Phew by Masayuki Shioda

If punk is a state of mind, Phew – Hiromi Moritani – is as punk as they come. Plain-talking in interviews as well as in her distinctive singing style, her almost-spoken not-quite-sung delivery is a red thread that connects all her work and frequently acts as the anchor in the groups she’s played with. Her catalogue spans Osaka punk, collaborations with the kings of kosmische, sprawling experimental Japanese underground supergroups and, in the last decade, a flawless run of solo voice and electronics albums. Despite this, she remains somewhat outside of the canon of experimental electronic music, although one gets the feeling being canonised is last on her list of priorities. Her trajectory is direct and contained; moves forward like an arrow: she doesn’t look back.

One of the results of her forward motion is that she appears to remain unknown by younger audiences, demonstrated at her performance at Unsound 2022. The mid-week crowd milled about, scattered around the room chatting, as she walked on stage without fanfare. Neatly dressed with glasses on the end of her nose like a librarian, she sat herself over a table of electronics and leant into a microphone, and proceeded to unleash a heady storm of dense electronics and vocals, at a volume that matched the cavernous Teatr Łaźnia Nowa. By the end of the show, the audience was clamouring around the stage, someone stood gawping and whispered an awed, ‘Oh my God’ to themselves. "Even when I perform outside of my country, I sing and sometimes shout in Japanese," Phew says. "Sometimes [I perform] with set lyrics and [am] improvising at [other] times: ‘The weak and powerless must concentrate on the living/ If we stand still, we will be beaten/ Are you going to die like this without fighting?’ This is a part of the lyrics that I sang on my European tour last year. Though it looks like a very social message, I am not thinking of conveying anything to other people. I am always just thoroughly angry as an individual. And I think that kind of move can be shared with others. My stance is that I don’t want to ask the audience to align with me, but I just want to share it with them."

In the last few years promoters have started booking her in later slots and at club-adjacent spaces. I asked her if she has a particular fondness for either playing live or recording, as she now more often makes music from her home in Kawasaki. "I like live performances and recordings," she says. "Anything unexpected – and errors can happen at any time during live performances – I really enjoy. But I still have no idea of what entertaining people means. Since starting to make music at home in 2014, I’ve been getting invitations to DJ late-night events and parties. It feels so fresh – the atmosphere is so different to the live venues that I am used to."

Currently she’s making demos for her next album, with plans to record in the studio and invite collaborators in, too. " Currently, I’m making an album with Danielle from Hackedepicciotto, exchanging files. I’m also working with Ikue Mori and Yoshimi in the band I.P.Y., and will be doing shows this year. I also want to start collaborating with Ana da Silva again."

Phew began recording music as part of punk group Aunt Sally, which she formed after spending a summer searching out punk in the UK in the late 1970s. By the time they released their debut, she’d already moved on, but took the open book punk presented and rewrote it into a new mode of making music instead. She has spoken before of how she isn’t at her best when working with a lot of preparation, planning, or concepts, and instead works directly, which lends her work an idiosyncratic palette unburdened by passing trends in electronic music.

What she cares about most in her music is tone, as she said in a zine interview back in 1995 , and which she still holds to. "As a listener, I like music that comes into existence with just timbre and time change", she explains. "When I worked as a singer, I was more concerned about the types of microphones and the resonance of each instrument, rather than the structure of music, melody, or harmony; and that feeling has become even stronger since I started making music with a synthesizer. When making music with an analogue synthesiser, you need to set the timbre by filtering the waveform generated by the oscillator. I believe that in electronic music, this timbre is the important element that determines the music."

Her perspective was shifted drastically in 2011 after the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami which killed close to 20,000 people and triggered the Fukushima nuclear accident. Her own practice changed because she couldn’t play live or rehearse with bands while rolling blackouts were in place: "For the past few years, I’ve been making music, concentrating on the events in front of me, on my daily life." She explains: "This may or may not be directly reflected in my lyrics. It happened after the earthquake and the nuclear accident in 2011. Since then, protesting through music has become active, and I decided to participate in protesting as an individual citizen, while keeping my musical activities smaller."

Phew by Masayuki Shioda

While the obvious route through her catalogue is the autobahn of solo releases: a quick and direct journey from self-titled debut Phew in 1981 through to Vertigo KO (2020) and New Decade (2021), but to do so would neglect some important diversions. Her key collaborations include work with icons of German and Japanese music: Ryuichi Sakamoto produced her first single and played on her 1980 album; her self-titled debut was produced by Conny Plank with Jaki Liebezeit on drums; Our Likeness (reissued by Mute this year) includes Neubauten guitarist Alexander Hacke and DAF and Liaisons Dangereuses’ Chrislo Haas; Project Undark was a trio with Dieter Moebius and author and artist Erika Kobayashi, and 2018’s Island is a conversation with The Raincoats’ Ana da Silva. However, what’s often missed outside of Japan is the number of other groups and assemblages she’s played with – some of which are fairly hard to hear outside of their CD releases. In the mid 90s she formed confounding experimental group Novo Tono, then later in the decade hi-octane pop-punk group Most and a duo called Big Picture with Hiroyuki Nagashima (who mixed her solo albums). Like everyone else making experimental electronics at the time, she appeared on a project led by Bill Laswell called Blind Light, who produced a very good, one-off album reinterpreting the music of the Golden Palominos. She also did a stint in Otomo Yoshihide’s John Zorn-like New Jazz Ensemble; guested on experimental pop-rock group Hikashu’s self-titled album, and played on American musician Anton Fier’s Dreamspeed (alongside Bootsy Collins).

If Phew often seems short in interviews it’s not because she’s unfriendly or rude, but that she doesn’t much like looking backwards and doesn’t mess about with nostalgia or romance. It’s here I still find vestiges of her punk beginnings: in an artistic outlook of ‘doing’ and not overthinking, and in which she also appears to be without a clomping ego. This was at its bluntest in an exchange for Tone Glow, where she talked of having made "tons of trash", resisting any philosophising about the "whys" and "hows" of this judgement. It’s just what she’s like, she says. It’s trash, she moves on. "I don’t listen to my old works because I have so much else to listen to," she explains "And for me, nostalgia is sweet, but it can also be dangerous. It can stand in my way [and prevent me] moving forward. I always feel embarrassed talking about the past. But I do think that I am what I am now, in extension of what I have done in the past."

Aunt Sally – Aunt Sally (1979)

Phew found punk after seeing The Sex Pistols on TV, aged 16. "In December 1976 their live video was aired on TV for a brief second. It was so sensational, I really wanted to see them live. So, I called a fanzine publisher in the middle of the night, and got the information about their live [show] at ‘Islingtongrin’. It was great and etched their name into my brain. At the time I was a troubled child. I was wandering around instead of going to school and my parents – who didn’t know what to do about it – agreed to send me to a summer school in England. My classmate went to the summer school every year in Folkestone in England, and so I went there with her from July to August 1977. Every weekend, I traveled to London. I believed I would be able to see the Pistols if I went to ‘Islingtongrin’, but no one knew such a place. But I did spot Sid Vicious at the Roxy. And saw bands like The Damned, Ultravox!, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Elvis Costello, Penetration, Doctors of Madness, Adverts, Models and so on, at the Marquee, and Vortex. What I remember most is that whenever the DJ played ‘White Riot’ and ‘Boredom’, the floor got really wild. I saw The Damned in the front row of Elvis Costello’s show, really enjoying themselves. People who came to the Roxy were all kids of the same age as me, and so we enjoyed playing around together, comparing how far we could spit. When I visited London again in 2017, my hotel was near the venue in Islington, and it wasn’t until then that I realised – and was touched – that ‘Islingtongrin’ was actually a cinema, Islington Screen On The Green."

On that trip she realised punk was "not something you were supposed to watch, it was something you were supposed to do," as she later told The Wire. Back in Osaka she formed a band with guitarist Bikke (aka Yasuko Mori) and they began playing punk covers. But after being billed with a band with the same Ramones tunes in their repertoire they began writing their own material. These songs stood out amid fast and furious punk ragers, being dirgey and spare in parts, and running at a celebratory clip on tracks like ‘Subete Urimono’. The debut Aunt Sally record came out in spring 1979 (reissued in 2022 by Mesh-Key) by which time punk was dead, and Phew had moved on. However, it caught the ear of Ryuichi Sakamoto, who offered to record Phew’s first solo single ‘Shukyoku (Finale)’, which bridged Aunt Sally and Phew.

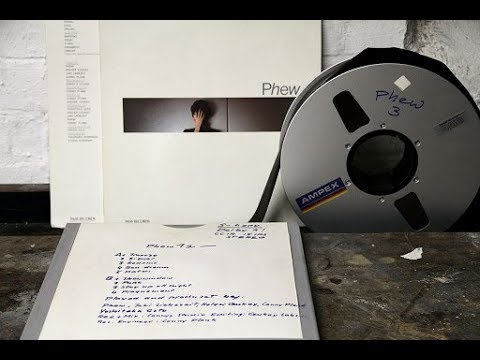

Phew – Phew (1981)

The first major junction in Phew’s sound comes between Aunt Sally and her 1981 debut album, which includes kosmische legends Conny Plank and Holger Czukay, with Jaki Liebezeit on drums. There is an immaculate architecture between her vocals and his percussion that feels like it’s being erected in real time in front of your ears: chug – snap – utterance, like musical Meccano. It had come about because the year before, the owner of her label was in London producing Ryuichi Sakamoto’s album, and visited Plank’s studios. "Holger Czukay happened to be there, and he had a copy of my single ‘Shukyoku (Finale)’," she explains. A plan to record at Conny’s was fixed there and then. She already loved Can, and said Plank was ‘godly’ to her at that point. She improvised vocals, a strategy that became a blueprint for her lyrics, which sometimes borrow common conversational phrases (a beginner in Japanese will be able to understand phrases here and there). "I had not prepared anything whatsoever, and so I wrote the lyrics on the spot, and made the tracks in the sessions. Conny Plank, Holger and Jaki all wanted to know what the lyrics meant. When I explained it to them – for example with the track called ‘Aqua’, they reacted with a very sound metaphor: ‘It must be something like [Giorgio de] Chirico’s painting’, they said. That’s how we built up the basic sound. I was so touched by the fact that they all listened sincerely to the words of a 20 year old with no experience." If you love this, head next to the gutsy, sprung songs of Phew’s other German album, Our Likeness, recorded at Conny’s a decade later, reissued last week by Mute. It features Jaki on drums again, with Neubauten’s Alexander Hacke and DAF’s Chrislo Haas.

Phew – Songs (1991)

Really this slot could have been filled by one of Phew’s jangly new wave song-based albums like View, or Himitsu No Knife, or Shi-a-wa-se No Su-mi-ka, an EP with regular collaborator Seiichi Yamamoto, which isn’t unlike some of Jim O’Rourke’s song-based albums. But I have a fondness for the lesser known Songs EP, because it is easy and free; its opener is pure LA sunset driving, with the same electronic filters as YMO’s ‘Wild Ambitions’. Its four tracks also include a punk track by Bikke, Aunt Sally’s guitarist, and contributions from Friction’s new wave guitarist Tsunematsu Masatoshi. It is imbued with a fringe-pop sensibility, and says she recalls Conny Plank saying that he liked music that ‘sounds pop at first, but is actually weird’. "It’s not so long ago that I realised that the music that’s been played for decades is really well made, and has complicated structures as well as quite a lot of weird parts within them," she says. "I realised the greatness of ABBA for the first time, a few years ago." If this Phew appeals, make yourself a playlist of the Songs EP, View and Himitsu No Knife, and put it on repeat.

Novo Tono – Panorama Paradise (1996)

Like other groups experimenting with electronic instruments, early sampling technologies and an extravagant drum setup, Novo Tono has an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink feel. It was a supergroup of sorts, that included Phew, Osaka underground lynchpin Seiichi Yamamoto (a regular collaborator who runs the venue Bears, the label Ummo Ummo and was in Boredoms), Otomo Yoshihide, drummer Masahiro Uemura, Naoko Eto and Yusuke Nishimura, a Tokyo punk from the second iteration of (The) Stalin. "I think Novo Tono played two or three shows a year," writes Phew. "The members got busy with their personal lives and the band naturally faded away."

It is a confounding, unclassifiable album that opens with the light strumming of acoustic strings, Phew humming, and asking (in Japanese), ‘Are you OK?’ After this gentle intro, it warps into a madly flexing & belching speed-skronk that occupies a space somewhere in the chasm between Ruins and Mr Bungle – being less jazzy and slower than the former and less stoopid than the latter. The better tracks leapfrog over genre and mood, and, in ‘Koko Kara no Shuppatsu’, settle into a groove; ‘Hakujitsumu’ evokes Stalker-like edgelands; ‘Umi e Iko’ is bordeline anthemic. Phew is a constant in this baffling juggernaut of experimentalism, her narrations anchoring the whole operation.

Most – Most (2001)

The fast and blousy pop-punk of Most is what Aunt Sally would be like if they’d carried on, got jolly, and beefed up their sound, or rather, if they were a totally different type of punk band. There’s an infectious energy to this group, with a well-fattened backline of drums and bass that fills the sound field, keeping pace with Phew, who vocally sprints through some big hitters. Added fuel comes from an occasional oi! chorus and a lead guitar that sounds like a spiked mohawk – a swaggering, sharp, statement of intent. "When singing in a band that plays loud, you simply have to sing out louder to be heard. It’s a completely different way of singing from when I’m working solo," she says. "As for the lyrics, it was the same as with my solo work; I’m often singing about emptiness and de-personalisation, in a non-didactic way."

Also in Most were Seiichi Yamamoto (again), with Hisato Yamamoto, Masayuki Chatani, and Yusuke Nishimura. Pretty much only available on CD at this point, their debut Most is marginally more joyfully furious than their second album Most Most, but it’s only by degrees. It’s possibly the most big-fun album in Phew’s catalogue. "Around 1999 when I formed Most, ‘punk’ had become well established as show business in Japan. Albums became million-sellers, events were held in stadiums," she explains. "Although I thought it was wonderful that they succeeded on such a big scale independently, I felt really uncomfortable hearing the bands singing melodious English lyrics with big smiles on their faces. That’s one of the reasons we formed Most. We did about three events in venues with capacity of less than 200 people. We weren’t thinking of appealing to the mainstream, but as we did our shows, more and more people came to see us."

Phew – Light Sleep (2012)

2012’s Light Sleep is crucial, as Phew’s first solo electronic album. This change was ultimately caused by the upheavals and implications she felt following the 2011 earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear disaster. She has spoken about feeling that her reasons for making music had become questionable, and that her day-to-day situation changed when she couldn’t play live due to rolling blackouts. In an interview in 2020 with her friend, the musician Danielle De Picciotto for Kaput magazine, she explains how she yearned for synths and electronics in the late 70s when they were unaffordable. In the 80s she toured with a sequencer that would lose data mid-performance, and eventually lost interest in the increasingly technotopian discourse, until 2011. Light Sleep has crunchy Craig Leon-like percussions, sometimes agitated and sometimes spaced like stepping stones too far apart to jump between. In her largely Japanese-language vocals there remains a previously unheard emotional intensity even without translation.

Phew – Voice Hardcore (2017)

2017’s Voice Hardcore is made purely with the voice. In its wake followed the (also essential) Light Sleep and Island, one of her most important collaborations in recent years, made with Ana da Silva from The Raincoats. It’s dreamy and strange, with a title that hints at moods for the largely abstract pieces of layered and looped breath, non-verbal utterances and short melodic phrases, it contains. It was recorded, as the credits state, "In Phew’s Room in 2017". She lives in Kawasaki, a city outside Tokyo, and this influences the content of her lyrics, in which she says she sings about things that come to mind, and because she lives in a boring place. "When using my voice, I put emphasis on physical sensations," she says. "It feels good when I let my voice out when I’m breathing deeply. I don’t know much about perfection or entertainment, but I trust my sense of pleasure for judging, as it is something that comes from my physical sensations."

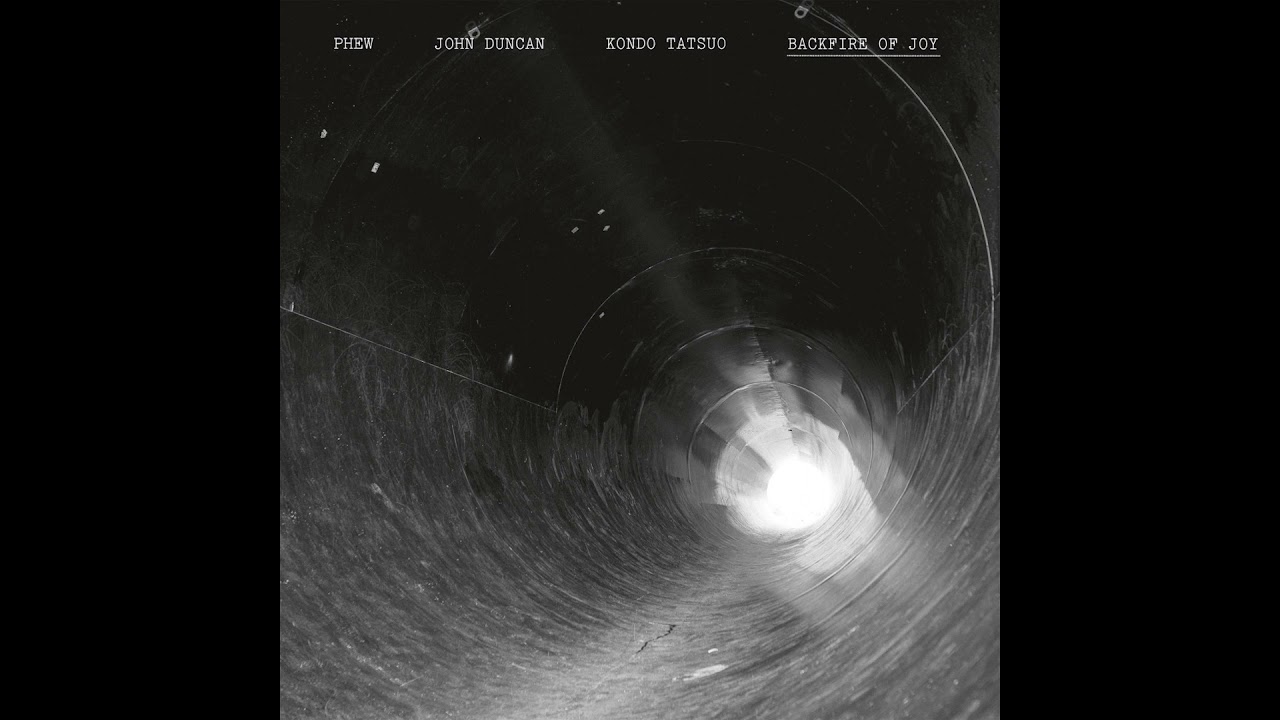

Phew/John Duncan/Tatsuo Kondo – Backfire Of Joy (2021)

Backfire Of Joy is an absolute standout collaboration in Phew’s catalogue, despite only being released for the first time in 2021. At this 1982 meeting point between the Japanese experimental scene and the Los Angeles Free Music Society [LAFMS], Phew is at her most acutely plain-speaking, her no-frills delivery in absolute accord with John Duncan’s shortwave radio set-up and Kondo’s synths, tape and other treatments. The list of electrical household items that comprises most of ‘Backfire’, backed by various mechanical stabs of sound, is a tractor beam of radically and idiosyncratically reimagined possibilities for what we might think of as industrial music.

Phew – Vertigo KO (2020)

Vertigo KO might be thought of as the initiator of Phew’s stellar run of releases, where something in her sound synced with a cultural consciousness and brought attention back to her work, particularly through the networks of UK label Disciples. At this point, the combination of heavy zoned-out textures and her half-spoken vocals have fully settled into an inimitable style. The tracks on here started their life as a collection of six CDRs that she sold at live shows between 2017 and 2019. When someone from the label first approached her about a release, she apparently said something along the lines of ‘I hope you’re not one of those post punk boys who just wants to reissue my old music.’ Think of this one as being in a pair with New Decade, which is also essential.

106 – DTP01 (2022)

This final entry looks beyond the present. DTP stands for ‘desktop punk’ and is Phew’s duo with her partner, the composer Hiroyuki Nagashima aka Dowser. Currently with two tapes albums – both released with little fanfare last year – under their belt, 106 appears to be the beginning of an ongoing project which has an immediate sense of experimentation. It feels like a return to the freedoms and play of some of her collaborations of the late 90s, but with the added control and style that she’s cemented since then.

Phew plays Intonal festival this April in Malmö, Sweden. The album Our Likeness is out now on Mute