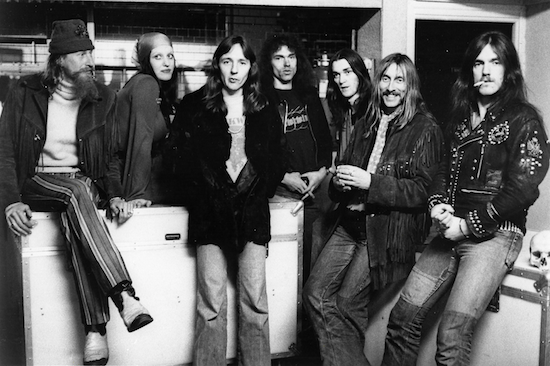

Hawkwind in 1975

Hawkwind were a one-band revolution in the 1970s. While the rest of the British rock scene was stuck in a dead end of pseudo-classicism and reheated versions of the recent past, Hawkwind tirelessly travelled the country to spread the good news of the counterculture – long after it had been declared dead by the supposed tastemakers of the media. They animated the provincial underground and became a rallying point for heads and freaks everywhere – just look at their classic Top Of The Pops performance of ‘Silver Machine’.

Aggressively flying in the face of music industry convention, Hawkwind valued raw energy over technical proficiency and displayed a bloody-minded desire to do things their own way, qualities that would be taken up by punk a few years later. The story of the band’s first decade reveals an alternative narrative for music in the 1970s. Figureheads of the free festival and avatars of the underground, it shows a band offering an active means of resistance to both mainstream music and society.

Hawkwind certainly were living in a strange world in the 1970s. If Britain in the 60s had been a time of increasing prosperity and optimism, the 70s was one of confusion and crisis. The post-war dream of social consensus and economic re-development had collided head-on with political inertia and industrial unrest, with the country permanently on the brink of chaos.

Hawkwind were a band made for these times. While most artists peddled rock & roll banalities or were too wrapped up in their own self-importance, Hawkwind connected with the world at ground level, producing a “black fucking nightmare” of noise (as Lemmy memorably put it) that reflected the turbulence of the age back at their audience, sonic attack as a form of self-defence against the bad vibes of straight society.

But even today, the strange world that Hawkwind themselves inhabit is a source of bemusement and confusion for many people. While the scope of their influence and innovation has been more widely acknowledged over recent years, they’re a band whose appeal often remains elusive beyond their still dedicated following. Yet in the 1970s, the division between fans and critics was positively confrontational, with the great majority of the music press literally unable to comprehend just why Hawkwind were so popular (and make no mistake, Hawkwind were a seriously big band in the first half of the ‘70s).

At the height of their artistic and commercial powers, Hawkwind channelled and amplified the era’s psychic tenor via a science fiction sensibility, mind-blowing visuals, and their unique brand of deep space psychedelia. What follows is a series of ten entry points drawn from their classic 1970s era that seeks to shed light on the various facets of Hawkwind’s world, and hopefully provide some sonic transcendence along the way…

‘You Shouldn’t Do That’ from In Search Of Space (1971)

Hawkwind were promoted as a ‘space rock’ band from the very start, but it was on their second album that they really achieved escape velocity, with this 15 minute opening track epitomising the classic Hawkwind sound: driving, minimal guitar riffs; propulsive, metronomic rhythm; raw, atmospheric electronics; and stoned, ritualistic vocals. There were plenty of serviceable freak outs on their debut album, but ‘You Shouldn’t Do That’ nails the electrifying combination of cosmic and apocalyptic that Hawkwind would make their own. Inspired by the endless, free-form improvisations that the band had famously performed outside the 1970 Isle Of Wight festival, it’s nevertheless held together by a surprisingly dynamic arrangement – unlike the West Coast jam bands that Hawkwind were inevitably compared with, this isn’t a rambling blues-based raga, but a hypnotic, linear rush. There really is no other band that sounds like this in Britain in 1971 (or any year, for that matter).

‘YSDT’ is also notable for the countercultural solidarity of its lyrics. Lines such as, “They put you down and cut your hair/ They’re saying you’re no good, they just don’t care” would have resonated strongly with their target audience. And as with many of their songs to come, the theme of escape from a repressive, paranoid reality is implicit throughout.

‘Brainstorm’ from Doremi Fasol Latido (1972)

For many fans, Hawkwind’s third album is the ultimate expression of their anarchic, drug-fuelled space rock. The band’s pharmacological intake at the time was a vital if somewhat nebulous component of their modus operandi – for instance, saxophonist and de facto frontman Nik Turner claims to have taken LSD every day for two years. But while Hawkwind always said they were essentially an acid and pot band, it’s the undeniable amphetamine edge that new boy Lemmy in particular brings to their music that gives it a speedy, proto-punk vibe.

Album opener ‘Brainstorm’ crashes straight into a body-pummelling, pulse-quickening ur-riff which channels both the unstoppable momentum and crushing inertia of interstellar travel. Yet as Turner trills, “I’m floating away”, his escape to the stars is clearly more drug-assisted than rocket-powered. It was the metropolitan psychedelic scene of the late 60s that had first driven an inquisitive elite’s experimentation with various illegal substances, but by 1972, recreational drugs were readily available in just about every town in Britain. Hawkwind re-invented psychedelia for a harsher age and took the underground overground, regularly touring their brain-blasting, synapse-frazzling live show around the country as the accompaniment to a million provincial trips.

‘Born To Go’ from Space Ritual (1973)

Space Ritual might just be the greatest live album ever released, and its version of ‘Born To Go’ could well be the single most exciting piece of music that Hawkwind committed to vinyl. From the moment its brutal, cyclical riff pounds the air, ‘Born To Go’ is an utterly thrilling exercise in both relentless forward motion and the abstract power of noise. Unlike the increasingly precious and mannered performances of their peers on the prog and hard rock circuits, Hawkwind accepted noise as an aesthetic in itself and understood its mood-altering properties, using it to engulf the listener’s conscious mind and short-circuit cognitive processes. Just listen here to Dave Brock’s sky-scouring wah-wah assault, the violent washes of white noise from electronics crew DikMik and Del Dettmar, the swirling debris of Turner’s disembodied flute…

But there’s something deeper here too. Unlike other ‘heavy’ bands, Hawkwind didn’t employ squealing feedback or strutting power chords. Compare, for instance, the riff to ‘Smoke On The Water’ with the one that drives ‘Born To Go’ – while Deep Purple’s is full of tension and sonic machismo, the Hawkwind riff is propulsive and fluid, a circular chord pattern that sublimates identity rather than affirms it. Rock culture might have been giving in to its lusty id, but here was a stronghold of the underground still intent on dissolving its ego.

‘Sonic Attack’ from Space Ritual (1973)

If Hawkwind were just a musical battering ram forcibly breaking down the doors of perception, that would have been impressive enough. But another core element of the band’s unique personality was the renegade intellectualism at its heart. For the most part, this came from visionary poet and conceptualist Robert Calvert, a friend of Turner’s who ricocheted into the band’s circle in 1971. An intensely compelling performer and an endless source of sci-fi informed ideas, Calvert began doing readings onstage and quickly came to regard Hawkwind as a canvas for his fervid imagination.

‘Sonic Attack’ is the most famous of his space age recitations, though it’s actually not one of his own poems. It was written by sci-fi and fantasy author Michael Moorcock, a key figure in the UK SF and literary scenes from the 60s onwards, and another Hawkwind ideas man. ‘Sonic Attack’ has become short-hand for the shock and awe of Hawkwind in full flight, but the track itself is all creeping dread and unease, a blackly comic take on public information films via the chilly logic of the Cold War. Its ending – Calvert urging “Do not panic! Think only of yourself!” over a throbbing machinic beat – is Hawkwind at their most terrifying.

‘The Psychedelic Warlords (Disappear In Smoke)’ from Hall Of The Mountain Grill (1974)

By 1974, that title might have been an open goal for those members of the press who had already written Hawkwind off as “Star Trek with long hair” (Lemmy again). But the lead track from their fourth studio LP was an early indication that, despite the oft-repeated complaint that “Hawkwind songs all sound the same”, the band were both willing and able to assimilate other styles of music into their sound. A sinister synth drone heralds an urgently chopped out riff that’s downright funky, before newly-recruited keyboards wizard Simon House adds some subtle orchestral colouring with the Mellotron, prog rock’s totemic instrument. And the skittering wah-wah, spare bass and phased cymbals of the extended outro could almost be a lost piece of classic rare groove.

With its opening lines of “Sick of politicians, harassment and laws/ All we do is get screwed up by other people’s flaws”, ‘The Psychedelic Warlords’ also flags the militant edge to many of Hawkwind’s songs (see also the previous year’s standalone single ‘Urban Guerilla’: “I’m society’s destructor/ I’m a petrol bomb constructor”). Yet while Hawkwind never claimed to be political, their commitment to playing innumerable benefit concerts made them visible standard bearers for the alternative society.

‘Opa-Loka’ from Warrior On The Edge Of Time (1975)

More acknowledged at the time than tends to be remembered, Hawkwind were identified early on by enlightened elements of the music press as being the closest thing that Britain had to the German avant rock scene, soon to become known as Krautrock. The band were friends with Can, had recruited Amon Düül II’s bass player, and Dave Brock had written the sleevenotes for the UK release of Neu!’s first album. They were for a time also pretty massive in West Germany. Given Krautrock’s subsequent influence on modern-day alternative music, it’s striking how little impact it seemed to have on British bands during its 70s heyday. Hawkwind really were in a genre of one in this respect.

Driven by the metronomic beat of double drummers Simon King and Alan Powell (later snarkily referred to by Lemmy as ‘the Drum Empire’), and with a pulsing, minimal bassline dominating the mix, ‘Opa-Loka’ is pure kinetic energy as art and the most obvious intersection between Hawkwind’s rhythmic aesthetic and Krautrock’s motorik ideal. Brock’s wah-wah is like a stone skipping through waves, while Mellotron and flute drift dreamily, and a synth burps electronic squiggles. The effect is totally hypnotic and could go on for days.

‘Steppenwolf’ from Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music (1976)

After releasing two solo albums – the wonderful Captain Lockheed And The Starfighters and the less successful Lucky Leif And The Longships – Robert Calvert was firmly back at the Hawkwind’s helm by 1976, and determined to move the band towards his concept of ‘spontaneous theatre’. Calvert regarded every song as a chance to externalise the films playing in his head, with his lyrics becoming increasingly narrative-driven. ‘Steppenwolf’ is a prime example, its title and inspiration coming from Hermann Hesse’s 1927 novel about man’s battle to reconcile savagery and civilisation. It brims with Calvert’s delight at the poetry of words and the mechanics of rhyme as he muses on his protagonist’s dual nature.

With its lush, midnight-hour looseness, the music of ‘Steppenwolf’ is entirely at the service of Calvert’s elegant tale-spinning. As a life-long manic depressive, this was the first of a series of songs that acted as metaphors for his yo-yoing mental health. When ‘Steppenwolf’ was played live, Calvert would appear in a frock coat and top hat, with walking cane in hand, and a severed head under his arm. The increasing physicality of his performances suggested that Calvert was acting something out that went beyond mere showmanship. He certainly wasn’t the first frontman to channel private demons on the public stage, but the way he allowed his characters and obsessions to take over meant he was sometimes a danger to both himself and those around him.

‘Damnation Alley’ from Quark, Strangeness And Charm (1977)

The other key element of Hawkwind’s make-up, and the one that’s perhaps proved to be the most problematic, certainly for the average rock punter/critic, is the band’s strong identification with science fiction. SF has a more respectable standing these days, but in the 70s, it was still for the most part regarded as a low brow and essentially juvenile subculture. Yet if the early version of the band had used ‘space’ as a blunt metaphor for escaping from straight society (or just getting out of it), Calvert used science fiction as a vehicle for satire and social comment – perhaps more overtly than David Bowie, but in much the same way. As the Michael Moorcock-helmed New Worlds magazine had demonstrated, SF was ideally placed to interrogate the new existential and psychological challenges facing the human race, and Hawkwind used SF to dramatise and critique what was happening in modern society.

Calvert would not only use SF themes and ideas in his lyrics, but also base entire songs around pre-existing works, with ‘Damnation Alley’ – inspired by Roger Zelazny’s post-apocalypse pulp thriller – being the most fully-realised of these ventures. After the hazy stoner funk of Astounding Sounds, the music on Quark is bracingly up to date, with the chrome-plated ‘Damnation Alley’ cruising purposefully through a ”radiation wasteland” – it might lack the fuzzy logic and cosmic density of their earlier output, but it’s the sound of a band embracing the new wave and winning.

‘Death Trap’ from PXR5 (1979)

Hawkwind were also more than capable of embracing the punkier end of the new wave, with ‘Death Trap’ in particular presenting a manic, riff-heavy version of the year-zero sound. Released as a B-side in 1978, before appearing on the half-studio/half-live PXR5, it was actually first aired at a legendary Christmas 1977 gig in Brock’s adopted home town of Barnstaple, where Brock and an utterly wired Calvert played with members of local band Ark as the Sonic Assassins. While their peers were being dismissed as old farts and dinosaurs by a new generation of young music fans, Hawkwind gigs had long been both a sanctuary and breeding ground for the disaffected and disenfranchised, with John Lydon for one being a regular attendee. (He would later go on to attend Calvert’s wedding reception).

Hawkwind encapsulated the key tenets of punk: anti-establishment, non-conformity, DIY and against virtuosity. They showed how it was possible to operate successfully at arm’s length from the traditional music business at a time when the industry was at its strongest. Many fans recognised the value of a grassroots, music-based community that turned the audience into participants rather than spectators. As Joy Division/New Order’s Stephen Morris said on this site in 2010, “I think punk rock started because in every small town there was somebody who liked Hawkwind.”

‘Levitation’ from Levitation (1980)

By 1980, Hawkwind had gone through another of their regular personnel upheavals: Calvert and his spontaneous theatre was out, the instrumental firepower of guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton, keyboardist Tim Blake and, bizarrely enough, drumming legend Ginger Baker was in. One of the first albums recorded digitally, Levitation showcased a modern rock band confidently integrating the latest technology into their sound, with its title track being a prime example of how the dense, mantric riffs of old had been re-tooled for a new era. It also established the template for much of their music throughout the 80s and beyond, Lloyd-Langton’s super-charged lead guitar in particular pushing them towards cosmic/electro metal.

Hawkwind’s fortunes over the following decades may have waxed and waned, but they were always there, an alternative to the alternative. They were integral to the 1980s’ free festival/traveller scene, paving the way for the underground rave and techno parties that followed later in the decade, and the last ten years has seen them go through a musical renaissance – anybody looking for an entry point outside of their ‘classic’ period should check out The Machine Stops (2016) or <a href=” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sk4xnZJwIVc&list=OLAK5uy_kFvIlLQr88uNXaxg453zh1lXxHXyVq5Sk” target=”out”>Into The Woods (2017). The counterculture that birthed them might have dissipated by the end of the 70s, but Hawkwind remained as a byword for mainstream resistance and a wellspring for future generations.

Joe Banks’ Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground is published by Strange Attractor Press