There is usually nothing out of the ordinary about watching musicians setting up instruments on stage. But with Susan Alcorn, it was different – when combining all of the elements of the pedal steel guitar to assemble a full instrument, she looked like a magician preparing her props before a show.

The American composer didn’t choose the instrument with which she is most associated. Although there are outlier musicians such as David Gilmour, Heather Leigh and Christoph Hahn who use the pedal steel guitar in more unusual, say, psychedelic rock or experimental modes, it is the most readily associated with country music. Relatively young, the instrument was invented in its current form in the early 1950s – historically, it tends to have been played by ear; therefore, not much music has been written for it. In the last decades, Alcorn, who passed away at the end of January, proved how versatile this instrument truly is and just how far it has been able to travel.

“It is a difficult instrument to learn and, at times, difficult to play”, she told me when she performed at the Dni Muzyki Nowej festival in 2018 in Gdańsk, Poland, which I curated. “It’s amazing that you use so many limbs of your body – both hands, feet, and knees – for different things and that they all must be coordinated properly just to get a decent sound. It takes time and effort to learn. The most difficult is the touch of the right hand – the fingers, the control of the bar with the left hand, and the right foot on the volume pedal, which gives you an even attack and sustain of the notes.”

Alcorn was born in 1953 in Cleveland, Ohio, and developed a passion for slide guitar as a teenager. Her family was musical: her mother played piano, mostly church music, and had sung with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, while her father mimed the popular singers of the day in the 50s and 60s. In school, she took up the viola for one year, changed to cornet, got kicked out of the school band, gave up brass, and started playing guitar, dobro, Hawaiian guitar, and pedal steel.

“I started playing the guitar when I was thirteen and had always loved slide instruments’ emotive power and expressiveness,” she told me. “I had heard pedal steel guitars on records and had tried to get those same sounds on a dobro.” She became fascinated by the pedal steel guitar after seeing it played live during her political science and history studies in Northern Illinois and became hooked. For twenty years, she performed with Western swing and country bands in Chicago and later Houston. “What fascinates me the most about the best country-western music is its bare, sometimes brutal, honesty; its direct and sincere expression; and its deceptive simplicity,” she said in 2018.

After being introduced to Pauline Oliveros’s “deep listening” philosophy, she expanded her musical horizons – she has been interested in improvisation and extended techniques. “I loved the later John Coltrane, Krzysztof Penderecki, Edgard Varese, blues, and psychedelic music from an early age. So, when I began playing the pedal steel guitar, I played that kind of music, though mostly at home because of my limited abilities. Eventually, maybe I improved a little on the instrument, met other musicians with similar tastes, and began to play with them.” she admits.

She played songs by Astor Piazzolla, Curtis Mayfield, Olivier Messiaen, or nueva canción, left-leaning folk music in Chile. She played with Pauline Oliveros, Eugene Chadbourne, Peter Kowald, Ingrid Laubrock, Le Quan Ninh, Josephine Foster, Joe McPhee, Ken Vandermark, Mike Cooper, Michael Formanek, Fred Frith, Evan Parker and Mary Halvorson, among others.

“Susan’s playing was pure magic. She was totally in the moment, unique in her approach to improvisation,” Mary Halvorson, with whom Alcorn played extensively, told me. “Her playing was like electricity, and you never really knew what would happen. She was a true innovator on the pedal steel guitar and one of the great improvisers of our time. I feel lucky I got to work with her as much as I did.”

Susan Alcorn has been on three records with Nate Wooley’s Columbia Icefield and was at the centre of the last version of his Seven Storey Mountain project. “She always had great ideas, and she wasn’t afraid to speak her mind and enter into discourse about the music”, Wooley says. “We argued often, and I treasured her ability to show me when I had gone wrong with a composition and her sensitivity in seeing when something was important to me. She was a non-interchangeable voice. She was, in many ways, the engine and heart of Columbia Icefield, and I was always happy when she signed on for the next project,” he admits.

In 2007, Alcorn released And I Await the Resurrection Of The Pedal Steel Guitar – she often mentioned that she believed this instrument would see its new face. “Not much music has been written for it. I do not doubt that this will change in the future,” she admitted to me in 2018. There is very little formal education for the pedal steel guitar. Unlike guitar players, trombonists, harpists, and clarinetists, many of whom learn in conservatories, pedal steel guitarists are mostly self-taught or take private lessons from a musician they admire. She believed changing the context of the instrument was possible, and as the innovator of the pedal steel guitar, she contributed her part to it with her vast discography.

“There are certain technical and mechanical challenges with playing this instrument in different genres of music. For one, the instrument, in its present form, has pretty much been set up to play country-western (based on major triads) and swing music (heavily relying on sixth chords), so a musician needs to relearn, re-tune, and reconfigure the instrument to be able to accommodate different or more complex musical forms”, she said. “Changing the context is possible. As for important, I think that’s an individual thing. I think everyone should play the music that speaks to them, that they have a burning need to express. If that need takes them beyond the borders of the ordinary, then they need to do what they have to do, learn what they need to learn, to express that.”

Susan Alcorn & Eugene Chadbourne – ‘I Got Caught’ from An Afternoon In Austin.. Or Country Music For Harmolodic Souls (1998)

We have a classic country song here, one of the hits of Loretta Lynn, who has been around for six decades and has released many gold albums. Eugene Chadbourne, who gravitated between Anthony Braxton and Derek Bailey, sings here in an entirely differently manner than the original, more like a native singer than a saloon performer. Alcorn plays the original parts, presenting the song as if seen through a lens, revealing the instrument’s place in the country context. Lightly guided chords build a distinctive background against which Chadbourne sings a song about cheating and plays the guitar. At the same time, this seems to be a key moment in Alcorn’s transition, which sets her on a new path – still immersed in country music but starting to look at classics of the genre with a very open-minded approach. “I love the sound of pedal steel guitar in country music, and it is not easy to play well. I spent so many hours learning in this style by copying note-for-note what the great Nashville musicians at the time were playing,” she told me in 2018. “I still enjoy playing country music on the rare occasions I can do that. However, the music from the deepest part of me, perhaps the deepest part of us, is different.”

Susan Alcorn – ‘O. Sacrum Convivium’ from Curandera (2003)

Starting from country music and getting to Olivier Messiaen, the French composer, organist, and ornithologist, is probably a unique aspect of Susan Alcorn’s discography. This composition, published in 1937, is a short motet for a four-part mixed chorus and Alcorn admitted that she cried on hearing it for the first time. Her interpretation has the stillness of the original; the sounds are transitory, and she highlights structural and spiritual aspects simultaneously. Messiaen’s music inspired Alcorn to change from playing a 10-string to a 12-string in order to be able to play lower notes. “My tuning is slightly different from most other steel guitarists, probably different from all of them. Every time you change a tuning or add more strings, there is a definite learning curve. It takes a long time and effort to get used to playing an instrument with a different tuning and a different number of strings” she said.

Susan Alcorn – ‘And I Await the Resurrection of the Pedal Steel Guitar’ from And I Await the Resurrection of the Pedal Steel Guitar (2007)

A composition influenced by Messiaen’s work. When Alcorn heard ‘Et Exspecto Ressurectionem Mortuoram’ on her way to a country and western gig in Houston, Texas, she had to stop on the motorway because she was so impressed. The fifteen-minute contemplative piece smolders quietly in contrast to Alcorn’s later, more dynamic works, more in the meditative spirit of Messiaen’s pieces. This song is, in part, an homage to this monumental work by Messiaen, with which it shares the first three notes but also expresses her feelings on the current state of the pedal steel guitar and her hopes for its future. In this piece, she wanted to tell the story with the whole body of the instrument – the legs, the pedals, the wood, the strings, the tuning keys, the bridge and nut, and the pickup. It shows a broad spectrum – from point-like, more aggressive bass strokes to delays. The elaborate suite impresses with its spaciousness, delicacy, and monumental approach, although it sounds subtle and minimalist, basically smoldering and not attacking with a sound like in Alcorn’s later lineups and when playing country.

Susan Alcorn – ‘Soledad’ from Soledad (2015)

Astor Piazzolla became famous as a composer of the nuevo tango, which at the same time overshadowed his more eccentric achievements. Alcorn had wanted to perform his music since she saw him play live in Houston during 1987. By interpreting his pieces on the pedal steel guitar, she approached them in a no less eccentric way however. ‘Soledad’, originally a danceable piece, is slowed down almost wholly, until it meanders sentimentally, with melancholy, like a nocturne, turning its uptempo rhythm into reverie and solemnity. The diverse instrumentation of the original, including piano and accordion, is transformed and unified by Alcorn, its vibrancy concentrated cohesively into a singular sound. ‘These encounters inform my music and hopefully help me grow as a musician and person. My love for Astor Piazzolla’s music and the compulsion to learn and record some of it started when I saw him perform in Houston, Texas, with a sextet – that feeling has never left.’ she summed up.

Mary Halvorson Octet – ‘The Absolute Almost’ from Away with You (2016)

Watching the Mary Halvorson Octet and witnessing how they performed live together was one of the most enjoyable experiences I have experienced in jazz-related music. This track starts with Alcorn’s solo, in which she plays everything from heart-rending melodies to grating noise until she is gradually joined by other instrumentalists – first by Halvorson herself and then by the rest of the band when the piece becomes more orchestral, exploding in the second part. “When she played in my octet, I always thought of her as the ‘glue’,” Halvorson told me. “Her sound was everywhere: singing alongside the horns, dueling guitars with me, diving into low bass register stuff, and all sorts of crazy sonics”. Halvorson’s lineup initially functioned as a septet, but it was not until 2015 that she decided to add another instrument and contacted Alcorn to play with them. It was a challenge to write for a pedal steel guitar – they corresponded for several months about the parts she had written for Alcorn to play. “When Susan was learning my octet music, she spent months painstakingly transcribing each chart into her own special pedal steel notation, pages upon pages of detailed notes for each piece of music,” remembers Halvorson. “Ultimately, she decided to memorize everything because it was easier than dealing with the complicated scores”.

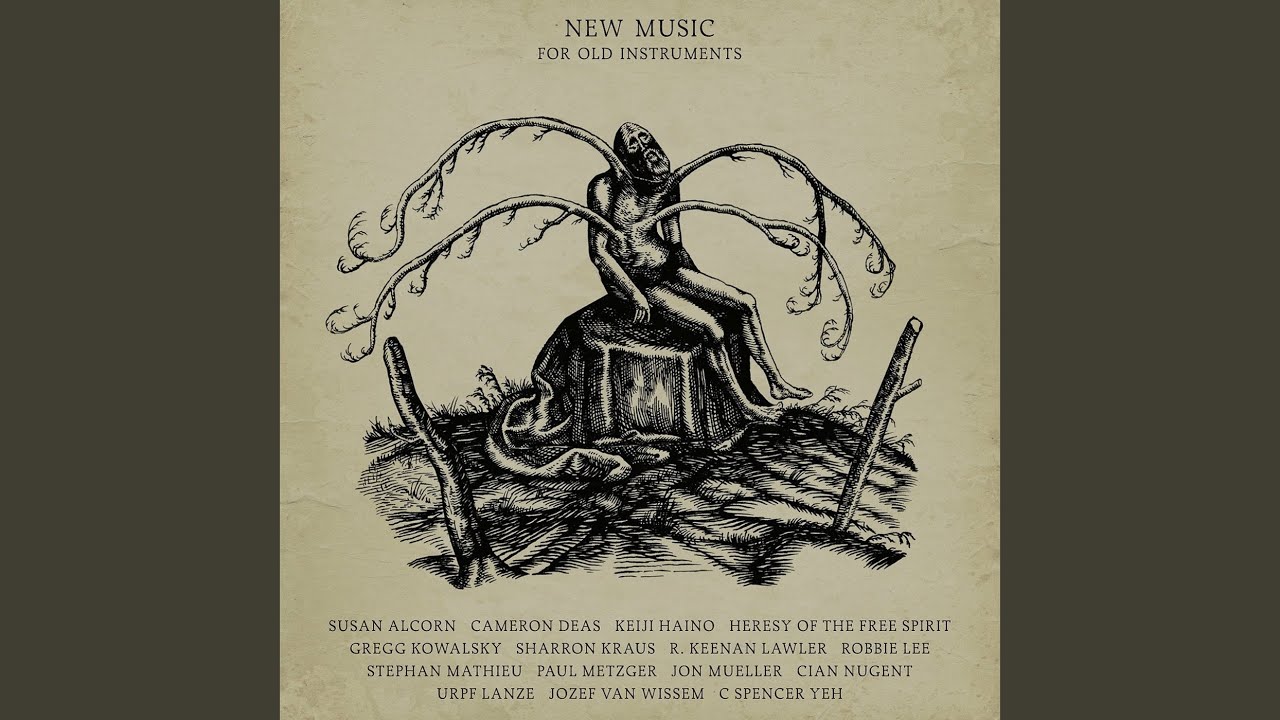

Susan Alcorn – ‘Sapphire’ from New Music For Old Instruments (2012)

‘Sapphire’ is unique in Susan Alcorn’s oeuvre due to the use of extended techniques. While in most cases, the pedal steel guitar arrangements – whether reinterpretations or original pieces – are very complex and progressive, here, the focus is on a case study of the instrument. Alcorn emphasises its reverberation, the vibrating soundboard, the sound of the amplifier, and the thickened timbre. The lightness of the pedal steel guitar is transformed into heaviness, as if a fragment of a post metal session, an afterimage of reverberation. The composition was included on the New Music For Old Instruments compilation, which resulted from the festival of the same name, curated by Jozef Van Wissem. This sheds new light on Alcorn’s work, juxtaposed with the work of such artists as Gregg Kowalsky, C. Spencer Yeh, and the compiler himself, among others, because it breaks down sonic clichés of the pedal steel guitar in a country and western context. Stephen O’Malley included this piece a mix for FACT magazine, which showed that Alcorn’s approach of broadening the spectrum and cognitive possibilities of the pedal steel guitar was gaining more and more traction.

Susan Alcorn, Joe McPhee, Ken Vandermark – ‘Invitation To A Dream’ from Invitation To A Dream (2019)

The result of a unique improvisation in which Alcorn met the titans of the Chicago improv scene. This unique collaboration between two brass players during a session (preceded by several concerts) resulted in a different, subdued, arguably more ambient take on pedal steel guitar. In the first part, Alcorn’s instrument smoulders imperceptibly in the background, making room for McPhee and Vandermark. However, the subtle music does not reach its climax. It does not explode, although the instrument does, however, take on a post rock, slightly cosmic space halfway through, only to come more to the foreground in the last part of the piece. It creates a delicately painted arrangement with the hiss of metallic instruments. “Creating successful, completely improvised music in a studio is often challenging. On each occasion I had to play with Susan, she had the remarkable ability to channel that sonic environment, opening the music up and out exquisitely”, Ken Vandermark told me. “On this occasion, the music established an amazing, introspective space sustained throughout the recording process and led to the title of the album, Invitation To A Dream. We knew we caught something rare that day.”

Nate Wooley – ‘Lionel Trilling’ from Columbia Icefield (2019)

When I came across the first Columbia Icefield record, I couldn’t get enough of it. From strict composition to improvisation, through mutual attention and a brilliant, unfolding mystical mystery. Nate Wooley and his quartet have created an engaging and intimidating work of great scope. ‘Lionel Trilling’ is perhaps most notable for the meticulous assignment of the role of each musician – Wooley wrote this material with these musicians in mind. The dialogue between Halvorson and Alcorn is particularly captivating – they converse while playing in a different time signature and gradually build up a mood counterpointed by Wooley and Savery’s rough, bordering on destructive sound. In the 13th minute, the musicians return to the opening motif, and the sonic escapade becomes a march: a roaring and electrified trumpet sets the rhythm with the growing percussion, and the subtle guitars are a good counterpoint. This balances the timbre of the sound and the dynamics and tension between the musicians. Nate Wooley met Alcorn at a ‘blind-date’ duo gig, which led to their cooperation. “Within thirty seconds of playing, I was completely in love with Susan’s sound and uncanny ability to steer the improvisation onto new and unexpected paths” Wooley told me. “A few years later, I was in a car driving to the source of the Columbia River in Canada. As the ice field that feeds the river loomed into view, I heard a specific music in my head. This was unusual, so I wrote everything I could think of on a napkin. That music became my band, Columbia Icefield. And looking at the napkin recently, I saw the first two words were: SUSAN ALCORN”.

Susan Alcorn Quintet – ‘A Night in Gdańsk’ from Pedernal (2021)

After many years of playing in various lineups of other people’s bands, Alcorn formed a quintet of which she was the leader. As in Halvorson’s Octet, the sonic sisterhood of string instruments shines dynamically, notably when snippets of melody emerge. Pedernal is meticulously composed but with room for the players to breathe, with frivolity – like when tackling the melodic blues motif in the title track or the quasi-folk phrases. In addition to the orchestrations, there is also room for more minimalist and delicate ideas to emerge, such as ‘A Night In Gdańsk’, which was originally written for solo performance. The band creates a great counterpoint on the verge of silence, building a nuanced texture with bowed, strummed and plucked strings. The melody hides between the string instruments or disappears entirely into the texture. The Quintet paints a broad musical spectrum – from dense forms to lyrical folk motifs. Mary Halvorson: “I love the music Susan has created – it is unique and unlike anything else. The process was very intense – it took me a long time to get to know it. I listened to the demo, trying to understand my role and how it would all sound. We had long rehearsals, and I felt very present throughout the process.”

Susan Alcorn, Septeto del Sur – ‘Suite Para Todos’ from Canto (2023)

Canto was born from Alcorn’s fascination with Chilean culture, which lasted almost two decades. Her group, Septeto del Sur, combines Chilean folk and nueva cancion (a type of folk that became popular in the 1960s and was banned by Pinochet in 1973) with improvisation and contemporary music. The opening track of the album, ‘Suite Para Todos’, is a captivating composition at the crossroads of different worlds. The steel guitar solos are fascinating and blend perfectly with the quena, zampoña, cuatro guitars, and the charango, creating a melancholic yet rich sound. There is room for dignity, airiness, and impetuosity. Alcorn plays here with a band that balances on the edge of jazz and folk, building a dense and complex arrangement. A dignified arrangement opens the piece; in the middle, there is room for the delicate and charming sound of the pedal steel guitar, which leads the piece into a lyrical and melancholic state. In the finale, Alcorn returns to the motif that builds the basis of the composition outlined at the beginning. The effect is light, airy, and stunning.