Photograph courtesy of Chad Kamenshine

The front cover for of Montreal’s 2008 album Hissing Fauna, Are You The Destroyer? contains a bright kaleidoscopic pattern being engulfed by two black semi-circles, creating an image that perfectly captures the dichotomy within the music. Darkness pushing against vibrancy. Solid blocks of bleak versus ecstatic effervescence. It really looks like the sound of the album, and represents the sound of the band as a whole pretty well. Over the course of 13 albums in 19 years, from indie folk to vaudevillian theatrics and into glam and funk via atonal electronics and dense orchestration, of Montreal have twisted and splintered into many different shapes, a range of colours in vast gradients of warm lysergic sunshine to abyssal dark.

Although many band members and collaborators have contributed to this colourful musical spectrum on record, of Montreal has always really been the brainchild of Kevin Barnes, especially during the prolific run of albums between 2004 and 2013 where the confessional nature of the material was like listening to Barnes’ inner monologue, an intensely groundbreaking personal psychoanalysis. I almost feel like I know more about what happened in Barnes’ life in that decade than I do my own family’s. I’ve spent a lot of that time mostly listening to of Montreal, and a lot of that time growing and understanding about my own desires, perversions and darknesses through the filter of Barnes’ very introspective work. Therein lies why I would consider of Montreal to be my favourite band: that the work may be the product of an individual – and the work concerns the happenings of that individual to such a huge degree – but the depth of the work created allows you as a listener to position yourself within it and use it for your own explorations.

It’s important to consider the two very different spaces that of Montreal operate within though. The live experience is really a markedly different beast to the recorded output, shifting the introspection into a bizarre celebration between a fanatic audience and the band who have consisted of a large and rotating group of musicians helping to embody the soundtrack to the blissfully chromatic collapse heard on the records. They provide an ecstatic counterpoint to the deeply solo experience of listening to the albums. Still, whether on or off stage, Barnes has remained at the helm and he has often sacrificed his personal relationships for the sake of his art succeeding. He’d be nowhere without the supporting cast, but this is really a story about Kevin.

Cherry Peel To Aldhils Arboretum

I find it impossible to be a purist about of Montreal, as every fan or ex-fan will have their own entry and exit points. My golden age is someone else’s shit sandwich, and vice versa. You’ll have to forgive me – especially if you are looking for a comprehensive history – for condensing the first five LPs of the band’s early development to merely one section of this piece, but the truth is it’s not the period of the band that I came in on. That’s not to say that there aren’t hints at brilliance and pockets of intrigue here though.

The initial two albums: Cherry Peel and The Bedside Drama: A Petite Tragedy feature Derek Almstead on drums and Bryan Poole on bass and backing vocals, and are unashamedly twee indie folk records. On a 2013 Reddit AMA with Barnes, he said this early material was unlikely to make a reappearance in live sets in the future unless they were ‘touring kindergartens’. While most of the peripheral ingredients that would make of Montreal one of the most singular bands in the last 20 years were yet to surface, these early albums at least introduced Barnes as a very prolific songwriter and astute performer, skills that were refined in the fine company of the now legendary Elephant 6 collective in Athens, GA.

Coquelicot Asleep In The Poppies: A Variety Of Whimsical Verse, the band’s conceptual fourth LP, stands as the most assured example of the future of Montreal sound: Barnes’ immaculate self-harmonisation and vocal elasticity, the distinctively woody and melodic bass lines (Almstead now on bass) that would later become a lead instrument in itself, and not to mention the occasional sudden mid-song shift in structure or style that would assume an almost overbearing presence in later albums. Both Coquelicot and Aldhils Arboretum displayed a much more refined sound and exhibited an increasingly theatrical, vaudevillian aspect to Barnes’ character based songs.

According to the excellent crowdfunded 2014 documentary The Past Is A Grotesque Animal, this period of the band featured all members living under one roof and thus planted the initial seeds of a family affair mentality that would continue, at least on the road, for years to come. Dottie Alexander on keys, James Huggins on drums, as well as Kevin’s brother David who had contributed his artwork to the cover of 1999’s The Gay Parade. It was within the tours of this period that Barnes would also meet his future wife, Norwegian artist and musician Nina Grøttland, who would join the band on bass after Amsted’s departure, and with whom Barnes would eventually move out of the band lodgings with, a move that would change the dynamic and sound of the group forever.

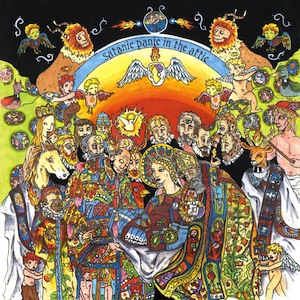

Satanic Panic In The Attic

I’ve always admired Kevin Barnes’ ability to kickstart an album, and how this dedication to the structure of that format has made him one of the greatest artists working in that medium. With this new era of the band, ushered in to resemble more of a solo recording project, there had to be a real confidence in the work for Barnes to carry what this band had built as a collaborative unit on his own shoulders. ‘Disconnect The Dots’ crashes this age into focus and for the first time we’re really seeing the breadth of Barnes’ vision. Recorded entirely at home by Barnes himself, including each part of the drum kit recorded separately for the best fidelity his home studio could give him, Satanic Panic In The Attic began to experiment with a wider array of recording techniques and sounds, not least the prominence of drum machines and synthesisers which, for a lo-fi indie band of their ilk at the time, was a bold stride. Satanic Panic is so much more robust than its predecessors in just about every way that you have to wonder how severely Barnes felt held back by compromising and relinquishing his control over the arrangements and production for so long before it. Barnes narrowly pre-dates the now commonplace trend of the at-home self-producing songwriter and here he sets an incredible example for others to follow.

Satanic Panic would prove to be the breakthrough album for of Montreal and their first on the Polyvinyl Records label, a relationship which continues steadfastly to this day. It was critically well received and it was a huge artistic and personal leap for Barnes. Bryan Poole would return on guitar for touring in promotion of this album, though it became a tour defined by Nina Barnes becoming pregnant with the couple’s child Alabee, the arrival of whom would introduce the next significant sea change in the band’s career.

The Sunlandic Twins

The lyrical content of Satanic Panic and The Sunlandic Twins started to assume a darker and more personal edge than its predecessors, but where Satanic Panic often basked in the fiery glow of Barnes’ fresh and frenzied marriage to Nina (the partnership of which is depicted on the album cover of Sunlandic), The Sunlandic Twins was written amidst the couple’s uprooting to Nina’s native Norway for the birth of their child and the uncertain future of the band now that the concerns of family were placed at the forefront of responsibility. Somewhat unexpectedly becoming a father and moving to a cold winter climate where the light never really reaches beyond a certain low point of brightness helped swerve Barnes into a severe postpartum depression. The sound of the album split into two halves, the first a more frantic breakdown where Barnes manically rejoices while his psyche crumbles around him (‘Forecast Fascist Future’), and the second veiled by a heavy mist (‘Death Of A Shade Of A Hue’), the songs bleaker and more despondent than any previous.

Side one of The Sunlandic Twins

Side two of The Sunlandic Twins

It would be another commercial and critical milestone for the group and the resulting tour was one of complete and apparently much-needed release from Barnes’ domestic responsibilities. Drenched in glitter, heavy with glam, androgynous costume changes and boundless expression. The band’s popularity soared. While Nina and a young Alabee were on the tour (bass now being handled by Matt Dawson) tensions rose between the couple as Barnes seemed unable to reconcile the success and freedom that the tour gave him with the family environment where he had so recently been depressed. Nina departed, Alabee in tow, back to Norway without Kevin.

Hissing Fauna, Are You The Destroyer? Part One

It’s 2007 and I am a boy who spends most of his time writing and recording songs for bands that fail quickly. The pains of love or lack thereof are felt very intensely at this age. I am not at all in touch with my sexuality, it proves a terrifying prospect with nothing and no one to help define it. I either have some undiagnosed anxiety and depression disorder or I’m just having a really bad time being a teenager, or both. Bizarrely, I know exactly what I want to do with my life but I have little to no idea of how to achieve it. I don’t have direction. I’m an average student at best who finds no encouragement for his desired career from the academic world. Most of the bands I devoted my life to being a fan of over the year or two previous have started to wear on me and overall I need a change. I need something to identify with, to call my own.

It’s been two weeks since the release of Hissing Fauna, Are You The Destroyer? and a new acquaintance I meet through the local Southampton music scene works in a local branch of Fopp and is adamant that I give of Montreal a listen. How did he know?

The next phase of my life begins immediately upon hearing the sampled baby and the synthesised drum fill shellacking me into the first verse. I recoil at the garishness of it all. The album is much more colourful and bizarre than anything I’ve listened to at this point in my life, and I’m frightened by that. But I’m also liberated by it. The way the unabashed pop and blooming hooks belie the sheer darkness and candour of the lyrics takes many listens for me to unravel, and when I finally do, I have to double-take. What is happening?

The first half ripples with quick-fire pop hits, namely ‘Heimdalsgate Like A Promethean Curse’ which characterises Barnes’ depression as a chemical imbalance that he pleads with not to dampen his creativity and ruin his life, and ‘Gronlandic Edit’ in which Barnes leads a reclusive Norwegian existence: ‘Daytime I’m so absent minded / night time meeting new anxieties / so am I erasing myself? / Hope I’m not erasing myself.’

The second half moves into a sassy, swaggering funk territory, but bristles with a relentlessly dark energy that could snap its author at any moment (‘How you wanna hate a thing when I am so superior? / How you wanna tag my style when you so inferior?’) Barnes audibly wrestles with the two sides of his character in a freakish Jekyll & Hyde funk experience on the album’s home stretch.

The album is a long corridor and I have the key to every door on it. It’ll take serious time to explore each one but I want to know everything about of Montreal. They’re mine now.

The Past Is A Grotesque Animal

So far we’ve not settled on anything for too long before tumbling into a new verse or chord change, we’ve explored but we’ve not yet dwelled, we’ve scoured but we’ve not yet thoroughly examined. But this time it’s going to be four chords and one beat over 12 minutes, and we’re going to get some shit out in the open. It’s not going to be a comfortable ride. There’s no sugary hooks or melodic bass lines or chiming anythings. There’s sweet fuck all. There’s nothing to cling onto and no structural trap door to fall out through into fresh melodic relief. There’s only unadulterated motorik quicksand, caterwauling harmonics and you versus your own disintegration.

Throw it all in my face, I don’t care.

It doesn’t even matter what it is you want to tune into or face up to, Barnes has left you with all the right intonations to climb, all the right words for you to howl along to, and left pauses for breath in all the right places. It doesn’t have to be about Nina or Alabee or Norway or chemical depression or anything. The spotlight’s on you now, and this is about expression, about transformation, because you need to do those things and you need to do them now. In transit or at home. With chemicals or in stone cold sobriety. Alone or in congregation. Catharsis for all.

No matter where we are, we’re always touching by underground wires.

Skeletal Lamping / Georgie Fruit

Spurred on by the reception to Hissing Fauna and reuniting with Nina just before that album’s release, Barnes was arguably in a better mental state with which to approach Skeletal Lamping, not that listening to the resulting record will necessarily do anything to confirm that. Skeletal Lamping is one of the most ambitious albums to have ever come from a band who originated in the indie pop universe. Over the course of the 15 tracks, conventional song structure is completely thrown out of the window in favour of a strobing pulse of whirlwind structural changes where most singular tracks actually contain about three or four wildly different songs within them.

Barnes says that the album was his attempt to bring all of his “puzzling, contradicting, disturbing, humorous fantasies, ruminations and observations to the surface” so that he could understand the reason for them being in his head, and this at least goes some way to explaining the schizophrenia of the flow. However, perhaps the best explanation lies in the fact that Barnes spends most of the album switching between his own first person and assuming the role of an alter-ego named Georgie Fruit, an African American in his mid 40s who has been through multiple sex changes and who used to play in an Ohio Players-style Funk Rock band called Arousal. Becoming a character was probably a useful way to explain the sudden dedication Barnes had to laying the funk down after initially setting up his stall trading in saccharine twee-folk. Conceptual distance or not though, as listeners we’re still ultimately dealing with Barnes’ inner turbulence.

Perhaps due to the unstable nature of Skeletal Lamping, it would be where the partial backlash began, at least from a critical standpoint. Reviews from this point on would become decidedly more mixed than the last few albums as the Georgie Fruit saga would continue into the following LP False Priest and the short but substantial EP thecontrollorsphere (where it’s almost as if we hear the exorcism of Fruit within the first track). Reviews are something that Barnes would take to heart and even publicly respond to on occasion, an inadvisable move for some perhaps, but one that only strengthened the view of Barnes as an artist of a resolutely uncompromising nature.

The tour for Skeletal Lamping would also become the high watermark – at least in terms of its excess and ambition – for the live experience of the band, featuring scenes – among myriad others – such as Barnes rising from a coffin that was full with shaving foam, simulating his own hanging, forceful drug taking and masked orgy simulations, pig heads and parrot prisoners, and most memorably a show in New York’s Roseland Ballroom where Barnes rode onto stage on a white horse while singing Skeletal’s slow-jam highlight ‘St Exquisite’s Confessions’ (“I’m so sick of sucking the dick of this cruel, cruel city”).

The experimental structure of the music and the sheer difficulty of wading through it as a whole lends to a theory that Skeletal Lamping is essentially pop music’s Finnegans Wake, largely unheard in full by the general public. It’s a wholly disorientating, terrifying, hilarious and euphoric experience, and for my money it’s absolutely fucking brilliant.

David Barnes

Kevin’s brother David Barnes first contributed his artwork to of Montreal with the cover of the band’s third LP The Gay Parade, and by the time of Satanic Panic he would be integral in expanding the deep wilderness of his brother’s music into a dense visual package for the rest of the band’s career. It’s really quite something when scrolling through your music library to hit upon the of Montreal section, and for a few consecutive lines there is a flash of busy chroma unlike the records that sit around them. Satanic Panic In The Attic is a psychedelic play on El Greco’s ’The Burial Of The Count Of Orgaz’ (1586), and it does well in introducing that burgeoning creative period of the band as much as the music itself does.

The packaging and multiple format release of Skeletal Lamping, too, is one of the most innovative and creative I’ve ever experienced. The CD version unfolds into a great psychosexual jungle and refolds into a many-toothed, overgrown monster of a desk ornament, while the insert of the vinyl version was a large fold-out horse specifically for wall mounting. This was truly the peak of my obsession with of Montreal and for there to be such a strong visual and physical element that I could display so proudly was a very important thing for me as a fan. I’ve never since experienced anything like it, and something about the presence of these relics has ensured my long time fanaticism. It would be the last time in my young life that band memorabilia would be given pride of place on my wall as I lay there on my bed staring at these objects and delving deep into of Montreal’s frightening but life affirming world.

Paralytic Stalks

The last time it felt like of Montreal most accurately slotted its deformed puzzle piece into the jigsaw of my life was with the release of Paralytic Stalks. I found 2010’s False Priest to be an enjoyable romp of an album but it failed to really ignite my interest at the time, despite the high regard I now hold it in retrospectively. When turmoil ensued for me in the dawn of 2012, almost on-cue Paralytic Stalks was released to help me along into a most transformative year of my life. These periods of drifting in and out of hysteria with your favourite bands, especially ones that are so defined by their hysteric nature, only enhance your love when they come back swooping into your life at a time of need.

Despite the mammoth misunderstanding of Skeletal Lamping, and the very accurate legacy of Hissing Fauna, it seems Paralytic Stalks is forever to be the forgotten classic of the of Montreal catalogue. It’s both as challenging and accessible as the aforementioned and it serves as a fitting coda to Barnes’ solo studio masterpieces. It is also by far the best sounding record Barnes has ever produced, his knowledge of fidelity increased ten-fold since collaborating with expert producer and composer Jon Brion on the previous album. In many ways Paralytic Stalks acts as a stylistic and thematic curtain call, and performs an encore of jarring funk, deeply confessional lyricism and Penderecki influenced atonal string sections. Most songs seem hellbent on passing through severe dissonance to arrive at sudden perfect cadences as though Barnes is trying to resolve something once and for all.

Lousy With Sylvianbriar/Aureate Gloom

It’s telling that the album cover of 2013’s lousy with sylvianbriar was a world away from David Barnes’ usual limb disembodiment terror fest, instead featuring a simpler three dimensional image of a glistening motorcycle by Nina. Barnes would write this album on a west coast songwriting sabbatical and ultimately decide to record it mostly live with an entirely new band (save for the excellent sticksmanship of Clayton Rychlik who had been with of Montreal since 2010). Not so much a return to roots but certainly a hark back to the simpler band-led arrangements of early of Montreal albums, there is a tenderness to the songwriting and a great deal of focus to the craft.

But the thing with sylvianbriar was that the manic energy and boundless experimentation of the music was not in the foreground any longer. For the first time in years it felt like you were able to relate of Montreal’s sound to other artists and place it in a context that existed outside its own world, something which I’ve often found it difficult to do when talking about the four or five albums that precede it. Ultimately though, I don’t think continually making Skeletal Lamping is a sustainable way for its creator to stabilise an already erratic mental makeup for the sake of his audience’s morbid fascination with his breakdown and the validation they feel for their own through that.

With 2015’s Aureate Gloom – an album that returned somewhat to funky, angular guitar sounds via the filter of late 1970s New York post punk – I was lucky enough to catch the band playing at a very sweaty SXSW show in Austin, Texas where I was also performing on the bill. My love reignited for the band on that day, where the band featured a new set of musicians since the last time I had seen them play in 2012. Here I was finally able to dissect the arrangements of this much more snarling and embittered album as I screamed and jumped along with the rest of the crowd. I realised then that this was an experience I hold only for this band, and that the pendulum of my fandom would only continue swinging in great extremes.

Of Montreal play London’s Convergence Festival on 14th March 2016. For tickets and information please visit the festival website