All pictures courtesy the Barbican/ Main picture: Tim Whitby

Michael Clark’s visionary work as a dancer, choreographer and creator of the Michael Clark Company has a reach much further than Kintore, the tiny village in the northeast of Scotland where he spent his early childhood. Since his humble beginnings the artist has dedicated over four decades to dismantling the boundaries of dance, whipping up a frenzy, or should I say Fouetté-ing up a frenzy, in all who have seen his work.

Divine, demonic, dreamy, punk. These are just some of the words that come to mind when you watch any of Clark’s performances or choreographed pieces. His work is of a different timbre than the dancers and choreographers traditionally associated with ballet’s stiff decorum and heritage. Injecting a heady dose of sex and the carnivalesque into everything that he does, Clark has redefined the meaning of dance. Many of his works are exceptionally beautiful: they retain the intimate, intricate and technical demands of ballet. They’re as close to being works of art as dance comes. Yet this is intersected by elements of Dada, the absurd, the grotesque and bizarre.

Alexander McQueen, Leigh Bowery and The Fall are among the litany of reputable collaborators who have not only worked with but also befriended the provocative artist. From his early days as a student at the Royal Ballet School to the height of his career in the 80s and 90s, Clark has cemented his status as “British dance’s true iconoclast”, while still earning himself a CBE as well as numerous aficionados from the ballet world and beyond.

These days, Clark rarely appears on stage except for the odd brief cameo. Just as he has distanced himself from performance, he has accepted fewer and fewer press requests. As such, he is currently not giving interviews about Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer, the first full-scale retrospective of his work which opened at London’s Barbican last month. In light of this, tQ spoke to Florence Ostende, the exhibition’s curator about the artist’s collaborative spirit, his enduring relevance and his unmatched pioneering ethos. Together through ten career defining moments, we explore Clark’s oeuvre.

The Old Grey Whistle Test (1984)

Despite having performed to music by David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, Igor Stravinsky and others, it is his work with The Fall that Clark is most well known for. Clark had been dancing to The Fall long before he was introduced to Mark. E. Smith. The band’s jarring, jagged and relatively obscure sound was music to the dancer’s ears and provided ample space for Clark’s progressive, pulsating moves.

In 1984, his company began collaborating directly with The Fall, marking the beginning of a fruitful relationship that would last decades. Appearing together on The Old Grey Whistle Test in 1984, their performance of ‘Lay Of The Land’ momentarily discombobulated the (trad rock) nation as they got to see Clark prancing around in a BodyMap leotard that flaunted his bare arse cheeks.

Cosmic Dancer (1985)

Clad in a pair of slinky flared trousers, a flowing dress and a dark lipstick, Clark is as androgynous as ever. For just under three minutes he glides deftly, lilting through peaks and troughs, limbs undulating in dizzying curves. There’s something ethereal, holy even, about the way he moves. Merce Cunningham (who taught Clark at summer school) is an influence and this manifests in his swift changes of direction and emphasis on line and shape. Cosmic Dancer is an unforgettable paean to dance, an echo of the very literal lyrics: “I danced myself out of the womb. Is it strange to dance so soon? I danced myself into the tomb,” from the eponymous track by British band T-Rex which accompanies the dance.

At the Barbican, visitors are treated to a very rare group version of the dance. In the sole interview Clark gave to Ostende about the exhibition, he talks fondly about this performance, explaining how the repeated port des bras and circling arm movements “creat[e] a ring around you, something like Saturn”. For Clark, the dance is a microcosm for the societal rings in humanity. “You are the centre of your own universe then you connect with other people… there is a sort of cosmic dance,” he says.

Hail The New Puritan (1986)

“The first collaborator I wanted to have a dialogue with was Charles Atlas because he worked really closely with Clark from the very beginning. From 1984 he was designing his works and so very early on, he saw the space and we decided that he would create the major centrepiece in the entire lower gallery,” says Ostende. The resulting large-scale film immerses visitors into Clark’s early work, showcasing two earlier archive movie collages in a loop. Atlas has worked with Clark on almost every set, from designing the lighting for his show at the Whitney, to the geometric projections at the Turbine Hall.

Hail The New Puritan is a fictional “documentary” in which Atlas showcased a day-in-the-life of Clark. The friends made it before Clark became a household name, yet in the end, fiction became reality. Filmed rehearsing ballet by day and digging into the creative scene at night, the work explored the subcultures and underground artists that made up the stitches holding together London’s threadbare fabric. Though fictional, the film has strong comparisons with Clark’s much talked about dual persona as both the prodigal ballet schoolboy and the “bad boy of British dance”, the Icarus rebel. “He often talks about this Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde existence when he was at the Royal Ballet School and it was ballet by day and club by night,” Ostende confirms. The film culminates with Clark leading a mass routine on the dancefloor.

Heterospective (1989)

Michael Clark by Richard Haughton

Merely mimicking sex wasn’t the limit for Clark. In 1989, he debuted Heterospective, a work with Leigh Bowery at the Anthony D’Offay Gallery in London. This was at Clark’s peak of addiction, or as he calls them the “wilderness years”. To prepare for the piece and keep its authenticity, the dancer began using heroin. In it, he performed sex with his former lover, the American choreographer Stephen Petronio. Donning a skin coloured bodysuit decorated with syringes, Clark danced a solo to the Velvet Underground’s ‘Heroin’.

Mmm… (1991)

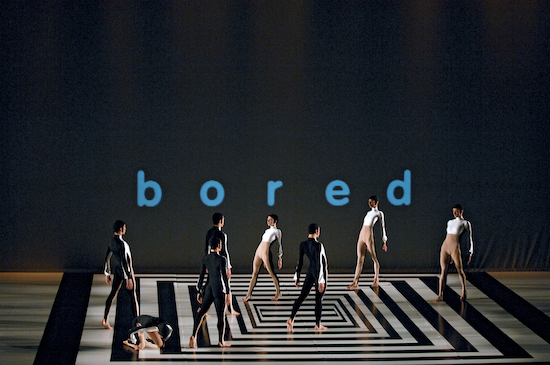

The Michael Clark Company

Michael Clark’s Modern Masterpiece first toured in Japan in 1991 before travelling to King’s Cross London the following year. It was then performed over the course of nine nights under the acronym Mmm…. In both continents, the piece didn’t fail to shock audiences. Clark famously re-enacted his own birth on stage in the second act, with his Mother Bessie, appearing alongside him as a midwife. Fresh from the womb, accompanied by Sondheim’s ‘Send In The Clowns’, he was nearly naked. Elsewhere Leigh Bowery tottered around in platformed heels, Bessie went topless and the other performers travelled across the stage in vinyl toilet costumes.

O (1994)

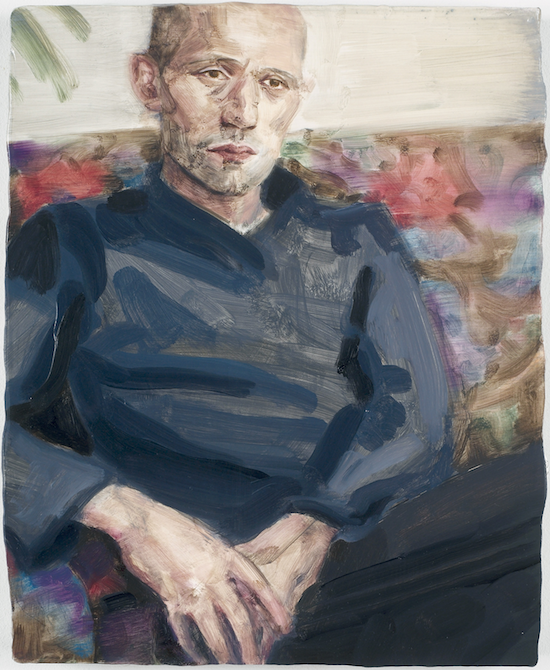

Michael Clark by Elizabeth Peyton

Inspired by Balanchine’s magnum opus Apollo, which is often referred to as the birth of modern ballet, O is one of Clark’s most critically praised pieces. It received rave reviews when it hit Brixton Academy’ stage in 1994. Like Mmm… which had come before it, O centred on the theme of rebirth. This time, Clark swaddled is white, battles with himself in a glass cage, yearning to be reborn.

Current/SEE (1998)

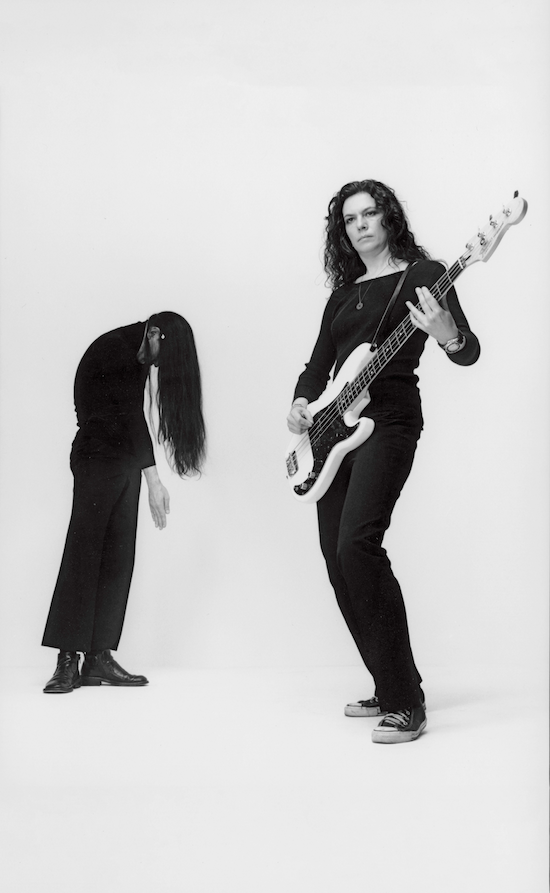

Susan Stenger

“1998 is a very important date in Clark’s life,” Ostende asserts. Indeed, it was the year that marked a noticeable shift in direction both in his personal and professional life. He had just returned from a period of convalescence in Scotland, following recovery from serious drug and alcohol abuse issues. “It’s a piece about rebirth. It’s is about how you rise again from the ground to become human again,” is how Ostende describes Current/SEE. His stint away from London’s dance scene coincided with the death of close friend and collaborator Leigh Bowery. It was a very challenging four years for the artist. However, this break provided him with the distance both physically and mentally to evaluate his career: upon return, he initially adopted a more measured process to choreography as seen in Current/SEE. Less ballet punk and more of a radical return to the Cecchetti style of his Royal Ballet School days.

“In this piece, he talks about his personal life but he puts his work at the centre through a close-up of the anatomy,” Ostende explains. “There’s this idea that his private life was often at the centre. It plays a major role in the way he is often approached for interviews,” she continues. For the exhibition, Ostende wanted to stay away from this preoccupation with Clark’s intimate life. Instead, she called on his many collaborators to paint “an intimate portrait of the artist” in an almost “curatorial methodology.”

Before and After: The Fall (2001)

Lorena Randi and Victoria Insole

Male masturbation and dance. It’s an unusual pairing, to say the least. Yet when married by creators Sarah Lucas and Clark, it’s one that works. “Sarah was influenced strongly by their shared interest in sexuality, the body and sexual arm gestures. That was the common thread between their works,” Ostende explains. In Before And After the Fall, the audience saw a giant sculpture of an arm which mimicks the motion of masturbation while on stage, created by Lucas. Meanwhile, dancers dressed as penises who were wearing little more than underwear had to weave in and out of its clutches.

Clark’s interest in exploring sex and performance stems from the fact that in ballet, sex is taboo. Throughout history, sex and ballet have stood at polar opposites: anything less PG than a Romeo and Juliet-esque romance was traditionally considered “low art”. Naturally to Clark – a man of extremes – the border between the two was fertile ground. As Ostende puts it: “He was pushing the extremes of dance by looking at how he would redefine stereotypes that were embedded in ballet history, this heteronormative tradition.”

The curator believes that this rejection of convention is what makes him resonate with audiences now. “At the time he was challenging the notions of conformity, conservative values in the context of Thatcher’s Britain,” she says. But as the youth of today continue to force open gender paradigms, his efforts in the early days as a forerunner can only be celebrated.

th (2011)

Michael Clark by Jake Walters

In 2010 Clark became the first choreographer-in-residence at Tate Modern. After his first site-specific installation in the summer, Clark returned the following year to present th. The title while standing for Turbine Hall, simultaneously toys with the interrelatedness between ‘t’ and ‘h’ and the linguistic diphthong of both letters, echoing Clark’s fascination with borderlines.

The choreographer used this opportunity to propel his work in the direction of participation. Over the course of seven weeks during that summer, a group of non-professionals and professionals rehearsed a choreographic sequence to the score of David Bowie, Pulp and Kraftwerk. Ostende sees this use of non-dancers as Clark’s way of “going against the professional artist”. Within the concrete grey confines of the Turbine Hall, Clark had 3,300 m2 of floor to play with. To get used to the space, the troupe worked on this commission during the museum’s opening hours, so that visitors passing by could watch the rehearsals.

When asked whether this interactive approach was applied to the Barbican’s exhibition, Ostende is resolute: “It is not just an alternative to a live performance. It is an exhibition in which everything from the films to the music is immersive. Organising an exhibition in COVID-19 time is very difficult. There is almost a choreography that must be thought in a different way.”

Who’s Zoo (2012)

Cosmic Dancer installation by Tim Whitby

Set to music by Jarvis Cocker (from both Relaxed Muscle and Pulp), Who’s Zoo was a 40-minute production that occupied the airy fourth floor of the Whitney Museum for its 2012 Biennial. Traditionally, the Whitney Biennial is reserved for pieces of contemporary art thus Clark’s commission re-affirms the value of his work and his well-deserved standing in the contemporary art community.

Charles Atlas’ light and film designs were projected across a huge wall of the museum, creating a backdrop for the work. Voguing and thrusting a chair between his legs in a phallic motion to live rock songs, Who’s Zoo? is less of a “dance” and more a series of moves accompanied by music.

Is it meant to be a concert featuring live dance or vice versa? Does it even matter? The production challenged viewers, forcing them to question their pre-existing notions on the limits of dance, like all great pieces of work by Michael Clark.

Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer is on at the Barbican until Sunday January 3