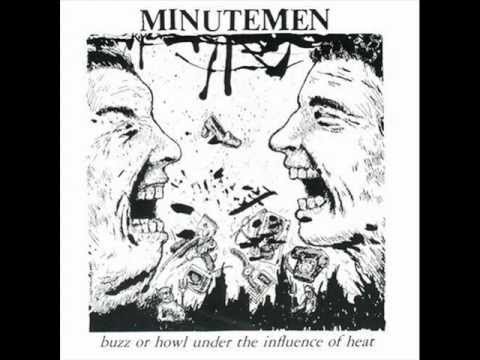

From 1983’s Buzz Or Howl Under The Influence, the Minutemen’s ‘The Product’ was the most philosophically sophisticated bit of art-punk since Pere Ube ignited Ohio. Under its chewed-tape veneer swirled a glut of ideas, insinuations and conflicts.

It was a free jazz haiku on the postmodern condition. It carried the physics of existential rictus. It was a dissonant affront on (and the sound of) the sickness of mediocrity, of complacency. It was flitting-eyed psychodrama. ‘The Product’ was the noise in Albert Camus’ head when he wrote, "The absurd is the essential concept and the first truth." It was also a Reds-punk throwback to intelligentsia post-punk, hyperventilating within, before ultimately conquering, the crushing anxiety that every thought we have is ‘the product’ of capitalist indoctrination – preordained, preprogrammed, part of their plan. "This is an original" it said, "this one is OURS". ‘The Product’ was all this, in the space of just under three minutes. About three minutes later, further on down the LP, Dennes ‘D’ Boon is shouting down the microphone "Big blow jobs!" chuckling and arguing with bassist Mike Watt about his timing.

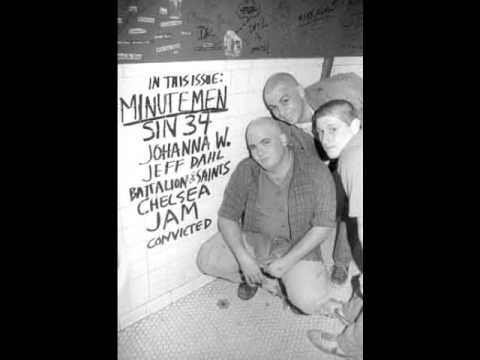

Was there ever a more paradoxical band than the Minutemen? Comprising D. Boon, Mike Watt and drummer George Hurley, natives of working class seaport San Pedro, card-carrying socialists, unpretentious to a fault, and forever jocular, the Minutemen were alt-rock’s most blue-collar act; the union heavies of the 80s underground. Anomalous in the history of working class American hardcore, however, they were also stupendously avant garde. If you didn’t know any better, it was the sound of an affectless dozen or so smacked-up jazz geniuses, deconstructing Gram Parsons via John Coltrane, in a performance art space in no wave-era SoHo. But no, it was work of three good ol’ boys with big ambitions, audacious songs and endless resources of energy.

“Our band could be your life,” they believed. And for many, it was.

The sons of Navy men, immigrants and machinists, the trio believed in hard work, playing cheap gigs, modest living, plain attire, San Pedro and the American Dream. Boon and Watt had as much to say on proletariat hardship as their guttersnipe peers in hardcore. However, aside from the odd catchword thrown in for good measure, lyrically they instead chose a Wire-indebted approach, favouring abstraction over the prosaic, literalist approach taken by their punk brethren. Their agile, hyperkinetic songs, most between one and two minutes long, were populated with twisted syntax, collage, and dislocated poetry. On top of this, although never arch or knowing, the Minutemen would often err towards Wire’s cold conceptualism. However, in another of their paradoxes, they offset this calculated, artsy objectivity with an intense moralism, an undying compassion for the disenfranchised and, most keenly, the complete absence of cynicism. The music is contagiously uncynical: rent with the joy of empowerment, a childlike naivety (Boon’s lyrics often centred around an image of the Minutemen as “child soldiers” of The Cause) and beneath it all, what you might define as love.

Rarely had there been an avant garde music with such a big heart; and this can be credited to the fraternal bond between Watt and Boon forming the soul of the band. Celebrated in punk circles ever since, their mythic friendship can be felt on the moving ‘Anchor’ and more keenly on ‘History Lesson – Part 2’, the Minutemen’s origin story and inspiration for the title of Michael Azarrad’s secret history of alt-rock, Our Band Could Be Your Life. (The actual story is of how, as kids, Boon and Watt met, is fairytale-like as the former dropped out of a tree in front of the latter). As a tonic to back-biting Gallaghers, their unique relationship reveals something profound about the beauty of being in a band with your friends: the solace in one another, the shared troubles, the defiance in the face of indifference, the sense of kinship, the arguments. If you listen closely to the Minutemen, the impression is always of a band who are playing to each other, for each other.

It’s difficult not to view the Minutemen through the prism of Boon and Watt’s relationship. So heartening, touching and true was their friendship – somewhat iconic of the mutual caring that permeates punk communities – it has a way of defining your understanding of the trio. When, in 2009, Fluke fanzine asked Watt how he wanted to be remembered, he answered simply, “As D. Boon’s bass-player."

In strictly musical terms however, accessing the band from the perspective of Boon and Watt’s relationship is key. As RHCP’s Flea asserted, “The Minutemen were so unique… and it’s impossible for something like that to come about if you aren’t D. Boon and Mike Watt, growing up together since they were little kids.” There ran the suggestion that the almost fantastical, highly esoteric music they produced was merely an extension of the weird private world Boon and Watt shared. They had been left to their own devices as high school’s ostracised punk kids. When, after years of friendship, it came time to convey that private world, so detailed was their self-constructed fantasia – overflowing with in-jokes, creeds, arcana and the reams of political text – the result was impenetrable and intricate. The music was exhausting in its attempt to expel every last mote of thought. Watt recounted, “Us Minutemen were insular, man. A lot of the things were kept way inside us… and never really got out." They were permanent residents of this semi-simulated world, as was how they liked it. The Minutemen’s augmented San Pedro, or the real San Pedro? There was no contest. Their story is dedication to the ability for art, or the imagination, or the desire to learn… to change your perception of the world, for the better.

Like the Pixies, the trio were ordinary kids who just happened to make a decidedly unordinary sound: a proto post-hardcore melee which placed them side-by-side with Black Flag and Hüsker Dü as alt-rock’s ‘Big Bang’ bands. But although the Minutemen were ‘punk’ – insofar as their DIY (or ‘Econo’) practices, speed, and anti-establishment outlook were concerned – the trio rejected hardcore as a new orthodoxy, instead privileging CCR, Beefheart, and Blue Oyster Cult over The Ramones continuum. With the unfettered diversity of their influences, they made cornucopian, kaleidoscopic jukebox records resembling 500-channel cable viewing, sometimes completing a record in under a fortnight, as was the case with 43-track double album, Double Nickels On The Dime.

They interpreted the punk idea simplistically. Punk was freedom. The freedom to include anything that was to their personal tastes, the freedom to take their songs, without warning, in whichever direction they pleased. (Without the Minutemen, there would have been no Fugazi.) As Azarrad wrote: “The freedom of the working class man to have culture in his life." But when it came down to it, freedom to them was the birth of a new idea, be it political or musical; the zip-flash moment of genesis. Indeed, the rendering of an (often minuscule) mental object – be it in the form of word, or a single note – was of greater importance to them than its development, its context or its life expectancy. Ideas that resembled the secret slang vocabulary of longtime childhood friends. Their omnivorous pursuit of new ideas seemed to materialise in a type of blissful anxiety. A song would fall over itself in chase of the next Eureka! moment.

Rather than a linear battering ram for the delivery of ‘Eat The Rich’-esque sloganeering, the Minutemen also took punk to mean a florid, omnidirectional expression of self: an infinitely more political act than the aggro content that defined trad hardcore. Artistic expression was a Marxist right, and “a way to learn about the beauty of the world” as Boon asserted in Minutemen documentary, We Jam Econo.

Like Suicide, they were the weirdos within a sea of weirdos. Yet, despite having more cause to be disaffected than many of their peers – as misfits in an already marginalised community – miraculously they displayed none of the alienation angst that, ironically, would come to define the scene they helped create. As Thurston Moore said, “There was nothing of that agony."

But there was paradox right at the root of the Minutemen. Boon and Watt, like the most dogmatic of post-punk artists, obsessed over keeping themselves ‘ideologically sound’ – two sides of the one brain keeping the other in ethical check… taut and discipled, self-regulated. And so it was with their music. Although recorded ‘Econo’-style – i.e. with the barest of means – next to the majority of hardcore pressings the recordings are invariably pristine. Their trick was the ideologically sound division of labour that dictated their set up: a paradox between Boon’s trebly guitar, covering the upper reaches of the high end, and Watts’ bouldering bass, at the reverberating low end, resulting in recordings that were distinct and austere, which in turn allowed for hyperactivity. What is more, the songs retain their clarity in the face of George Hurley’s cacophonous funk and jazz-informed rhythms. Such was the degree of ‘aural real estate’ opened up by Boone and Watt’s ‘political agreement’, the drummer’s flailing, irrepressibly inventive percussion is never intrusive. Aided further by Boone’s distaste for distortion and Hurley’s spry, top-heavy methodology, the overall effect is something like perfection. The way the band fitted around each other was divine.

Michael Azerrad once wrote of the trio: “[They] did it in a direct, intimate way that flattered the intelligence as well as the soul.” Azerrad’s sentiment is echoed by, again, Albert Camus (the man knew his punk), and his thoughts on rebellion, equally descriptive of the Minutemen experience: “Every act of rebellion expresses a nostalgia for innocence and an appeal to the essence of being.” Or as D Boone put it: “Big blow jobs!”

Selected from a pool of some 250 released tracks, recorded over a period of just six years, the following ten songs are testimony to the once liberated, organic spirit of alt-rock, and to Dennes ‘D’ Boone, who died in a car crash in 1985, aged 27.

‘Paranoid Chant’ from Paranoid Time EP (1980)

We’ve all been there, right? You’re trying to talk to girls, only… dammit… you just can’t stop thinking about World War Three. She’s cute… she’s diggin it… but wait… what about “RUSSIA! RUSSIA!” What about those “WARHEADS! WARHEADS!”

Further evidence that elastic post-punk is the ideal setting for contemplating your own mortality, ‘Paranoid Chant’ glows with terrible thoughts, Boon’s mania synching perfectly with his guitar’s two-note siren peals. The warning systems are sounding and all those “miles of stats and figures” are only aggravating his condition.

That the then raging, gloom-stricken SST chose to follow Damaged with Minutemen debut Paranoid Time – only the label’s second release; playful where Black Flag’s debut was deathly – is a credit to the nihilistic power of the Minutemen’s punk-funk snap, at its funniest and most tensile on ‘Paranoid Chant’. Damaged may have been monstrous but the electric sting of nascent Minutemen was every bit as unsettling.

‘Cut’ from Buzz Or Howl Under The Influence (1983)

Sounding like a two-way tie between This Heat’s ‘S.P.Q.R’ and county rock, the aptly named ‘Cut’ is both cutting and structurally jagged. The concision displays shades of a Wire-like experiment in process, with the trio – over Watt’s four lines of self-reflexive iconography – hewing their dynamics down into off-balancing blocks of differing motion; cute without the ‘e’.

In true Minutemen style, however, the aloof conceptualism plays opposite a visceral passion. The punctuating scream of “Cut!” is at once a tiny dadaist play on form and fully punk cathartic. To boot, without comprising the minimalism they manage to fit in not one, but two ass-kicking guitar solos. ‘Cut’ is musically intelligent punk.

‘Ack Ack Ack’ (live) from The Politics Of Time (1984)

At only 40 seconds long, anti-war songs don’t come more to-the-point than ‘Ack Ack Ack’.

The onomatopoeic refrain, used in comic books to represent machine-gun fire, reflects the violence of war, while the lunatic pacing (driven by militant snare) simulates the surge of anarchy and insanity on the battlefield.

But it’s the brevity of the song which is most crucial. It renders ‘Ack Ack Ack’ vaguely absurdist, thus putting it in roughly the same arena as, what was then, a new form of anti-war songwriting, emerging in Britain in the early 80s. A product of post-punk, it was a sensibility which, observed on ‘Enola Gay’ or Killing Joke’s ‘Wardance’, had nothing to with Joan Baez and everything to do with a sense of illogical cruelty – a theme that permeates the satire of screenwriter John Milius. Somehow, Milius lines like “They train young men to drop fire on people, but their commanders won’t allow them to write “fuck” on their bombs because it’s obscene!” are reflected back over the course of ‘Ack Ack Ack’s crazed 40 seconds. From between the cracks of its demented thrash, oozes the greed-induced madness of America’s foolhardy warmongers.

As well as being four minutes less tedious than ‘Give Peace A Chance’ ‘Ack Ack Ack”s shorthand nature rendered it instant and unmistakable, like a graphic war image; demonstrating further their nous with impressionistic politicking. It was also pretty vicious punk song, in case you were in any doubt the Minutemen could greebo-punk with the best of them.

‘This Ain’t No Picnic’ from Double Nickels On The Dime (1984)

One of their most accessible outings (boasting a singalong chorus and hook-y guitar work) ‘This Ain’t No Picnic’ sees the Minutemen at their most post-punk, feeding Gang Of Four through funkadelica and shout-y LA punk.

Boon wrote the song about his racist boss, who banned the listening of jazz and funk radio stations on account of the “n*gger shit” they played. Boon, however, kept the job, because he needed the money. So while ‘This Ain’t No Picnic’ is defiant, angry and frustrated, infused with the “agony” of tolerating his boss there is also a (typically post-punk) undercurrent of shame; for choosing the money over his principles. The tang of self-betrayal resonates the song, ingrained in the harsh tones and Boon’s anxious vocals.

An early predecessor to the ‘alt-rock comedy video’, the song’s promo featured footage of Reagan taken from an old war film. With Ronald looking roughly as bonkers as he did during his presidency, the then-commander-in-chief pilots a bomber over the heads of the band, until serenely dropping his load and blowing Boon & the boys to bits. Costing an estimated $800 to make, it was nominated for an MTV Video Music Award, ultimately losing out to Kajagoogoo’s ‘Too Shy’.

‘The Anchor’ from What Makes A Man Start Fires?(1982)

Opening with the line, “I made a dream last night”, ‘The Anchor’ recalls the Pixies, in the Bostonians’ ability to imbue surreality with an ethereal air, while rendering the final outcome oddly touching. Carried through the clouds by Watt’s coltish bass line, the Minutemen’s first song to clock in at over two minutes long was both their sweetest and most pop.

D. Boon is at peace. He has ‘made’ a dream (creating, even in his sleep). In his dream, he can feel the wind blowing in his face. He’s naked as a newborn. Five beautiful girls surround him: “I was so damn bad” he grins. But wake up D, the anchor is dragging. Always dragging. He has miles to go before he sleeps, is the final implication.

The Minutemen doing melancholy was effecting enough at it was. But in light of Boon’s tragic passing, just three years after ‘The Anchor’ was written, the song holds extra poignancy; a premonition of the big sleep to come.

‘Self-Referenced’ from Buzz Or Howl Under The Influence (1983)

They did punk with a jazz twist, and jazz with a punk twist, but on ‘Self-Referenced’ the two components were weighted equally, resulting in a seamless concoction of taut jazz flex and satisfying wrath.

Kicking off what was arguably their finest EP, ‘Self-Referenced’ stutters with frustrated energy. Boon’s scratchy guitar synchs with Watt’s preposterous jazz bassline, while Hurley showers rapid-fire broken-time around the periphery. They slam into a dinging breakdown – both dissonant and woozily pretty – giving way to Boon’s strangulated howl, the singer questioning his punk integrity: “I’m Full Of Shit!” His sour self-doubt eventually spills over in a finale of white noise and wigging guitar. In the nick of time they suppress the release, so as not to imply resolution. Only 85 seconds long but sporting roughly a dozen transitions, ‘Self Referenced’ was the Minutemen reaching their technical peak.

‘Split Red’ from What Makes A Man Start Fires? (1983)

Listen to ‘Split Red’ here on MySpace Minutemen radio

Coltrane and spoken-word protest? Groovy. Appropriate for peak-hour Greenwich? Get the fuck out our juice bar, narc.

One of the trio’s many avant sketches, ‘Split Red’ qualifies here for one reason and one reason only; its splicing of beatnik poetry with the ungodliest guitar sound to ever depart Boon’s Fender.

If you’re going to slam imperialism over music, then fuck the bongos, cut you hair, and make it as painful as the geo-political rape of your inspiration; the sound of a great hunting knife, carving vast swathes of Central America into U.S. satellite states. Split red, all the children scream.

‘The Glory Of Man’from Double Nickels On The Dime (1984)

Listen to ‘The Glory Of Man’ here on MySpace Minutemen radio

It’s not known if, by 1984, the Minutemen were familiar obscure Factory groups but nonetheless,’The Glory Of Man’ is a dead ringer for A Certain Ratio. It’s also proof-positive that the trio did punk-funk as well as any Brit act worth mentioning.

One of the lengthiest tracks in the Minutemen canon, as a consequence ‘The Glory Of Man’ is relatively spacious, the extra minute or so allowing for a more diffuse arrangement, granting the trio an extra degree of penetrating clarity. What with the less excitable structuring and the negative space, as well as a newfound production polish and a reserved Boon, the result is a curiously cold-hearted version of the band, perfectly in service to the death-disco effect they were going for.

Illustrating the insane levels of creativity at work, on the amazingly diverse Double Nickels On The Dime, in the album’s sequencing ‘The Glory Of Man’ is bracketed on one side by polka-rock (‘Corona’) and on the other by folk (‘Take 5, D’). Each from entirely different musical universes, they are juxtaposed for no other reason than because the band believed such all-consuming genre-mastery was somehow normal. In the history of the album format, post punk, it’s a one-of-a-kind run.

‘Bob Dylan Wrote Propaganda Songs’ from What Makes A Man Start Fires? (1983)

What strikes you first about ‘Bob Dylan Wrote Propaganda Songs’ is the speed, the trio seemingly hellbent on making slow coaches out of Bad Brains. The opener to barnstormer, What Makes A Man Start Fires? (18 track in just 26 minutes), Watt is a blur, Boon a raygun and Hurley a bad influence on them both.

However, it was the title/chorus that sparked interest within the hardcore community. In some corners it was veiled hippy-baiting, in others an unforgivable championing of the old guard. Watt however had it differently. “My dad was away at sea all the time, so Dylan was like Pop to me”, he explained in We Jam Econo, “I remember thinking, if Bob Dylan wrote propaganda songs, why can’t I?” As Simon Reynolds observed, the "Minutemen saw themselves as part of a continuum with Dylan, and especially Creedance Clearwater Revival… they admired the populist class consciousness".

‘Have You Ever Seen The Rain?’ from 3-Way Tie For Last 1985

As we were saying.

Instead of the clichéd inclusion of “History Lessons Part 2”, to finish how about the trio’s equally rousing cover of CCR’s ‘Have You Ever Seen The Rain?’ The anti-Vietnam war classic, appeared on 3-Way Tie For Last which was released shortly after Boon’s fatal accident in the Arizonan desert. And yes, that is Boon’s voice you hear, the barrel-chested lug struggling passionately, contently, to reach John Fogerty’s renowned registers. As musical tearjerkers go, it’s pretty hard to top. However, it’s the harmonies that really land, Boon in (surprisingly) perfect unison with his old friend. Watt as always, in support. It’s enough to make you start a band.