Interviewing Karl O’Connor is just like experiencing one of his DJ sets: pure forward momentum and witty aggression, punctuated by cackles and laughter, and one of the finest ways I can think of to while away an hour and a half.

Last month, Filip Kalinowski spoke to O’Connor, aka Regis, for a more general Quietus interview. This time, we thought we’d put some meat on the bones with a Strange World Of Regis and Downwards feature, delving into his own work over the past ten years and how it fits with this most excellent and diverse of labels, with its austere, stern, packaging. What emerges as a major theme throughout the course of our conversation, looking at his past work and collaborations, is that it’s rather restrictive to view O’Connor as primarily a techno artist. His lineage comes more from the Throbbing Gristle, early Mute, post-punk, Soft Cell and Coil axis – read on to discover how Geoff Rushton, aka Jhon Balance, gave Downwards its name – than anything specifically dancefloor orientated. He explores darker, harder places certainly, and does so with total commitment and integrity, but always with a sense of the playful, even a very British sense of humour.

But before that, let’s limber up with a few choice O’Connor one-twos on pressing issues of the day…

On Downwards’ A&R style: "Downwards has this massive, tempestuous relationship with all the artists. I’ve fallen out with everybody apart from the new artists. Give them time. I’m not allowed to talk to one of [the older artists], his wife has forbidden it; one of them I am convinced tried to assassinate me by tampering with my car. It’s fucking comedy, I couldn’t make it up. It was a complete and utter disaster from beginning to end, but this is the point, this is why it’s interesting. Sometimes I think ‘how the hell is that happening?’ I do have to add that I have made up with most of them."

On clubbing: "’Good times’. That mass togetherness, I wasn’t into that. I wanted to go out, have a bit of a pogo, smash things up. Maybe it’s a generational thing – when I was a kid we’d hang around a phone box because it had a light in it, that was the only entertainment we’d get. It was boring. Much to other people’s disgust, I find it a bit of a pastime, DJing dance music. It’s a bit like golf. People go out – ‘what did you do at the weekend?’ ‘Go clubbing’. It might as well be golf or something. I’ve never really got it, I’ve never understood it. It’s probably just as well."

On myths of acid house: "This is the nonsense about it. These were the blokes who used to beat me up on way home from Fad Gadget concerts, and three years later they’re all ‘Oh yeah ‘I’m into electronic music’. You were into Level 42 fucking three years ago. I think it was people with ponytails and bomber jackets from Ilford, I was massively suspicious. I definitely felt something passing when acid house came along. Electronic music was really sophisticated in the mid 80s, but then it just seemed a bit cheap. Dungarees, men with ponytails, it upset me quite a lot to be honest, that’s why I stayed in for quite a while. I saw Einsturzende Neubauten play at the Astoria, one of the greatest gigs of the year, end of the decade, fantastic; then a few weeks later I saw The Stone Roses, it was the only band I’ve ever walked out of, it was that awful. I thought, well, if that’s the future, you can have it. That really stuck to me, I gave up a lot of stuff along the while. I am stubborn, I am massively judgmental."

On Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds: "I first saw him when they were still Nick Cave & The Cavemen, it was after Rowland S Howard had left, and from that day to this he’s never, ever disappointed me. The records are one thing, they are what they are, but live, it’s not just the experience, it’s the experience of the experience. You’re looking at all of them and thinking ‘Jesus Christ, this is serious’. The Bad Seeds are fucking untouchable."

On techno snobs: "These are the people who were disgruntled because I said something about Kraftwerk [in the last Quietus interview]. All of them are about five, they’ve all got the same records, they’ve got nothing outside of that and they don’t do anything else. These people know more about my music than I do. I don’t have a clue about anything."

On sonic pugilism: "Dance music is a great vehicle for sound pressure. It really did break the DNA of rock music, and that physicality is so important to me. That’s why I like NON and stuff like that, because I want to be assaulted. Does that say a lot about me? Probably."

And so, without further ado, Karl O’Connor guides us through the Strange World Of Regis & Downwards….

White Savage Dance compilation (reissue of early material)

The music I was making was extremely dated. By 1985 I was harking back, I wanted to be Frank Tovey, I wanted to be Soft Cell, but that was a generation away. I had a synth, people say ‘Oh synths were cheap technology’ – it wasn’t, it was £250. The natural thing was to do gigs, you couldn’t make a record, that was just stupid, so most of that stuff was recorded at soundchecks. It was me and a few friends who I roped into it. We had a synth, shared a pair of PVC trousers, and had a smoke machine. If that’s not rock & roll – that’s the only reason I’m in it! We supported a lot of local C86 people like Mighty Mighty and The Capitals, who were ex-Nightingales, stuff like that. But it was 1986, it wasn’t the 70s, so it was just a bit odd really. We recorded, I kept them away, and that was that. It was actually Juan Mendez [Silent Servant] who said ‘You’ve got to put those 7"s out again, there’s a whole new audience of people who love them. They’re just sitting in techno people’s record collections who’ve bought them because they’re on Downwards, and are disgusted.’ So thanks to Juan for that.

Even though it’s completely different to what we’re doing at Downwards, there’s some sort of golden thread. It was more about getting ideas out, most of the early stuff sounds like it was pressed on the back of a digestive biscuit, it was lo-fi and charming, but it wasn’t deliberate. A lot of people have made far more lavish and accomplished productions on much less, it has to be said, but I think it was about getting ideas down, mistakes, being instant. They’re English pop oddities, and I am still proud of them. I think I like that stuff the best actually, I’m never embarrassed of the juvenile, probably because I’m still stuck there, I still think I’m 18. That’s great sometimes, but it does cause problems.

Surgeon – ‘Atol’

I think Tony’s stuff, for the first time ever, it smelled of success. Tony is the only bona fide star in the whole thing. He has a fantastic attitude to everything, he puts up with quite a lot, and it was a leap of faith with me and the label. Although popular wisdom is that we’re quite different, we’re actually very similar in lots of ways.

Mick Harris was central – he’d just left Napalm Death, he’d started Scorn. We became friends because I worked at a record shop, which is where I met Justin [Broadrick, Godflesh, Jesu] and all these other people. It was a great bunch of people at that time, all doing their own thing. Mick said ‘Just come round my house and record stuff’. Mick had a studio set up in his downstairs toilet, and that’s where Tony recorded it. It was all because of Mick Harris, without him there’s no doubt in my mind that, for me or Tony, it wouldn’t have happened. Mick introduced us – he used to go to the House Of God. Mick told Tony, ‘This guy Karl is putting this stuff out’, I heard his stuff, and straight away I thought it was fantastic and straight away it was ‘This is what I want to be doing, this is the future’.

Of course our early records pay a massive homage to Jeff Mills, that’s completely obvious, but what I wanted to do at the time was have a bespoke UK label that had its own artists, that was just a select few people, it was very local. Totally like an old punk label. We’ve never done a contract, we’ve never done a release schedule, our distributors never knew when we were going to do a release, things would just turn up. I was on the dole then. The first 12" came in a Downwards plastic bag with a postcard, and I remember spending £60 getting the postcards done, and thinking ‘Oh shit, I’ve only got £20 for two weeks’. The reality of it was that I’d put out all these records that hadn’t sold, but Tony’s was a combination of everything, it was really raw, it felt very modern, it was very English as well. It wasn’t like what was coming from America, it came out, and we couldn’t stop re-pressing.

A General Rant About Brum

Birmingham. It is what it is. There were so many great bands who came from the city, it’s just we didn’t shout as loud as people from Manchester – but that’s in the nature of the city, and that’s completely fine. It’s an industrial village, really… as Tony Surgeon says, ‘Anything nice or remotely artistic that happens, people either don’t go or burn it down’. But that’s probably why Supersonic works. In Birmingham you had the Au Pairs, the great unsung punk band, The Prefects, and even up to Birdland, they were great for those brief few records they put out, but it’s all been so dislocated. There are a lot of warring factions. The centre of Birmingham was very Quaker-run, so nightclubs and everything found it really hard to get a license – so there wasn’t a club for people to go to until the mid 80s. You had the Rum Runner – the club where Duran Duran came from – which was very glitzy, though it was an amazing club that deserves as much credit as the Hacienda.

It’s provincial England, it’s not London, just get over it and get on with it – and for the most part I think it does. It’s a massive rock city, which meant it was never seen as sophisticated, and that was its problem, but also the great thing about it. It was never a place for electronic music until Network Records, and without Network Records and Neil Rushton there’d be no Detroit, because he went there and did that 10 [Records] compilation and brought them all back. For me personally, it was exciting that there was an electronic label from Birmingham, even if it wasn’t all to my taste.

It can be grim at night, though, they can smell you out – easy meat. I always worked in nightclubs in Birmingham when I was at college, from about 1985. I saw the progression. When house started coming in about ’85, that’s why I was against house music or dance music as it was, it always seemed to appeal to those types of people. I was forever in the coat check and hearing this ‘boom boom boom’, and thinking ‘This is awful’. Plus it was music made for mass consumption, that’s what I thought, until I heard Mills and the acid stuff that Mick used to bring back – then I thought ‘This is music that appeals to me’. But Birmingham wasn’t all doom and gloom. Doom and gloom in Digbeth? Now that’s a shithole.

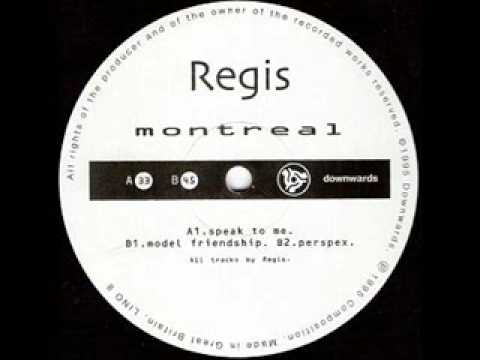

Regis – ‘Montreal’

Tony’s two records were a massive success, so I thought ‘shit’, we can’t just do this. Until the late 90s, people didn’t really know who ran the label. Nobody knew what I looked like, because I didn’t want to be an artist, I just wanted to run the label. I looked at my old DATs which had a few ideas on them, it was a bit like DAF and I’d timed it to some disco.

I didn’t have a clue about BPMs, by the way. Someone called up from Mr C’s label and he asked me ‘What BPM do you work at?’ I said ‘I don’t know, 1000?’ I had no idea. He put the phone down, disgusted. We didn’t have an idea how long a record should be for DJing, we had to ring up Mark P and Baby Ford and ask ‘How long should dance records be?’ It was that naive. So I did ‘Montreal’, I plugged everything in and did it in three hours, probably less. I think that cemented the importance of the label, suddenly it was everywhere and people wanted to know ‘What’s going on here? Something is really happening’. Bigger labels and press started snooping around.

It was big in Germany first, which was great because that was my influence – if the Germans like it, it must be good. Me and Tony were thrown together then. It was very naive, like all our early records. And a lot of it was me wanting to pay tribute to my influences, DAF and Neubauten. Nobody gave a fuck about them in the early 90s. I can completely steal these bastards’ ideas, nobody has heard of them, and it all paid off really.

Regis – Gymnastics album

‘Careless Pedestrian’, from the Gymnastics LP

Did I do an album so people could finally have sex to Regis? Funnily enough, there have been four people who have told me that. It weighs in at about 32 minutes, which probably says a lot about my fans and their sex lives.

It was definitely a Stooges and Suicide thing, where everything sounded very similar, you could tell it was all recorded in the same time period. It’s very raw. I was in the studio with Mick Harris. I used to do my mixes live to tape and this amplifier used to cut out. So every track on the album I had been mixing without being able to hear it, which is why I would always pull back quickly at the end, because I never knew where I was. So that’s why there are little mistakes here and there. At that particular point it was about putting down the ideas as quickly as possible, and getting it out, because we thought that the rich vein of popularity would go at some point, so I had to do an album.

It was taking a lot of my influences, from DAF, and then contemporary stuff like Beltram and Dan Bell, DBX in particular. It was supposed to be a quick, violent, bite-sized punch up. It still works now and sounds relevant in a DJ set, whereas a lot of stuff from that time sounds like you’re playing it as it was a hit at that time, rather than pummeling, punching the shit out of the dancefloor. People would always want to know what the titles were about, ‘The Black Freighter’ or whatever, but that was just Bertolt Brecht, The Threepenny Opera. I think the further we could take liberties with certain things… that’s what gave it strength, the identity, it was just us, we weren’t tapping into the thing of what techno should be. I wanted something that was here and now and understandable, not future or fantastical.

Robert Gorl – Sex Drops LP / Chrislo Haas 12"

Regis & Robert Gorl

I’d known Robert for a year or so, and then Disko B asked me to produce his album. They thought, ‘This is great, a marriage made in heaven, a hero [Gorl was a member of DAF], get a modern slant on it’. What I really wanted to do was get Robert drumming again, but he couldn’t at the time because he’d previously had a really bad car accident, so he wasn’t drumming that much. He’s got every loop he ever created with Conny Plank back in the DAF days, so we went through those and we did it in a week. It was a great experience, pretty eye-opening. Working with Robert made me appreciate Conny Plank even more.

Robert Gorl – ‘Scoops’

At the same time, Marc Snow said ‘Can you help me, Chris Haas has just really offended the studio engineer, told everyone to fuck off and stormed out, but he’s left a deposit on the mixing desk’. Haas had a voice like the bottom of a gravel pit – he was a bear of a man, out of control, from a different era. I did a remix for him, and kept in contact. I remember he phoned me up at my mum’s house and said ‘Regis, Regis, we’re going down to Conny’s studio. FM Einheit is coming too, it’s all arranged. We’re going to bring our wives, and we’re going to fuck’. I thought, presumably their own wives, but yeah, sounds great. Then he said ‘I’ve got to get the singer, I want Busta Rhymes’. I thought, oh my God, he’s lost his fucking mind. "See you soon Chris", and put the phone down. I got to work with my two big heroes.

Tresor 100 Peel Session

John Peel played ‘Speak To Me’ on the radio for the first time. I’d never sent him the record, I don’t know how he got it, it was the proudest moment in my whole life. Then we were asked to do the Tresor Peel Session, and it was the only one in the history of Peel when he was there in the studio with us. It was the most magical night ever. Tony Surgeon could have played a set of techno classics, but he didn’t, he played an ambient set. I was really worried about how I would sound, but the BBC really do have this machine that makes everything sound amazing. Peel came up to me afterwards and said ‘That was great Karl’.

For one brief second you’ve got Peel’s ear, in the same way Gene Vincent got his ear, or The Smiths, or Joy Division. Whenever he was in Birmingham doing something he’d try and get me or Tony on, and he’s always been a big supporter of Birmingham music. I think Mick Harris has got the most sessions after Mark E Smith. For a long time after Peel died I didn’t feel that there was any point in making music – John Peel dying was that important to me personally. I thought ‘What’s the point?’ I always judge music post-Peel’s death. ‘You haven’t been filtered mate’. A lot of music isn’t legit because it hasn’t been blessed. I’ll always hold the night of that session fondly, because it was the night I was almost legit.

British Murder Boys – ‘Learn Your Lesson’ 12"

British Murder Boys, photographed by Brian Griffen

The name of BMB was sorted when Surgeon mentioned to Sleazy [Peter Christopherson of TG and Coil] that we were called British Murder Boys. Sleazy went ‘Ooh, I really like that’, so we thought ‘We’re having that’. Sleazy and Geoff were a massive part of Downwards. Mick drummed on Backwards in 1993, and I went down with him to Swan Yard studios, Danny Hyde was there. The studio was fucking expensive, and that was basically the project that put World Serpent out of business. Five hours later Geoff comes in, and Danny said ‘What’s wrong, where’ve you been?’ Geoff said ‘It’s all going downwards, it’s all going downwards’, and it stuck in my mind. Then he went into the booth and started singing ‘Make Room For The Mushrooms’. Later, Peter invited me and Tony down to Milton Keynes, something very uncertain, but we couldn’t do it, which is obviously a massive regret. So Sleazy was very into the British Murder Boys name.

British Murder Boys live

I think ‘Learn Your Lesson’ was the last record both of us actually did in Birmingham, so it was symbolic for that. It was the last record we did on equipment through a desk. It’s my favourite British Murder Boys record. ‘Learn Your Lesson’ was basically us putting Whitehouse onto the dancefloor, and that was great because all of a sudden you’ve got all these kids going ‘Can you play ‘Wriggle Like An Eel’? That’s when I realised, ‘Shit, kids are into good music, not into this bongo loop, really pedestrian tech house rubbish’. That was music for hairdressers, very sanitised and very safe. When me and Tony came together, people were expecting linear techno, so we were being contrary again. But it was picking up the baton, the thread that goes back to the Cabs and whatever, and it’s great to be able to do that.

Regis on the Blackest Ever Black label

The world doesn’t need another Regis record, that’s for sure. But it was this great jump in generations. When I met Kiran [Sande] of Blackest Ever Black, I thought ‘These are the people I wanted to meet ten years ago, but they weren’t there’. I feel really proud of working with Kiran, because I wanted to redo it. When you do things for long enough you can be a bit contrary, I didn’t have to make music to get gigs or get profile, and the timing was completely correct. I felt there was a space for me to occupy. It’s all very well being out on a limb – that’s what it was with the British Murder Boys, the timing was completely wrong for making that kind of music, it was the start of minimal, so for us doing that was hard, and we ended up confusing everybody, even our staunchest fans started to hate it.

I felt [with the BEB material] I could pick up where I left off. I wanted to not make 4/4 music, which quite frankly at that moment I didn’t feel I could expand upon anything I’d done previously, so it was pointless. With digital technology anything is playable now, because you can chop it up, digitise it, beatmap it, which is fantastic for artists. If record sales are down as well, surely people have to go and make brave attempts? It’s telling that people don’t do that, it’s telling about their motivation for making music in the first place. You can tell when people are making music from a totally artistically bankrupt place.

British Murder Boys live in Tokyo, Japan 2013

We did a DJ set at the Blackest Ever Black night, we talked at length and decided that we were really just doing what we’d been doing before. So we decided to do one last blowout, be completely indulgent for just one night. Where can we get away with it? Japan! Perfect.

Our promoter out there – she only promotes us and Saxon – said ‘Brilliant’. We played a lot of unreleased stuff, we had microphones, guitars, heavy incense, people dressed in costumes from a Catholic church in Spain. We had to get them signed off by a priest. An odd thing happened – even though we had planned what we were doing I started feeling really light-headed, [and] Tony went mental. It was the first time ever I’ve seen Tony have a really really primal reaction. It was everything we’d ever wanted to do, distilled in one evening: it was commercial suicide, it was unsatisfactory to our fans, people loved it and hated it, they didn’t know what they’d just seen. Afterwards it was quite funny, me and Tony got offstage and, like the cliché, hugged each other. We were emotionally drained, it was such an intense thing, absolute destruction, a night of wrongness.

Thanks to Karl O’Connor for the accompanying photos.

The compilation celebrating two decades of Downwards – Halha: 20 Years Of Downwards – is out now, featuring new and old music from Regis, Surgeon, Antonym, Samuel Kerridge, OAKE, Mick Harris, Sleeparchive and more.