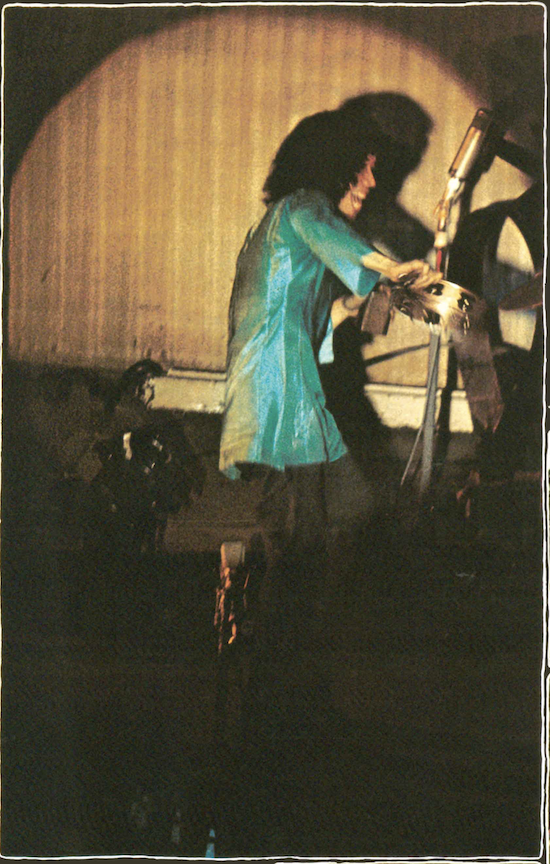

Stomu Yamash’ta courtesy of King Records

Of all the artists who have managed a lifetime of extremity in sound, Stomu Yamash’ta, a Japanese percussionist, born Tsutomu Yamashita, has a discography that begs for reconsideration. Between his early beginnings in classical music, forays into jazz and progressive rock and a fundamental attachment to spiritual tradition; his drums, chimes, gongs and other unique instruments have graced many genres with unusual timbres.

Amongst the immense recognition and opportunities experienced by him, episodes of his biography affirm an enigma across many levels – mysterious science-fiction films, an original jazz-fusion stage show production, performances using volcanic rocks and a prolific, all-star list of collaborators. Later in life he retired to a temple where he channeled music for ritualistic purposes, but his entire life story represents a dynamic collision of ideas experienced by many Japanese renegades after the Second World War.

Yamash’ta’s acrobatic drumming caught the attention of big names in the classical world at a young age. Performing with Kyoto’s

prestigious orchestras when he was still in his teens he moved across instruments with such speed that his hair waved with each gesture and strike. Composers including Hans Werner Henze, Peter

Maxwell Davies and Toru Takemitsu wrote music especially for him.

In July 1969 Time described one of these performances: “He nudged, banged, tickled and teased the instruments. At one point he flailed away with both hands, simultaneously blowing onto bamboo sticks, kicking the prayer bells and rubbing his body frenziedly against the gongs. After it was all over, the audience gave him a standing ovation.”

Outside of his showmanship, his expansion of the classical percussion section crucially coincided with avant garde sound

experiments which invited attention from John Cage and from Tokyo’s underground jazz circles.

His atonal, improvised rhythms broke free from traditional frameworks while also appealing to archaic sensibilities of

silence and duration, in the manner of Shintoist court music or Buddhist ritual. In opening up unexplored territories of sound, the special ambiences he created signified a new sense of the unknown for the public, something that would be proven in his

scoring of some of the most peculiar films of the 1970s (including Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth).

Yamash’ta spent a considerable amount of time in Europe and America, but in a Japanese context his tendencies centred him at the confluence of his country’s underground jazz and rock scenes. A short chapter on him in Julian Cope’s Japrocksampler traces collaborations with experimental jazz pianist Masahiko Sato, or Fluxus violinist and Takehisa Kosugi of The Taj-Mahal Travellers, and highlights his escalating jazz fusion spectacle – an elaborate production called The Red Buddha Theatre – plus his once-in-a-generation prog-rock supergroup Go.

Cope suggests Yamash’ta’s artistry was sabotaged by international possibilities, but his wonderfully abnormal trajectory tells of what a Japanese musical appetite can do when it is free to explore a plethora of foreign influence. "Like punks gate-crashing a wine-tasting" is how Cope described this unusual synthesis.

From his intensifying theatrics all the way to his monastic retreat; through all these various encounters his cosmic percussion breathes with a unique tactility. As a lost genius awaiting re-discovery, a hidden diagram of tradition and modernity plus East and West is contained in a flood that cannot be contained by a single context.

Yamash’ta in full flight, detail from Sunrise From West Sea

Yamash’ta & The Horizon – ‘Sunrise From West Sea Part 1’ from Sunrise From West Sea "Live" (1971)

Among the many dizzying sonic excursions relished by Japanese hippies in the 1970s, Sunrise From West Sea "Live" – reissued this month by We Want Sounds for the first time since its release – exemplifies the extremities pursued by Tokyo’s underground jazz freaks. Alongside the 24-year-old Stomu Yamsh’ta, are distinguished experimental pianist Masahiko Satoh who composed the unparalleled cult-watercolor-anime Belladonna Of Sadness (1973), Takehisa Kosugi, key member of the eccentric Taj-Mahal Travellers ensemble, and Hideaki Sakurai, an electric shamisen player, to summon what they conceived as new ‘horizons’ of uniquely Japanese jazz. A spaced-out cacophony in the manner of The Taj-Mahal Travellers’ spontaneous drone improvisations Sunrise was recorded during an invite-only concert at Tokyo’s Yamaha Hall that lasted all night. This LP, in fact, only documents a fragment of the evening’s proceedings. Electric kotos, organs, confused chanting, human cries, theremins and radio noises resound as much as Yamash’ta’s own spontaneous collisions. These textures suggest the stimulations of nascent modern art-music. This mediation between noise and silence concretises links between Buddhist philosophy and traditional percussion, manifested in a renegade masterpiece.

Stomu Yamash’ta – ‘Red Buddha’ from Red Buddha (1971)

1971, the year of Stomu Yamash’ta’s debut, was also perhaps the busiest of his career as it saw him releasing six albums and two film scores. Amongst these was Red Buddha recorded less than a week before Sunrise From West Sea "Live". This album in particular crystallises the golden beginnings of a long adventure between Eastern traditions, classical conventions and modern techniques. During the title track, a pattering tabla guides us through a 15-minute fog of clangs, chimes and frenetically wavering mouth harp. Introducing the pacing of gagaku to musique concrète, timbres are controlled within improvised gestures, as Yamash’ta, proves himself once again to be one who makes beautiful sounds with whatever he touches. As he actively transitions between instruments and rhythm, live percussion is also captured alongside the playback of previously recorded tracks to thicken its hazy soup.

Stomu Yamash’ta & Masahiko Satō – ‘Metempsychosis I’ from Metempsychosis (1971)

Even among all abstract percussive seances, Metempsychosis was a particularly wild jazz recording, conjured alongside Masahiko Satoh and the 17-member New Herd Orchestra. The pianist Satoh had gathered fame for his award-winning Palladium (1969), an elegant record which flowed like water, but one which was immediately followed by Deformation, a cacophony loaded with crashing pianos, sirens, and frog-like voices. Meeting Yamash’ta in Boston, the two realised they shared an obsession with the avant jazz circles blossoming around them and together eventually recorded Metempsychosis in a single evening. It is a true ‘transmigration of the soul’ as the title denotes, an epic work composed of two side-long tracks composed and notated by Satoh. His directions gave plenty of room for Yamash’ta’s adlib thumps and crashes, framed around a session of four trumpeters, four trombonists, four sax players and a bassoonist. The result is one Julian Cope describes in Japrocksampler as “music that was way beyond jazz and approached a kind of

Godhead union between Sun Ra and the Cosmic Jokers”.

Tsutomu Yamashita/ Seiji Ozawa/ Toru Takemitsu/ Maki Ishii/ Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra – ‘Cassiopeia’ from Cassiopeia/ Sōgū II

As if soundtracking the opening scenes of a classic thriller like Woman In The Dunes (1964), Toru Takemitsu’s atonal piece for Yamash’ta and the Japan Philharmonic Orchestra swells like the arc of a flickering, black-and-white picture. Near quarter of an hour in, Yamash’ta’s percussion, relatively minimal until then, suddenly explodes into banging and clattering to the extent that his role as a ‘solo’ percussionist easily drops jaws. Amongst several other composers that approached Yamash’ta – such as Peter Maxwell Davies and Hans Werner Henze – Toru Takemitsu was an important mentor, and they shared a similar habit of troubling the fixed conventions of Western music with liquid composition. Takemitsu’s work helped to define Japanese cinema during its Golden Age and he scored over 90 films including compositions for Akira Kurosawa and Kenji Mizoguchi. Likewise the percussive style of Yamash’ta was much in demand by Japanese studios, his technique a worthy device to convey the unknown, an exposure which would eventually bring him to the attention of Western film makers.

Stomu Yamash’ta — ‘One Way’ from Come To The Edge: Floating Music (1972)

As the leading actor, David Bowie was originally approached to provide the soundtrack to Nicolas Roeg’s science-fiction feature The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976), but contractual complications meant the director had to look elsewhere. Rumours of a long lost recording by Bowie languishing in a vault has

since amped up the cult film’s already mysterious qualities. The actual soundtrack, alongside compositions by John Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas, also included many contributions from Stomu Yamash’ta. First appearing on his 1972 album Come To The Edge, ‘One Way’ was a whispering, rattling soundscape that

begins with the sho (a Japanese mouth organ used in medieval court music) and ends in what sounds like repeated collisions between pan pots and vibraphones. A combination of 70s kitsch with religious ritual, this kind of song helped pave the way for his new English prog-rock ensemble.

Stomu Yamash’ta’s Red Buddha Theatre – ‘Awa Odori’ from The Man From The East (1973)

Yamash’ta’s double life as avant-percussionist and jazz-rock figurehead became more entrenched after the success of Come To The Edge which saw him invite over 30 stage actors from Japan to form his Red Buddha Theatre group. Yamash’ta’s highly unique stage production incorporated elements of Noh theatre, kabuki,

and mime into live jazz-fusion, holding grandiose residencies in Paris and even performing at London’s Roundhouse. As per the intention of placing himself in European surroundings he was able to showcase himself as ‘The Man From The East’. The accompanying album – which saw him enrol Brian Gascoigne, a composer credited for The Dark Crystal‘s electronic soundtrack – resulted in the most ostentatious concoctions of prog rock and Japanese folk. On one hand, the album seemed to only project superficial perspectives on Eastern traditions, hollowing out its dignified, atonal ritual. To Cope, the theatre made Yamash’ta an “exotic freak whose proto-Rick Wakeman garb and dervish-like agility became entirely secondary to the worthy countering of his unremarkable band.” But on the other, its style also appears to savour the carnivalesque atmospheres of Tokyo’s underground theatre troupes, such as the extravagant and rebellious Tenjō Sajiki, lead by surrealist poet Shūji Terayama and scored by in-house composer J.A. Caeser. Full of melodrama, the sounds are a dynamic visual experiment by an artist whose focus had until then been solidly monolithic.

Go – ‘Crossing The Line’ from Go (1976)

Yamash’ta’s increasing involvement with the 70s prog spectacle culminated in ‘Go’, a stylistically diverse supergroup whose all-star cast forged a genre-hopping milestone. As well as the self-titled record, a live album, Go Live From Paris propelled the energy of this short-lived union. Melody Maker best described their cosmic level spectacle in a few words: “Go combines Stomu Yamash’ta, Mike Shrieve, Steve Winwood, guitarists Al Di Meola, Bernie Holland, and Pat Thrall, ex Tangerine Dream synthesizer player Klaus Schulze, bassist Rosko Gee, conga players, an orchestra conducted by Paul Buckmaster, Thunder Thighs, a kung fu fight sequence, two gymnasts, two acrobats, a juggler, four dancers, a tiger, a swan, strobes, two banks of TV screens, National Aeronautics and Space Administration movies and multibeam back projections onto two cinema screens.” The blinding extravaganza may have been the tipping point leading immediately to Yamash’ta’s sudden withdrawal to a temple in Kyoto, but the record also shows how the world of synthesisers has informed all of his work since. As well as the shimmers of Japanese ambient

music, its funk grooves, ambient arrangements, krautrock futurisms and stadium-rock tinged moments of glamour pour seamlessly through otherworldly rhythms and timbres.

Stomu Yamash’ta — ‘Touched’ from Sea And Sky (1984)

Yamash’ta had retired from public view by the 1980s, instead devoting himself to a new mission: to pursue Buddhist concepts through meditative soundscapes. The cycle of albums created in his gradual re-emergence diffused the humility of Japanese aesthetics into sparse percussion. Sea And Sky is driven by expansive energies, but its majestic Vangelis-like arrangements are subdued by sustained tones; gongs and chimes are enveloped by softly-deployed electronics. These tracks (when the titles are placed together they spell ‘A photon appeared and touched, Ah… time to see, to know’) have the dark, cinematic feeling of the cult sci-fi films he scored earlier, but with a newfound, innocent sense of serenity.

Stomu Yamash’ta – ‘Dancing Stone’ from Listen To The Future Vol. 1 = 懐かしき未来 (2002)

After devoting his music to spiritual purposes, Yamash’ta encountered a material which becomes his main instrument: a special volcanic rock found on the island of Shikoku called sanukit. Once valued by ancient Buddhist monks who used their booming sounds as an aid to meditation, sanukit suggested unlimited potential to Yamash’ta due to the harmonic ranges of its deep, metallic resonance. After teaming up with a stone researcher to create a unique instrument – the ‘sanukitophone’ – he explored their vibrations, using them for religious ceremonies and special commissions including a performance at Stonehenge in 1990. Much of this more recent work is particularly hard to come across, but his 2001 release Listen To The Future Vol. 1 best showcases the stone’s mysterious qualities in action. Having

experienced countless spheres of music in their modern constellations, his late work has been a return to introspective rituals in tune with the earth of his native land.

Bonus Film Scores

John Williams & Stomu Yamash’ta – ‘In Search Of Unicorns’ from Images (1972)

Though it was the American music composer John Williams who received the Oscar for scoring Robert Altman’s 1972 psychological thriller Images, it is Stomu Yamash’ta’s unnerving sounds which linger jarringly around each of its vignettes. To accent the very 70s sense of paranoia the film embodies, Yamash’ta’s

unconventional sounds – dissonant crashes and shakuhachi-like flute screeches – help convey the spiralling plot line of a lonely writer suffering hallucinations in her vacation home.

Peter Maxwell Davies – The Devils (1971)

Based loosely on Aldous Huxley’s The Devils Of Loudun, cosmic soundscapes help to drive an unhinged story of 17th century catholic nuns descending into evil and chaos. Looming intensely alongside the compositions of Peter Maxwell Davies, atmosphere takes centre stage in Ken Russell’s narrative which

delves graphically into themes of violence, sexuality and religion, creating bad tingles with satanic timbres.

Brian Gascoigne – Phase IV (1974)

If jazz-fusion collaborations between Yamash’ta and Brian Gascoigne – the synth player responsible for the sounds of ‘dark’ Muppet film The Dark Crystal – does not intrigue enough, then their joint scoring of 1974’s Phase IV, a cult science-fiction thriller about ants rising to take over the world, ought to. The film’s Jodorowksy-like symbolism is grounded in the monolithic beauty of Yamash’ta’s traditional instrumentation, but during montage sequences in which cryptic phenomena are clinically explained, its rattling discord rouses an acute sense of unease which creeps directly across the soles of one’s feet.