‘Fisherman’, the most famous song by The Congos and the opening track from Heart Of The Congos, is well known and loved enough to be considered an absolute classic within the relatively large field of vocal reggae. Bizarrely however, it is rarely heard outside of that context. Everything is present and correct for not just this song but the album as well to be rightly considered high watermarks of Jamaican music. Heart Of The Congos was produced during 1976 and 1977 by Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry in his Black Ark studio in Kingston, Jamaica. House band, The Upsetters, were on unbeatable form, containing as they did Ernest Ranglin, Sly Dunbar, Mikey Boo, Boris Gardiner, Geoffrey Chung and Winston Brubeck amongst other peerless musicians. The song writing was pre-eminent, with the unusually long gestation period of three years helping shape this process as well as the writing of the vividly imagistic “chuchical” lyrical content.

Arguing over what is the greatest reggae album ever is too Sisyphean a task to be worth spending much time on but regardless, Heart Of The Congos has as much claim as any other LP and much more claim than most to the title. (It is certainly the author’s favourite reggae album, for the little it’s worth.) Like many other outlier albums in any genre from Loveless by My Bloody Valentine to C’est Chic by Chic, it is a strange mix of the starkly futuristic and comfortingly traditional in terms of production. Or in this case the mix between the far reaches of vocal and dub reggae.

The tradition here comes from the combination of the myriad singing voices marshalled in sweet, almost ecstatic union. Cedric Myton’s falsetto rings as clear as struck lead crystal and fuses perfectly with Ashanti Roydel Johnson’s rich tenor but even this beautiful pairing is pushed further and further aloft by other voices. The main auxiliary member of the group is Watty ‘King’ Burnett and his rich, earthy baritone is what gives this roots music its roots, while Black Ark favourite vocal group The Meditations give heavenly support throughout. Among the guest singers, the most striking is Gregory Isaacs who lends his liquid honey tones to ‘La La Bam-Bam’ – this is just one small reminder of why he will always be remembered next to Horace Andy as one of the great Jamaican soul singers.

The futurism we know about. The three dimensional presence of this record, the tangible spatiality of each drumbeat, guitar strum and bass throb that you can wade languidly through speak clearly of a production genius not only ahead of the curve, but in a field all of his own. All of which is rendered more impressive by the fact that half of Lee Perry’s equipment was, if not outright obsolete, hardly cutting edge. These gizmos and gadgets included the Echoplex tape delay reverb unit built ten years earlier; a mass market TEAC reel-to-reel – this kind of four track was still being used in Abbey Road in the mid-60s, but by the time of The Congos was only really common in homes, youth clubs and schools, not really in professional studios; and an admittedly up to the minute Soundcraft mixing console. One effect that he used a lot was the standard psychedelic effect of phasing, but he had some behind the scenes help with this. As well as a standard Mu-tron Phasor, a guitar pedal designed to make synthesizer-like noise without the use of a synth, Perry had an early prototype of the company’s Mu-tron Bi Phase which provided a then-revolutionary number of two phase-shifting circuits, which allowed him to dramatically lower the depth of the phase and to phase two instruments in time rather than just one. This synchronously shifting effect, in the late 70s, is what was blowing people’s minds.

But when you combined these two oppositional forces…

Drop the needle onto ‘Fisherman’. The drums have all been bounced over to one channel on the TEAC, causing a wicked amount of degradation in the sound; the opening snare hits have been wrested of all harshness and clarity; then the reverb sees them crumble away into darkness. These are the abyssal depths of the track. Plumbing these waters are the basslines, one fuzzy and immersive, the other squelching and funky, carving out yet more three dimensional space (two different bass players were used on two separate days of recording – if this was an accident, it was a happy one). The delicately phased guitar lines sparkle above this, like sunlight on a calm sea surface, dappling the space below. The voices arrive staggered, creating further space, Watty’s rumbling bass and then Roy’s clear tenor. They may sing about the sea-bound man in the third person, but really it’s The Congos themselves who are the fishermen, and the listeners the fish. They are, as the bible would tell you, the fishers of men. And this is evangelical, churchical music… just perhaps in more of a Rasta style than we had been previously used to.

The song starts with an exhortation to a Rasta fisherman – who already has three children, with another on the way – to bring back enough food for his family, before making a direct comparison to the apostolic fishermen Simon (aka Peter), James and John who have countless hungry “children” to feed (“lots of hungry belly pickney ashore – millions of them”). The Congos, being based in a fishing port, are keen for people to realise that this is a parable, and throw a concrete suggestion into the lyrical mix: that the fisherman might actually provide for his family by going to see Quaju Peg, the collie man, for some of his fragrant produce to sell. The song ends with the Congos urging the fisherman to reach higher ground because rain is coming, perhaps the forewarning of an apocalyptic event comparable to The Flood – a theme which is returned to again and again later in the album. The lyrics plumb depths under their deceptively calm surface, just like the music.

In reality, though, it was Babylon itself which stopped the world from embracing the album immediately. It never had the advantages of other Black Ark classics such as Island’s backing for the release of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ Natty Dread or the patronage of The Clash for Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves. Instead, petty label disputes and a glut of inferior bootlegs stopped the album from being a hit in either Jamaica or the UK. Mick Hucknall’s excellent Blood And Fire reissue label did a lot to reverse the damage with a great double album version in 1996, and now perhaps the status of the record can be downgraded slightly, leaving Max Romeo and the Upsetter’s War Inna Babylon as the reggae album most unjustly overlooked by the mainstream. When speaking to them, The Congos told me that they are planning on reissuing the album themselves again soon and bringing a band to the UK to tour the record. Delightful news indeed.

Recently the group recorded an excellent album (Icon Give Thank) and documentary film (Icon Eye) with Texan psychedelic musician Sun Araw and LA-based soundtrack artist M. Geddes Gengras as part of the FRKWYS series. The musicians will be playing together at a hotly anticipated live event (also featuring in a DJ capacity the mighty King Midas Sound with Kevin Martin at the controls and Hitomi on vocals) at London’s Village Underground on June 22.

In the first of two features anticipating this event, I talked to Ashanti Roy and Cedric Mytton about the past and present of The Congos. (Next week I will be speaking to Sun Araw and M. Geddes Gengras about the FRKWYS project.)

I was really surprised to hear that you were working with Sun Araw and M. Geddes Gengras. How did this collaboration come about?

Ashanti Roy: They’re fine men. Those guys are some Congos fans, you know? They came down to Jamaica and tempted the Congos into doing some new tracks for their new album. So we did that.

Cedric Myton: Those guys from America were fans of ours. They were fans who became our friends. So we thought we should do some work together.

Did you feel that your style of music and their style of music was complimentary?

AR: Well, their style is a kind of new style but I love it. It’s creative. But the Congos are adaptive. We can adapt to any kind of rhythm, you know? The rhythms on them Sun Araw and M Geddes Gengras songs and the sonic environment they create… it sounds very interesting!

CM: Well, to be honest, their music is a new experience and a new vibe for me but music is still the one way. It is universal. If someone introduces you to something new and it’s not going to hurt you, go along with it and see how far you can go.

How did they fit in with your lifestyle? It must have been a massive change in pace of life for them to go from living in somewhere like Texas to staying with you in the Congos HQ for three weeks in St Catherine, Jamaica.

AR: Yes. Our daily routine is that we train, we meditate and we go to the sea. I took them to nice places, they saw some nice sights while they were here but they were in the studio for most of the time working.

CM: People always love the African and the Caribbean lifestyle, especially foreigners who come to Jamaica. They like the scenery. They like the music. They like the marijuana. And the food. Don’t forget the food. And the people and the culture as well. So when you come here, things can only get better! I live in Jamaica now. I was in America for a while but I feel it was closing in on me. I needed to come back to my roots. I had to work. Jamaica helps me work. In two and a half years I made 11 albums. At the present moment in time I have six albums that I haven’t released.

How different is it round St Catherine now from when you first met?

CM: Well, it’s the same in a way with just a little improvement with some houses being built in the area. There has been a little improvement but it could be better if the government would do what was good for the people.

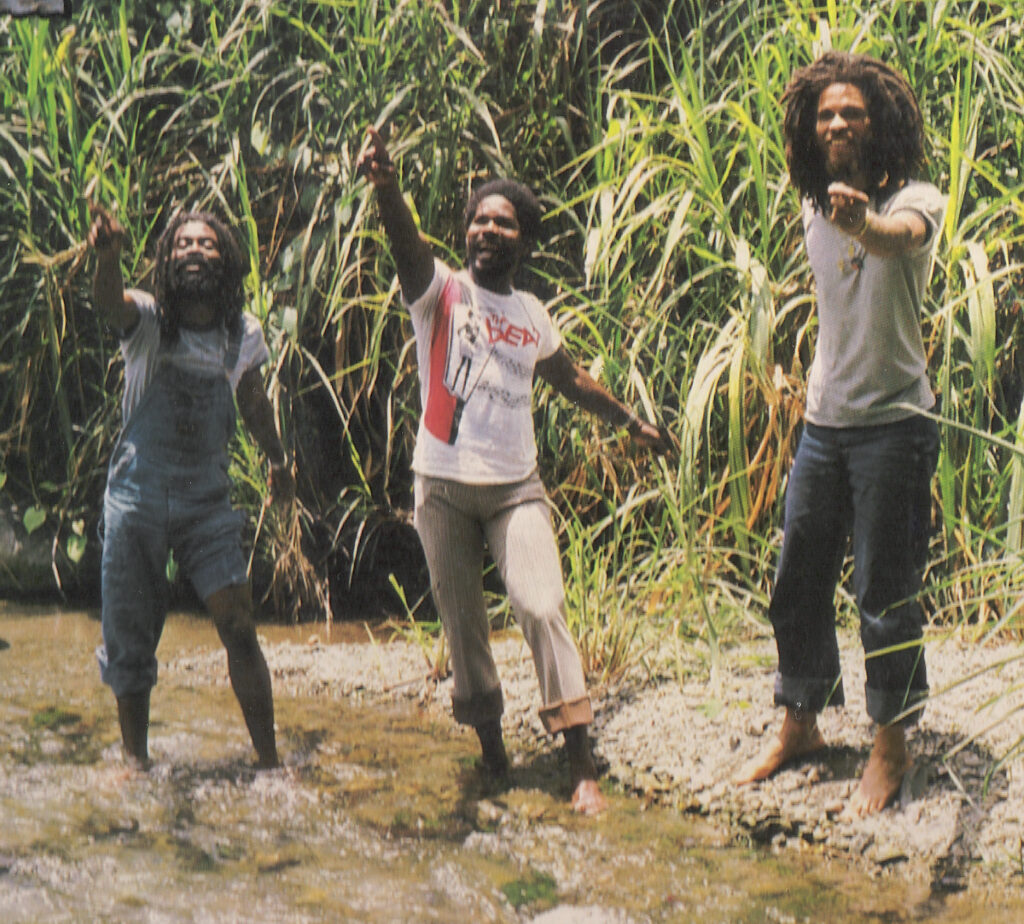

Play this rarely seen 1980 French documentary Jamdown from 42’04", to see The Congos in the studio and playing ‘Fisherman’ on the beach

Do you think that the Congos message today is unchanged from what it was in the 1970s?

AR: Yes. The message of the Congos is for today. Our message is just starting to take shape out there – it applies to what is going on in the world today. Out there I can see those songs [from Heart Of The Congos] right now. I see days chasing days and still I can see thieves in the vineyard, trying to spoil the harvest. Like we say on ‘Fisherman’ and ‘Congoman’, there are lots of hungry belly pickney [children] out there. We have a recession over the whole world, and there are people starving all over.

CM: Yeah, it doesn’t change. We have one aim and one destiny and that is our spiritual work. The work of the Congos hasn’t changed and the message of the Congos hasn’t changed. It is about one love. It is about spirituality. It is about repatriation and back to Africa. And it is about the development of the black people, not only in Jamaica but all over the world. We speak to the world.

How did you two meet?

CM: It started with this group The Sons Of Negus… Actually, before that I had a group called The Tartans, with Prince Lincoln Thompson, Devon Russell and Linburgh Russell, and we played rocksteady. After that I met Roy in 73/74.

AR: I’ve known Cedric for a long time now. We almost grew up together. He’s from St Anne’s Harbour and I moved to St. Anne’s Harbour from Hanover. I came to town when I was a youth and we hooked up by doing garments and then we started to sing together. I played the guitar and both of us sang so we would get together, rehearse and make some songs and then we went to the mighty Upsetters and it started from right there.

You knew Lee Perry from school didn’t you Roy?

AR: Yeah, me and Lee Perry go right back. We went to the same school and we were born in the same parish. Lee was older than me, I was born in ’44. [Perry was born in ’36]

What was he like in school?

AR: He was great man. He was skilful at everything, like playing marbles and doing jigsaws. He was a very skilful little youth. And we used to dance together. We were the best dancers in our parish and every time they had the sound system dances we used to go there together and mash up the place.

So musically you two gelled with each other quite easily?

AR: Yeah man, when me and Cedric make music it’s easy for us, you know? It’s very easy. We just meditate and when we get the rhythm we start to write the lyrics straight away. Our lyrics are things that you can relate to. But it always starts with the fundeh drum to make the riddim. Check our beats, they all come from the fundeh drum. This is the Rasta drum. Even Bob Marley used these Rasta vibrations to get his message across.

CM: Yeah, yeah, yeah! We were saying the same things about Rasta culture and we were both churchical and from the Nyahbinghi tribe.

Which were the first songs you recorded as the Congos?

AR: Ah let me see now… you’re talking about a lot of songs… ‘Solid Foundation’ – that was the first song we recorded so then we took it to Scratch and then came the Heart Of The Congos album, ‘Fisherman’ and everything like that.

CM: The first songs we recorded were ‘Solid Foundation’, ‘Children Crying’ and ‘Congoman’.

Is ‘Fisherman’ based around a traditional song where you’ve rewritten the lyrics?

AR: [laughing] Yeah man, ‘Fisherman’ is a very creative song. We all come from a sea port town, so we just came up with that song just like that.

What age were you when you first started to take the Rastafarian religion very seriously?

AR: 16, 17 we started work very seriously at it and then when we were 24, 25 we started to work very, very seriously at it.

CM: From about 17/18 years of age.

Did you see the Congos as an extension of your spiritual beliefs?

AR: Yes, the Rastas are very spiritual. We come from the Nyahbinghi [one of the three mansions of Rastafari] and from there we create vibes, so this is part of our religion.

What lessons could the world in general learn from the Rastas?

AR: The benefits are spiritual awareness and a pure heart. It teaches us to love our brothers and sisters. It tells us to do unto others as you would have them do to you.

How long did it take you to make Heart Of The Congos?

AR: It took three years to make that record because Lee is a man who likes to work and work and work. And then listen. And then work some more. Because he is a man who likes perfection.

One of the reasons the album works so well is that the music is very modern for its day but the vocals are very traditional and sweet…

AR: Yes, yes. We put in a lot of work on that. We were in the studio all the time. Every single day we were in the studio to share our vibes with each other.

CM: Let me tell you, we did a great part of the work but Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry did a great part of the work too. Two thirds of the work on that album was us, but the next third was down to Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, trust me.

Obviously no mention of Heart Of The Congos would be complete without mentioning Watty Burnett, the third voice on the album and your bass singer – how did you meet him and the other vocalists on the album like The Meditations?

AR: We were in the same studio as The Meditations. They were the big artists at the time and Watty was there too. So when we started the album, we went to Lee Perry’s home where he had his studio, and Watty was there also. So I sing tenor, Cedric sing that high pitched thing and then we needed a bass and Lee said you have to try Watty… and it worked. It just worked man. We worked together as a trio.

CM: Great singer, great, great singer. Watty Burnett is the greatest bass singer in Jamaica of all time.

And of course you had an astounding band in The Upsetters who were unbeatable at the time. You had Boris Gardner on bass, Sly Dunbar on drums…

AR: Ernest Ranglin!

CM: We recorded the ‘Fisherman’ song over two days. On the first day it was Boris Gardner and then on the second day it was Geoffrey Chung, so it had a different flavour on the second day. We really had the best musicians… the cream of the crop. Ernest Ranglin, Winston Brubeck, Keith Stewart, Billy Johnson. The greatest musicians in Jamaica.

I bet they must have been a fearsomely tight band…

AR: Yeah, in those times we were like one big family you know. And it goes on until now. When we see each other in the streets, it’s just like the olden days man. We are good friends. We are brothers and sisters.

CM: You had to come good if you were going to play with Lee Perry.

So many all-time great albums came out of this particular time and space, such as Max Romeo’s War Inna Babylon and Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves. What was it about Lee Perry’s Black Ark Studio that produced this almost magical property for records?

AR: You know, at the time we were using a four track to record with, so every musician had to be precise with what they were doing. So when we would work, we would go over and over and over the music first. It wasn’t like it is now when you can lay down the rhythm first and then come back to do the voice track. In those days everyone, drums, voice, guitars, everything would have to go together, so everyone has to be precise and no one could make any mistakes. It was kind of nice, it created good vibes. Everyone put their own vibes into the recording and that works man.

CM: [laughing] It’s all mystic. It’s all magic. It was destiny that it was to be like that. It was part of the plan.

So you only had use of a four track…

CM: [roaring laughing] … but he could work magic with those four tracks!

Do you know why Lee burned his studio down?

AR: That was another thing you know? When Scratch got into his vibes and burned his studio down, by those days we were away doing something different so we don’t even know what went wrong, but it was all the vibes. I don’t know if the vibes were wrong or how they went wrong because we only did Heart Of The Congos and some singles with him.

CM: He had to do what he had to do to be alive today. Bob Marley couldn’t be alive today. Bob Marley could not be here today, but we are here to give this testimony. Lee had to do what he did to be where he is today.

Socially, what was it like being a musician and a Rasta in mid 1970s Jamaica? How did you get on with the mainstream of Jamaican life?

CM: Rasta culture is the mainstream culture in Jamaica. Any other culture in Jamaica is adapted culture. In Jamaica you have a lot of different tribes from the Maroon to the different tribes of Africa, so there is a lot of culture in Jamaica. And our main problem is that language. We only speak one language but really we should all speak all languages of the world beause we don’t speak the same language.

AR: Everybody in Jamaica loves the Congos.

But didn’t you have a fraught relationship with the police in the 1970s?

AR: No… well, once they came up here with the bad vibes and they got Cedric and cut his hair off, but that was way back in the 80s you know? Because there had been an uprising in Jamaica and they pinned it on the Rasta Man. But you know, we got rid of that and right now, Rasta Man gets a lot of respect from all over the world. The people of the world can see that Rasta Man is a spiritual person and is interested in truth and rights.

CM: That was one day where they were trimming Rastas. The devil was in full swing at that time. The devil was in his prime. They got me and trimmed me and that was that.

Do you feel that your religion is taken more seriously now?

CM: Yes of course. It’s been growing, growing, growing more and more.

Were you disappointed that Heart Of The Congos didn’t come out on Island in the end?

AR: Well, it was out there for a long time and we didn’t make any money from Heart Of The Congos. All different kinds of companies put it out but the old saying goes, ‘What will be will be.’

CM: Yes I was disappointed. It was all a conspiracy. Lots of people conspired against the album. The music was great. The lyrics were great. The talent was great and the production was great. It was all churchical inspired. But no one could buy it.

Do you get some comfort from the fact that more and more people round the world have heard it since?

CM: Yeah, man, it’s a pleasure. Look – Blood and Fire did a very good job when they reissued the album, they did a lovely job. The only problem we have is VP Records, because they have been pirating the albums for years. They pirated before we signed with them and then after we signed off they still pirated the work. And they still haven’t paid us what they owe us. But that is part of work.

Many of the people on the album went on to become famous in the UK. For example, Gregory Isaacs sings on ‘La La Bam-Bam’. What was he like?

AR: Gregory was my brother. He used to live at my house. When I played guitar, he would practice in my yard as well.

CM: Oh Lord, he was one of a kind. Gregory Isaacs was one of the kindest musicians to come out of Jamaica. After Bob Marley, Gregory Isaacs is the next in command. He was the most generous… and he was a rude boy!

Also talking of people who became famous in Britain, you have Boris Gardner playing bass here. He was a great bass player back in the day, even if he’s more famous in the UK for having a hit with ‘I Want To Wake Up With You’..

AR: Very good bass player. A very good international musician. I like him. I saw him a couple of nights ago and he’s the same Boris as he was, no different, you know?

CM: A number one bass player.

If I have one hope about this feature, it’s that someone will read this and go out and get a copy of Heart Of The Congos if they don’t own it already…

CM: We’re going to come back with this album! So you can tell the people – look out, it’s coming again. There is going to be a new reissue and we’re hoping to do a Heart Of The Congos tour in England. It might be arranged through the Congos’ label…

If someone listens to the album today for the first time what do you hope they get from it?

CM: I hope they get that it’s for the people. It’s the art of the people. It’s the culture of the people. The Heart of the Congos is for the people. One love. Peace.

Thanks to Andrew Harrison