Free improvisation is to music what poetry is to writing – not only is there a lot that is prosaic or downright terrible due to the inherent risks of the form, but there’s also a lot of people who think they don’t ‘get it’. Derek Bailey is one antidote for anyone who thinks they’ll never understand improvised music. His guitar playing is that which requires a surrendering to your own ears. The best listening advice is not to overthink it. It is what it is, and that’s exactly what he intended it to be. “What I do is not precious,” he told his biographer Ben Watson, “there are times when I’ll play with more or less any fucking thing.”

Bailey wrote that improvisation is the most practised but least recognised or understood forms of music making, and described what drove him as an “impatience with the gruesomely predictable”. His legacy can be traced in many tangled paths and his influence has been enormous – this is as good a juncture as any to note that Stewart Lee chose Bailey as his Celebrity Mastermind topic and won. However, his continuing relevance has as much to do with his commitment to the operations of non-mainstream music as it has to do with his playing, and his influence still towers above the experimental music scene in the UK. To really appreciate the radical flavour of the free improvisation project in its early days in the 1960s, consider Gavin Bryar’s assertion to Watson: "I heard Derek Bailey do feedback before Hendrix."

Derek Bailey was born in 1930 in Sheffield. By the 1960s he earned his keep as part of theatre bands (he played in the pit for Morecambe and Wise, among many others) and night clubs of the time – playing jazz at tea dances. In the early 60s he formed the Joseph Holbrooke Trio with Tony Oxley and Gavin Bryars, when Bryars was a 19-year-old philosophy student playing bass, and Oxley and Bailey were playing in a cabaret band in Chesterfield. They disbanded in 1966, but not before laying the groundwork for free improvisation in the UK. When Bailey moved to London, he became involved with John Stevens’ Spontaneous Music Ensemble, and started the Incus record label with Tony Oxley and later with Evan Parker, which is often said to be the first ever artist-owned record label.

Over the decades, Bailey developed close musical relationships with Oxley, Parker and Stevens, and many of the foremost members of the British free jazz and improvising scenes. He also forged long-standing relationships with a number of European players with whom he played semi-regularly, such as Han Bennink, and in the late 70s began playing in Japan with players such as Toshinori Kondo, as well as developing fruitful relationships with American improvisers and composers like Anthony Braxton, George Lewis and John Zorn, among others.

The sheer volume of people he played with was partly down to his openness to playing with anyone, but also because he believed free improvisation groups had a shelf life of just a few years, after which a vocabulary was established and the exercise became stale and predictable. To counter this ever-looming stagnation, he set up the collective called Company, who held "weeks" where musicians from free improvisation, jazz and the avant-garde etc. would gather for seven days of mostly one-off performances. After the inaugural week at the ICA in London in 1977, they ran almost annually until 1994. Those that passed through included David Toop, Julie Tippetts, George Lewis, Akio Suzuki, Wadada Leo Smith, Ursula Oppens and many, many more. However, as free improvisation became an established scene, Bailey was dismayed by the commercialisation and codification of it as a genre, and by the end of his life believed that its best years were over.

Bailey’s output didn’t have an arc in any traditionally recognisable sense, partly because he was driven by improvisation as an experience of the moment, which is a difficult fit with record releases whichever way you cut it. As Ben Watson writes in the new foreword to his biography of Bailey: “Derek Bailey’s fame as ‘avant icon’ something that has increased exponentially since his death, didn’t serve his real intent, which was the music”. Watson’s is the essential (and only) biography of Bailey, but it’s also a biography for free improvisation, a form centred on a commitment to non-idiomatic music, on an escape from genre, and which Bailey described as being in the category of composition, rather than a genre like jazz or punk.

There is the preconception that music like Derek Bailey’s – which strives to escape genre and predictability – is difficult, but this perception occludes the fact that in Bailey there is much in the way of simple pleasures: the attack, sustain, decay of a guitar string; the play between memory and melody. As a listener, it is not for understanding, for while there was much training and practice that formed the basis of his playing, you don’t need to understand the mechanics or any music theory to enjoy it.

He is reported to have been variously curmudgeonly and provocative, and an articulate raconteur ready to bust open preconceived ideas. Quietus columnist Peter Margasak, in a feature for the journal Sound American, talks about Bailey as using improvisation "as a life force", whether or not he recognised it as such. He was also uninterested in the fame or status of those he played with – in the final years of his playing he had connected with a couple from Manchester, Marie-Angelique Bueler who improvised with bricks, and her partner Stu Calton who often used dictaphones, after they sent him a recording they’d made together in a disabled toilet in Liverpool Airport at 4am.

Within his whopping discography there are often absurd titles, from ‘Umberto Who?’ to ‘The Man From S.L.A.P.P.Y’, and Bailey’s verbal deliveries to the audience on solo albums like Aida and Lace are their own form of deadpan stand-up comedy (see especially the routine about the radio show Jazz In Britain in the last section of Aida). However, as with any effective uses of humour, his comic timing doesn’t detract from the dead seriousness of Bailey’s free improvisation project and philosophy.

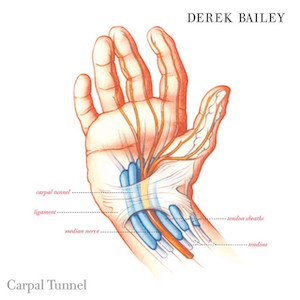

Bailey died on Christmas Day 2005 as a result of motor neurone disease that began as a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome, which he initially thought was caused by an injury sustained pulling luggage from an airport carousel. A courtyard round the back of the Vortex jazz club in Dalston is now named after him – Bailey Place. In a tribute in the Guardian the week after he died, the paper’s jazz critic John Fordham wrote that Bailey was "a guru without self-importance, a teacher without a rulebook, a guitar-hero without hot licks and a one-man counterculture without ever believing he knew all the answers – or maybe any at all".

What’s notable about his discography is not just its size but also the lack of an obvious route through it, and there are many fruitful tangents to be followed chasing archived live footage and other recorded material. As someone a few years too young to have ever seen Bailey play (give or take three years in Sheffield where I didn’t yet know free improvisation even existed) I am trapped in the problem that prompted David Grubbs’ Records Ruin The Landscape – that most of this music existed best in the moment of its creation. Navigating by the recordings alone therefore, gives a distorted outline, but it is the only one that’s left, and these selections are informed by my personal favourites (which may not be yours) along with some important historical way markers.

1. Joseph Holbrooke Trio – Miles Mode (1965)

Bailey met drummer Tony Oxley when they were playing in a cabaret band in Chesterfield, and Bryars was a 19-year-old student and bass player. They were named after Holbrooke, a composer known as the ‘cockney Wagner’, although the in-joke was that they never played any of his music. The Joseph Holbrooke Trio represent the beginnings of free improvisation in the UK, where foundations were laid at regular shows in small Sheffield venues, although little was captured on tape so most of what was played is lost. In Bailey’s book Improvisation, Bryars explains how the trio led to him abandoning improvisation for composition and Bailey counters by articulating how the trio reinforced his faith in the practice. It is one of the most revealing and fascinating parts of the book – a philosophical conversation between opposing sides, where it’s possible to agree wholeheartedly with both.

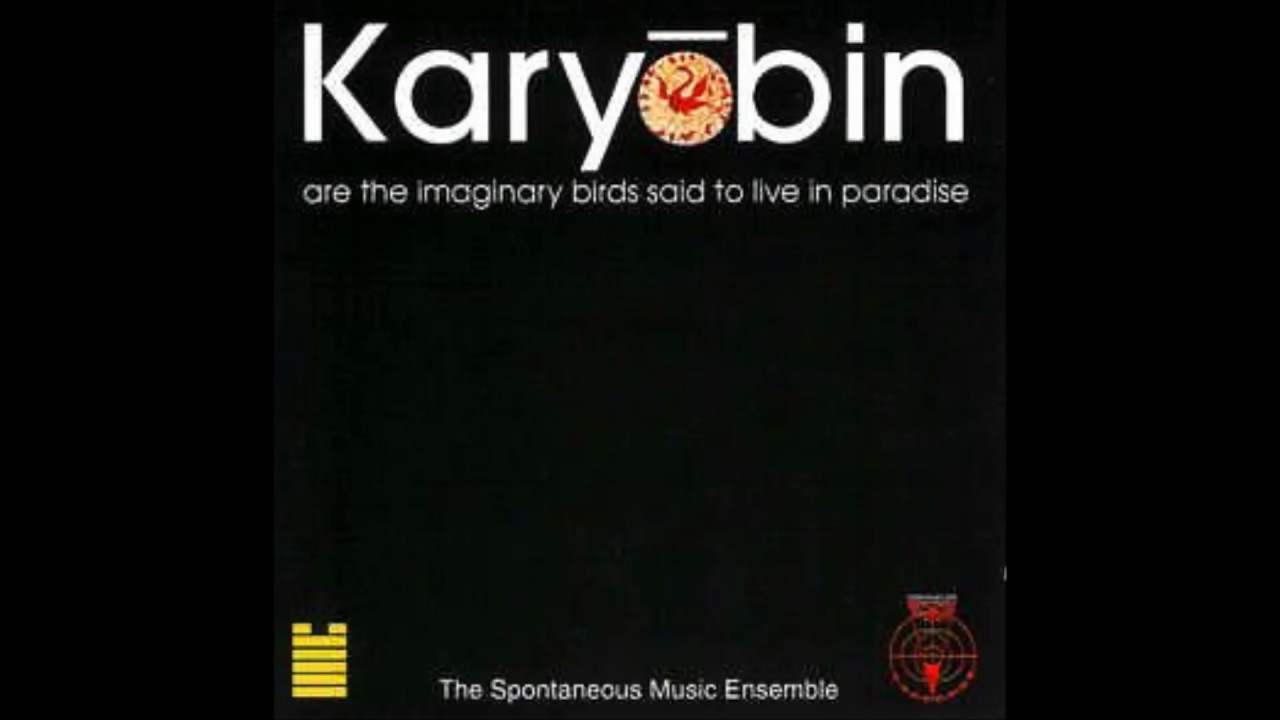

2. Spontaneous Music Ensemble – Karyobin (1968)

This was Bailey’s first appearance on record (The Joseph Holbrooke trio material wasn’t made available until much later) although he had been working as a jobbing musician for decades already. The Spontaneous Music Ensemble consisted of Evan Parker on saxophone, Kenny Wheeler on trumpet and flugelhorn, Dave Holland on bass and John Stevens on drums, with Bailey on electric guitar. While there is a strong jazz inflection to the improvisations here, Bailey’s guitar is coming from a slightly different place, which becomes particularly stark in the moments it rubs up against Wheeler’s trumpet. This is an album on which free improvisation is emerging as a form, and where Bailey’s resistance to it being a sub-category of jazz is audible. The early-ish ensemble piece to follow this up with is Iskra 1903 – a different mood entirely.

3. Derek Bailey – ‘Where Is The Police’ from Solo Guitar Volume 1 (1971)

Those expecting Bailey’s free improvisation to be unlistenable or directionless would do best to start with his solo recordings, especially the tracks with titles on Solo Guitar Volume 1, such as my personal favourite, ‘Where Is The Police’. This track has a particularly odd charm, a simplicity and a tunefulness. It is even – however unlikely this may sound – Deerhoof-ish in its plink-plonking. It is a track on which the sounds of the world outside are drawn into the playing, and proof that free improvisation isn’t always impossibly abstracted. From here, search out Ballads, especially if you love Bill Orcutt but have never got started with Bailey. Derek Bailey thought his solo playing was a test of whether his guitar-playing vocabulary was complete, and more generally speaking I find Bailey playing solo to work best on record. For me, group sessions often don’t fully capture electrifying free improvisation performances, as there are often important visual or tactile elements in non-traditional approaches to instruments – the frisson of knowing exactly how an instrument was being played ‘improperly’ can be lost when image is detached from sound. Notably, Bailey did not play his guitar ‘improperly’ – it was never hit, laid on the floor, or on a tabletop, and so there is less mystery about the mode of a sound’s source.

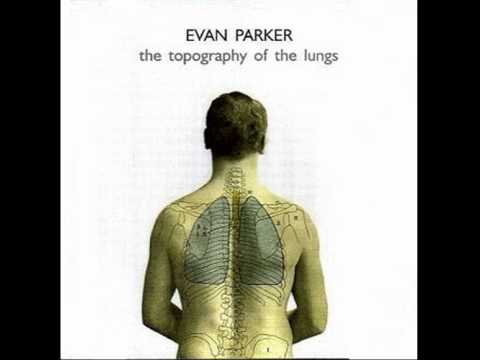

4. Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, Han Bennink – Topography Of The Lungs (1970)

Incus was said to be the first artist-owned record label, started in 1970 by Bailey and Tony Oxley with Evan Parker, and funded by a chap who wanted nothing to do with the running of it. Topography Of The Lungs was the first release, with Parker and Bailey and Bennink on drums. Its status and mythology grew after Parker’s acrimonious split from the label meant it could not be reissued, and so very few people heard it until after Bailey’s death when Parker put it out on CD. It was later brought out of the shadows on Cafe Oto’s OtoRoku label. Its tight and ferocious energies are said to have a prosaic source: Bailey’s annoyance that Bennink and Parker turned up late having got stuck in traffic.

5. Company – Company 4 (Derek Bailey and Steve Lacy) (1976)

The Company weeks were almost-annual gatherings of musicians playing in ad hoc groupings that ran from the late 70s into the 1990s. Company was a play on words – Bailey said its name was taken from a theatrical repertory company, but it was prompted by the desire to play in the company of other musicians. In the 90s the programme stated that it was not a festival, as "festivals are fashion parades" but "a building site, we get together and build something that wasn’t there before". It is hard to pick one Company record to illustrate these sessions, particularly because a slew more recordings from these events have been issued on Honest Jon’s in the last few years. There are also a handful of early pre-Company week recordings made under the Company name, and of these Company 3 with Han Bennink and Company 4 with Steve Lacy are standouts. The conversation on Company 4 has sequences that sounds like an awkward waltz with stuttering tensions, although by the second side there’s an unkempt and unsettled groove to the exchange. The version on YouTube is a terrible, terrible rip.

6. Derek Bailey/George Lewis/John Zorn – Yankees (1982)

Yankees, with composer and trombonist George Lewis and composer and saxophonist John Zorn, is an unexpectedly restrained affair, despite the bubble-blowing, elephantine honks and birdy squawks. The playing is light-hearted and fun, with a tumbling, breathing, animal spirit, albeit a fairly domesticated one (perhaps a result of this album being recorded in a studio). Released on Celluloid, it put Bailey as a brief label mate with post punk and industrial groups, and the cover and title was spawned by Zorn’s use of sports rules as compositional strategies at the time (which later developed into compositional games such as COBRA) and was documented in the TV series On The Edge (see below).

7. Kaoru Abe/Motoharu Yoshizawa/Toshinori Kondo/Derek Bailey – Aida’s Call (1978/1999)

Aida’s Call is a deeply pleasurable listen, was described variously as an "unfolding", and as having a "narrative" – it is powerful and controlled, with a graceful no-fear intensity about it, as more trad jazz anchors surface and are swept away. The Aida in this album’s title refers to Aquirax Aida, a Japanese jazz critic and promoter, who imported Incus records into Japan and convinced Bailey to tour Japan. This album, with saxophonist Kaoru Abe, trumpeter Toshinori Kondo and bassist Motoharu Yoshizawa, was recorded on Bailey’s first tour in 1978 shortly before Abe’s death from an overdose at the age of 29. Over six weeks Bailey played almost every night to audiences of up to 700 people, and reportedly brought home enough money to buy a car.

8. Derek Bailey – On The Edge (1992) / Improvisation (1980/1992)

Once upon a time Channel 4 signed off on a 200-minute, four-part documentary about improvisation in music. Based on Bailey’s essential 140-page book Improvisation, this 1992 series outlines how and why improvisation occurs in various musical traditions, from Indian classical music, to flamenco, the playing of an mbira, and of course, jazz. The TV show features what can only be described as a hardcore organ improvisation from the Sacre Coeur, high energy rehearsals of John Zorn’s COBRA game piece, George Lewis’s computer improvisation systems, video of Gaelic psalm singing, Chicago blues and Nashville country, Max Roach teaching schoolchildren to play drums, and an interview with Jerry Garcia. It is completely essential for anyone with even a passing interest in any and all forms of music. All four episodes are available on Ubu.

9. Derek Bailey & Min Tanaka – Music & Dance (1996)

This album, a collaboration with legendary Butoh dancer Min Tanaka, is a personal favourite. It is distinctive as a duo where you only hear one person’s playing, although Bailey insists in the sleevenotes that this music was made by two people. Tanaka is a dancer and choreographer, capable of expressing exquisite emotional extremes through movement, a member of a dance group called the Body Weather Laboratory who searched "for nature and freedom on both sides of the skin". He had a performance vocabulary that constantly changed, and Bailey found him a crucial influence. They performed together irregularly from 1978 onwards, with Music & Dance recorded in 1980. It unfurls for attentive listeners, revealing the swish and shuffle of Tanaka’s feet on the floor, and listen out for the moment in ‘Rain Dance’ where a torrential rain can be heard on the glass roof of the venue (which was a disused forge in Paris). A VHS of them performing together was released, but the clip on YouTube is filmed from behind Tanaka, so we cannot see his facial expressions, which will have been as important a part of the performance as Bailey’s fingers on the guitar strings.

10. Derek Bailey – Guitar Drums n Bass (1996)

This isn’t the best Derek Bailey track nor has it aged well, but it’s a crucial part of the picture and was a way into his work for many people in pre-internet decades, including Stewart Lee. Apparently, it wasn’t supposed to be like this – Bailey originally wanted to jam with the pirate radio DJs in his local area, but the idea ended up being watered down to a remote collaboration where Bailey played with pre-recorded productions by DJ Ninj. The space between Bailey and DJ Ninj is a chasm not broached, but its failure is less about drum & bass and free improvisation being a bad mix, and more that you can’t play together if you’re not sharing space or time. It comes off more a tasteless sandwich than an exciting stew, but it remains an important touchpoint in Bailey’s catalogue that is often dredged up. As far as playing with people outside the world of free improvisation and jazz, Derek & The Ruins is a much more successful explosion of sound.

11. Derek Bailey – Carpal Tunnel (2005)

Released on John Zorn’s Tzadik label six months before he died, Bailey’s motor neurone disease was initially diagnosed as carpal tunnel syndrome, which meant he was no longer able to hold a plectrum. Instead of giving up, he mapped the progress of the degeneration and tried to keep hold of his playing, with tracks named after the durations after diagnosis, recording three, five, seven, nine and 12 weeks after. By this point in his life, Bailey had long believed that improvisation had become calcified into genre, made pointless by its rigidity, and that its best years were passed, although predictably, this didn’t mean he stopped playing. The only way to hear samples is on AllMusic or at digital shops such as Boomkat which stock it as a download.