we talked about for months when planning the design – ‘it’s got to look like this’. But not just to copy – it’s just that they’re so refined, [the Joy Division covers], they’re so simple, but they allude to so many different things that could be going on.

It’s the same with the music. I don’t think it’s an album you can necessarily just sit down and listen to, and be like ‘Ok’. Many family and friends, I’ll give them the album and be like ‘What do you think?’ And they’ll be like ‘I’m going to sit down and listen to that again’. They haven’t said they like it or don’t like it, just that there’s something there that requires further listening. I wanted the artwork to be the same thing. With the current climate of the music industry, if you’re not going to produce a record that covers all the bases, every aspect of putting a record out, there’s no point in doing it.

So are you finding time to record new music in amongst all of this?

BK: That’s kind of what I’m doing. I’m trying to incorporate new material into the live show, and I’m underway with the new record. I’m in the process of signing a deal with someone, which I think is going to be quite a surprise for people. But really, really exciting. Next year’s just going to be super busy.

The Haxan Cloak is playing at Corsica Studios tonight, Wednesday 30th November, with Roll The Dice and Blanck Mass (DJ)

The Haxan Cloak plays for The Quietus at the Fred Perry Subsonic Live event at the Garage on Friday, December 16th. To find out how to get tickets, go here