My tongue is edging only slightly towards the buccal mucosa of its neighbouring cheek when I write this. Everything has grown worse in Fugazi’s absence. It could be coincidence. And it isn’t entirely their fault. The pattern was set in motion by Reaganite neoliberalism, not to mention a series of seemingly unconnected prior occurrences. (Ask the documentarian Adam Curtis.) A few more post-hardcore records and string of all-ages concerts wouldn’t have prevented the inevitable calamities. Would they?

Still, I can’t help remembering Fugazi as a guiding hand which, in its own modest way, temporarily curbed the extremities which were unleashed in fuller force once the band, from 2003, rode off on indefinite hiatus.

Thereafter was unleashed a Pandora’s Box of lamentable events. Invasions. Bombings. Banking bailouts. Misinformation galore. Climate catastrophe. The main character syndromic individual taking precedence over the wider community or any semblance of a cohesive society. Preposterous masculinity. Library closures. Emo kids in KFC. Darren Grimes, not only existing but actually thriving in his own pipsqueak way. The banterisation of public discourse. Anti-intellectualism. People who just stand, moronically and with increasing frequency, right at the bottom (or top) of an escalator without foreseeing the problems it’ll cause for their fellow moving staircase passengers. Streaming giants, AI and other unrestrained tech developments denying countless talented people a career in the arts. Bigger bands lessening their shortfall by issuing seven colours of the same non-biodegradable vinyl. “Merchandise! / It keeps us…” alive? Kurt Cobain might’ve found convenience in GPS, as Helen Mirren insists with manic persistence. That same departed Fugazi fan would’ve been right mardy about the rest of this crap.

Formed in Washington DC in 1986/7, Fugazi were intentionally less sanctimonious than Ian MacKaye’s best known prior band, Minor Threat. Fugazi were more ambiguous, playful and stylistically freer; all major parts of their appeal. They also had compassionate ethical values which they expressed often and loudly (while being open to dialogue and not overly preachy), many of which now seem, if not dormant, then virtually extinct.

Sometimes Fugazi were criticised for telling people off, when their audiences moshed and whatnot. But these days selfish behaviour isn’t scolded enough, is it? Have you heard the racket in those recently rebranded “Quieter” train carriages? Ssh! Too authoritarian for you? It’s always been a fine line between that, and its opposite, while trying to figure out what’s easiest for everybody.

What was the one abstract noun left in Pandora’s Box when she slammed its lid closed? You know the answer. Not ‘cos of the education system, which is another thing that’s gone down the swanny, but from consuming salty snacks on an evening in front of QI. Hope? That’s right! Maybe it was misguided, in the first place, to locate this concept in the actions of Fugazi. “. . . don’t ask me why I obsessively look to rock & roll bands for some kind of model for a better society . . . I guess it’s just that I glimpsed something beautiful in a flashbulb moment once, and perhaps mistaking it for a prophecy have been seeking its fulfillment ever since.” So wrote Lester Bangs and he wound up dead at 33.

Where does this leave us? The hope that Fugazi might finally reform and rescue the Western World from its sorry state? Like Superman descending from the clouds to violently smack the smug chops of Lex Luther. (Or rather his badly drawn and edgelordin’ real-life equivalent.)

Hope?! Were they to reunite, Fugazi would feel more pressure than any act in history, including Bikini Kill, to do it in a dignified way consistent with the beliefs that once made them the respectable heroes of integrity. A lucrative slot at Coachella or Primavera, however well-attended, would undermine faith in the good name of Fugazi. No, it would have to be a tasteful three-consecutive-nights-at-the-Brudenell-Social-Club type of affair. Tickets would go within nanoseconds. Even then, the right-wing press would latch onto the event as the must-be-cancelled(post-haste!) comeback of these scruffily dressed progenitors of the woke mind virus. That alone, if I were Ian MacKaye, would be enough to keep me away from the flight cases. (Probably doesn’t use them, does he? Simply bundles all his equipment into a canvas satchel.)

‘Course I wouldn’t be writing any of this idealist, rose-tinted and logically flawed gabble-babble if the music wasn’t any cop. If any of their records had sounded like those of the reunited Refused or anything by England’s Worst Living Songwriter (initials F.T.), who are just two of the many admirers unfit to peck MacKaye’s tatty plimsolls, then Fugazi could have the kindest values in the world and I wouldn’t give a monkey’s. Fortunately, they were the full package.

Back in the 90s, Fugazi were known as the one band that all the more famous, yet creatively lamer, acts were so eager to be photographed next to and seen to be endorsing from on high. They acted like Italian gangsters at confession, that lot. Guilt-tinged and substance-addled sellouts who attempted, in vain, to cleanse themselves of their corporate sins and populist decision-making by, in the case of that naked bloke from RHCP, whacking a Fugazi sticker on the front of his cock-swabbed bass guitar.

The music! What about the music, man? All right, all right… MacKaye conceived the project as “The Stooges with reggae”. Other influences were dub, funk, metal, punk, pre-punk, post-punk, hip-hop, jazz, Captain Beefheart and more; all stewed in the pot before emerging as a nouveau dish altogether.

‘Suggestion’ from Fugazi (1988)

For a group that kept getting better and better, it’s ironic that Fugazi’s best-known song remains the opening one from their first EP. ‘Waiting Room’ is the tune most likely to be heard on the radio or in a club. That’s understandable as it rocks so hard, swingingly and infectiously. Instead, let’s highlight the EP’s powerful sixth track, ‘Suggestion’, which was written from the perspective of a woman who’s sick to the stomach of all the male harassment she has to suffer. Some felt MacKaye shouldn’t be putting words into others’ mouths. Fugazi rejected this by performing ‘Suggestion’ regularly in their concerts, right until the end, thus asking their (predominantly male) audiences to consider things from a female perspective – sometimes having fellow travellers such as Amy Pickering (Fire Party) take over on vocals. Too few people asked themselves this back then. Clearly too few do now, otherwise pathetic misogynist piggy grifters wouldn’t have secured such clout on the internet. The perspective shifts towards the end of the song: “We are all guilty.”

‘Promises’ from Margin Walker (1989)

Margin Walker was recorded in London at the end of a long European tour. It was conceived as an album but ended up as another EP which Fugazi viewed as “a documentation of exhaustion”. Drained from months of performing high-energy shows and sleeping in ghastly squats, their mood had worsened when America elected another Republican President, George H.W. Bush, immediately after Reagan’s reign ended. The EP has its moments in the hardcore tradition of soapboxing, such as the defence of political correctness on ‘And The Same’. Closing track ‘Promises’ is more cryptic and harder to pin down. The Joy Division-like music exacerbates the uncertain and, arguably, despairing nature of the lyric. Addressing the emptiness of promises (specific ones, or as a rule?) and the inadequacies of language (“stupid fucking words”), MacKaye could be suggesting that, as change is an inevitable part of growth, we all end up as hypocrites, given long enough. There’s another passage where he might be questioning whether we even have free will at all. This was seriously less absolutist than hardcore. Best append it with a “post-”, then.

‘Blueprint’ from Repeater (1990)

By 1990, Picciotto’s role in the band had extended from lively co-vocalist to second guitarist as well. Here Fugazi came into their own. Over Canty and Lally’s unbeatably tight and inventive rhythm parts, MacKaye and Picciotto were free to riff, spindle, skree, tap, harvest feedback, stop & start, interplay, anti-play, hack and chop. It’s difficult to highlight one anthem from an album packed with Fugazi calling cards. ‘Turnover’, the title track, ‘Merchandise’, ‘Reprovisional’, ‘Shut The Door’ and the rest all helped establish the group’s, well, blueprint. Let’s plump for ‘Blueprint’, then, as it’s basically Repeater’s centrepiece. After a soft and tension-building intro comes the first incarnation of the incendiary chorus. The opening lyrics (“I’m not playing with you / I’m not playing with you…”) sound a bit like Picciotto has fallen out with someone who’s been bullying him at nursery school. Turns out it’s more a rejection of corporate greed and mindless consumerism, suggesting it would healthier to find one’s own path and think for yourself instead.

‘Reclamation’ from Steady Diet Of Nothing (1991)

In Joe Gross’ (essential) book on 1993’s In On The Kill Taker, Fugazi’s preceding album is presented as a low point before the triumphant apex. That’s useful for narrative purposes. (I should know. I’ve written a book about Paul McCartney in the 1990s which suggests the ex-Beatle’s work wasn’t up to scratch in the previous decade. As we all know deep down, Macca has always been brilliant, he always will be, and ‘The Frog Chorus’ is sublime.) The truth is that each Fugazi album surpassed the last. The band had issues with Steady Diet Of Nothing’s supposedly dry and flat sound. They and their listeners recognised the songs were up to scratch, though, especially as they still succeeding in slapping live. Take concert staple, ‘Reclamation’. The warm bassline provides the groove. The quieter, almost spoken verses are interrupted by explosive guitar-noise crescendos. It has a political edge (as it’s a pro-choice lyric). The chorus is anthemic and easy to remember, because it’s just one word that’s also the song title. It climaxes with MacKaye shouting his head off. Production. Schmuction.

‘Rend It’ from In On The Kill Taker (1993)

Fugazi are in the minority of artists who worked with engineer Steve Albini and disliked the results. Intending to record a couple of songs, they lay down 12 over three days and came away thinking it was the greatest session of their lives. A few days later, Albini agreed with each member that it hadn’t cut the mustard. They’d been having too much fun. Fugazi reconvened with Repeater producer Ted Niceley who captured the magic instead. Those who don’t believe Fugazi improved exponentially might point to In On The Kill Taker as the band’s pinnacle. It’s definitely a suitable entry point for newcomers. Further evidence that Fugazi were often dissatisfied with their own performances, Picciotto felt he never succeeded in making ‘Rend It’ “perfect” in concert and says he “can’t stand” the album version. Niceley, on the other hand, called it “a masterpiece… an opera… a very romantic song”. Its intro is particularly thrilling. The clattering opening cuts out abruptly for Picciotto’s fraught acapella. The music returns in a deceptively lowkey fashion, building anticipation for the rowdier chorus that’s lurking in wait.

‘Target’ from Red Medicine (1995)

Four albums in and Fugazi continued to push themselves by keeping their ears open to fresh influences, using their instruments in different ways and occasionally introducing new ones as well. (‘Version’ has clarinet on it.) For the still frequently raucous Red Medicine, Fugazi got (even) dubbier, jazzier and maybe a touch more psychedelic. As countless reviewers have posited, the album’s key line appears on the Picciotto-sung ‘Target’: “…and I realize that I hate the sound of guitars”. This responded to the alt-rock boom of the early 90s for which Fugazi were, whether they liked it or not, partly responsible and it laments the coopting of the underground. It doesn’t need repeating that Fugazi remained steadfastly independent. While they did attract some attention from major labels, signing to one of the big boys was never a consideration. “It would have been the most stupid and self-destructive thing we could possibly have done,” said Picciotto.

‘Pink Frosty’ from End Hits (1998)

At the time, there was concern that End Hits’ title amounted to a letter of resignation. That wasn’t the case, for the time being. Perhaps some wished it was. The album was criticised for its lengthy passages of experimentation and lack of memorable shout-alongs. Andy Kellman of the AllMusic website has called tracks seven-to-nine “the worst stretch of material Fugazi have recorded, full of disjointed patches and awkward moments.” Fiddlesticks! As we’ve established, Fugazi kept getting better and End Hits was simply the latest zenith of their working methods and evidence of their increasing versatility. The group always said they never “wrote” songs. The music was assembled, as a collective. It was often disassembled, too, then resculpted radically before completion. End Hits has fiery moments (much of ‘Place Position’; all of ‘Five Corporations’). It’s packed, too, with strange and abstract passages which some fans found challenging or meandering. They also verify Fugazi as one of the great (and largely unrecognised) post rock bands. In 1994, Simon Reynolds defined post-rock as “using rock instrumentation for non-rock purposes”. On End Hits’ non-rocking penultimate track, ‘Pink Frosty’, it’s as if Fugazi were trying to deconstruct themselves back down into virtual silence.

‘I’m So Tired’ from Instrument Soundtrack (1999)

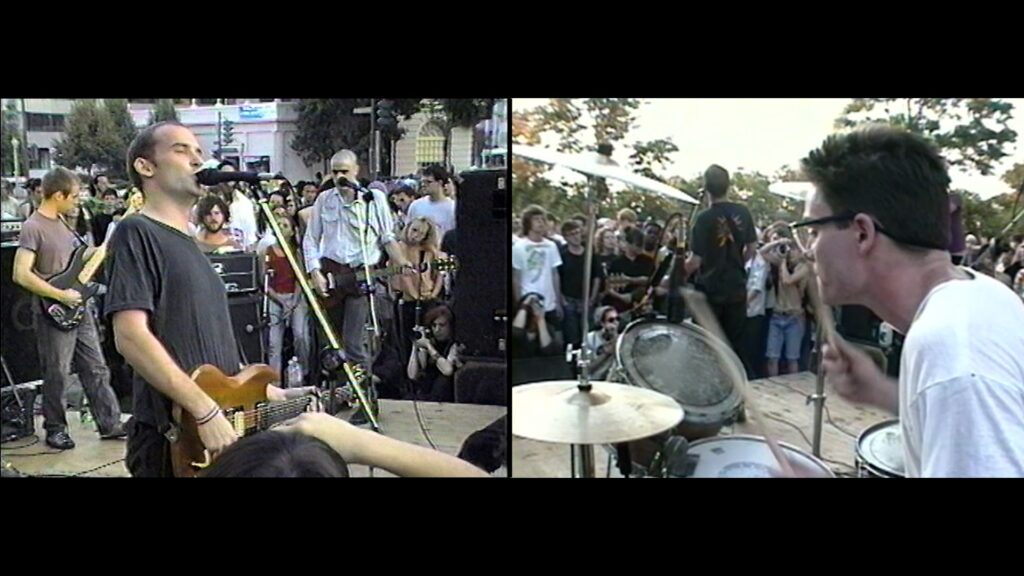

Jem Cohen’s Instrument film is a less a documentary in the traditional sense than tons of Fugazi-based clips, varying in quality and value, strung together into two hours of… something. The accompanying “soundtrack” disc features demo run-throughs, outtakes and other scrappy material. It’s the Fugazi “album” that sounds least like their other releases. You could also say ‘I’m So Tired’ is the Fugazi song that sounds least like Fugazi. It’s a ballad sung by MacKaye and performed on the piano. Basically, it’s their equivalent of ‘Avril 14th’ by Aphex Twin. This distinctly uncharacteristic song is one of their most-played tracks on Spotify. Hang on… Fugazi allow their music to appear on Spotify?! Sort it out, you complicit opportunists!

‘Furniture’ from the ‘Furniture’ single (2001)

Fugazi’s greatest and final work, The Argument, was accompanied by a single which hosted no songs from the album. Two of them, ‘Hello Morning’ and ‘Furniture’, were resurrected older compositions. The latter had appeared way back on the band’s first demo. The scorching instrumental, ‘Number Five’, had its roots in Instrument’s calmer ‘Turkish Disco’. Fugazi were always prone to leaving ideas on the shelf and reaching for them when the time was right to fashion something interesting out of them. With hindsight, however, as a fairly frantic single which harks back to their roots, ‘Furniture’ has a sense of going full circle, thereby indicating that the end (hit) might well be nigh.

‘Epic Problem’ from The Argument (2001)

In 2001 The Argument seemed like the latest leap forward in Fugazi’s creativity. Alas, it turned out to be the culmination. Hopes that it would be followed by MacKaye and co.’s equivalent of the “White Album” were dashed when the band went on hiatus after touring The Argument. As what’s known as “life stuff” prevented Fugazi from maintaining their working regime of practising five hours a day, five times a week, they could no longer commit to giving their audiences 100 percent. Phoning it in would not be an option. So that was that. What a way to go, though. Some of the catchiest melodies they’d ever sung (or shouted), sometimes harmonised with the guest vocals of Bridget Cross or Kathi Wilcox. The deft use of the most suitable orchestral instrument for rock purposes (cello). All the mightiest bands have two drummers for at least one spell of their career and here Jerry Busher plays second drumkit or extra percussion on most of the record. None of this augmentation tamed Fugazi’s jerky aggression. It’s their masterpiece. The verses to ‘Epic Problem’ resemble the content of a telegram. “We regret to inform,” yells MacKaye…

“Stop.”

WE ARE FUGAZI FROM WASHINGTON D.C. is screening in the UK and ROI now through Spring