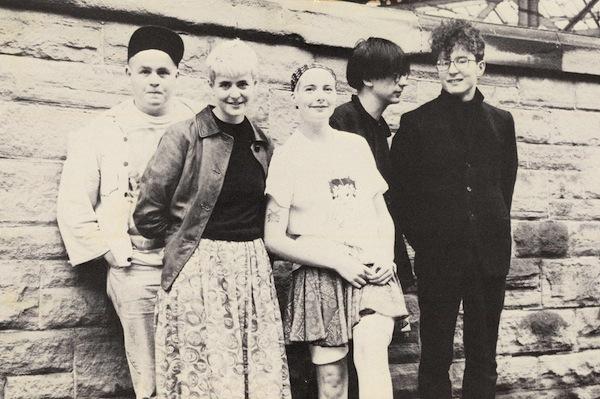

Amelia Fletcher stood close to signing a major label deal when the rug was pulled from beneath her feet. After her band Talulah Gosh decided to call it quits in 1988 and the four original members – Peter Momtchiloff, Robert Pursey, Amelia and her brother Matthew Fletcher – reformed under the name Heavenly, Island Records came knocking at their door.

“The A&R guy was told he could choose one band and he was interested in us,” recalls Fletcher. “Unfortunately, he shared a namesake with our cat. Jessie used to sit outside our rehearsal room and meow, so every time the label came to talk to us quite seriously, I – who probably wanted to be famous the most – would talk to them quite sensibly – but I could hear the rest of the band meowing in the background. I think looking back we probably did want to be really really famous but we were completely unwilling to do any of the right things to make it happen.”

For anyone familiar with Talulah Gosh, this schoolroom snapshot of a band so infantile they did everything they could to halt progress towards a serious rock & roll goal, makes perfect sense. A childish act of self-sabotage, it probably cost them their stab at commercial recognition, but that was never a priority anyway. And it ended up being rather fortuitous for the non-feline Jessie; he signed Pulp instead.

Taking their name from an NME interview with Clare Grogan, Talulah Gosh formed in Oxford on February 1986, the same year a little-known band called On A Friday played their first ever gig at the city’s Jericho Tavern. Andy Bell – who would go on to form Ride just two years later – came down to watch Talulah Gosh play. “I think he saw that you could be in a band who were successful when you really couldn’t play anything, and that was inspiring,” says Fletcher. “It was inspiring for women but also for men. It was a similar thing to punk and of course we were very into the whole DIY aesthetic; we made our own sleeves. We made our own clothes – to some extent. And we certainly didn’t have a press person in those days!”

It seems apt that they were among those featured in Jon Spira’s 2010/11 documentary about the Oxford music scene (named after a Radiohead song) Anyone Can Play Guitar. Not just by virtue of geography alone but because, as with punk a decade before, they prided themselves on their amateurishness. They couldn’t play their instruments, in the conventional sense but then that was kind of the whole point.

Talulah Gosh were not featured on C86, the mail-order cassette put together by the NME in 1986 which united a geographically diverse but largely like-minded raft of contemporaneous British guitar bands. However this seems like a bizarre omission seen from the vantage point of 2013, especially when the cassette included such square pegs in round holes as Age Of Chance. (They were included on Bob Stanley’s CD86, a compilation which celebrated the 20th anniversary of the seminal indie tape in 2006.) This so-called C86 scene is now viewed as a vital turning point for UK indie, one which championed the underground, further broke down the gender divide by welcoming the participation of more women as musicians and offering an alternative to rock & roll and punk machismo. It also later influenced the riot grrrl movement and, as with post punk, helped engrave a DIY ethic onto the cultural consciousness which has since shown few signs of fading away.

With Elizabeth Price – “Pebbles” – on vocals (replaced by Eithne Farry on tambourine and vocals in December 1986), Amelia Fletcher – “Marigold” – on vocals and guitar, Amelia’s brother Matthew Fletcher on drums, Rob Pursey on bass – later replaced by Chris Scott – and Peter Momtchiloff on guitar, Talulah Gosh went on to release a steady stream of 7”s. They took a refreshingly anti-macho stance. “The main thing was that we were very keen not to be sexy,” explains Fletcher. “We were absolutely trying to go diametrically the other way to anything like the Miley Cyruses of the time. There are occasional photos of the band with girls at the front but not that many – we would fight to have everyone evenly treated.”

One of their first singles, ‘I Told You So’, came out as a split flexi-disc with the Razorcuts and was presented with seminal indie fanzine Are You Scared To Get Happy? It coursed through the veins like an illicit sugar rush, all little girl vocals and playground fisticuffs. Other offerings such as ‘Steaming Train’, ‘Beatnik Boy’ and ‘Bringing Up Baby’ dealt in the currency of adolescent romance and wide-eyed wonder, galloping along at the breakneck speed of punk. But it was the band’s self-titled third single – a maudlin meditation on the brevity of fame, written by Amelia’s late brother Matthew – which earned them their indie stripes.

For noise-pop disciples, the band’s sonic path has since been well-trod. A triptych of musical scenes informed their sound; 60s girl groups, 70s garage-punk and Creation-era indie. Talulah Gosh also ingested a heavy dose of their beloved Pastels – Amelia Fletcher and Elizabeth Price were both wearing badges advertising their love for the Scottish indie band when they met.

Mud-slinging came from those opposed to the band’s overt ‘tweeness’. “I guess we did have a love of childish stuff and were deliberately non-macho but we never thought of the word ‘twee’ back then, and we still don’t now,” says Fletcher. “What was interesting was at that time bands like that The Pastels, for instance, twinned leather trousers with anoraks; it was that combination of seeing the world through a child’s eye but also having a darker, harsher side which we wanted to get across.”

Talulah Gosh were divisive from the outset but for their acolytes, the band’s amateurishness was their charm. “We caused controversy rather than courted it,” laughs Fletcher. “I guess we just didn’t really know what we were doing. Some people loved the fact that we could play four chords and we thought that was sufficient and other people – particularly those of the male variety – thought that was terrible.”

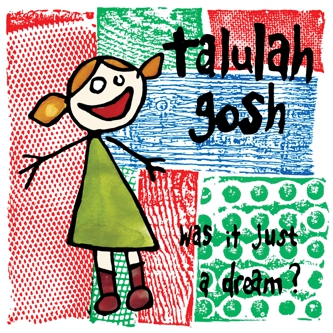

Following 1996’s hard-to-find Backwash compilation, Talulah Gosh have consolidated their life’s work into a recent 29-track retrospective, Was It Just A Dream? featuring radio sessions, four “kind-of-rarities” (original demo versions which they recorded in their bedroom), archive photography and liner notes by The Legend! aka Everett True. So how does Amelia think her brother – who sadly took his own life in 1996 – would have felt about the retrospective? “I think he would have been truly amazed that anyone was still interested. He would have been derogatory about it because he was usually derogatory about things. But he probably would have been secretly proud.”

Included in the retrospective is an open letter penned by Matthew entitled The Death of Talulah Gosh. “It was very witty. A couple of people who knew him said how strange it was seeing a letter in his handwriting but he and Alison (Wonderland, who did the artwork) were also good friends so it all adds up nicely.”

Ironically, it took two years to complete. So what was it like going back? “I think we’ve actually all been pleasantly surprised as we remembered it as being a bit terrible but actually, in retrospect, we can see why people may have liked us and why they were interested. Some of the tracks are recorded really nicely and I definitely don’t remember that happening!”

Named after one of their songs ‘Just A Dream’, Amelia says that they initially had different plans for the title. “We wanted to call it Grrr – the shortening of grrrl – which we felt was very appropriate because even though we were way earlier than riot grrrl, there’s still a bit of a lineage. But then the Stones put out their album just as we were finalising everything so we had to change it!”

Acquiring the photo rights was the lengthiest part of the process, as was nailing the sleeve, designed by long-time friend Alison Wonderland but with the picture taken from an original flyer drawn by Amelia at the time. Having penned the band’s typically poetic, unashamedly gushing liner notes, Fletcher says the Everett True connection runs deep. “We really owe our career to him: “I read his Legend! fanzine before I’d even had a band and loved it. We went to loads of the same gigs in London and then when Talulah Gosh formed I think he came to our second or third show and he wrote a full pager in the NME about us; that what was basically got us started.”

In a few hours’ time, Fletcher will make the pilgrimage to her former homeland, Brixton, to DJ at the much-loved indie-pop institution that is How Does It Feel To Be Loved?; a club night which shuns britpop and shoegaze in favour of the fey and bittersweet, making for a readymade school disco vibe which is readily swallowed up by its followers. She’s spun the decks there before but tonight holds particular significance for both Fletcher and in the genesis of the club. “I DJ’d the first ever HDIF ten years ago and it went pretty badly. We lived literally across the road at the time, which is why I was asked, but I’d just had my first daughter. She was about four or five months old and I thought I would be fine to go off and DJ. But I basically played about five songs before someone came across from home and told me she was screaming and I was needed.”

Elizabeth Price went on to win the 2012 Turner Prize, Peter Momchiloff is philosophy editor at Oxford University Press, Amelia Fletcher is a Professor at the University of East Anglia, Eithne Farry is books editor at Marie Claire and an author of lo-fi craft books, Rob Pursey is a TV producer, and Chris Scott is travel counsellor. Fletcher, 46, completed a D.Phil in economics at Oxford and joined the Office of Fair Trading where she became chief economist and director of mergers. Although she admits to having experienced hunger pangs of fame, she always knew that the music would play second fiddle to her degree and later, her professional career.

“I think we needed to treat it more like a job and not just a fun diversion but, actually, that’s a great thing because now that’s how it will always be remembered.” And three decades on, Talulah Gosh’s indie-pop legacy burns brightly.

Was It Just A Dream?

For those of us that care, the now moribund festive period has been coloured in part by a sense of muted, slightly dubious celebration: the announcement of an ‘amnesty’ by the Russian Duma in the end days of December 2013 meant that the two remaining incarcerated members of punk band Pussy Riot – Maria Alyokhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova (having already served the best part of a two-year sentence for ‘hooliganism’ under what appear to be notably punitive conditions) – have now been released.

Since forming in 2011, Pussy Riot have staged a series of elegant, scathing, and – undeniably – funny-as-fuck artistic protests against Putin’s increasingly repressive and shady regime; protests which eventually led to their arrest, a surreal & draconian trial and imprisonment, amidst much international attention and outcry. They did this in part by way of an erudite and instinctive reinterpretation of a Westernised punk rock aesthetic; overtly acknowledging the punk, Oi!, and riot grrrl movements as significant cultural influences which actively inform their praxis.

1980s Oxford, UK band Talulah Gosh have recently released Was It Just A Dream?; one of those beasts we clunkily term a ‘career retrospective’, which, like 1996’s collection Backwash, pulls together all of the band’s extant releases, but with the addition of a few live, demo, and session rarities, not to mention a sense of renewed pertinence.

Revisiting these songs is a joy which forces a welcome reappraisal; Talulah Gosh are one of those fecundating bands who are increasingly feted for their influence on later music, or for the illustrious subsequent careers of their members (comprising authors, Turner Prize winners, indiepop legends, academics, TV producers, chief executives and – as of a week or so ago – an OBE). But Amelia Fletcher, Matthew Fletcher, Rob Pursey, Peter Momtchiloff, Elizabeth Price, and, later, Eithne Farry and Chris Scott, did something important in its own right during 1986-1988, and Was It Just A Dream? is a fitting, essential document of that.

I mention Pussy Riot in an article about Talulah Gosh not to suggest that these two bands sound anything like each other (they really don’t), or that they were involved in comparable political or musical endeavours (they really weren’t), but because there are, I think, in the punk rock aesthetics evinced by both bands, compelling and useful parallels to be drawn. Like Pussy Riot, who give themselves wickedly playful names like ‘Balaclava’ , ‘Blondie’, and ‘Cat’, members of Talulah Gosh adopted awkwardly cutesy monikers, including ‘Pebbles’ and ‘Marigold’.

Like Pussy Riot, who uniformly wear an array of brilliantly coloured, almost gaudy balaclavas, dresses and leggings, Talulah Gosh seemed naturally drawn to a distinctive sartorial flamboyance, a bright riot of flowery skirts, hairslides, hand-painted guitars, and tambourines. Like Pussy Riot, Talulah Gosh understood the power of ridiculousness, and mined it for artistic effect. ‘Adults dressed as children’ it may well be, but implicit in both bands’ embracement of the colourful, the amateur, and the brash, is a hyper-smart sensibility which makes them truly interesting, truly subversive, truly punk rock.

Of course, Talulah Gosh are often heralded (and occasionally lambasted) for being the standard-bearers of ‘twee’; a strand of indiepop which in its latter-day incarnations has often been called out for being cloyingly infantile, affected, and, I think, ultimately disingenuous in some indefinable yet fundamental way. Listening back to Was It Just A Dream?, I am reminded why such accusations have never been and can never be persuasively levelled at Talulah Gosh themselves; here are a band who, whilst being in many ways the archetype of twee, embodied that twee-ness in real punk rock fashion, with full understanding of its subversive capacities. Yes, they were twee as fuck. But the fuck was very much in evidence.

You can hear it best when you listen to the songs on this compilation back-to-back because apart from those gloriously melodic, harmony-laden, outrageously pop-soaked tracks still played by certain types of kids in certain types of clubs (‘Bringing Up Baby’, ‘I Can’t Get No Satisfaction (Thank God)’, and ‘Talulah Gosh’, of course), we also get reacquainted with the weirder, more tangential stuff. There is the sheer strangeness of ‘Sunny Inside’, with its tumbling lyrical delivery and frenetic, ludicrous shifts in tempo which make it sound almost like a dare. There is the riotous, cacophonous scream-a-long of ‘Testcard Girl’. There is the Ramones-romp through ‘Break Your Face’ and the elegiac surge of Momtchiloff’s ‘Escalator over the Hill’, a song which, with a titular nod to the obscure epic jazz opera of the same name, serves to calibrate the exceptional range and reach of this uncontainable band. In this track Talulah Gosh demonstrated that they understood – and could articulate in songs of understated beauty like this one – the enduring romance and emotional mileage of public transport; trains, buses, and, yes, escalators. More than this, effectively illuming the link between transit and the transience in our personal relationships (‘you can’t go back, I’m sorry’), ‘Escalator over the Hill’ demonstrates perfectly Talulah Gosh’s capacity to shuttle between achingly brittle, breathy, loss-drenched balladry, and their own vaguely schizoid, scuzzy, and shouty reinterpretation of punk rock.

The distances between the songs hint at something irrepressible and unafraid at the core of this band; they were so evidently complete audiophiles, so evidently busting at the seams with emotions and irritations, and so evidently going to try and make those things sound like what they thought they should sound like, even if they didn’t know how as yet. As Farry described it: "It was a collision of ideas… we were mixed up and muddled. I liked the idea of the possibility of being really awful." Attention to the reach of the music, contextualised with utterances like these, serves to strip away assumptions of Talulah Gosh’s artifice or affectation – these were young people as equally in love with sixties femme-pop as they were with seventies new wave or eighties jangly or shoegazey indie, and yes, you were gonna know the measure of that love.

"The idea of the possibility" – concepts such as these are brought back to us on Was It Just A Dream? via Everett True’s gloriously cut-and-pasted liner notes, in which the author documents his long relationship with, and love for, the band, amid numerous excerpts from interviews and lyric sheets. Perusal of this ephemera underscores the inference that Talulah Gosh knew exactly what they were doing, and just where the cyanide lay in the saccharine.

They knew about punk alienation: "The scary thing was seeing people looking really sweet and amiable… singing along to your songs you’d written in two minutes. You wanted to disown them." They knew how to subvert their own stances: “Amelia started talking about how, when she saw male singers on stage, she wanted to lick their bodies." They knew how to harness and have fun with the inherent creepiness of twee: "We care for small rabbits. But we don’t, because I hate pets! They die, and then you have to work out what to do with their bodies." They seemed to know that fun and insubordination often go hand-in-hand.

A lot of Pussy Riot’s power is the power of laughter; laughter at the sombre officiousness of the political and religious orthodoxies they directly provoke, who are apparently deeply threatened by the sight of a bunch of young women dancing and singing along to their own pre-recorded music, dressed in bright neon jumpsuits and balaclavas atop of a grey plinth in a public square of a Russian city one freezing winter’s day. Laughter at the crazy intersections of pop culture and politics. Laughter too at themselves, because they know that with a bit of intelligence, you can use a sense of your own absurdity to expose and challenge the more pernicious absurdities which lie immanent in those ideological structures which curtail your lives.

Talulah Gosh made music which derived its power from laughter, too, but also from a near-ineffable quality of unrestraint; there is such a revelling in the audacious, scrappy harmonies and ba-ba-ba-bahs of ‘Steaming Train’, for example, that it constitutes a kind of informed abandon, in which neither you nor they know where exactly they might go with this, only that – instinctively – it will be somewhere worth visiting.

It is no surprise that it is possible to draw a line of sorts between Talulah Gosh and Pussy Riot, via the former’s inextricable relationship with an emergent riot grrrl, and the latter’s with its legacy. Pussy Riot’s Tolokonnikova, whilst stressing the things which separated her band from those involved with Westernised riot grrrl, nonetheless suggested that "what we have in common is impudence". Whether accurate or not, the translated word is pleasing and particularly apt. It is slightly quaint, slightly off, hugely perfect. Both bands knew/know how to be trouble, in the most intelligent, defiantly sophisticated sense and both bands, in very different ways, succeeded in troubling the right things.

Since her release, Alyokhina has – with the marked eloquence we have come to expect of these dignified women – clarified Pussy Riot’s stance even further: "We really are provocateurs but there’s no need to say that word like it’s a swear word. Art is always provocation."

Provocatively, they say now (only a few days out of prison) that they are starting a new human rights organisation, which has nothing to do with Pussy Riot, and which will, ultimately, unseat Putin and his cronies: I love this, I love them for their lack of sentimentality about their band, and for their industry and balls, and I wish them all the luck and steel in the world.

And there are connections to be made, however tenuous they are, between brilliant and stupid bands in different decades and on different continents, because of the weirdly consonant things they make you think possible. On one level it seems ridiculous – ludicrous, even – to compare the driven political aspirations of a fringe proto-punk art collective from Putin’s Russia of 2013, with the dorky yet unsettled and unsettling agit-pop of a 1980s group from Oxford UK.

On another level it feels completely, instinctively right, and kinda a fundamental part of the reason why any of us care at all about making noise, or writing about the brilliant and weird people who do. Pussy Riot are certainly going to be worth remembering; and Talulah Gosh certainly are too. Sure, there are weird moments, awkward moments, ‘too-much’ moments amid the twenty-five tracks of Was It Just A Dream?; but then we all have those. Talulah Gosh were – are – an important, impudent, rare treat of a band, and the evidence is all here.