1971: The Intruder, Granada TV.

I was under 16 when I made it. It was filmed on location in Ravenglass in Cumberland, near an atomic power station, and it was significant for a lot of reasons. It was very original, a very scary script. I used to get the NME sent to the post office and it’d always come about four or five days too late, and there were some girls in the village, who were quite exciting.

It was the first time I’d been away on location on my own, and Ravenglass is an extraordinary village because it’s only got two streets, and there’s a miniature railway that goes up through the mountains. Because it was a Granada TV production we also did some studio work in Manchester, where I’d stay in digs in Whalley Range and I went to see Yes at the Manchester Free Trade Hall. I was dead impressed.

My interest in music was piqued by studying in London. I went to a drama school called Arts Educational Trust, there were lots of girls, I did ballet and modern tap, and because this school had an agent I started acting, I lived in Soho in digs above the Shaftesbury Theatre, and Hair the musical was on, and I discovered the Marquee Club.

Everything came at the same time, acting, doing radio, music, seeing bands all the time. I don’t know how I did it really, but I was dumped in London at the age of 15 with nobody looking after me, no parents around. It was exciting but lonely. I don’t know if I am unscathed! haha. There was some weird shit going on. Music saved me.

1973: The first Simon Turner album

When I was about 16 I was introduced to Jonathan King, and he said ‘do you want to make an album?’ It was come and meet the parents, everything like that. I just got on with it really, because why wouldn’t you make an album? I was really naive, incredibly naive. I was into guitarists by then… the record is rubbish. I know what they were trying to do, they were trying to do a teen thing, and it was interesting, it made me big-headed and obnoxious and pretty ridiculous, going to Manchester to do record shop appearances and Radio Luxembourg road show appearances, Peter Powell going ‘yeah Simon!’, meeting Slade, lots of girls, a lot more than in Ravenglass. It was a very surreal time, a bit B-grade I think, not exactly hitting the top spot, though Slade were very nice guys. This is still when I was 16, 17-years-old. I had a column in Diana magazine, called Simon Sez. I wrote about my cat, going to gigs, and 10cc.

I didn’t even like my music at the time, we did ‘Can I Have My Money Back?’, that was good, ‘Wild Thing’ was an appalling cover, I mean really rubbish, and I can’t remember the others. I’ve not listened to it for years. I was allowed to write b-sides for singles, I did one that sounded like a Tubular Bells, ‘Five Years’ combination, me trying to be Mike Oldfield trying to be like David Bowie. Stupid. Young, dumb, bad. Failure. I got out of my contract with Jonathan, thank God, and made a record with Judge Dredd, a reggae thing, which was fine, couldn’t get a deal, then I went ‘I hate this pop music’, horrible songs I didn’t like. It was so not me. I wanted to sound like Mountain, why can’t I do a song like Steppenwolf or Iron Butterfly? I rejected pop.

Simon Fisher Turner and Captain Sensible at an Iggy Pop show at Friars, Aylesbury

America

I’d been before, to do promo and fashion shoots for UK Records. Then I went to LA to audition to replace David Cassidy in the Partridge Family. I was going to be David’s English cousin. Ridiculous. But I did get to go and see Hot Tuna at the Hollywood Palladium. The second time in New York must have been around ’76, just before the first Talking Heads album, and that was CBGBs… I was looking after David Bowie’s house in New York, which sounds ridiculous, but I knew Angela and that lot and he was in LA. I’m good at house sitting, actually. The press officer for UK Records in New York, she took me down to CBGBs, and I saw Talking Heads as a three piece, which was magnificent. I was hanging around in dark bars, it was fun, obviously, Wayne County, it was draggy… lots of going out and not really knowing where you are, lots of naughtiness in every sense. I was exposed to a lot of craziness. Later on I went back to New York to record Marianne Faithfull for The Last Of England.

The Synthesiser

When I was lonely as a child wandering around London, there used to be a record shop in Haymarket. I don’t know what it was called, but you went downstairs and they had an electronic music section. So Terry Riley, Emerson Lake & Palmer, Roxy Music, the Clockwork Orange soundtrack, the first Faust album. Later on though, Depeche Mode, I hated it. Pop, I keep on falling into this pop thing, I hated pop. I liked the odd song, and still do, but generally I don’t like pop music. I’m a music snob. I had a Wasp portable synthesiser, it was really exciting, really great, but then I was out of there. Suicide I didn’t get first time around at all, but then I did get Arthur Brown & Kingdom Come, they made an amazing album just with drum machine and guitarist. I was always going for sounds, did love drum machines, didn’t love drum machines, did love synths, didn’t love synths. I was more into tape recorders really. Then again, I’ve been listening to Oneohtrix Point Never and I really want to make an album completely synthetically, with no natural sounds at all, which would be a real first for me. I’m really beginning to love the clarity of really plain, synthetic electronics. There’s actually quite a lot synth on the Epic Of Everest soundtrack, because I can plug in my Mac and just play around, use little bits. They’re fantastic to just explore with. I do have a synth concept album that Daniel Miller and I have talked about, which is taking classic albums that don’t have synths on and playing the whole thing on synths. Who knows. Synth pop, couldn’t do it, but now I love Depeche Mode. I just struggle with the pop shape, maybe it’s that? I struggle with the three minutes.

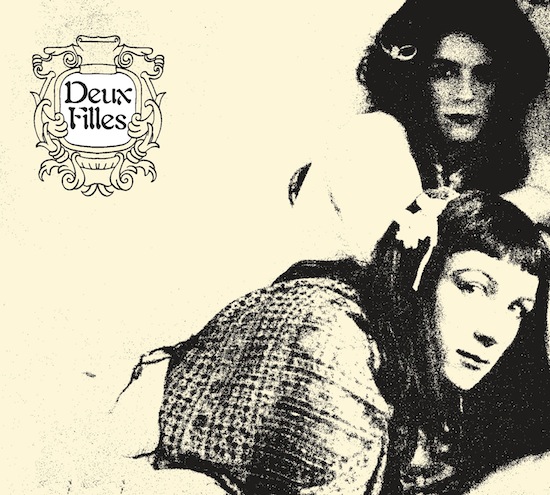

Deux Filles

Deux Filles came about because Colin Lloyd Tucker and I were playing with Matt from The The in a three-piece group, we did a residency at the Marquee, and the group got bigger, with Zeke from Orange Juice, Jim Foetus and it grew into the drugged-up supergroup, and Colin and I just got pissed off with it. I think they were druggers and we were drinkers, so that was it. So he and I went off, sat with our mate Phillip and came up with this idea of quiet music, let’s pretend to be somebody else. I’d taken tapes around record companies trying to get a deal with quiet music I’d recorded, influenced by Terry Riley, early Eno, discrete music, all the Opal label stuff, but nobody was interested. But then we came up with the idea that if we were two French girls… what’s the difference? So we borrowed a thousand quid and self-financed an album, and took it to Rough Trade and sold them the idea that I managed these two French girls. They went, ‘yeah great!’ It was spoken word by women, and the rest was by us. We played live once and dragged up, supporting the Monochrome Set at The Venue. Then Colin and I fell out, as you do. He got a record deal and I didn’t.

King Of Luxembourg

Mike Alway who worked at Cherry Red started El records an came up with the idea of this concept based on dressing up and pretty pictures and silly names. He gave us a list of who we might like to be, and we chose the King Of Luxembourg. He gave us specific instructions: no bass, and we were just dumped in the studio for a week. It was hard work, but a really good concept.

It involved dressing up, stories, inventing characters, grown-up acting. One character was Clovis, the King’s manservant, so I could write about Clovis, and then we found someone who really wanted to be Clovis, a friend of [Derek] Jarman’s. He loved being Clovis. We did a terrible gig in London where Clovis became part of the band. We had all these early music instruments, crumhorns, this very Elizabethan sound. We did a cover of ‘Poptones’ on the second album, it’s nice, it’s very soft. I still want to do another King Of Luxembourg album.

Derek Jarman – Caravaggio

I met Derek Jarman when they were finishing Jubilee. I made a mean salad dressing, and got a job at the production office, making lunch. I was a driver too, driving Adam Ant and Derek, helping him move paintings around and stuff like that – I got onto The Tempest because Derek said ‘you can drive, can you get some candles from the East End?’ Before Caravaggio, I’d had a bicycle accident, I was living in Hackney, I had no money. Someone called and said ‘can you come to the production office at the BFI to answer the phones?’ On the Friday they said ‘do you want to be in it or on it?’ I said ‘on it!’ They said ‘you can’t do the music!’ They got me doing the extras, we walked around Soho the next day and he showed me how to get extras, which is basically picking up people.

Simon Fisher Turner with Derek Jarman and Tilda Swinton

Then at the end Derek went off to record sound in Italy, he wanted real rain, real Italian sounds. That’s how interested he was, he didn’t just want sound effects. He brought all the tapes back, and I’d just brought out a solo album called A Bone Of Desire and he was jumping around and really liked a song, and he said ‘I know, why don’t you do the music?’. Caravaggio was a hoot, I’m still in touch with Spencer and Tilda, everybody still knows each other.

Derek Jarman – Edward II

The interesting thing about Edward II is that Derek never wanted me to do the music. It was only an accident that I got to do it. I’m pretty certain he wanted Sleazy [Peter Christopherson] to do it, and of course that would have been brilliant. I really wish Peter had done it, because I’d have loved to hear it. I was in the right place at the right time. I was in the French House in Soho, and George, who was going to be the editor of Edward II, came in and said ‘oh I’ve just been to see Derek round the corner, he’s got the money for Edward II, why don’t we go and see him after lunch?’ I said ‘oh well he always wanted someone else to do it’, but we had a glass of wine and went up to the production office, he was looking through Spotlight, starting to cast stuff, and he went ‘Simon is going to do the music’. That’s how his crews got together. I was always recording on location, but because we had money for this one I had a studio, a music room off the production office with cassette machines and a Revox. This meant that I could really record the whole process of the shoot, and take stuff from that, and Derek would come in and I’d play him noises. It was such an interesting space to record. I made loops and octaves, and played things, and funnily enough I’m back to that now with the Epic Of Everest. Edward II worked out well, it was hard. When Derek used to come down to studio we’d always pretend that everything had broken and we couldn’t play him anything, that was a really good trick and we did it quite often. I don’t know if he ever worked it out.

Simon Fisher Turner and Tilda Swinton

Silence

I wasn’t really aware how important silence was. When you start reading about musicians and composers, and they’re going on about John Cage… who I get and I don’t get, as I think you should do. I bought his Book Of Silence and got halfway through it and thought ‘if I carry on reading this I’m never going to do anything again in my life’. That’s when I realised John Cage was important and anything I want to do he’s probably done it. Silence. Arvo Part. There’s a man who introduced a different kind of silence for me, because silence is also a kind of stillness. There was a Deux Filles album called Silence & Wisdom. The whole thing with silence is just listening, I’ve never been to an anechoic chamber so I’ve never heard silence, I’ve never heard my blood go round my body and I don’t want to. Derek and I did a track for a compilation based around silence, and it was all about thinking about silence, and how one makes silence. The nearest I’ve come to making silence is digital silence, where in a film you want to put in silence, which is so powerful. I’ve just done a track for Optical Sound, a French label, and they’ve got a blood red limited edition vinyl coming out called Music For Death, and there’s a Coil track on there, various people. My track starts with about a minute and a half of silence, because of what follows afterwards: I’m making a statement.

The Great White Silence / The Epic Of Everest

Trying to put sound into these silent films is terrifying, because there’s nothing. Where do you start? How do I begin? And once you take silence away it’s a bugger to get it in again. I approached The Epic Of Everest in the same was as I was going to do The Great White Silence. The director’s daughter is still alive, and she’s still got the camera he used and his boots by the front door, all this stuff, there’s a gas stove that they found in Irving’s tent near the top, but I never recorded any of them. It seemed so easy – that’s what we did on The Great White Silence, we got the bell, Chris Watson recorded the silence in Scott’s hut, which of course isn’t silent. So on Epic Of Everest I just played so much more, though it was minimal. The first eight minutes there are just two things playing. You think of Everest and think ‘brass brass brass’, and then one day the penny dropped – Cosey Fanni Tutti, that sound, nobody else makes that sound, it’s totally unique, it’s fantastic. She was really great, she played on a couple of bits then I sampled her. She’s all over the soundtrack, she almost replaced my French horn sounds which I’d been using. I did try recording a whole lot of stuff and some of it was dreadful, but that’s how I work – collect collect collect. I didn’t want to ask Touch if they had some recording of water dripping down a glacier, that’s not what it’s about for me. For me doing Epic Of Everest is like having a baby, I really care, I super care about this. It’s taken so long.

Collaborating with Factory Floor at the ICA

Dear old Factory Floor. There’s a little bit of Factory Floor on The Epic Of Everest, and it’s not Gabe’s dog Vince farting. They’re terribly nice, though I was nervous of them initially, the whole process of how you do things. When they asked me to do the ICA thing it sounded great, I really wanted to mess up their stuff. Then I realised that I couldn’t really mess up their stuff so I went to the studio and did loads of recordings. We swapped tracks, and it was a really nice thing to do. I had this lovely loop of them and me for the end of Epic Of The Everest, but it never made it in, but one of the skateboards in the studio made it in. At the ICA they said ‘shall we start really quietly?’ and then they did start and I was all ‘woaaah!’ It’s fun to sing and make noises, and I wish I could leap around a little bit more. I don’t think I’ve got very much stage presence, though there’s a little bit of Gen in there, a little bit of Gristle. They were scary, Throbbing Gristle, the volume! Factory Floor are loud but I love it. Collaborations are really good fun.

Simon Fisher Turner’s soundtrack to The Epic Of Everest is out shortly via Mute records, with a DVD by the BFI. Pre-order the vinyl from Mute here. There is a live soundtrack tomorrow night at Odeon West End Cinema, Leicester Square, London with musicians including Cosey Fanni Tutti, Land Observations and Andrew Blick of Gyratory System. For more information go here