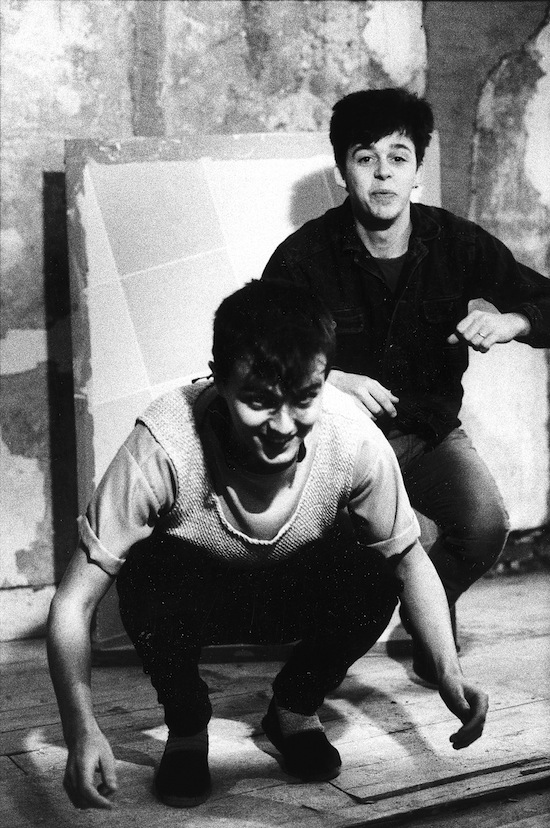

There was a time, in the mid 1980s, when Tears For Fears were inescapable. Formed in 1981 by two unprepossessing youngsters from Bath, Roland Orzabal and Curt Smith, their ascent to global stardom on the back of their second album, 1985’s Songs From The Big Chair, was accompanied by massive success with at least two songs that remain instantly familiar even today: ‘Shout’ and ‘Everybody Wants To Rule The World’.

But it was their debut, 1983’s The Hurting, which first established them in their homeland. It followed the unexpected success of ‘Mad World’, a morose but strangely infectious single that spoke of how “the dreams in which I’m dying are the best I’ve ever had”. The album itself, meanwhile, was entirely conceptual, honing in on a particularly unusual topic: the psychological traumas of childhood and their long term effects, something with which both musicians were more than familiar.

They weren’t the first to explore the subject, of course: John Lennon had covered similar territory on John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band a decade earlier. Others, too, would take inspiration from their shared muse, psychotherapist Arthur Janov: Primal Scream, for example, borrowed their name from his most renowned book. For an unknown act, however, it was a significant feat to have stormed the charts so convincingly while addressing such a complex theme. Their often bleak synth-pop, too, was radical at the time, something that it’s easy to forget: though it was inspired by Gary Numan, and others – like Ultravox and Soft Cell – had already helped establish the format.

Listening to The Hurting three decades later, Tears For Fears’ obvious confidence in their work continues to shine. Whether it’s the disconcerting pop of ‘Mad World’, ‘Pale Shelter’ and ‘Suffer The Children’, the uneasy experimentation of ‘The Prisoner’ or the naked emotion of ‘Ideas As Opiates’ – its title taken from one of Janov’s chapter headings – the album represents a milestone in the development of 1980s pop. They would continue to enjoy commercial success with Songs From The Big Chair and The Seeds Of Love (1989) before the two of them would separate, leading to a further brace of Orzabal-fronted albums that never quite captured their early magic. The Hurting, however – compared at the time to Joy Division and Echo And The Bunnymen – remains Tears For Fears at their purest.

“When the first song was written to the time we were on Top Of The Pops,”Orzabal says, “that’s the ages of 18 to 21. That’s the ages when most people go to university. Or used to! That was our education, and by the time we got to 21 we’d become professional musicians. It became a job. After that it just became more and more watered down and more mainstream. And that’s a fact. It’s just the way it ended up…”

So, with a deluxe box set of their debut album on the way, a new one finally in the works – their first since their reunion for 2004’s Everybody Loves A Happy Ending – and the recent appearance of an unexpected, unlikely cover version of Arcade Fire’s ‘Ready To Start’, the time is right to join Orzabal and Smith where it all began – a council estate in Bath – as we retrace their steps on the route to success…

Familiar Faces

Roland Orzabal: Co-founder of Tears For Fears; main songwriter and co-vocalist. Co-produced Emiliana Torrini’s Love In The Time Of Science in 1999.

Curt Smith: co-founder of Tears For Fears and co-vocalist. Has released four solo albums, most recently Deceptively Heavy in July 2013.

Richard Zuckerman: A&R for Precision & Tapes Records, part of Pye Records. Signed Orzabal and Smith’s first band, Graduate. Moved to New York to work for CBS International between 1985 and 1989, before executive producing Celine Dion’s first two English language albums. Currently sells real estate in Canada.

David Bates: joined Phonogram as an A&R scout in 1976, signing Dalek I Love You, and, two years later, Def Leppard. Picked up The Teardrop Explodes soon afterwards, then Tears For Fears in 1980. Set up db Records in 1998 with producer Chris Hughes.

Chris Hughes: former drummer and producer of Adam And The Ants a.k.a. Merrick. Produced The Hurting and Songs From The Big Chair. Co-founded db Records with David Bates in 1998. Also produced Electric Soft Parade’s Mercury Music Prize nominated debut, Holes In The Wall, in 2002.

Memories Fade But The Scars Still Linger

Roland Orzabal (RO): Curt and I are both the middle of three boys, and in my situation there was domestic violence. There are a lot of people who have difficult childhoods. My childhood was the same as my two brothers’ and they didn’t go around moaning about it! We can all make a big deal that we were council estate kids. But that was the biggest thing that upset me, that my Dad would be physically violent towards my Mum. And it got so bad that in the end she left.

Curt Smith (CS): We both grew up primarily with our mothers because our fathers were absent. (My childhood) was spent growing up on a council estate, albeit in Bath, which probably has nicer council estates than some parts of the country.

RO: Curt grew up in a place called Snow Hill, and it’s not so bad now, but in the early days it was not like the centre of Bath where you have all the beautiful touristy buildings. It was a block of flats. Several blocks of flats. Bath is lovely now, but it just didn’t feel that way at the time.

CS: We had nothing, so we would go and steal things. It was a very poor, basic upbringing, but it taught to you to be independent.

RO: [My parents] ran an entertainments agency for pretty much Working Men’s Clubs. We had a ventriloquist come round and he taught me ventriloquism. All the women were strippers. My Mum trained strippers and was a stripper herself, and my Dad used to enjoy that as well! It was very strange. We were kept out of the way while all that stuff was going on. The weirdest part of my childhood was that any guys that came round were generally guitarists and singers. So as a young kid I was exposed to people playing and singing, and my father would get out a tape recorder and record them, and sort of say, "No that could be better", or "You could do that again." I grew up idolising one singer in particular, who was the antithesis of my father. Black belt at judo, big guy, sounded like Elvis. I thought, "Yup, that’s what I want to do."

CS: Roland wasn’t originally from the council estate I grew up on, but he’d moved up at the age of 11 from Portsmouth, where he was from. There were two major comprehensive schools in Bath, so we weren’t at the same school.

RO: I started playing guitar, learned three chords and started writing songs. My first love, believe it or not, was country and western: Johnny Cash and a bit of Elvis. I always found myself, even if I had a group of friends – four or five people – we would end up singing and banging stuff. And I was always like a ringleader. You know me… So then, a bit later, because I was more advanced on the guitar, at school I gave guitar lessons. The guys who were learning guitar, we’d form a band, and it would go on and on like that. There were always a lot of kids who wanted to learn, and I could teach them a few things, and we’d end up being in a band. I was best friends with a guy who I taught to play bass, and he went to my school. He knew Curt from his previous school, so, when we formed our first heavy metal band at age 13, 14, we met through our bass player, Paul.

CS: They came to my flat one time and heard me singing along to a Blue Öyster Cult record, of all things, and Roland asked if I wanted to sing for their band.

RO: He was playing Blue Öyster Cult’s ‘Then Came The Last Days Of May’, and we were thinking, "Oh yeah, maybe [we’ve got] a lead singer here." So we were the classic Led Zeppelin format!

CS: [Roland] was kind of a nerd. He was more studious. Both his parents were very educated. Mine were definitely under-educated. So I guess, even though we grew up along the same lines, he was from a very different background. I was interested in reading – I’m interested in learning stuff, there’s no question about that – from a very early stage. But on a council estate it’s hard to find like-minded people. I think we were both like-minded people, but from very different backgrounds.

RO: I remember the first time I met Curt, he wasn’t allowed out because he’d been in a fight. He’d dumped someone down the stairs. Yeah, he was a lot more rebellious.

CS: It was nothing abnormal for a council estate. Luckily I charted a path out of it. A lot of these kids went on to just a life of crime. I was just trying to gain attention in whatever I could. I guess I could have gone that way, but I chose a different path. [Being in a band] was a legitimate way of getting attention. It didn’t involve breaking the law.

RO: It’s the attraction of opposites, isn’t it? I never looked up to him, but I’ve ended up in my life with people who are more fiery than me, and bring out the fire, like my wife. I didn’t marry someone timid and conservative. I guess it’s one of those psychic – relating to the mind, you know? – sort of things you bring into your life, things that hopefully bring the best out in you.

CS: We have a very, very similar sense of humour. Our main means of communication would be sarcasm.

RO: I was one of those people in school who used to work hard and then, when I was about 17, 18, I had a mental Copernican inversion, so instead of just following what I was being told and doing really well and getting ‘A’s, I just started questioning everything. We were reading a lot of existentialism, both in French and in English, so that kind of set me off.

CS: Those teenage years when you’re looking for all the answers…

RO: I had a guitar teacher, and she introduced me to a book called The Primal Scream (by Arthur Janov). And I read it, and it became my bible. The theory is called The Tabula Rasa theory, or the ‘Blank Slate’ theory. A child is born a blank slate, and then all the terrible things that happen to it – the childhood trauma and the rejection, not enough love – become suppressed and then turn up as neuroses in later life. The therapist would try to lead you to recall something that happened to you, and your way of mourning – and it’s a deep way of mourning – is that you actually cry. Not as an adult, but actually in a sense you’re going really, really deep.

CS: It’s not a novel idea. I just think Janov explained it in better terms than most people.

RO: I converted Curt, you might say. I suppose both of us were believing we were victims, so we would quite often try and convince other people of the validity of Janov’s ideas, but no one would… I suppose we were the only two. You know what it’s like when people have a specific belief and they don’t have any room for anyone else’s beliefs: it’s a turn off. And I was definitely one of those…

Richard Zuckerman (RZ): In about 78, 79, there was a guy called Peter Prince who ran the A&R at Pye Records, and I went and joined him as an A&R guy. Then they decided to split it into different labels, and I ran the Precision Records And Tapes (PRT) label. It was very small, just starting off, did a couple of singles and things. That was my start. There was a label called Rialto Records, and I signed them to Pye. That was The Korgis, and that’s what led me down to Bath. I think they were friends with Roland and Curt’s band, Graduate.

I went down and saw them in a club, and, for me, Roland in particular was the guy. Roland’s best friend was Curt, and then they had the other guys around the band, but Roland was the absolute star. He was the everything of the band. I’m a bit of a player myself, and when I used to hang with Roland the thing that struck me was the way he played the guitar, and the way he wrote songs. I couldn’t even discuss chords with him: he had open tuning, and his chord structures were bizarre and unbelievably weird. So I checked them out, and they had a little local following, and that was enough to know that I should get involved.

RO: So we signed a record deal with Graduate, miraculously.

CS: I think we had to wait for Roland to turn 18. I don’t think his mother was particularly happy about the whole thing. That was 1979.

RO: I suppose we weren’t a particularly serious group, and we were very, very much down the food chain when it comes to the authentic groups like The Specials and Madness and that kind of stuff. We weren’t very good. But we had a little bit of radio success in Spain, which was my first experience of hysteria and girls hanging outside the hotel.

CS: We actually had a number one hit in Spain!

RO: Previous to that I’d been unemployed. My wife had been working three jobs in bars and restaurants, and I got my first PRS cheque and I thought, "That’s a good job!"

RZ: The marketing was pretty bad. I just brought the single back from the UK, and I’m looking at the packaging and, erm… it’s pathetic! If you look carefully, the faces are just cut-outs! And that’s the sleeve! The thing about Pye was, by the time you got to the 70s, they were always known for being a singles company. They sold masses of things like ‘The Birdy Song’ and Lena Martell’s ‘One Day At A Time’ and things like that. I mean, millions and millions of singles! But we could never sell any albums. Certainly I don’t remember much being done about Graduate’s album.

RO: So we split from Graduate at the end of 1980.

CS: The upside of Graduate is that we learned that we were not made for travelling in minivans.

RZ: We did a little British mini tour, and they had a tour bus, and I followed them around in my car. I remember Roland sneaking away from the tour bus, and I drove him round the back streets of Newcastle – or somewhere, I can’t remember – and we were having a good old laugh. I think Curt was quite miffed that I took Roland and left Curt on the bus!

CS: Yeah, we learned a lot of things. And it was also an interesting time, because around then technology had just started taking off, in the sense that Linn drum machines and the need for a band really didn’t exist any more. Before then it was always kind of bands based around the studio, but Gary Numan changed all that. And we realised we wanted to concentrate on making really good records, something that lasts.

RO: We went to the record company, Precision, and we told Richard Zuckerman that we had split and we were going to do synth pop. And he was like, "Great, OK."

CS: At that point we didn’t even have the name Tears For Fears.

RO: I think we might have been called History Of Headaches for about two hours. It’s awful. But there were a lot of names in the offing. We weren’t really serious about that.

CS: Once I’d got the name Tears For Fears in my head, which was from the Arthur Janov book, Prisoners Of Pain, I told Roland. I think pretty much straight away we knew that was going to be the name.

RO: I thought, "Yes, that’s it!"

RZ: I had no problem with the band breaking up because for me it was always Roland. I don’t want to diss Curt too much, but they were friends. There’s no doubt that Roland was helping Curt along. He helped him to learn how to play bass guitar and gave him a job in the band. But it was all about Roland. Roland was the star.

RO: So Richard funded our first recording, which was ‘Suffer The Children’, with David Lord. We did that song, and we used the Graduate drummer, Andy, on it.

CS: David Lord went on to produce Peter Gabriel’s fourth album, and had produced a band called The Korgis, who’d had a couple of hits.

RO: Do you remember The Korgis? The other hit band from Bath!

CS: He had a studio in Bath called Crescent Studios. We’d done the Graduate album there.

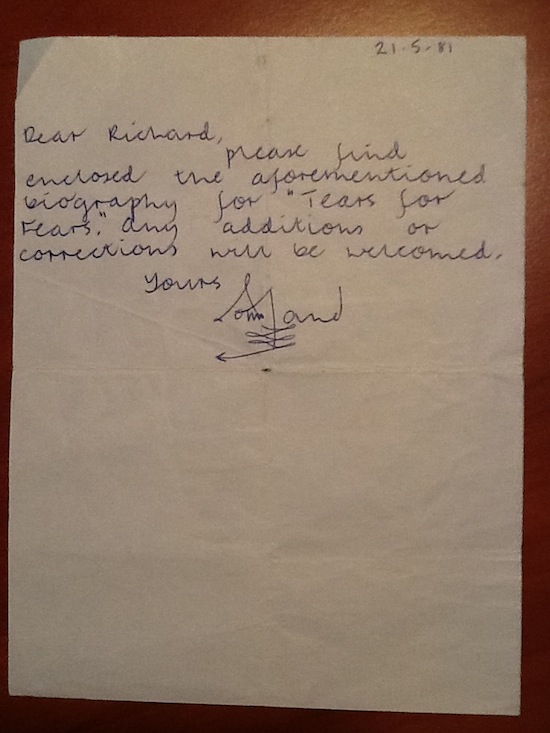

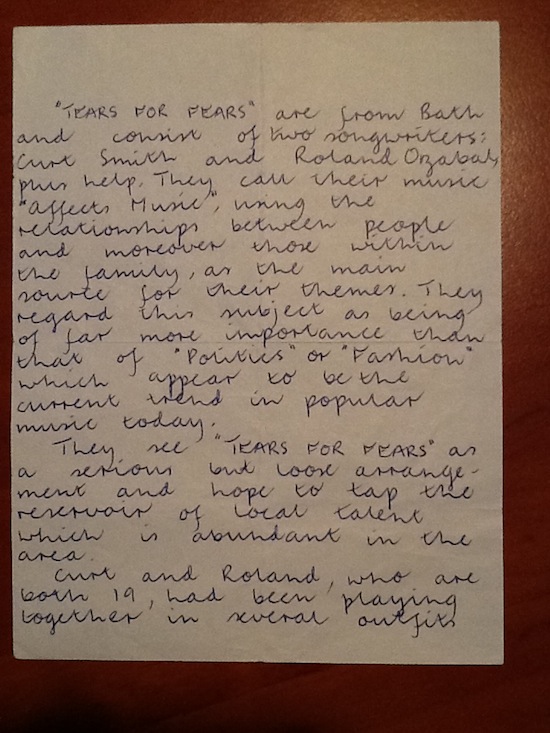

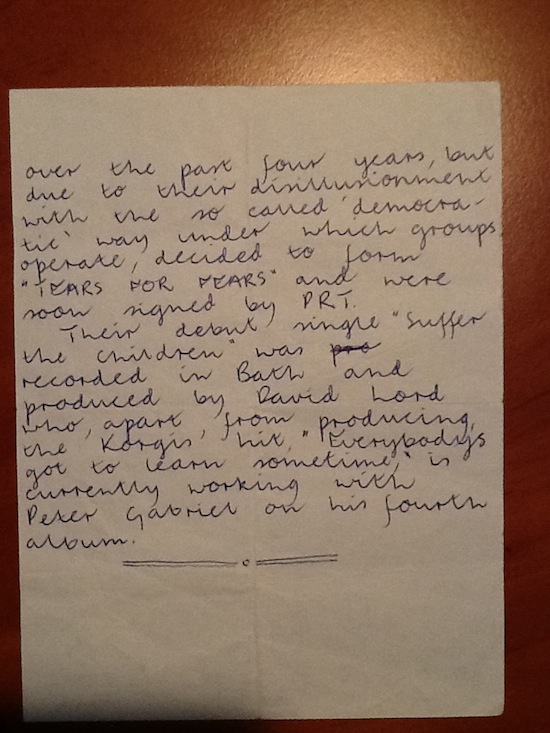

21 May, 1981

Dear Richard,

Please find enclosed the aforementioned biography for “Tears For Fears”. Any additions or corrections will be welcomed.

Yours,

Roland

“Tears For Fears” are from Bath and consist of two songwriters: Curt Smith and Roland Orzabal, plus help. They call their music “affects music”, using the relationships between people and moreover those within the family, as the main source for their themes. They regard this subject as being of far more importance than that of “politics” or “fashion” which appear to be the current trend in popular music today.

They see “Tears For Fears” as being a serious but loose arrangement and hope to tap the reservoir of local talent which is abundant in the area.

Curt and Roland, who are both 19, had been playing together in several outfits over the past four years, but due to their disillusionment with the so-called “democratic” way under which groups operate, decided to form “Tears For Fears” and were soon signed by PRT.

Their debut single “Suffer The Children” was recorded in Bath and produced by David Lord, who, apart from producing the Korgis’ hit “Everybody’s got to learn sometime” is currently working with Peter Gabriel on his fourth album. (letter pictured below)

RO: Then, if I remember correctly, Richard Zuckerman either got the sack or he resigned for another job. I don’t know. But what he did was let us go with the master tapes. So we had ‘Suffer The Children’.

RZ: They were slowly cutting it back, and eventually there was no real record company left. They weren’t signing acts any more, and I left to go into music publishing.

CS: We then luckily met a guy called Ian Stanley. He was kind of a rich kid who had been working with the old members of Graduate, and the old members of Graduate were talking me up, so he was interested and offered us the chance to record on his 8 track at home.

RO: Nowadays I can write very easily. There’s so many bits of technological inspiration. Ian Stanley’s studio was a godsend because there was access to a synthesiser and a drum machine. To actually sit at home with just an acoustic guitar was tough.

CS: So myself and Roland went up to London with, I think, just two songs to play to A&R people. We had well produced demos, which I think were just ‘Suffer The Children’ and ‘Pale Shelter’.

RO: From the Graduate deal, we had a relationship with a production company with Tony Hatch, composer of the Crossroads theme tune (and who had written songs for many Pye artists). He’d actually co-produced our (Graduate) album. He had a son called Darren, and we gave Darren the demo tape of ‘Suffer The Children’ and ‘Pale Shelter’. ‘Pale Shelter’ we did at Ian’s. We had a photo session done as well. Darren saw all the majors, but we had only two bits of interest. One was from Charlie Ayres at A&M, who was very nice, and the other was Dave Bates. And that was only, Darren had walked in, played it, I think Dave Bates had grunted, and Darren Hatch was halfway down the corridor when Dave ran after him. So by such thin threads we managed to get interest from Dave.

David Bates (DB): I don’t believe it was (Tony Hatch’s) son. It was a chap called Les Burgess. He was a song plugger from the publishing company. On that day he brought six cassettes of songs. Def Leppard was self-sufficient and wouldn’t use MOR songs in a million years. The Teardrop Explodes equally so. I thanked Les and said goodbye for another six months. After he had gone I thought about one of the cassettes I had heard, one in the middle of the pile. I called Les up and asked him about them. He told me they were two young guys, 20 years old, who lived in Bath. I told him I wasn’t interested in the songs, but the duo: could they be an act?

I travelled down to Bath to meet them and remix two of the songs to see if they could be singles. I had never heard Graduate. After a couple of meetings they told me about the band. They didn’t want to play me anything. So I had to go out and get a copy of the single. The sleeve gave a clue as to what it was going to be like.

RO: Dave came down. We did a bit of a remix of ‘Suffer The Children’. This was while David Lord was working on the Peter Gabriel Four album.

DB: When I got to the studio, there was Peter Gabriel. It was his engineer, David Lord, who engineered the session.

RO: It was great to work with him. He had a Synclavier, which was a very expensive precursor to a Fairlight. An amazing synthesiser.

DB: Hearing the first songs of Tears For Fears – ‘Suffer The Children’, ‘Pale Shelter’ and ‘Watch Me Bleed’ – gave me hope that I could get hits with this synth band. I liked both of the boys a lot. Roland was a little moody and reserved, but sharp as a tack, with great humour, while Curt was the affable chappie who was really interested in his career and how to succeed.

RO: I think the advance was about £12,000, which for us was, like, "Woah!" It might have been £14,000, but it was a two single deal.

CS: The record company didn’t think we should call ourselves Tears For Fears because they’d had The Teardrop Explodes, but we were pretty adamant. And my argument back then was it’s like arguing with The Beatles about their name. I mean, what a lame name! But once the music’s out, who gives a shit? Led Zeppelin, you know? These things become iconic once you make music.

DB: I’d tried very hard to sign Depeche Mode, offered them a big deal, but was rebuffed. Depeche were very pop orientated; Soft Cell was an odd mixture of pop and a dark suggestion. Ultravox, Visage and Spandau Ballet were the New Romantics and were already established and successful. Tears were more of an intellectual, moody proposition. I was allowed to sign them on a two single deal, with an option for an album, which means I had to succeed in the charts with the singles before being allowed to carry on and make an album. I released ‘Suffer The Children’, and John Peel picked up on it and compared them to Joy Division. The NME reviewed it and likened them to Joy Division as well.

RO: I think Joy Division and Echo And The Bunnymen, the bands that wore black, allowed the sort of ‘Woe Is Me’ bleak songs that we were doing. We had a New Romantic spin in terms of that was the way to have the hair at the time – asymmetric, or plaits or whatever – but we weren’t anything like Duran Duran. You’d see them on a yacht and it was all about excess and glamour. We weren’t about that. It was all about an interior world, and not about the exterior world.

DB: They were never a Joy Divison. Miles from it.

CS: Obviously we had a dark side, and back then I got the comparisons to Joy Division and New Order, but we’d never really seen ourselves as a genre [act], the reason being both of us are incredibly unconscious of fashion. When there’s a genre of music there’s a fashion that goes with it, normally, and I don’t think we fit into that because we were from Bath and most of the genres were city based. They were Manchester, or they were London. We were from a small town, so I don’t think we ever felt like we fitted in with anything particularly.

RO: The thing that set us out from the crowd, I think, was that we were quite happy to take on slightly more semi-intellectual concepts, you know, and try and turn them into hits. We were young, weren’t we? And relatively handsome! In chunky knitwear!

CS: I think there were so many influences around at that point. Gary Numan, for one. Peter Gabriel’s third album… The Talking Heads record [Remain In Light], and [David Bowie’s] Scary Monsters. All amazingly produced records. And so we were very aware that we wanted to get into production. And Peter’s third album was probably the biggest influence on the recording, if you’re going to name one. It’s quite obvious in ‘The Prisoner’. I actually love that song. It brings that depth to the album. I think that without ‘Ideas As Opiates’ and ‘The Prisoner’ it doesn’t have the same depth.

RO: [The first single] ‘Suffer The Children’, was played for about six weeks on Peter Powell alone.

DB: There was some enthusiasm, but not enough to get going. They were not a live act, so nobody could "discover" them. Their lyrics were deep, maybe even dark. They had meaning, not the usual pop fare. So single number one went down. Then ‘Pale Shelter’ came out. Again little nibbles, but no bite. So I tried using Mike Howlett, who’d produced Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark.

RO: We did about four tracks. It was not going the way Curt and I had intended, so we alerted Dave Bates and that was stopped. We then had a meeting in Bath with Chris Hughes. We knew him from an album by a band called Dalek I Love You.

DB: I had been involved with Dalek I Love You, who were an influential band to British synthesiser acts. They were from Liverpool and originally featured Andy McCluskey, who went on to form Orchestral Manoeuvres, Dave Balfe, who was in Teardrop Explodes, Budgie, who became the drummer for Siouxsie and the Banshees, Dave Hughes, who also was in Orchestral Manoeuvres, and Alan Gill, who went on to join the Teardrop Explodes as well. I loved synth music and artists, and for some inexplicable reason Dalek I never made it.

Chris Hughes (CH): One day in early 1982 I was at the Phonogram Records building – Park Street, London, in those days – walking past my good friend and long time collaborator David Bates’ office. He shouts, "Come have a word with this guy on the phone." I spoke to an articulate, quietly spoken gentleman, who was concerned about some recordings he had made.

RO: We did ‘Mad World’ with him and Ross (Cullum, engineer). It was just brilliant. Had it continued like that it would have been amazing! The recording of ‘Mad World’ is so warm, so atmospheric. I’d made the demo pretty much on my own. The way that Chris augmented it is fantastic. It’s a very earthy sounding record.

CH: We did it at Brit Row Studios in London. Roland had a vision of how the song should sound and feel, and they both had a strong sense of what they wanted. The small team of Orzabal, Smith, Hughes and Cullum set about quickly re-recording an already well defined ‘demo’ and turning it into the track we all know.

RO: It did start out as a B-side because it was a song that I wasn’t totally enamoured with. I’d tried singing it. We needed a B-side to ‘Pale Shelter’. I took it in to play to Dave Bates and he said, "No. That’s way too good for a b-side. You’ve got to keep it." I said, "OK, sure." And it was really Dave that said, "No, that’s the next single."

CS: We argued about that the same way we argued with the American company about releasing ‘Everybody Wants To Rule The World’. We’re not A&R people! We didn’t expect ‘Mad World’ to be a hit.

RO: We thought ‘Suffer The Children’, ‘Pale Shelter’ maybe…

CS: Us and Dave actually believed that it was the coolest sounding thing on the album because it was very, very different. But it’s pretty dark. The reason we released it was that we felt it would give us credibility. I always thought it would just take time. I honestly felt the quality was there. It was just a question of finding the right breakthrough. There were times of concern after we’d released two singles and neither was a success. Polygram had signed us for just two singles initially, and those were ‘Suffer The Children’ and ‘Pale Shelter’. But Dave had a belief in us. We had a belief in ourselves. Chris Hughes was then on board as a producer. And we thought we were an album band, not a singles band. Especially with The Hurting.

RO: It’s a concept album. Tears For Fears was a concept. The Hurting is a concept album.

CS: Let’s face it, it was!

RO: And then that concept got watered down and watered down…

CS: So Dave convinced [the label] to let us make the album, and the third single – the first one from The Hurting sessions to be released – was ‘Mad World’.

DB: If I was going down, I was going down having done everything I could to make this successful. I wanted to make a video for it. In the recording studio Roland used to do this dance when he was enjoying himself. I had never seen anyone dance this way: odd, weird, unique. Perfect for the video, some odd plot of being able to see the world from a different view through a window. He did this dance of his in the video, which became very eye-catching.

CS: It was nothing peculiar to me. This is what Roland does in the studio: he’s constantly doing weird dance moves. And we thought, "Why not put it in the video as well, because it’s interesting?" I was certainly not embarrassed by it, put it that way.

DB: Slowly but surely the record took off on radio. The video was getting used too. Then it took on a life of its own.

CS: It ended up giving us a big hit.

DB: ‘Mad World’ went to number three.

CS: And the rest is history…

RO: I couldn’t believe it! It just kept going up the charts in those days where records didn’t just go in at number one and fall. It was quite remarkable! It was a muted excitement because we were still making The Hurting, but every week Music Week would come out: "Oh yeah, you’ve gone up ten places." Just incredible! Who knew?! It’s bizarre!

DB: Let’s take a simple view: a hit song has to have a catchy chorus, something anyone and everyone can hum, whistle or sing while at work, driving or walking. ‘Mad World’ had that. A vocal that is unique, stands out and is easily identified? ‘Mad World’ had that. Then a production or sound that has something uniquely identifiable that stands out? ‘Mad World’ had that. From the first time I heard it, I believed that it was a hit.

CS: The subject matter seemed to click with people. How simple it was, and how dark it was, seemed to connect. It says something about the English psyche, that’s for sure, as did the Gary Jules version being a number one hit at Christmas. That’s hardly the subject matter one would consider for a Christmas hit! And ours got to number three over the Christmas period as well. Maybe English people get depressed over Christmas…

RO: That song, God bless it, has done so well, with other people covering it as well. When I heard the Gary Jules version, I was just gobsmacked. I thought, "Woah, blimey! Well done! Well done, 19-year-old self, you!" It’s just one of those records. I think it was the sound which was bang on. At the time it was progressive electronic music. There were barely any guitars. It had that slight heavy beat to it, and I think it’s probably the best vocals Curt’s ever done.

CS: Obviously there’s stuff I’ve done on my own that I think is better, only because they have more meaning to me in the sense that I wrote the songs. But yeah: I think it’s one of the best ones I’ve done.

RO: I was very particular abut the songs I wanted to sing, and if I could use my voice.

CS: Normally it’s pretty obvious. If it’s a softer song it’s normally me. If it requires being belted, it’s normally Roland. My voice is a lot darker, a lot more melancholic, and Roland is more of a shouter. He’s trying to make a point. Which is very loud. So those are the differences in our voices, basically. ‘Mad World’ and ‘Pale Shelter’ and ‘Change’, even though they’re pop songs, wanted to be more melancholic and softer, and that’s my voice. ‘Mad World’ seemed to come pretty naturally, and it was the beginning of our relationship with Chris and Ross Cullum. They brought a lot to the process, and we were really enjoying working with people who knew what they were doing. And also it’s a very simple song, and we wanted to make it sound different, and the only way to treat the song was in the production, and we agreed on all the production on that track. So in that sense it was enjoyable.

RO: Most of the songs were written in the flat that I shared with Caroline, who’s my wife now of thirty years. It’s above a pizza restaurant now. I don’t know if it was a pizza place then, but it’s bang in the centre of Bath, and me being unemployed, and without anything really to do or to get up for, I used to sit at the window and just watch people go about their work. It was simple as that. Writing those songs was therapeutic, definitely. The recording of the album, not so.

CS: It definitely got harder after [‘Mad World’]. We didn’t want to make just a commercial album. We wanted to make a statement. I think we were quite pretentious. That was the age we were at. We were convinced that we were right in everything we did. Show me a 20-year-old college student or university student who’s not pretentious. That’s what you are at that age. You think you know everything. It’s not ‘til later on in life you realise you don’t. And that was all part and parcel of what we did. We were not a one-dimensional band. Songs like ‘Ideas As Opiates’ and ‘The Prisoner’ were definitely the side that, in a weird way, during the recording became more important to get across.

RO: I would never really choose to record like that again. The Hurting was painfully slow.

CH: I’m not sure that it was weak decision making on anyone’s part, more a sense of, "This isn’t good enough, perhaps we could try this instead…"

RO: It was just the four of us who were responsible for it: myself, Curt, Chris Hughes and Ross Cullum. And we were living in London. Our homes were Bath.

CS: We were locked away in this penthouse studio in Abbey Road, cut away from everything, for nearly a year. I think it took its toll. The hours were long, and it was back then when we were young. In later years in life you learn that anything you do after midnight is worthless because you’re just too tired. You think something’s good and then you come back in the next day and you realise it was dreadful. And there was the pressure from the record company. We realised we had something with ‘Mad World’, and we needed more than one hit from an album. I guess being tugged in every direction did make it hard. Plus then we got management, so there’s another voice in your ear. It’s the pressure of the business, the side that myself and Roland have never enjoyed that much.

CH: There was pressure there. There were late nights, but there were tracks we were making that were extremely well received. I had no interest in rushing and not giving due care and attention to things. We weren’t trying to capture a first take punk outburst.

CS: We were learning along the way. The band we had before, Graduate, was very much a live band, and when we recorded we just went in the studio and played live. It wasn’t layering and producing. This was us learning how to layer and produce, and trying to find our own voice with other people around us pulling us in different directions. So the process of learning in that scenario made it kind of difficult.

DB: There was demand for the next single to be lined up. But it would mean more interruptions to the recording process, with interviews, video shoot, artwork et cetera to be done for it in advance and during the release. ‘Change’ was perfect as a follow up.

RO: Here’s another piece of trivia for you. I wrote ‘Change’ for my wife to sing. We made a demo. And Curt heard it and said, "That’s a good song." I said, "Really?"

DB: The stress was because we had a single taking off, TV shows to do, radio sessions, press, photo shoots, more interviews. Each single took three months to line up with artwork, manufacturing, video, advertising campaign, long lead magazines et cetera. The recording was going slow because the people involved were perfectionists. They were taking demos and making them better with more ideas going into them. Writing songs in the studio is never a good idea.

CS: To be honest, [The Hurting] was kind of an uphill struggle. Because it wasn’t your average pop record: myself and Roland spent a lot of time trying to make it an artistic record, even though it definitely had melodic tunes on it. We wanted the album to have some meaning, and a lot of the time that goes counter to the way record companies think. So at times it was an uphill battle, but gratifying when it became successful, because we realised you could do both: you could be artistic and successful.

RO: We weren’t particularly liked by some of the music journals. If you were on the front cover of Smash Hits, you were doomed. You’re not going to get a good review in NME. No way.

DB: Initially [the media] thought they may have a Joy Division on their hands. When they couldn’t see them play live or connect to them, they turned their backs on them. I think you’ll find that it happened to Depeche Mode too, as well as Ultravox and the Eurythmics. Probably any band that used a synth didn’t have great press. The press in the UK were in love with The Smiths, as well as Echo & The Bunnymen, Sonic Youth, and New Order. As time went on things changed. It took years for Depeche to be acknowledged. By then they were huge in America. Mind you, so too were Tears For Fears.

CS: People never understood or got to grips with Tears For Fears, because it’s not the norm. I think the fact that people have never been able to put us in a musical genre or a musical bag has been confusing.

RO: I think we were cool for five minutes until we went on Top Of The Pops, really. John Peel was playing us – we did sessions for John Peel when nobody had really seen us – but then if you’re signed to a major label, two young pretty boys, they’re going to push you into doing the poster pop as well, and at that point you’re going to lose a lot of people.

CS: But at the age of 21 we were going off to countries we’d never been to before, so it was kind of exciting as well for us. It was very tiring, there was little spare time, but we were young and we were seeing new places, and so there’s a certain excitement about that. I did find the screaming girls a bit peculiar. That’s just the way we were. We were undoubtedly awkward. It was peculiar for people like us to experience people trying to rip your clothing off.

In England it was a big number one record. It went straight to number one as soon as it came out. It was sort of a big cult hit in America. We’ve had people like MGMT coming to shows in Detroit, Foster The People when we were in Korea, younger bands that really cite The Hurting as a big influence. And you meet other people, like Billy Corgan or Gwen Stefani, who are beside themselves because they were such big fans when they were younger. You might say it’s juvenile, or depression, or angst, but it seems that a lot of people go through that phase. And it stretches across the age spectrum, which is interesting. And genres as well. I mean, Swiss Beatz is a big fan. Hardcore rap groups like Gangstarr. Kanye West sampled ‘Memories Fade’ on his album. He hadn’t sought permission for it. One side of you is pissed because he thinks it’s his song because he changed the lyric. He kept the melody, he sampled the track. That’s Kanye West for you! But the people that cite us as influences or sample our tracks, it’s a compliment. I prefer to take it that way.

RO: The Hurting was one thing: pure Janov.

CS: What changed that for me was actually meeting Arthur Janov.

RO: We broke it really big with Songs From The Big Chair, both in England and America, and then he became hyper-aware of who we were. So we were doing four nights at Hammersmith Odeon, and he came to one of them. We met in the dressing room afterwards. I spoke to him a couple of times on the phone, and we all met up for lunch – me, Curt and our partners – in some fancy restaurant in Chelsea.

CS: He proceeded to ask us whether we might be interested in writing a musical about primal theory. At that point I lost the plot.

RO: It was one of those situations.

CS: Basically it was as if God had come down and said that he wanted you to find ways to make him money. It would be like God taking sponsorship.

RO: The words to the musical were just literally…

CS: I don’t think lyrics were his strong point! You know, there are some words you don’t put in songs, and long psychological explanations are really not things that songs are written about! I was destroyed after meeting Arthur Janov.

RO: I ended up doing primal therapy after Big Chair and during Seeds Of Love, and then I realised so much of you is your character, and you’re born like it. I think that definitely any trauma – whether it’s childhood or later in life – affects you negatively, especially when it’s suppressed, but there’s so much of us which is already in place. I believe that primal theory – which has been absorbed into modern psychotherapy practices – is very, very valid, but a good therapist is a good therapist. He doesn’t have to be a primal therapist.

CS: When he actually came to the show, I was talking to him for a while, and he said "I don’t think you need therapy", which was fantastic for me to hear. After that lunch, I didn’t feel like it anymore.

A deluxe edition of The Hurting will be released by Universal on October 21. A small number of quotes in this story were previously used in Classic Pop (Issue 6)