Organic Music Theatre in Warsaw, ca 1973, courtesy of the Cherry Archive/ the estate of Moki Cherry

Ornette Coleman said Don Cherry had an elephant memory. Those who played with him said he could hear a melody just once and be able to reproduce it perfectly. This ability – combined with listening to shortwave radio from all around the world – provided the raw material for his compositions, bringing the whole world into his music from early on in his career. He began as one of the best post-bop trumpeters of the early 60s; in his primer on him in The Wire, jazz writer Brian Morton names Cherry as one of the three most important post-war trumpeters, along with Chet Baker and Miles Davis. By the 1970s, he had become the co-founder of a communal form of music-making, teaching, and living, with his partner Moki Cherry, where, as her motto went "the stage is home and home is a stage".

Don Cherry was born on 18 November 1936, to African and Choctaw parents in Oklahoma. The family moved to California when he was four, and he started playing a trumpet his mother gave to him aged 14, a gift from which the rest of his life flowed. Cherry’s primary instrument for most of his life was a humble pocket cornet – the one he played most often was a cheap model made in Pakistan. He played many instruments, and sang, having studied for a short period with Pandit Pran Nath, and later took up the donso ngoni, a hunter’s harp from Mali.

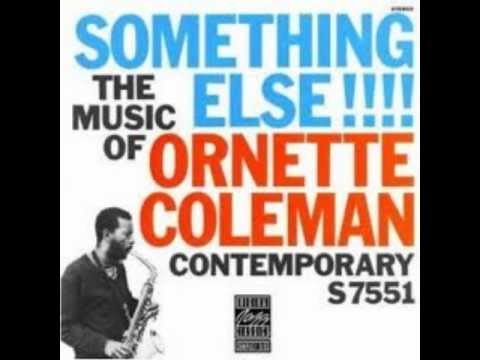

Don Cherry’s first appearances on record were with the Ornette Coleman Quartet. In her definitive book on this period of jazz, As Serious As Your Life, Val Wilmer describes the "quick-thinking" Don Cherry as Coleman’s "musical and personal alter ego". He and Coleman met when they were young, and wound up living together on the west side of LA. After getting signed, they moved to New York, where the Coleman Quartet had a residency at the Five Spot club, which was hailed by some as the New Thing and utterly derided by others (Miles Davis did not rate Cherry’s trumpet playing). Cherry and Coleman’s collaboration on record ran from Something Else!!! to 1971’s Science Fiction, but they played together on various occasions after this.

He played in Paul Bley’s quintet in the late 50s; in The New York Contemporary Five with Archie Shepp, John Tchicai, Don Moore and J.C. Moses; with an Albert Ayler quartet that also included Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray, and in the shifting melee of the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra and on Carla Bley and Paul Haines’s Escalator Over The Hill, as well as with John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Pharoah Sanders. Cherry had his own Quintet, but it didn’t stick like the Coleman group. Cherry called his pieces "collage compositions", but became disillusioned with the structures and demands of the jazz club and abandoned it for a radically different form of music-making.

Don Cherry met Moki Karlsson in 1963, on a night when she recalled the venue being on fire: “smoke was seeping through the floor, but no one moved”. He was in Stockholm playing with the Sonny Rollins Quartet, and Moki had seen them play before heading onwards to the smaller jazz club The Golden Circle, along with many others, including the Quartet. Two years later they had committed to forming a life together, and Moki began occasionally contributing costumes for the band. Their collaboration grew into a utopian vision for living and creating art.

In 1967, Organic Music Theatre (originally called Movement Incorporated) staged their first concert. By the end of 1970 they had bought an old schoolhouse in Tågarp in southern Sweden and moved in. The schoolhouse was a utopian form of collective and communal living and music-making, and Organic Music Theatre a manifestation of Cherry’s regular insistence that the music did not belong to him. He became part of a project that was a confluence of music, art, and languages from across the globe, which was more free-folk than jazz, and that valued teaching and the creative instincts of children within its sphere. It was a philosophy that, in the way it operated at least, was at odds with some of his peers, who were searching for a different truth through sound. It was also an escape into a healthier lifestyle and away from the city, an enabler of Cherry’s addictions.

However, by the end of the 70s the vision had faded. Cherry went on to form the trio Codona and the quartet Old & New Dreams, and later, the far clunkier fusion group Multi Kulti.

Bobo Stenson (seated on far left), Jan Robertson (cello), Christer Bothén (sax), Eagle-Eye Cherry (seated in foreground); bottom row: Don Cherry (horn), Palle Danielsson (bass), Moki Cherry (tanpura), courtesy of the Cherry Archive/ the estate of Moki Cherry

There is something deeply sympathetic in all of Cherry’s music, in the shaping of the sound and the way influences are melded without visible joins. Writing on him often mentions how much he loved to spin the dial on shortwave radio, and is key to understanding the fusion of sounds, melodies, song forms and tunings that appear on his records – his was a pan-global folk music that rejected territorial boundaries. This notion of music as a universal language was present in his groups on a fundamental level – one group did not have a shared language between them, forcing communication to happen in other ways.

There are many unexpected appearances and diversions in Cherry’s output, which speak to an open mindedness, whether or not a collaboration delivered results, and many people passed through Don and Moki’s sphere. The Taj Mahal Travellers went to their "living exhibition" Utopias & Visions in Stockholm, where people gathered daily under a geodesic dome. Don also collaborated with Synclavier developer Jon Appleton on a human-computer collaboration while teaching at Dartmouth; appeared on harpsichord and as part of the chorus on Allen Ginsberg’s recordings of Songs Of Innocence And Experience; was recruited by Jodorowsky for the soundtrack to Holy Mountain, and met James Baldwin in Istanbul, which resulted in Cherry making music for a theatre production of John Herbert’s Fortune And Men’s Eyes.

How Cherry’s catalogue is presented often leans into either his foundational jazz playing, or the middle and latter period of communal free-folk. These two zones are sartorial too: compare the image on the Ornette Coleman Quartet’s This Is Our Music – suited and booted and looking sharp – to the Cherry of Organic Music Theatre, in rainbow knits, kaftans and colossal scarves. This article leans towards the latter as the compositional paradigm he strove towards, but jazz writer Brian Morton’s primer for The Wire in 2013 provides an essential blow-by-blow account of Cherry’s roles in many of his earlier groups, as well as his playing with Archie Shepp, John Coltrane and others.

Don Cherry died of liver cancer in Malaga, Spain age 58, following a period of declining health. His playing, whether with Coleman or the Organic Music Theatre, was a serenade to energy, and later, to nature. As Moki writes, "the pocket trumpet was a minute instrument but Don made it big. He could make its sound cut the air and take you for a journey. The pocket trumpet was his soul instrument". Whereas other spiritual jazz players such as Alice Coltrane were looking at life beyond this plane, Don Cherry strove to create a utopia in an earthly realm.

1. Ornette Coleman – Something Else!!! (1958)

Don Cherry played on the first seven Ornette Coleman albums – they met young through Ornette’s first wife Jaynie who went to school with Cherry. Cherry said that the way Coleman wrote made “the music flow like water”. All of the early Coleman albums are essential, but Something Else!!! with its well-earned triple whammy of exclamation marks is a bold and swinging entrance for Coleman and his band, on which Cherry’s trumpet is fierce and sharp, cutting through the air like shears through satin. Brian Morton and Richard Cook’s Penguin Jazz Guide states that: "It’s almost impossible to reconstruct the impact – positive and negative – Ornette’s Atlantic albums had when they first appeared. They are classic performances and scarcely bettered since."

2. The New York Contemporary Five – Volume 1 (1964)

Only existing for one year, and doing most of their playing in Europe, The New York Contemporary Five nonetheless made a mark – their sound had sass and swing, Cherry’s horn often sharp and clear like glass against softer reeds, and a number of albums came from their recordings. They formed because soon after arriving in the Big Apple in 1963, the Danish saxophonist John Tchicai was offered a gig back in Copenhagen at the Café Montmartre if he could get a band together, and Shepp was butting heads with Bill Dixon in another group. They split, and The New York Contemporary Five was formed, with Tchicai, Archie Shepp, and Don Cherry on horns, with J.C. Moses on drums and Don Moore on bass. They played Thelonious Monk and Coleman compositions, with a piece by George Russell as their theme. There is a full playlist of Volume 1 here.

3. Don Cherry – Complete Communion (1966)

The first of three records made for Blue Note in the mid 1960s (followed by the essential Symphony for Improvisors), Complete Communion was Cherry’s debut as bandleader, and significant because of its structural form of improvising and music-making whereby each member of the band is given space to solo (not standard at that time). It includes the brilliant bassist Henry Grimes and drummer Ed Blackwell, with Gato Barbieri on tenor saxophone. Improvisation often worked with a composition at its foundation, but Cherry began working instead with themes. To my ears, this is what lends Cherry’s work a mnemonic or earwormy quality, whereby recurring motifs become anchors in the music – the title track is a perfect example.

4. Don Cherry – Eternal Rhythm (1969)

Widely hailed as a masterpiece, Eternal Rhythm was recorded in 1968 and released a year later. It is the connecting piece between the pace, tension and excitement of Cherry’s free jazz playing in Ornette Coleman’s groups, and the relaxed invitation to international and folk forms of rhythm that came later. I hear this album as movement between moments, and am lifted from my seat with sheer joy, any time I hear the marching theme land 12 minutes into Part One, after the frenetic generations of the rhythm section and Sonny Sharrock’s guitar are batted away by Cherry’s trumpet herald, and the band falls into step for a few brief and triumphant turns around the parade ground.

5. Don Cherry / Krzysztof Penderecki – Actions (1971)

I would like to have been in on the meetings when the pitch was made at Donaueschingen festival to put the composer – whose work ended up on the soundtracks to The Shining and The Exorcist – together with not just Don Cherry, but a one-time-only all-star avant-garde jazz group called The New Eternal Rhythm Orchestra, which included Peter Brötzmann, Han Bennink, Albert Mangelsdorff, Gunter Hampel and others in its number. Incredibly intense and frenetic, two of these pieces were composed by Cherry and one by Penderecki – the authorship is audible.

6. Don Cherry – Organic Music Society (1972)

This entry is actually both for the 1972 album and the recent journal that both take their names from these recordings, with the Blank Forms 06 – Organic Music Societies publication being released earlier this year. The Organic Music Society period is the beating heart of Don Cherry’s oeuvre, in that the music recorded does not belong to him, but was communally created – the ecstatic, multisensory, and communal manifestation of his mantra ‘this is not my music’. The album Organic Music Society is just one artefact from this crucial period, more fully documented in the essential Blank Forms journal Organic Music Societies, which gathers together personal essays from a number of friends and collaborators, with interview transcriptions, Moki’s diary entries, images of her early paintings and photographs of the places they created. For full immersion, listen while reading. To hear its opening chants is to invite a feeling of happiness and ease.

7. Don Cherry – Brown Rice/Don Cherry (1975)

Recorded while still in the communal Organic Music Society period, this album is called by two names – Brown Rice or self-titled. It is perhaps the best entry point to Cherry’s work, and contains some of his most memorable tracks in melodies that follow you long after the album has finished, from the riff on ‘Malkauns’ (named after one of the oldest Indian ragas) to the joyful whisper-along invited by the hushed health food words that form the lyrics to the title track. All together now… “brown rice… miso”.

8. Don Cherry/Terry Riley – Live In Koln (1975)

Never officially released, this absolutely killer bootleg periodically pops up in various short run anonymously-released editions. Cherry’s trumpet playing here sounds like it is serenading the moon, or perhaps the whole swirling cosmos of life. His trumpet is a heron and Riley plays a silver-lit pond. However, while I adore this recording, unfortunately I hear the generic sports chat “Who are ya? Who are ya?” in the organ motif about Riley plays roughly three minutes into ‘Descending Moonshine Dervishes’. Sorry.

9. It Is Not My Music (1978)

This TV documentary was made for Swedish TV in 1978 and follows the Cherry family between Sweden and the streets of New York. Don can be seen setting up jams in classrooms and on the street with the donso ngoni, at one point cajoling a car of reluctant strangers waiting in traffic into joining him. When Don is interviewed, he is deeply sensitive about sound and environment, and the footage from the places they lived show how much Moki’s tapestries created a place for them all to be, wherever they were in the world. Essential.

10. Codona – Live In New York (1984)

Cherry made some of the finest music of his later career with Codona and the quartet Old & New Dreams. Formed in 1978, Codona was a trio of Cherry with American sitar player Collin Walcott and Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos. They released albums on ECM in 1979, 1981 and 1983 (later released as a trilogy) with compositions by Ornette Coleman pieces. This stellar live recording was made in New York in 1984, shortly before Walcott died in a traffic accident.

The new journal Organic Music Societies and Don Cherry’s The Summer House Sessions are both out now on Blank Forms