Apartment House plays Julius Eastman’s Femenine at this year’s Intonal Festival, on April 28

The legacy of Julius Eastman to the wider world is as yet untold. At the point of his untimely death in 1990, he left almost no tangible legacy at all. In his later years he was evicted from his home and made no attempt to recover recordings of his own music, which had been dumped on the street by his old landlord. Homeless and residing in Tompkins Square Park, Eastman died of a cardiac arrest age 49. His obituary did not appear in The Village Voice until nine months after his death.

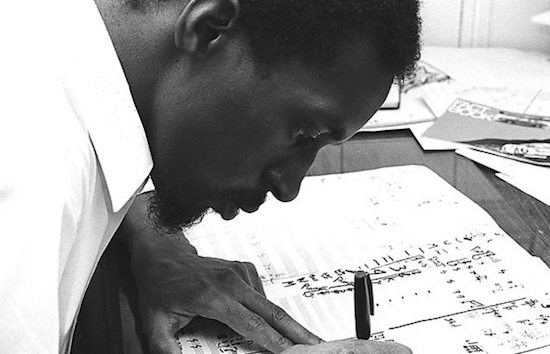

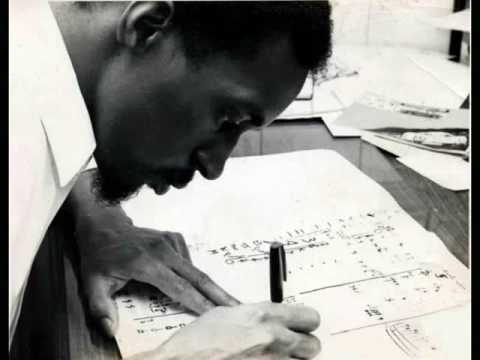

In spite of a gradually accelerating reappraisal, a full portrait of Eastman will most likely never surface. Instead we’re left to track him through anecdotes, odd photographs and his politically charged and aggressively honest personal compositions.

A recondite figure in the already weird world of 70s New York, Eastman is probably most noted for his enticing reinvention of minimalist form. But his somewhat sporadic career saw him modify the meaning of the genre, challenge the heteronormative patriarchy through means of music and voice. His varied career lead him to work and cross paths with Meredith Monk, John Cage, Arthur Russell and Mary Jane Leach.

Eastman’s small and esoteric back catalogue is constantly expanding thanks to archival releases and artist re-imaginings of his work. So, ten entry points to his back catalogue could be very different in a decades time, and hopefully will be.

Peter Maxwell Davies –8 Songs For A Mad King (1969)

Eastman is a man of multifarious ability. Not only a wonderful dancer, composer and pianist, his voice in and of itself, is nonpareil. Great in aptitude as a baritone, Eastman’s voice is also quite evasive and terrifying when he means it to be. This is evident from his performance on the fittingly evasive and terrifying 8 Songs For A Mad King by Peter Maxwell Davies, on which Eastman inadvertently steals the show. It is the musical equivalent to Ken Russell’s folk horror period piece The Devils which Maxwell Davies also wrote the score for. 8 Songs is a nightmarish piece and although Eastman’s vocal is one of the main tools for the music’s eerie feel at the time of release he wasn’t even credited on the work. This could perhaps hint at a historical act of disrespect from Maxwell Davies himself. Now, however, Eastman’s name appears rightfully on the sleeve art of a double 1987 release alongside Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot.

Julius Eastman – Stay On It (1973)

Eastman was averse to many of his avant garde classical contemporaries and that’s conspicuous in his music. There’s something discernibly exuberant about Stay On It, in the context of when and where it was released; contrasted to a classical scene that branded itself ‘highbrow’. Stay On It is flagrant but not in the way pieces like Evil N//gger, Gay Guerrilla and Crazy N//gger are – more in a sense of its musical irreverence. Stay On It embraces popular music with open arms, perhaps more than any other known Eastman ensemble piece. It gives groove to minimalism as well as using the vocal refrains of its title to create something even more compelling. With all the infectiousness of R&B and Pop and with an irresistible vocal refrain, Eastman lays the groundwork not only for a more exciting strain of post-minimalism but for also for a modern experimentalism which often prides itself on deconstructing convention.

Julius Eastman – Joy Boy (1974)

Unearthed by Frozen Reeds in 2017, this recording of Eastman’s queer-themed Joy Boy was performed by the S.E.M. ensemble, at the same concert as his well sought out Femenine. The piece consists of staccato reed and a vocal quartet that work together, in ways that are simultaneously obtuse and harmonious. The voices are strange and unwavering, further complimented by an incidental noise from shuffling audience members and chesty coughs. The naked tempestuousness of this piece can give the listener the illusion of knowing more about Eastman than is actually possible. The piece is so riddled with imperfection yet in total somehow it translates to the polar opposite. A demonstration of just how rash the human voice can be.

Julius Eastman – Femenine (1974)

This 2016 release of a 1974 Eastman performance offers a completely new perspective on his body of work. Femenine is one of a select few ways by which you can actually experience Eastman as a performer. According to many he’d always been an eccentric presence. In one instance Mary Jane Leach described him as having turned up to a choir performance dressed in leather and chains. His overt queerness, pushed Eastman away from the strictly hetero world of classical. Even the quietly queer John Cage was said to be repulsed by explicit, homoerotic reframing of his own Song Books by S.E.M. Ensemble, during which Eastman stripped male singers naked on stage.

The title of Femenine, is the first overt reference Eastman makes to gender nonconformity. While a reference to the reality of being effeminate in 70s New York is bold in itself, the piece yields something just as subversive.

In many ways it is a sister composition not only to Masculine but to Stay On It too. It shares the same buoyant vibrancy and general infectiousness. Beginning with machine controlled sleigh bells that perpetuate through the 72 minute duration, Femmine is testament to both Eastman’s sense of humour and derision of his contemporaries. This machine programmed instrument almost seems to satirise the almost industrial performance that can turn many off from the contemporary classical music of that time.

Julius Eastman – Evil N*gger (1979)

This is a part of a self-titled series, which were a collection of pieces written in the late 70s and early 80s. The pieces, and this one in particular, characterises the identity politics of his music. It’s a challenge not only to the musical politics of New York’s avant-garde, which is often documented as bigoted but also a challenge to its social politics. And Evil N*gger is one of Eastman’s loudest statements. Not only a reclamation of the slur in its title, it is formally bold and provocative with an integrally defiant and restless energy. This power is created through an evocative dark piano composition and is profoundly epic in the most acute way possible. Minimalism is often accused of being devoid of passion and emotion but this is not something that can be levelled at the work of Eastman.

Julius Eastman- Gay Guerrilla (1980)

The worlds of contemporary classical and (for the most part) the avant-garde in the 70s and 80s, weren’t the most accommodating of scenes for the person of colour or the queer alike. The miasmic entrenchment of the classical and traditional rung true then, just as many say it does it does now. As the militant queer dichotomy Gay Guerrilla is combative of this, and it is far from timid in what it’s trying to say.

Beginning in lonely stuttering notes, slowly unraveling into defiant crescendos, before the final part repurposes Martin Luther’s A Mighty Fortress Is Our God into a queer manifesto. Gay Guerrilla exposes the very best aspects of Eastman as a composer and social commentator. And while racial and sexual politics inform Eastman’s work greatly, they certainly don’t define them. He expresses feeling in its coldest and most naked form. Understanding this begins with the acknowledgment that Eastman is a black gay man. Gay Guerilla is one of the most moving pieces ever to be written for eight hands. Propulsive – it’s a bombastic tragedy, and a deeply saddening one.

Meredith Monk-Dolmen Music (1981)

Luminaries to one another, the artistic connection between Eastman and Meredith Monk was long and meaningful. While Eastman provides the foreboding organ on the opener to what many consider Monk’s opus Turtle Dreams, his monastic vocals on Dolmen Music’s final piece is their greatest collaboration. Monk’s explorations of human vocal texture enamoured Eastman more than that of any other contemporary composer. And when you look at what he tries to achieve with his own music, the connection becomes quite obvious.

Dolmen Music traverses the complexities of the masculine and the feminine through means of voice. And the climax of this record sees them combine forces harmoniously. While it would certainly be a stretch to call Eastman a gender abolitionist, with the little information we actually have about him, his work does seem intent on destroying binaries as much as possible.

Dolmen Music was later sampled by DJ Shadow on Endtroducing thus forging a tenuous bridge between Eastman and the mainstream.

Dinosaur L – 24→24 Music (1981)

Julius Eastman and Arthur Russell are not too dissimilar. It’s easy to categorise both as under-appreciated queer icons who died way too early. Both were never credited with the acclaim they deserved. Their music can be something of a hotspot for queer tourist record collectors alike. What better way to support the cause then buying into Russell who died of AIDS in 1992? That’s not to discredit straight people who love Arthur Russell – his music is about much more than being gay – but records like World Of Echo in particular will always be a sacred part of queer musical history. And revisionist history can often leave that aspect out thus erasing queer narratives.

If Arthur Russell’s lyrics encapsulate being gay in the 80s then Eastman’s instrumentals score it. Julius Eastman conducted a large amount of Russell’s orchestral recordings , but their most notable convergence comes in the world of disco arguably one of the first genre subcultures to be a somewhat LGBT safe space.

Eastman plays organ and provides baritone backing on Dinosaur L’s 24→24 Music, which is probably the biggest floor filling record for Eastman, if not Russell. At times awkwardly programmed beats, cartoonish vocals, a no wave aesthetic and lyrics like “You’re gonna be clean on your bean”, make it hard to understand. 24→24 Music is the weirdest outlier in Eastman’s Career.

Julius Eastman Memorial Dinner (2013)

One aspect of Eastman’s personality that’s often underestimated is his sense of humour. Even though he wasn’t shy of tackling grave issues this wasn’t a constant thing for him. In the excellent documentary Without A Net Renee Levine Packer describes him as “very funny but also very serious. Very serious and grave at his core even though he’d assume [resemblance] of someone who was very relaxed.” The Jace Clayton 2013 live tribute to Eastman is testament to this. As well as performing many of his pieces the show envisages a world in which Julius Eastman is a coffee table composer and household name through vignette and parody. In one instance Clayton Skype interviews Arooj Aftab for the role of Julius Eastman Impersonator.

Kukuruz Quartet – Julius Eastman Piano Interpretations (2018)

The new and justified resurgence in interest in Eastman’s music over the past few years has meant that reinterpretations of his work have become an inevitability. Kurukuz Quartet connect themselves with Eastman in 2014 where they performed his music to standing ovations in Athens. Last year the Zürich ensemble rendered four of Eastman’s finest piano pieces for CD release. Fugue no. 7, Evil N*gger, Buddha and Gay Guerrilla.

Get tickets for this year’s Intonal festival, Malmö, Sweden here