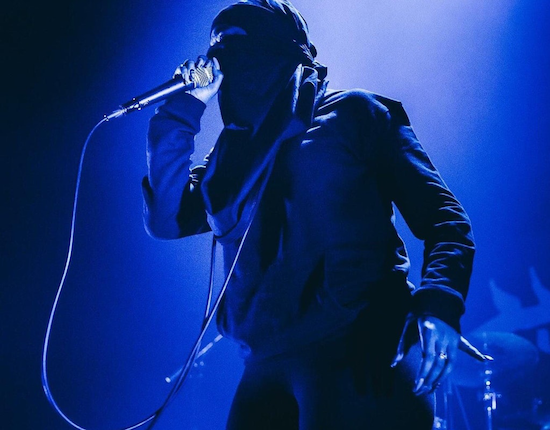

Taqbir live in Utrecht, courtesy of Le Guess Who? festival

Taqbir are a post punk band who encourage and empower North African women to be themselves. Growing up in Morocco, pursuing the simple pleasures of freedom of self-expression – especially through the production of non-censored music – could cost you your life. Historically, rock music and the metal scene haven’t been particularly welcomed in Morocco, but the two main cities of Rabat and Casablanca have seen something of a DIY underground begin to emerge in the 21st century. In 2005 a ska-infused punk band called Zlak Wlla Moute (Z.W.M) formed in Rabat and introduced some of the more modern ideologies of punk into the region. Between this and heavier music making its mark in Casablanca, it’s fair to say that this music exists in Morocco; it’s just that it tends to be an ultra-outsider concern given the life-threatening consequences that can flow from performing it.

As members of a society that teaches women to stay silent, obedient, and essentially powerless, Taqbir use their music to create a space for people like themselves to freely express their anger. Working against a culture that deems their music and outspokenness an insult to the national religion, Taqbir have carved out a space as a punk band of colour whose voices and images are something their younger selves so desperately needed as an inspiration and a statement of hope.

Victory Belongs To Those Who Fight For A Right Cause is Taqbir’s first body of work and finds them pumping annihilating riffs and angry spoken word with penetrative, fuzzy basslines. By pushing their anger towards the sexism, homophobia and racism that lingers like a dark, poisonous fog around Moroccan culture, Taqbir play a very dangerous game. They are putting themselves on the frontline, risking potential imprisonment, death threats and more, just to escape the cultural prison they’ve grown up in.

During lockdown, Taqbir grew from a duo to a full-force five-piece examining the punk music scene through a riot grrrl lens. For fans of female pioneers essential to the emergence of the UK punk scene such as X-Ray Spex, Bona Rays or The Slits, their music may occasionally feel familiar but Taqbir are essential in 2022 in that they use their voice as an act of rebellion against a young lifetime of oppressive systems.

In 2021, Lardux Films dropped a short documentary called Dima Punk (Once A Punk…) highlighting the scattered and underground punk scenes of Morocco through the life of acclaimed punk, Mostafa Dit Stof. Stof has seen friends both imprisoned and killed for their commitment to the music they loved and is a prime example of the need for keen survival instincts in a subculture constantly threatened with erasure by society at large. By working in the same musical and political environment, Taqbir are under threat with every project they work on, and every inch of press that surrounds them.

Also shunned by their biological families, they are punished in other cruel ways for their bravery, but in the face of this Taqbir are a band desperate to build a new family or place of refuge for those who don’t fit in. Signed to London-based independent record label La Vida Es Un Mus Discos, Taqbir are part of a roster of idiosyncratic underground punk bands who all have a taste for rebellion in common. Understandably, with all the above in mind, Taqbir’s members don’t use their names publicly: for the purposes of this interview, they asked that their spokesperson be referred to as Aicha.

To me, the music that Taqbir creates is a political escape and a righteous passage to freedom. How would you describe your music and ethos?

Aicha: Taqbir is freedom. We’re a band who want to support everybody’s choice, we’re against established rules. Taqbir is about breaking the rules!

What is it about the patriarchy that sparks anger within Taqbir’s music?

A: I think that as a woman I have been oppressed by two patriarchal systems. The first one is the systematically patriarchal system, and then there is the religious side. For me Taqbir is against all types of patriarchy, but the religious one is our main oppression since we have always lived in a religious society.

Do you feel that religious patriarchy is more restrictive than political?

A: [In Europe] you have the hyper-sexualisation of women. Being raised in a Muslim community, it’s completely the opposite – as they tell you to be modest. I live in the west now, and I’ve noticed the women are oppressed by being hyper-sexualised. Whereas in my society, it’s the opposite, we don’t have the chance to sexualise ourselves, we don’t have the freedom to. We are taught to cover up, and this is really hard – people like to express themselves with their hair, make-up and clothes. So being forced to be a certain type of woman and to not have your own identity, it’s very hard.

Do you think this has been a good motivator? Having not been able to explore your identity through these basic pleasures, do you think that through your music you have a space to explore your freedom?

A: Yeah definitely, especially because the punk scene is so expressive. It’s very important to me to raise my voice, and to be able to have the choice to dress the way I want to was one of the first things I thought about when I started to rebel against religion. When I was around 12 or 13 I started to listen to punk music, I wanted their aesthetic, I wanted to look like the girls I saw on the internet. My country wouldn’t allow me to express myself in that way, and that was the moment I said that if I could not dress how I wanted, then this wasn’t my [home].

Other than your anger against the patriarchy, what other message would you like to convey through your music?

A: That we don’t give a shit. I spent most of my life under rules, so for me the first message of Taqbir is to break the rules and be yourself. So many people don’t like us because it doesn’t match with their politically correct ideologies. Because we have a message to convey about how we oppose the way people are discriminated inside of these communities and religions.

The title of your EP is Victory Belongs To Those Who Fight For A Right Cause – can you give me an example of a cause that is close to you that you fight for?

A: I think, because I have my own political ideologies, as a woman who belongs to the working class, I believe that the anti-capitalist, anti-system movements are close to me. Being against a homophobic, racist society, the people who stand against injustice – victory belongs to them. Because they’re fighting against this criminal system, and I think anyone who is willing to fight this is a winner.

Has there been a moment across your career where you think Taqbir have had a political victory?

A: Yeah, when I talk about my story and everything I had to go through within my life, for me it’s a victory when people from my community have said things like, "Thanks to you I’m not alone." With Taqbir, we receive a lot of messages like this. For me that’s a victory because I felt alone for the most of my life, and to know there are people who can relate to our music is a victory.

Understandably, not every cause that you fight for is going to have a happy ending. Can you give an example of where this has happened?

A: Yes, with my family. I live without them, it’s not a happy ending, but it’s something that 90% of the women like me that have to do – to break up with their families, their religion, their community. In order to see victory, you have to be content with making some sacrifices. In every cause, there are sacrifices to be made, and for me it was this. If you lose your family, you can always gain a new one elsewhere. We’re never going to be alone in this world, you just need to search for this safe space. Because sometimes it isn’t our blood family, it’s our friends, and that’s okay.

How did you emotionally recover from the cycle of discovering who you are, to then essentially being shunned by your family, your culture and all that you’ve been brought up to believe?

A: For me, it’s really hard to recover from it, because the pain is always inside of you. You’re constantly asking yourself: why can’t they accept me? I’m being myself; I like punk music; I’m not killing people. It’s really hard to empathise with your family. It took me a long time to accept that my family grew up in a different time, with different values. They cannot understand my way of life, but I accept them for the way they are. I have asked not only my family but the people in my community to accept my choice, I don’t expect them to accept me as a I am but to be allowed to be left alone. You live your life and I live mine, hakuna matata.

And so essentially the thing here is, you don’t forget the pain, you just learn to live with it?

A: Definitely, there’s always an emotional nostalgia attached to it. Now I’m a grown-up woman, I have my own job, my friends, my life, but you always want to share your victories with your loved ones. You cannot do that, and so that’s the sad thing that you have to live with. I cannot go to my parents and say, "Hey I have a band, come and see me on stage." They can’t even see the work art.

It seems that even as a feminist punk group who have built these spaces and can rage with the loving circle of their fans and friends they’ve made along the way, there’s always going to be a void. It comes as a consequence of chasing the “dream” of complete freedom. For Taqbir, and many other people in their position, to wish for and successfully sustain freedom away from the suffocating captivity of systemic patriarchy and/or religious values is to walk away from everything you have ever grown to know about yourself. Your freedom is far from free, but is filled with a euphoria near enough impossible to describe.