Post-punk was an evolution, not a revolution. There was no real starting point. That is the true beauty of post-punk; it eschews easy beginnings and tidy endings. It is a story with ragged edges. It grew out of the charred corpse of that which preceded it, taking root in the art schools and squats of the late seventies. It began in the wake of a seismic shift, or a simple opening of a door. Where the British and American urban centres resonated dangerously with the increasingly articulate sounds of a disenfranchised youth desperate to be heard, the Irish mutation happened almost in secret. We hear about it only in retrospect, a vague, non-committal nod thrown in its direction every time another history of U2 gets written.

Right now though, things are a little different and the reason for that is the recently-released Strange Passion compilation, helpfully subtitled as Explorations in Irish Post Punk, DIY and Electronic Music 1980-83. Released on Finders Keepers sub-label Cache Cache and curated by local promoter, DJ and record collector, Darren McCreesh, this 14-track compilation aims to unearth the forgotten and hidden gems of the early Irish post-punk scene. The results are linked more in spirit than aesthetic, something which McCreesh reckons stems from the isolation and frustration of working on this side of the Irish sea.

“There was a feeling that England and America were much more culturally advanced than we were, which they were because Ireland back then was in lock-down,” he says. “It was very conservative, very catholic, very depressed. That much I do remember; I was only six when all this kicked off but I do remember the hunger strikes, the edginess, the tension, the feeling that there was nothing really here for people.”

While listeners might be more familiar with the Clannad, Planxty or even Mellow Candle records coming out of Ireland in the late seventies, it was the first rumblings of an angrier youth that piqued the interest of Finders Keepers founder, Andy Votel.

“I knew there must have been more protest, more attitude, a more destitute side of things that would have come out in the late ’70s and early ’80s,” says Votel. “Bands like The Threat and Chant! Chant! Chant!, they’re almost like Persian records because they’re almost mythical! Do these bands even exist?”

In the end, a collection of singles, demo tapes, radio sessions and unreleased takes make up the fourteen tracks. They run the gamut of the post-punk impulse, from the re-calibrated pop of Belfast’s Dogmatic Element, through the anger of the Virgin Prunes and The Threat and on to the DIY electronic explorations of Operating Theatre and SM Corporation. McCreesh sees the acts as a group of people involved in “helping to broaden the Irish identity which was quite narrow up to that point.”

This nascent anger and rebellion found its most well-known manifestation in The Virgin Prunes, an act that McCreesh points out as an example of the inarticulate but passionate form this anger took. “If you listen to the Virgin Prunes, the Virgin Prunes are very, very angry,” he says.

“It comes across in the music. It’s almost like an embryonic self-expression, it’s bursting through. Lyrically it wasn’t quite there but I think that’s how it came across, how it expressed itself within the Irish scene.”

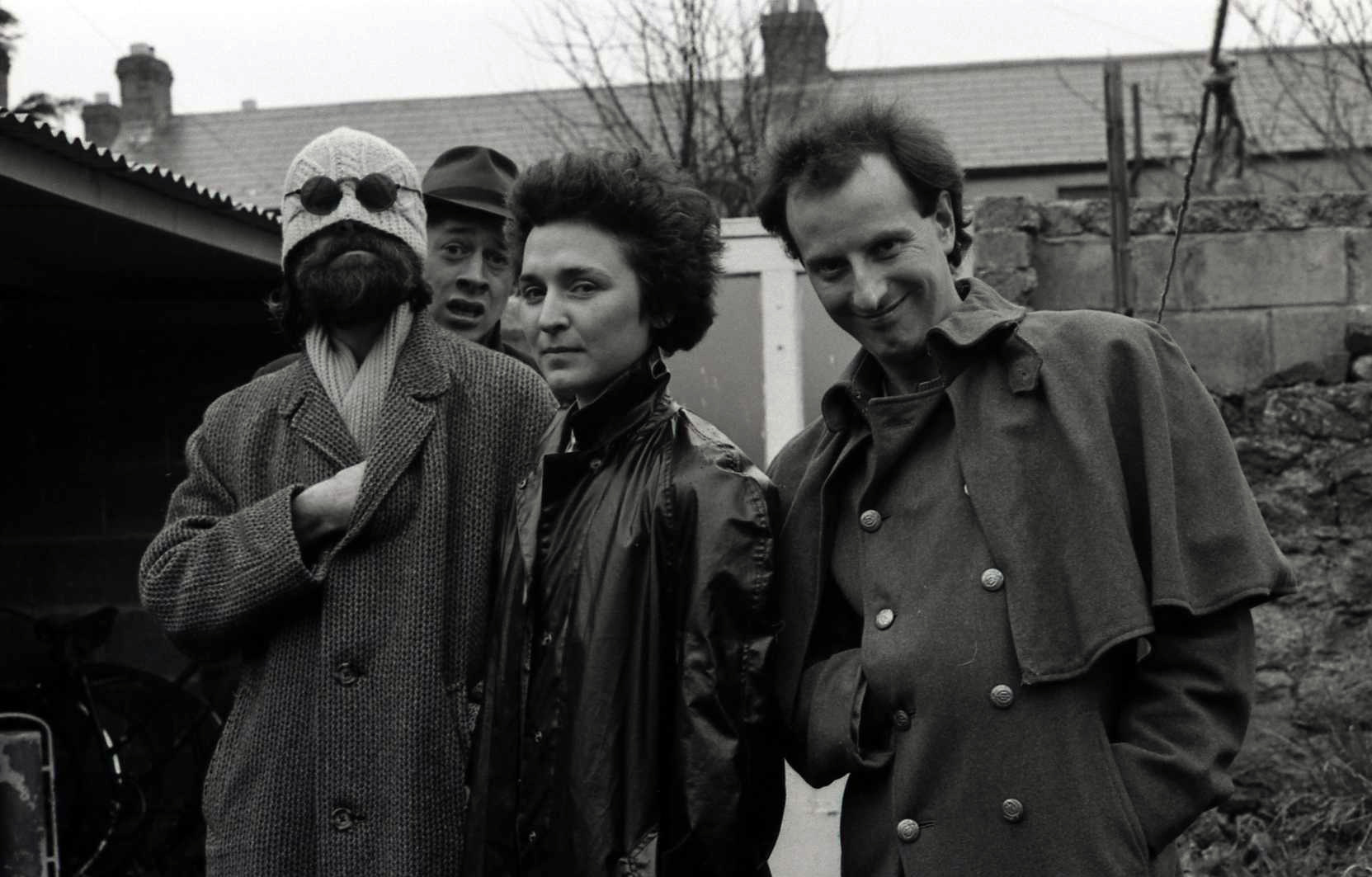

Operating Theatre

Steve Averill of SM Corporation played with the Virgin Prunes when they supported The Clash in Dublin, a set cut short after just three songs as the crowd threatened to bottle the band off stage. “I have a lot of respect for the Prunes because they really took things to certain limits,” he says. “They were just the most confrontational. In many ways, they were more punk than most of the punk bands that came before them and it was more about sexual politics than politics of the nation because these guys were in dresses and make-up and the whole thing.”

Averill’s own band, featured twice on the compilation under the SM Corporation name, were one of the first punk-driven groups in the country to adopt synthesizers and electronics into their work, moving from experimental, long-form improvisation to a more pop-structured form which would eventually lead to an appearance on RTÉ’s flagship Late Late Show, the most popular television program in the country. While a rough dictaphone recording of that appearance exists, they are represented on the compilation by two unreleased demos; one a minute-long jingle for a Switzers radio ad campaign, the other a three-minute slice of electro-pop perfection. The latter, ‘Fire From Above’, has aged very well, fitting snugly with the John Carpenter-loving aesthetic of the Italians Do It Better crew.

The other leading light on the electronic frontier was Roger Doyle and his Operating Theatre project with Olwen Fouéré. While Doyle was an experienced electro-acoustic composer working in academic circles, Operating Theatre was his first go at the pop format and the results are beautiful. “It was all new to me”, says Doyle. “’Austrian’ was the very first thing I’d ever done with pop music so I was very much a learner, very much new to it. I have to say I didn’t think of it as punk at the time. It was a single with CBS records in the summer of ’81. It was on the radio a bit but it only sold about 300 copies. At the time it seemed kind of pathetic.”

How those sales compare to the 30 cassette copies of Tripper Humane’s battered electro track ‘Discoland’ is another matter entirely.

While SM Corp, Operating Theatre and Tripper Humane were a world from loud guitars and angst-ridden vocals, they highlight a broadening of vision amongst musicians in Ireland and a willingness to get things done themselves. This DIY spirit was key to everyone I talked to. Brian McMahon of Dundalk’s proto-synth-poppers Choice put it succinctly when he said, “the DIY spirit of punk inspired people to pick up instruments and create music. Previously we thought you had to be some kind of musical virtuoso.”

This simple spark of creation set fire to the imaginations of many young musicians around the country, including Eoin Freeney, vocalist in Chant! Chant! Chant!. “It was time to make our music and find our sound,” he says. “There was a lot of freedom.”

“Some of the songs, just for us, were always about how nothing was to be left out, everything was possible. Even if you don’t play an instrument per se, just bring the idea. It was just about making music, it was never about anything else.”

The influence of British television, radio and magazines was huge among the stimulation-starved kids in Dublin and beyond, with names like John Peel, Paul Morley and Julie Burchill being just as important here as they were at the other end of the ferry. Still, the disconnect between British and Irish culture meant that people here were often left to figure things out for themselves. “The fact there was a sea between us,” says McCreesh, “meant that it was all at a remove, there was an exoticism to it”.

Andy Votel puts it in culinary terms. “The thing is, if you imagine DIY in the UK or America, it’s all good to do it yourself, but the cultural comfort zone has already been done,” he says. “Half the job is sorted. It’s similar to a ready-made trifle, all you have to do is sprinkle the toppings! It’s like decorating a ready-made cake in the UK but in Ireland it’s like you have to make the whole cake and you might be making the cake out of custard and curry powder because you have to be creative! That cultural comfort zone exists in England and America but it doesn’t or didn’t exist there.”

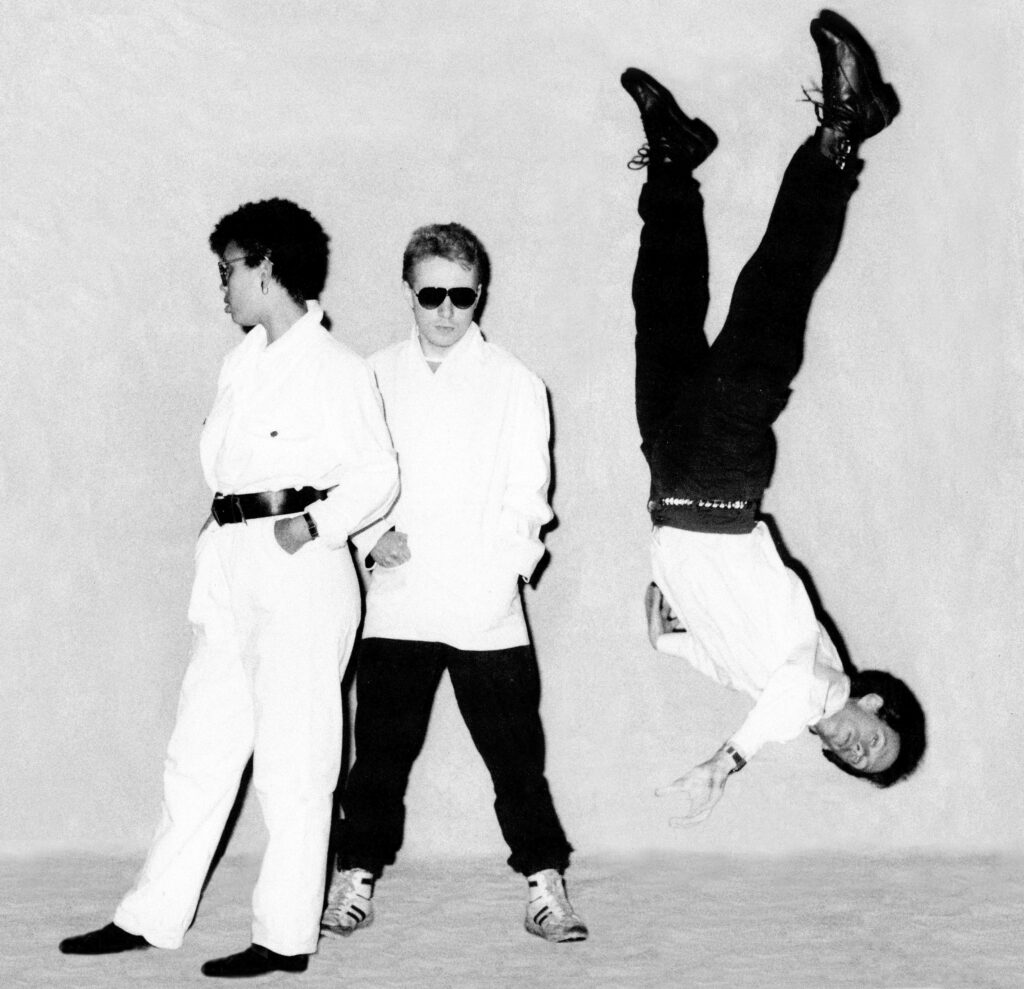

Major Thinkers

By the early 80s, a framework of support had begun to appear for this alternative music, with zines and magazines like Vox, Heat, Jump and Too Late combining with a wave of radio presenters interested in new sounds. “I think what you had in the 80s was, you had a much more unfiltered attitude towards presenting culture,” says McCreesh. “People were taking risks, they weren’t having material shovelled down their throats. Producers seemed to have a greater handle on what was happening at grass roots level.”

“The precursor to 2FM, RTE Radio 2 had just been set up in response to pirate radio stations and through that, new blood like Ian Wilson was being brought on board to produce these new radio programmes. So you had this new station and new blood who were schooled in punk and John Peel.”

While the British influence on Strange Passion is strongly felt, the feel of American punk and it’s funkier outgrowths also made a distinct impression. “It’s very apparent on Major Thinkers,” says McCreesh of the Wexford band who emigrated to New York in the early 80s. “If you listen to the percussion [on ‘Avenue B’], it could only have come from New York. It was actually recorded in New York.”

Brian McMahon also points out the influence of disco on Choice. “I wouldn’t underestimate the New York influence,” he says. “Television, for example, were an influence on The Scheme, a pre-Choice group from ’79 that featured Ciaran and myself from Choice and Ciaran’s brother Brian Vernon. NYC disco like Sylvester and Chic and the likes was also a big influence, especially for our bass-lines and drum machine patterns.”

While the scene – for want of a better word – in Dublin was left pretty much alone for the early 80s, an influx of record company A&R men in the wake of U2’s success had a divisive effect on the bands here. While bands like SM Corp, The Virgin Prunes and Chant! Chant! Chant! were friends with or played with U2, they didn’t exactly feel like following in their compatriots’ footsteps towards global super-stardom/domination. Choice, for instance, didn’t even have a phone between them, never mind a manager. The same was not to be said for others however and this was one reason McCreesh set 1983 as the limit for this project.

“It does seem to be the case that there was a golden period between ’80 and ’83,” he says. “It’s very much the case that when U2 broke though and you had this influx of UK A&R men, a lot of bands decided that if we’re going to break out of this cycle of unemployment and not having any money, maybe we have to give these people what they want to hear, which was basically a carbon copy of U2.”

“I think around the mid-80s, when U2 were breaking through or after they had broken through, you probably had a lot more managers begin to come on the scene and help bands manage their careers, in the sense that you could have a career.”

Steve Averill saw similar trends, though as someone familiar with the music industry from his time in the Radiators From Space, he took it all with a pinch of salt and carried on doing what he’d been doing anyway. “People forget about what bands were around because the vast majority of bands were funnelling this U2 kind of rock, like Cactus World News and these bands who were getting signed,” he says. “Whereas on the fringes, there was always this kind of experimentation going on. No labels were interested in it over here, none of the local labels were vaguely interested in what they were doing.”

“The weird thing was I remember distinctly, about six months after we broke up, people like Yazoo were suddenly having top ten hits and we got a letter from one of the record companies saying ‘Oh, we remembered your tape from when it came in and now we think it could be really good’. But at that stage it had all disappeared and fallen apart so we just broke up.”

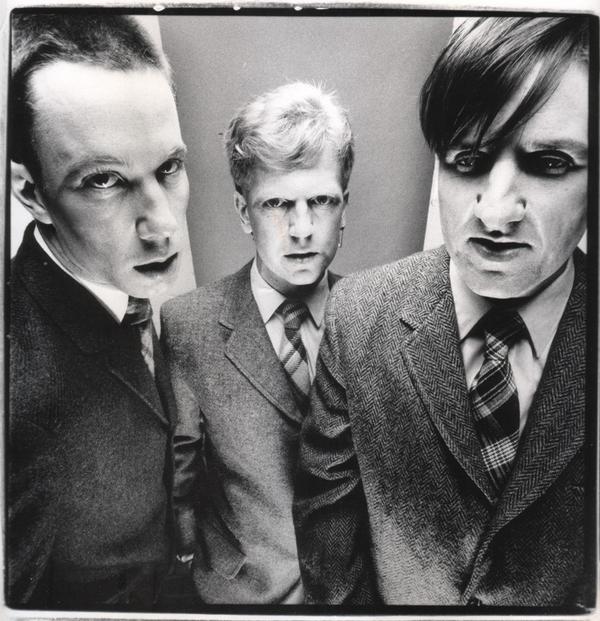

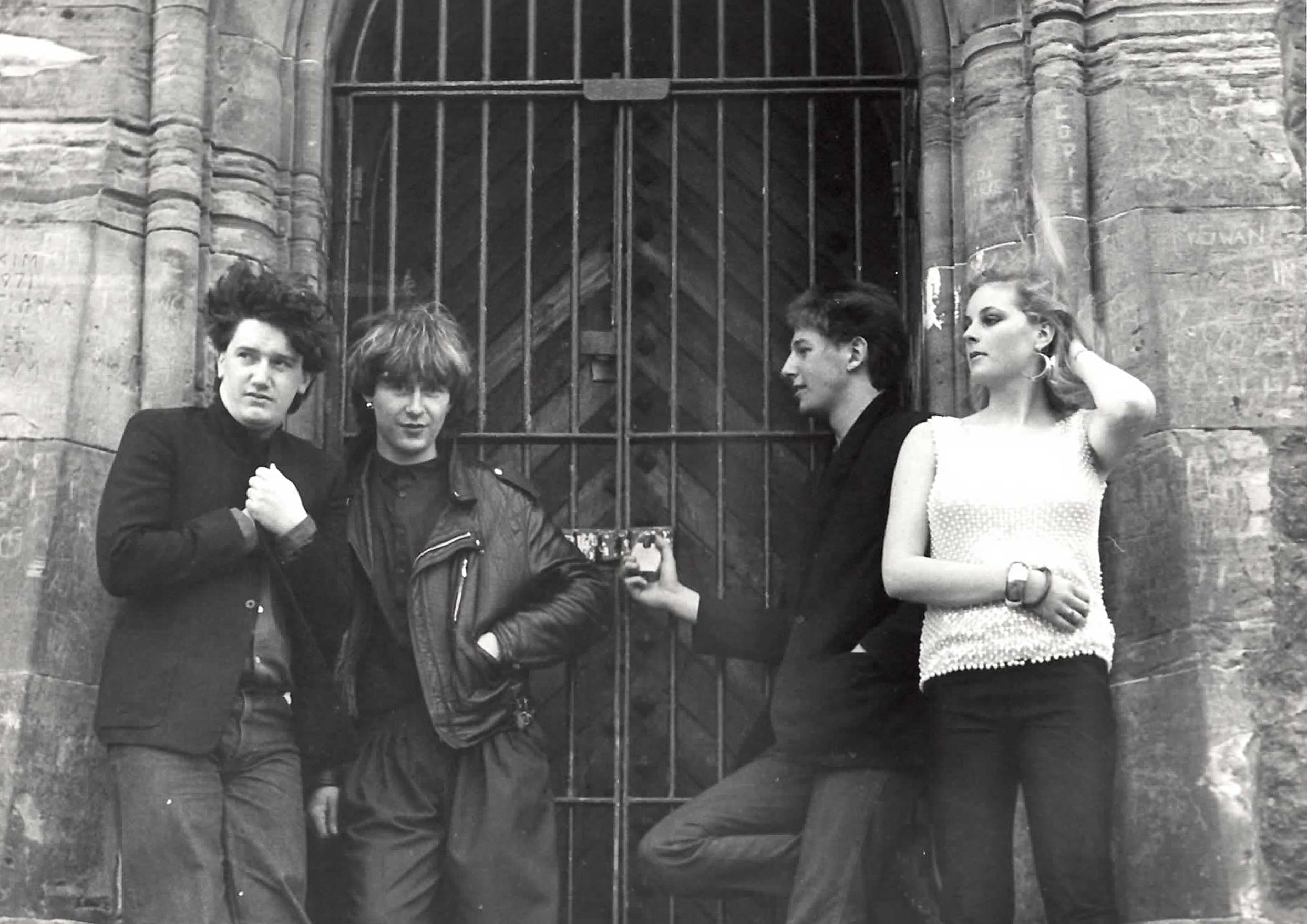

Dogmatic Element

In the end, it’s the sense of not just doing it yourself, but doing it for yourself that seems to unite the 11 disparate acts on Strange Passion.

“In a funny way, we were less interested in playing live than we were in just playing,” says Averill of SM Corp’s revolving cast of musicians. That’s probably why we didn’t play too many gigs. It was like a traditional session where we were just experimenting with what we were doing ourselves. We had no big ambitions to make records until a bit later on when we started to do shorter songs. Initially it was just about being there and doing it for ourselves.”

“Most people you meet now have an ambition to become something rather than purely making music for the sake of making it. People say it’s a bad thing to not have any ambition like that but really electronic music allowed you to do that. You could sit at home and program drum tracks and you could create something quite interesting without ever leaving your bedroom or living room. You were making it purely for yourself and hoping somebody would like it at the end of the day.”

The outsider art of people like Stano, Pete Hamilton of the Peridots and Barry Warner of Tripper Humane, Roger Doyle’s rampant experimentalism, the Virgin Prune’s confrontational theatrics, it all functioned to express personal freedoms, personal truths, disregarding or re-imagining the world they found themselves in.

Perhaps Eoin Freeney put it best. “You can only speak your truth because you know your truth and no one can take that away from you,” he says. “For me, the first lyrics I wrote were ‘If you want to believe go chant! Chant! Chant!/If you want to believe, then say so’. It was like me saying to myself, don’t mind what anyone else is saying, you say what you believe. Just be truthful to myself and don’t be what anyone else wants me to be. Honour myself and my integrity and be not afraid to express that in whatever creative form because that’s what I am.”

Strange Passion is out now on Cache Cache.