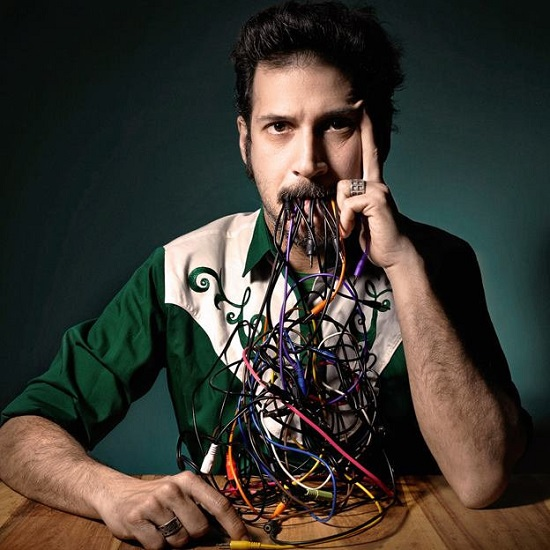

Photo: Rhodora Solis / Wikimedia Commons

Although privilege, individual ethics when it comes to following or flouting restrictions, dumb luck and random consequences of personal circumstance mean that the extent to which the coronavirus outbreak has impacted individuals varies wildly, it’s hard not to find anyone other than the ludicrously privileged who has not spent the last year feeling somewhat stranded.

On the one hand this collective hardship has had a unifying effect, yet the way these feelings of isolation manifest themselves within individual artists can vary wildly. Whether dealing with the after-effects of serious illness, being isolated from your home country or, or having a potentially career-defining tour snatched from you with a moment’s notice, everyone’s story is different.

With tours repeatedly postponed and the feasibility of future dates never quite assured, socially-distanced gigs rarely financially sustainable, emergency funding often failing to match the amounts applied for, a Conservative government actively hostile towards the arts and demandings their practitioners retrain, not to mention the draining effect that remaining in place can have on one’s creativity, there have been difficulties for those whose work is creative on top of the pandemic’s other horrors.

For this feature tQ spoke to just a few different artists who have been left, in one way or another, stranded since the outbreak of the pandemic over a year ago. They are industrial pioneers Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti, who have had to contend with shielding due to health issues as well as a nightmarish bout of long COVID; Greek-born, London-based musician Tasos Stamou trying to connect with his roots through unstable travel barriers; Newcastle metal band Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs, whose considerable momentum was all but wiped out once they cancelled a massive run of tour dates; and boundary-pushing noise artist Aja Ireland, who made her name via extraordinary sensorial live shows and has been forced to adapt to art without physical space. There are common threads between their various trials, hopes and fears, and there are differences too, but together they paint just a tiny part of the picture of a community left battered by a year like no other.

“Music, art and writing are a haven” – Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti

When the coronavirus pandemic broke out, Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti had to shield in their Norfolk home due to the latter’s pre-existing health conditions. “For a while it was a nightmare getting food and the basics during those months,” says Tutti, “but the village we live in were amazing. They’d set up a support group and are still on hand if we need them to help out.” Through healthy eating, gardening, exercise, podcasts, books and television they forged a new routine and found ways to cope. Then, however, Carter came down badly with COVID-19.

“To be honest I still have trouble fully remembering that time,” he says. “I was in such a state and on so much medication. For a while I was on a mega dose of steroids to help me breathe but they put me in such a weird, manic mental state I was unable to sleep properly. I remember one night sitting in the studio at two in the morning, wide awake and completely out of it, and I just started unplugging stuff and disconnecting the gear. I probably had some mad master plan to radically reorganise all the gear, but by the dawn I had almost completely stripped everything down. There was equipment laying all over the place. I’ve still no idea why I did it. We couldn’t use the studio for weeks after that.”

Tutti continues: “The first half of 2020 was wiped out due to us trying to avoid getting anything, then actually getting sick – that plus a few trips to A&E, hospital appointments and lots of medication. But now we’re both doing well thanks to the NHS who really came through for us. We’re still ultra-cautious, knowing first-hand just how horrendous the virus is.”

The disease continues to have an impact on Carter. “I’m still suffering from side effects, one of which is my voice breaking up,” he says. “For the first half of last year my post-covid issues definitely had an effect on what I could and couldn’t do.” Nevertheless, the pair have kept working. Fortunately they were winding down tours and public appearances anyway as the publicity cycles for Carter’s 2018 LP Chemistry Lessons Volume One and Tutti’s 2019 album TUTTI wound down. “Chris has been in the studio working non-stop and I’ve been the same writing my new book, and discussing the Art Sex Music film before it goes into production,” Tutti says.

“Being at home for such a long period of time has enabled us to get a lot of unfinished stuff done that had been hanging around,” she continues. “Once I get into the creative mindset the pandemic ‘disappears’, music, art and writing are a haven in that respect.”

“We have been used to working in one place for a long time now,” adds Carter. “You could say our house has always been one big hub of creativity, with different areas for different practices, we’re very fortunate in that respect. But being told you can’t go out does put you in a strange mindset, it’s an odd feeling not seeing or mixing with people, other than the occasional delivery driver at the end of the drive. And particularly because we’d been traveling and making appearances so often before. Having said that I don’t think we’ve ever been so productive.”

Interview by Patrick Clarke

“Livestreams don’t touch the sides of what my live performances are actually like.” – Aja Ireland

Photo by Noura Ikhlef

For many of us during the coronavirus pandemic, our senses were restricted to the limitations of four walls. Sights, sounds, and smells were all that of domestic mundanity. One of the biggest and most irksome restrictions was touch. A loss of physical contact is especially problematic for an artist like Aja, whose sensorial live performances of the past would be far from adherence to social distance guidelines. That sense of immersion that you get from the show by the Nottingham performance artist is near impossible to recreate virtually, she says herself: “I tried doing live streams, and I just didn’t get on with it. It doesn’t touch the sides of what my live performances are actually like!”

With physical live performance not an option, like many artists Aja used the lockdown as a time to relieve herself from pressure for self-care. “I think I already knew I needed a break,” she says. “I don’t think I would have taken a break if there wasn’t a lockdown. After touring so much, I was really burned out, I was tired and overwhelmed because I do everything myself. So actually, now I’m feeling excited to get back because I had a whole year off, I’ve never done that before. It’s always just been so intense, I think what Lockdown has taught me is the importance of really taking time off.”

As we wait with quiet optimism for June 21, when the UK Government plans to lift all restrictions on social contact, Aja is more than aware that things may not return to normal at that time. But the prospect of a new start for her is a chance to rejuvenate and reinvent while still sticking to her core reference points.

“It feels like I’m starting from scratch with a new look, but my inspiration is always going to be somewhat the same,” she explains. “It’s always going to be biology, nature, like slime, membranes. I always come back to the same inspirations, but myself and Lucy (LU LA LOOP) are going to be creating a new costume. And I think really, what I’d like to do for the next kind of bout of performances is cohesion. I’d like all the elements to bleed into each other. There’s not been any definitive look for my tours and like to stick to a few new ones for the next tour.“

She won’t be jumping the gun to perform. Especially with all the uncertainty. “I think for me, I’m probably going to wait until things are actually better and relatively back to normal. I feel like if I plan things and then everything changes, I won’t be able to deal with that mentally. So in my head, now, what I’m doing at the moment is planning the new costume, getting ready to get back and of course releasing my new record on Opal Tapes.”

Interview by Aimee Armstrong

“It’s a lot of people whose mental health hinges on live music” – Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs

Before the pandemic, Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs were riding a considerable wave of momentum. Their brand of colossally heavy psychedelic noise rock was proving a hit beyond any scope they might have imagined. Off the back of an exalted live reputation, the group were selling out bigger and bigger shows like a 1,000 capacity gig at London’s Scala. For their third album Viscerals, they had their first run of dates booked across the US across March and April. “Going to America felt like the next step, something we hadn’t done before,” says guitarist Adam Sykes over the phone.

As the severity of the pandemic became more and more apparent, so too did the reality that the group’s American dates wouldn’t be able to take place. The sudden erasure of live income for a band of Pigs’ stature – a group rarely away from the road – is significant. “A lot of the costs for America, visas and such, we already paid for and became useless essentially,” Sykes says. “We’ve taken a hit as a unit.” Regardless, he says “we consider ourselves the lucky ones in all of this. The majority of Pigs work full time along with the band, so we’re not in the position where our income has been entirely halted.” Their fanbase is now significant enough that they found plenty of support when it came to a long-demanded repress of their first record, ‘The Wizard And The Seven Swines’.

In an interview with tQ last year, the Pigs spoke much about how their intense performances act as a coping mechanism; “I feel like we live in a really noisy world, and […] playing really noisy music feels like it cancels the noise out,” said frontman Matt Baty. The most severe effect of gigs’ sudden, indefinite cancellation was therefore mental.

“It’s a lot of people whose mental health hinges on live music.” Sykes explains. “Playing gigs had become a crutch, as regards our mental health and our happiness. I’ve had very little motivation this past year. I guess a lot of artists may feel pressure.” Though the rest of the Pigs were able to get the occasional rehearsal in during the summer’s lull in restrictions, due to health issues Sykes has been shielding for the entirety of the last year. “I think that’s probably the hardest aspect of it, the thing I miss the most, not being able to play shows. Especially the shows that we had booked in and we were looking forward to for quite some time.”

Throughout our conversation, Sykes is keen to stress that he considers the band fairly fortunate – they’d built up enough of a fanbase that they hope their old momentum won’t be too hard to pick back up once things resume – they have a few cautiously-booked summer festival shows, a UK tour in November and US shows next year. “It’s hard to say how [the music industry] will move forward, what will remain in place and what won’t, but hopefully we’re over that first bump in our careers,” he continues. “But I worry about the people who were only just getting a bit of momentum going. If this was two years prior, I dread to think of the implications it would have had for us.

Interview by Patrick Clarke

“Many creative individuals have already abandoned this boat” – Tasos Stamou

Though Tasos Stamou is a long-term UK resident, one who plays an important part in the less po-faced wings of the isle’s improv and sound art scenes, his heritage informs a lot of his music. Latest release Greek Drama, on veteran freakazoid label Chocolate Monk, leans on the theme especially heavily, being a fuggy mixup of covers, samples and interpolations from the Hellenic folk canon. It was even recorded back in the old country last summer – “visiting my father’s land in between lockdowns,” say the sleevenotes.

Those lockdowns have made for, says Stamou, “an extremely painful year musically, especially since I was supposed to have a really busy performance schedule. I seriously miss performing and improvising with other musicians.” There were limited blessings nevertheless. “I made a lot of new instruments, and there were some musicians buying them for lockdown recordings.” A series of circuit bending workshops held over Zoom also went in the positive column.

The musician has taken lockdown fever further than most, too, creating a pandemic-crazed alter ego named Armageddon. As demonstrated on debut EP Dance Till The End Of Time, this is a vehicle for blunt dystopian proclamations and clanking home-fried electro. “Armageddon was created during the tougher, most stressful part of the first lockdown while worrying too much about where humanity is heading. He is a Frankenstein monster created in COVID times, but he accumulates years of sociopolitical frustration and the need for musical activism.”

Meanwhile, the real-life Stamou is concluding his decade of London living and moving to Essex – pretty much as this article is published, in fact. “I was planning an escape for three years or more. I have been gradually experiencing less fun, less creative stimulation and less communication. And, to be honest, a less profitable and more expensive everyday life. “Many creative individuals have already abandoned this boat. In the new reality superimposed by the pandemic, it will become even more dystopian, in the cultural sense. I might be wrong but I am not in the mood to find out by staying here.”

This is all afforded an extra, sharper angle by Stamou’s status as an immigrant in the UK during the most nihilistic period of petty nationalism in its modern history. “During the last six years I started being culturally homesick. It might sound a bit of a cliché, but I realised I feel more Greek as an immigrant than when I lived there. The reason I musically investigated my Greek roots is due to the – in contrast to the general belief – multi-ethnic history of Greece. In a way I feel more European than ever, but in a Europe which only exists in a fairytale at the moment. If liberal ideas and progressive developments become extinct, there are no more interesting things I can see behind that.

“My ideal humanity lives in this globe in peace and prosperity. My view of the current state is exactly the opposite. I am not totally pessimistic though. I believe people have one last chance to re-establish whatever is there to be saved from an economic, social, political, cultural and psychological forthcoming crisis, which at the moment is being taken in advantage of the capital’s interests.”

Interview by Noel Gardner