Ahead of this year’s Counterflows festival which features music and talk dedicated to him, we look at the work of Ahmed Abdul-Malik

Peruse any list of post-war jazz greats and it’s unlikely you’ll find Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s name included. Yet, for around a decade, from the mid-1950s onwards – and particularly across the six albums he cut as a bandleader between 1958 and 1964 – he was a unique and powerful presence whose visionary music was both forerunner and catalyst to some of the jazz’s most radical departures.

An accomplished double-bassist who worked with several of the top be-bop and hard-bop players of the day, he was also a virtuoso player of the oud – the short-necked, pear-shaped lute ubiquitous in Arabic music – and pioneered its use in jazz settings. Far from being just a gimmick, it was a key part of his sincere drive to incorporate the instrumentation and modes of Middle Eastern and North African music into American jazz.

This, in itself, was a facet of his own deeply-felt desire to connect with the cultural and spiritual foundations of the pan-Islamic world and create a modern form of devotional music that could speak to Black Americans. The fact that, at the time, his art was often dismissed as mere kitsch orientalism speaks volumes about a mainstream – largely white – critical establishment that recoiled from and sought to sideline manifestations of Black Nationalism and Islamic identity.

In 1963, he told Down Beat magazine: “People think I am too far out with religion… How can you play beauty without knowing what beauty really is? Understanding the Creator leads to understanding the creations, and better understanding of what you play comes from this.”

Born in Brooklyn in 1927, Abdul-Malik launched his career as a professional bass player in 1944 while still in High School and, within a few years, found himself at the heart of New York’s be-bop scene. Yet, even at this early stage, he stood apart from his colleagues, speaking fluent Arabic and already experimenting with instruments such as the oud and the zither-like kanoon. To anyone who asked, he explained that his father had come to the U.S. from Sudan and that he’d grown up surrounded by the sounds of the Arab world.

But the truth was more complicated – and the result of a profound transformation in the great American tradition of personal reinvention. In reality, Abdul-Malik was born Jonathan Tim Jr. to parents who had emigrated from St. Vincent in the Caribbean. While studying at New York’s High School of Music and Art, he immersed himself in the vibrant cultural diversity of 1940s Brooklyn and took lessons from Syrian and Lebanese musicians, while connecting with musicians from West Africa. It was during this time that the young Jonathan Tim converted to Islam and took the name Ahmed Abdul-Malik.

In this respect, he was part of a radical trend among the most forward-thinking Black intellectuals of the day. In the same way that be-bop was conceived as a concerted effort to reclaim jazz from commercial swing bands and reassert it as an avant garde Black art form, in the mid-to-late 40s, many notable musicians gravitated to Islam as a rejection of oppressive white culture embodied in Christianity.

Several of them were particularly drawn to a messianic strain of Islam known as the Ahmadiyya movement. Among them were saxophonists Yusef Lateef (formerly William Evans) and Sahib Shihab (Edmond Gregory), drummer Art Blakey (who was briefly known as Abdullah Ibn Buhania) – and Abdul-Malik. Followers were encouraged to turn away from the drugs and alcohol endemic in jazz circles, drop their ‘slave names’ and perceive themselves not as part of a Black minority but a wider Islamic world.

By the mid-50s, Abdul-Malik had worked as bassist with an impressive roster of jazz artists including Blakey, saxophonists Don Byas and Coleman Hawkins and his childhood friend, pianist Randy Weston. At the same time, his interest in Arabic music had continued to deepen, as he studied the oud with serious intent and forged links with New York’s Arab music community. His dream was to find a way of fusing these two musical worlds, but opportunities to perform the music he envisaged were thin on the ground.

He later reflected: “I couldn’t find no place to work so I can try these things out. Believe me, they thought I was out of my mind.”

A decisive turning point came in 1957, when Abdul-Malik was hired for a high-profile, five-month residency at the famous Five Spot Café jazz club in the East Village as bassist in pianist Thelonious Monk’s quartet. There he met John Coltrane, then tenor sax player in Monk’s quartet, who deeply dug Abdul-Malik’s conception of Arab-influenced jazz. With earnest encouragement from Coltrane and Monk, Abdul-Malik set about forming his first Arab-jazz fusion ensemble in late 1957.

This ground-breaking group featured Abdul-Malik on bass and oud, Syrian-American violinist Naim Karakand, kanoon player Jack Ghanaim, Mike Hemway on the darbuka hand drum and Abdul-Malik’s Brooklyn neighbour and old friend Bilal Abdurahman on various reed instruments. Something entirely new had just been born.

Thelonious Monk Quartet – ‘In Walked Bud’ from Misterioso (1958)

Even as Abdul-Malik’s daring fusion experiment was getting off the ground, he still had one foot planted in jazz. In summer 1958, he was hired for another long engagement with Monk’s quartet at the Five Spot, completing the rhythm section with drummer Roy Haynes, and with Johnny Griffin replacing Coltrane on the tenor. Several tracks recorded in August were presented on Monk’s live album Misterioso. The effervescent ‘In Walked Bud’ is classic Monk. Beginning with the pianist’s jauntily disjointed opening statement, it features a tightly coiled yet mellifluous solo from Griffin followed by a gloriously awkward, ineffably swinging solo from Monk. Abdul-Malik holds a rock-steady walking bass line, peeling off to take a solo with a cheekily Oriental motif appearing about 40 seconds in. The album, released on Riverside, brought Abdul-Malik to a wide audience – and helped Monk to persuade the label to take a chance on recording Abdul-Malik’s band.

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Ya Annas (Oh, People)’ from Jazz Sahara (1958)

The result was Jazz Sahara, Abdul-Malik’s debut and the first recorded glimpse of Arab-jazz. Featuring his regular group plus jazz drummer Al Harewood and Monk band-mate Griffin, the album contains four originals by Abdul-Malik, each of them related to a specific maqam or Arabic mode. On ‘Ya Annas (Oh, People)’, oud, kanoon and violin navigate a unison melody in the style of Egyptian folk over loping hand-drums in a traditional 3/4 rhythm, followed by a microtonal violin solo, a delicate passage on kanoon and a smoky statement from Griffin. Then, at around the seven-minute mark, there’s a change of gear as the drums kick in, signalling a shift into an irresistible 4/4 swing with Abdul-Malik slotting into a nippy jazz bass vamp, eliciting a puckish solo from Griffin. Here, Abdul-Malik’s concept can easily be heard as a predecessor of Joe Harriott and John Mayer’s Indo-jazz innovations that followed almost a decade later.

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Takseem (Solo)’ from East Meets West (1960)

For his follow-up album, recorded the following year, Abdul-Malik beefed up the horn section, adding a cadre of hard-bop heavyweights: Lee Morgan on trumpet, Benny Golson on tenor sax and Curtis Fuller on trombone, plus Jerome Richardson on flute. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this expanded ensemble tugged the music closer to hard-driving jazz on a few tracks. But the standout piece jettisons the jazzers entirely, allowing the core group (with Ahmed Yetman taking over kanoon duties) to luxuriate in their most explicitly Arabic-influenced tune so far. Taken at a slower pace, with clopping hand drums and an implacable, deep bass plod, ‘Takseem (Solo)’ features the sensuous vocals of Jakarawan Nasseur. Yearning violin and rippling kanoon take turns responding to Nasseur’s seductive exhortations as she allows her voice to slide around the notes with loose, microtonal languor, creating a thick fug that’s intoxicating and startling in equal measure.

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Nights On Saturn’ from The Music Of Ahmed Abdul-Malik (1961)

Ever restless, Abdul-Malik effected a shift away from the Arabic sound with 1961’s The Music Of Ahmed Abdul-Malik, crafting an album that mixed the accessible with the avant garde. Bilal Abdurrahman is the only original group member in attendance, joined by trumpeter Tommy Turrentine, tenor man Eric Dixon, cellist Calo Scott and young drummer Andrew Cyrille, still a few years away from joining the Cecil Taylor Unit. In this new setting, Abdul-Malik explores calypso, jazz ballad (with Scott taking an aching turn on ‘Don’t Blame Me’) and the blues, showcasing his own growing instrumental prowess on ‘Oud Blues’. ‘Nights On Saturn’ is the showstopper, though. Over a weightless drum skip and insistent bass throb, Abdurrahman takes an astonishing solo on an ancient Korean reed instrument called a peri, sounding remarkably like a North African double-reeded rhaita or a Turkish zurna. Unmoored and exploratory, it proves that Abdul-Malik was fully hip to the emerging possibilities of free jazz.

John Coltrane – ‘India’ from The Complete Village Vanguard Recordings 1961 (1961, released in 1997)

After their initial encounters in Monk’s band, Abdul-Malik and John Coltrane remained friends. In fact, Coltrane had been Abdul-Malik’s first choice as saxophonist on his early sessions but Coltrane’s commitments to Miles Davis’s group scuppered that plan. The opportunity to collaborate finally arose in November 1961 when the saxophonist asked Abdul-Malik to sit in on one of the sessions recorded by Impulse! for 1962’s Coltrane “Live” at the Village Vanguard. This take of Coltrane’s raga-inspired ‘India’ (which languished in the archives until 1997) features Abdul-Malik strumming a tambura at the beginning (erroneously credited as an oud). Abdul-Malik is off-mic and quickly drowned out by Elvin Jones’s bullish polyrhythms – but it remains a notable encounter. Here, he contributes essential energy to an embryonic stage of Coltrane’s obsessions with non-Western music and spirituality – a seed that eventually reached full-bloom in recordings such as Alice Coltrane’s tambura-drenched spiritual jazz classic ‘Journey In Satchidananda’.

Odetta – ‘Yonder Comes The Blues’ from Odetta & The Blues (1962)

Described by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as “The Queen of American Folk Music,” singer and Civil Rights activist Odetta was a key figure in the folk music revival of the 1950s and 60s. On albums such as 1957’s Odetta Sings Ballads And Blues, she interpreted traditional folk songs, spirituals and blues, accompanying her own booming voice with simple acoustic guitar arrangements. In the early 60s, she expanded her musical palette, releasing albums – such as 1962’s Odetta & The Blues – that used jazz instrumentation. Here, Abdul-Malik holds down the bass on her high-spirited version of another traditional blues, in a band that revels in a slow-marching New Orleans sound. Buck Clayton’s trumpet and Vic Dickenson’s trombone parp and buzz with lascivious cheer and plenty of mute, while Abdul-Malik relaxes into a laid-back, contented stroll.

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Suffering’ from Sounds Of Africa (1962)

At the end of 1961, Abdul-Malik visited Nigeria and absorbed the local music and culture. Back in the studio in August the next year, he converted his discoveries into new sounds with a bigger band, adding trumpet and saxes. The main development, though, was the addition of two extra percussionists, Montego Joe and Chief Bey, both of whom had recorded with Nigerian master percussionist Babatunde Olatunji. Tracks like ‘African Bossa Nova’ and the happy calypso ‘Wakida Hena’ are frothy, upbeat affairs but ‘Suffering’ is the dark heart of the date: a skeletal, percussion-heavy jam with an insistent, repeating sax riff and tendrils of cello and flute rising like wisps of smoke in the Lagos night sky, while the trumpet spits out insolent cries, the bass thrums up a chain-gang trudge and vocal chants echo the tragedy of slavery. Saying so much with so little, it’s an exercise in stark economy.

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Summertime’ from The Eastern Moods Of Ahmed Abdul-Malik (1963)

Abdul-Malik convened his smallest ensemble for 1963’s The Eastern Moods Of… – a trio with William Henry Allen on percussion and Bilal Abdurrahman on reeds. In some respects, it was a return to his original oud-centric experiments in Middle Eastern and North African sounds: ‘Magrebi’ picks up the Egyptian folk style of Jazz Sahara, and ‘Shoof Habebe’ is a lilting interpretation of Somali sacred music. But there’s innovation here too, with ‘Sa-Ra-Ga’ Ya-Hindi’ offering a simulacrum of Indian raga with a bowed cello drone and the oud’s precisely bent notes imitating a sarod. Most surprising, however, is a spare and haunting rendition of Gershwin’s ‘Summertime.’ Allen rolls out an unobtrusive bongo beat over which Abdul-Malik lays lushly plucked bass. The joker in the pack is Abdurrahman, who takes three unhurried solos – sweetly loquacious on clarinet and alto sax while on Korean peri he keens and squirms like a strangulated bagpipe.

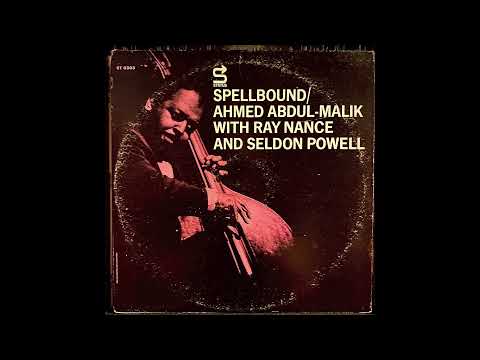

Ahmed Abdul-Malik – ‘Song Of Delilah’ from Spellbound (1964)

For his final album as a leader, Abdul-Malik pulled off a clever inversion. For the first time, he recorded a set composed entirely of jazz tunes, hiring violinist Ray Nance, pianist Paul Neves, drummer Walter Perkins and saxophonist Seldon Powell – as well as Sudanese oud player Hamza El Din. Rather than asking American musicians to make Middle Eastern music, he now plunged a master of Arabic music into a jazz setting. For the most part, on standards like ‘Never On Sunday’ and ‘Body and Soul,’ the two cultures don’t quite meld, with the Americans tending to play over El Din. But, on ‘Song Of Delilah’ something magical happens as the ensemble drops down to hushed vamp allowing El Din to take a short but sublime solo that displays a breath-taking mastery of his instrument. If Abdul-Malik had intended to prove that the oud could thrive in a jazz context, he achieved it here.

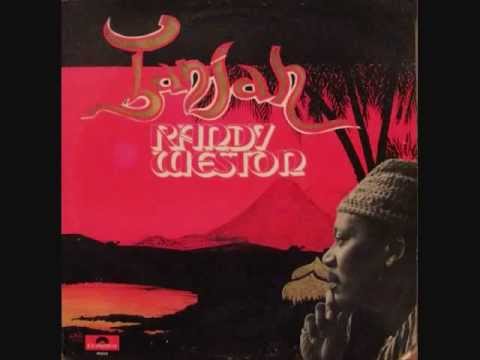

Randy Weston – ‘Tanjah’ from Tanjah (1974)

With his last two albums selling poorly, and invitations to record becoming scarce, Abdul-Malik began to invest his energies in education, first in his local Brooklyn community and later at New York University, where he taught jazz improvisation until suffering a stroke in the 1980s. After this he returned to his own studies, taking lessons from Palestinian-American oud player Simon Shaheen, until a second stroke in 1993 ended his life at the age of 66. This track, a rare later sideman appearance recorded in 1973, stands as a suitable epitaph, on which he’s reunited with pianist Randy Weston, with whom he’d made his recorded debut back in 1956. Weston, too, was a seeker who, since the beginning of the 60s, had been incorporating African elements into his music. Here, he builds a bright township hop with thick percussion and gleaming horns leaving room for a brief but full-bodied oud solo from Abdul-Malik. While his work still doesn’t receive the widespread acclaim it deserves, performances like this seal his status as a master musician for the ages.

AHMED, featuring Pat Thomas, who rework the music of Ahmed Abdul-Malik play this year’s Counterflows festival, and also feature in a panel discussion with Edward George