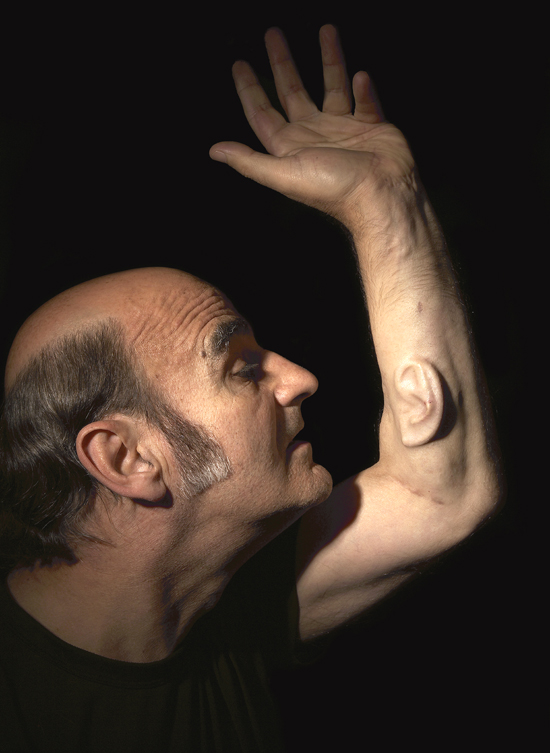

In the foreword to the MIT Press published Stelarc: The Monograph, William Gibson recalls his first meeting with the world renowned performance artist who deals with the intersections of human body and technology. When I walked with Stelarc towards one of those those identikit, franchised coffee shops, I too also “found that he radiated a most remarkable calm and amiability, as though the extraordinary adventures he’d put ‘the body’ through had somehow freed him from the ordinary levels of anxiety that most of us experience.” A six year old kid we bumped into on the way for our drink helped me to get used to the extra ear that the Cyprus born, Australian artist has grown on his arm, as a part of his ongoing Engineering Internet Organ project. The boy simply and bluntly asked Stelarc, "Why is it here? … Can I touch it?" He simply got accustomed to the fact that some people have their body parts in different places than the others. “The human body is obsolete” is what he announced at the outset of his career as an artist years ago but the look of the human body – as the staring eyes of all our passers-by could confirm – is much more obsolete than the meat itself. Over a period of 45 years he has conducted performances including 26 suspensions with hooks through his flesh, he has allowed his body to be controlled by electronic muscle stimulators controlled by third parties and he has performed with a robotic third arm, as well as growing the aforementioned ear on his body.

In the same foreword Gibson also notes that he “experience(s) [Stelarc’s art] in the context that includes circuses, freak shows, medical museums, the passions of solitary inventors”. He doesn’t see it as futuristic, but as the “moments of the purest technologically induced cognitive disjunction”. This is a really interesting and (possibly) accurate view of the work of an artist who is usually introduced as the only person in the world of fine art who is not dealing with the past and the present. But what is appropriate when it comes to watching and thinking is not always the best way to talk about it. In the world of easy access to the data, it’s sometimes more interesting to chat about the future. It can reveal a bit more about contemporaneity. Especially if you’re looking through the prism of art, film and literature.

Do you believe in the existence of soul, ghosts or any other metaphysical presences that can enter our bodies?

Stelarc: I guess the more and more performances I’ve done, the more and more I think that I have no mind of my own, nor any mind at all in the traditional metaphysical sense. When you look at this body [points at self] this physical, phenomenological, operating, interacting body, this body is totally obsolete and empty, there is nothing inside my head. What’s important is not what is inside you or me, but what is happening between people in the medium of language that we use to communicate, in the social institutions within which we operate and in the culture that we’ve been conditioned to inhabit. So it’s a Western, metaphysical assumption to imagine that there is something inside our bodies. With Plato it was a homunculus, the beginning – in Christian theology – of a soul inside our body, with Descartes the mind was a different substance from the brain; Freud distinguished id, ego and superego as a way of explaining the internal motivations and repressed behaviours of the body. I feel that it’s unnecessary to construct anything that’s internal. It’s the interaction in personal and social spaces that constructs what it means to be human. So we’re human because of our social systems, our technologies and our culture. We’re human precisely because we have neither a mind nor a soul.

Talking about the body we can use the Platonic significance of a body being a prison for the soul, we can talk about Foucaultian means of controlling the body. You are using Your body as a kind of canvas, a place of experimentation.

S: It’s difficult with language because as soon as you say my body, it means that there is someone who is me and there is something that is my body. Language perpetuates the Cartesian Theatre. The best way to say this is that this body becomes its own means of expression, experimentation and experience. It’s a kind of convenient material to experiment with itself. Some of the projects and performances would have a completely different meaning and different ethical and sociological implications, if they were done to a different body. For example if I put a sculpture inside your body, this would have different ethical consequences. If I harm your body or if I do this action without your permission there is a problem, not to mention the real possibility of harm. So to do a performance with this body means that You don’t have these kinds of problems of personal or gender interventions. These problems never eventuate. That is they are effectively erased as issues.

The so-called cyberpunk movement distinguished two main ways of the human evolution. While the first one is connected to the technology incorporated into our bodies (cyborgisations, etc.), the other one is talking about the ghost in the network. Do You think those kinds of predictions are accurate?

S: I think what’s interesting about these projects and performances, is that they generate contestable futures, they speculate on a multiplicity of different bodily constructs, of alternate cyborg constructs. Instead of a cyborg resulting from some kind of medical/military idea of a traumatised body, a body whose organs have been replaced by technology, we can simply think of amplifying or extending the body with its internet connectivity. This constructs a task envelope where the body performs beyond the boundaries of its skin and beyond the local space that it inhabits.

Of course there are utopian and dystopian problems with this. It begins to sound like eugenics. It becomes politically and philosophically problematic when body modifications are imposed. Certainly we live in the age of body hacking, gene mapping, prosthetic augmentations and organ printing and we’re constructing these liminal spaces of transition. What the body is and how the body operates becomes completely problematic and in fact the body becomes a kind of floating signifier. The body means whatever meaning we give it: the virtual body, the machine body, the biological body. In fact I think that it will always be a combination of – in the cyberpunk terms – meat, metal and code. But the iterations will be different, unexpected, surprising and perhaps shocking. For example it could be a body with an additional third hand, so it means you see the biological body with mechanical attachments, that amplify or extend its capabilities. But that’s just one possibility. Another possibility is that with the increasing micro-miniaturisation of machines which now become nano-scale, your body may look the same in appearance but inside it will be inhabited, it will be re-colonised by the micro-miniaturised machines to augment the bacterial population for example. So it’s just another one of the contestable futures.

As well as Circulating Flesh, we now have the possibility of Fractal Flesh and Phantom Flesh. Viral code, manifested as images in the internet becoming these autonomous, intelligent, interactive entities. So the realm of posthuman may not depend on the body, may not depend on machines, but rather the posthuman becomes Phantom Flesh. That’s a possibility. Of course you can always think like Ray Kurzweil and postulate the idea of a Singularity. You can look at technology, see it’s exponential growth and speculate that in 2050 suddenly the machines will take over. But I don’t think it will happen like this. In fact I think there will be a multiplication and diversification of possibilities which result in a blurring of the body and its machines, of brain intelligence and artificial intelligence. It’s likely that technology and the human body will integrate, will iterate into different forms with unexpected functions. The future should be one of contingency, not of necessity. It’s not interesting to have the kind of dystopian future where one kind of artificial life form erases, eradicates or annihilates the previous. I don’t think it will be so simple.

So, what do You think about the concept of artificial intelligence? When it comes to the subject of AI many people seem to be talking about a kind of mystic, spiritual element which will occur during the process of constructing the self aware machine. Paradoxically the platonic dualism and the existence of the soul appear between their words.

S: What we have to remember is to be an intelligent agent – whatever kind of agent you are: the virtual agent, the human agent, an animal agent – You have to be both embodied in some physical way, and also embedded in the world. So it means that that the agent whether it’s an artificial agent or not has to have a kind of physical embodiment to be able to interact, operate, manipulate and navigate in this complex world. It doesn’t make sense to have an intelligent agent somehow disembodied and disconnected from its environment. The robot body doesn’t have to look human but it does need some kind of architecture to sense the world, to process that information and to act upon the world. Whether you are biological body, an animal body, an insect body, a machine body or just a computer internet system, there has to be a way of interfacing and interacting.

Therefore in the 60s when people were enthusiastically researching artificial intelligence, they were talking about it in an abstract way. That somehow you can construct a mind with only software and somehow this algorithmic mind will become sufficient in-itself. But people found out that it was a bad paradigm because – really – instead of talking about artificial intelligence, it’s more meaningful to talk about artificial life. This artificial intelligence has to be embodied in some way and it has to interact with it’s environment in other ways for it to enable it to perform intelligent behaviours. So the artificial intelligence really became replaced by experimenting with artificial life. Instead of making an abstract program that runs on the computer, why not make a little robot, put it in the real world, give it some simple sensing possibilities, and than see what happens. What happens is that there is a possibility of emergent behaviour, expectedly this little robot with very simple senses begins to generate some interesting behaviour such as avoidance behaviour, perhaps flocking behaviour, perhaps predator and prey behaviour. That’s what we have to remember, that the body might be a very different body, but it should be some kind of a body. Whether it’s a biological body, a cyborg body or a robot. The behaviour of living things is interesting because it expresses the complexity of the world it inhabits.

You’ve already said that You don’t believe in the Ray Kurzweil / The Terminator like vision of the future, but what will happen if this kind of artificial agent generates predator and prey behaviour?

S: I think this kind of prediction is very simplistic and highly speculative. It’s a projection of our Frankenstein fears and Faustian anxieties. Of course there is a possibility that robots will develop agency and therefore autonomy and maybe they will also develop the antagonism to human bodies, but it’s just another kind of sci-fi scenario. It doesn’t have to happen that way. I think these kinds of hypothesis are an indictment about what it means to be human, than being an objective analysis of the future.

So, do you see any ethical boundaries on technical or medical experimentation?

S: I think that’s a reasonable concern, but I also think that we have to realise or imagine that all these systems whether they are ethical, technological or biological, these are dynamic systems. They aren’t static, they are quite unstable. They are changing depending on shifting the ratio of possibilities that are generated by new inventions and new social systems. For example with every new technology, there is a new kind of instrument. There is unexpected and alternate information and images generated, and this creates an unstable moment rather than one that is simplistically enabling. People imagine that with every new technology in the our consumer society, we will better enable the body. We will be able to do things faster, more precisely. But with every new technology there’s a new kind of accident – as Paul Virillio points out. There are unexpected situations that will arise. So this exposes the unstable situation that technology contributes to.

Yes, we have to evaluate whether it’s good or bad or if it is politically correct or not, whether the genetically modified plants will be a problem in our natural environment and whether the nano-robots will cause unexpected catastrophes and new kinds of problems that bacteria and viruses caused before in our bodies. Yes, we have to consider all these factors, but in a dynamic way, re-evaluating the situation as we go along. For example when we first fertilised an egg in-vitro, at first the Catholic church was happy about this, because women with blocked Fallopian tubes could now have children. For the Catholic church there was no ethical problem with enabling women to have children. The problem is that we did not foresee that if we can fertilise eggs outside the womb then we don’t have to reinsert it in the same body. And when this process produces an excess of unwanted fertilized eggs, we can freeze them, we can do research on them or we can flush them down the toilet. I’m sure the Catholic church wouldn’t be happy about this, but these are those unexpected problems that occur. But you can’t be short-sighted, you can’t stop the world because of some past religious or ethical discourse, that belongs to a previous history. We can’t arbitrarily say, ‘Oh, now we have to stop.’ What we have to do though is to better manage and evaluate, discuss those possibilities and decide do we want to appropriate them, do we want to discard them or do we want to come up with alternate possibilities.

Do you think that the evolution of technology will deepen the divides in society more than ever before? Technology is always expensive…

S: Well, it’s a compelling argument that technology merely amplifies our social differences of equality and access, but also a problematic one. Our capitalist and consumer society depends on generating needs and desires that are often arbitrary and about accelerating our economic engines.

Historically there has never been an equality of opportunity or access. This depends on geography, religious imperatives, social and political systems and individual wealth. Being privileged to have first use of new technologies is not necessarily beneficial. The first person who had a heart transplant was privileged because of his social status, white middle class access to western medical technology, but he didn’t live very much longer. He was though an experiment that now results in countless others having successful heart transplants with increased longevity. So one can argue that it might be better that you are not first person to access new technologies.

All the time that we’re talking You seem to be quite optimistic about the evolution of technology. Survival Research Laboratories seem to have a different point of view.

S: Mark Pauline and SRL are seemingly dystopian with their dangerous crash and explosive machine performances. [laughs] We’re good friends actually. I’m impressed by their machines and robots. Mark Pauline had an accident with an explosion in which his hand got badly mangled. Even with surgery his hand is still a disconcerting lump with an opposable toe for a thumb. Anyway, as I said what’s interesting about the arts is that they generate a multiplicity of contestable futures, the multiplicity of the future scenarios. It’s about challenging the status quo.

Alternate uses of new technologies, unexpected outcomes… Look at the internet which was originally a military/university system of communication and now it has become widely accessible becoming itself a medium of artistic expression. Similarly with Virtual Reality. Its military uses have been overtaken by more meaningful explorations with visualizing data, modelling architectural spaces and creating new possibilities with Augmented Reality, especially applicable in difficult and even remote robot surgery. So how can we generate unexpected possibilities with new technologies and produce something that initiates a new kind of questioning. Most scientific research is reductive and often involved in finding solutions, it has specific aims and hopes for particular outcome. Art is an alternate practice. It wants to ask questions rather than find particular answers. It wants to generate a multiplicity of possibilities. Survival Research Labs certainly multiply anxieties and concerns rather than simplistically affirming particular values.

Do you make a distinction between pop culture and culture with a capital “C”? Do You read sci-fi novels or watch genre movies?

S: You can’t escape your social situation. In a Heideggerian sense we’re thrown into a particular moment in history, into a particular culture of technology and discourse. David Cronenberg’s Videodrome is one of my favourite movies and while I was living in Japan, the director of Tetsuo gave my a copy of the original film. Of course I know William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s work quite well. They’re both good friends of mine. But I have to say I don’t read much science-fiction these days. I certainly did that as a high school student but since then – and I guess because of my artistic practice – I’m more interested in reading about the cognitive sciences, articles in Scientific American or books about physics and consciousness Studies. Because in a sense my projects and performances generate ideas that I want to elaborate on and make associations with other ideas and it’s really interesting to find out that some of the ideas that come from these performances are ideas that certain cognitive scientists are in sync with. Or if there are disagreements I want to examine those alternate ideas. What is meaningful is establishing connections and counterpoints to these articulated experiences.

However from these performances and projects many writers and directors draw their inspiration…

S: You know, it’s always difficult to pin point particular influences. What sometimes happens with the artist though is that theorists or sometimes science-fiction writers will appropriate a particular idea but won’t credit the artist. If I was an author of a book, then people would be obliged to cite the artist in an appropriate and professional way. In the realm of text and theory, authors cite other authors but don’t often credit an artist. Sometimes I’ve been asked whether I have been influenced by a particular film, for example where a body was suspended (The Cell, 2000). But then when you look at when the film was made and when my first body suspension occurred it’s quite obvious there wasn’t an influence. In fact I’ve never been to India or Malaysia and seen any Hindu rituals of piercing. It was flicking through a book that I first came across images of these rituals. Having done a series of suspension performances with harnesses and ropes, it became apparent that the body was more supported than suspended. So suspending your body with insertions into the skin was certainly the more elegant solution. The stretched skin becomes a gravitational landscape – what it means to be suspended in a 1G gravitational field.

It’s the same with the three films of the inside of my body which I made before the first suspension event, between 1973-1975, five years before the Third Hand project was completed. So I was exploring the inside of the human body before anything else. The Stomach Sculpture which was done in 1993 wasn’t the first body probe I did. People also think that my interest in Second Life, in the virtual has been for only these past three or four years. But in the mid 1980s I was performing with the Virtual Body (with real-time motion capture) and in 1991 I was performing with the Virtual Arm (with a gesture recognition command language, actuated by data gloves). So my interest in the the virtual goes back many years. What’s interesting about Second Life is that it is a virtual online interactive space, populated by other avatars. With me there was always a kind of oscillation between physically exploring the bodily parameters on one hand, and augmenting the body on the other. This idea of meat, metal and code has been explored between these possibilities for the last 45 years. It’s not a linear development from the physically difficult to technically complex or from the actual to the virtual.

These concerns have existed simultaneously. They interact in a kind of rhizomatic way. It’s not that they develop in a linear progressive way. The internet is more rhizomatic than hierarchical. Now it grows much more organically. With every new laptop, in every different location, with bits of viral software, with different hacking possibilities… So what’s happening is not directed but develops in surprising and complex ways.

There’s no Big Brother…

S: Massive centralization, we can argue has never really eventuated. That’s the thing. In our science-fiction we imagined that the problem with computers will be caused by the centralised control of everybody. OK, Foucault’s analysis was very important, but nowadays the idea of panopticon is much more complex because it infects us globally. We have embedded web cams in a multiplicity of dispersed locations. When you go to the UK, there are cameras everywhere, but I’m not worried about this. In fact I think we need more surveillance – and we need internal surveillance of the human body. The human body does not have an appropriate, adequate internal surveillance system. The things that happen now to our bodies on cellular level might be the beginnings of a tumour, it might be the beginnings of some other pathological changes in chemistry or temperature, that will result in the damage, demise or even death of the human body. We have no internal, early warning system to become aware of this until the symptoms surface, until you can feel a lump in your breast, and then it’s too late. But if we could detect it through this internal bodily surveillance, through nano-sensors and nano-machines at the cellular level, then this would enable us to better manage our pathologies, our physiology. And also it might create the possibility of designing or redesigning the human body inside-out, atoms up. A kind of inverse embodiment. I think it would be a better strategy than trying to redesign the body externally. Certainly prosthetic augmentation alters the form and functions of the body, but the human body is very complex. But if you are able to make small changes, atom by atom, inside-out, then there is a possibility of re-engineering a new body that could by managed incrementally.

As You said, Videodrome is one of Your favourite movies. Cronenberg’s vision concerns a radical change, the new world build upon the ruins of the old one, “Long live the new flesh.” Your vision is more evolutionary than revolutionary though.

S: We’re living in an interesting times now. We can preserve a dead body forever, using plastination. Simultaneously we can sustain a comatose body indefinitely on a technological life support system. So the cadavers and comatose bodies can exist now simultaneously. Dead bodies need not decompose. Near dead bodies need not die. Whilst at the same time we have cryogenically preserved bodies that await reanimation in some imagined future. We are also now creating partially living entities in vitro, in the lab. These chimeras can be hybrids of plant, animal and even human genes. So what it means to be a body becomes totally problematic as more liminal spaces proliferate. What it means to be dead now, is almost as meaningful a question to ask as what it means to be alive. Dead people can be reanimated. You can die and might be revived on the surgical table. Or if you have a heart attack and if I know the resuscitation procedure I might be lucky enough to kick start your heart again. When you have a surgery your basic life functions are suspended either by freezing your body, by re-circulating your blood (or using a synthetic substitute) and by having you connected to an artificial lung. Now most of us will not die a biological death. We will either die because of some machine disaster or when we have our life-support system switched off. We have to re-evaluate what it means to be alive but also equally what it means to die. It’s doubly disconcerting when the State not only conditions, coerces and constrains your life but also disputes how you choose to die.

That’s interesting because science-fiction always wondered what is life, not what is death. Where is the line when the robot or a program become alive…

S: My performance in Wroclaw, at the Biennale Wro 2011 examined the idea of what constitutes aliveness. If the avatar is activated and animated, if it has facial expressions, we generate a kind of aliveness and a kind of “e-motion”. It might not yet be an intelligent and complex interactivity, but it’s the beginning of that. If we imbue the avatar with code that enables its behaviour to evolve for the duration of the performance, then perhaps this becomes a more autonomous and perhaps intelligent agent. If we can provide a vision system, it can do sound location, if we can have some kind of force feedback operating between the avatar and the physical body that is interacting with it, with some haptic technology, then there’s a possibility that this virtual entity will be able to perform more subtle, more unpredictable and more meaningful actions in the 3D space that it operates in. Its task envelope becomes and extended operational system. This is what this performance – in a very basic sense – was exploring. That this physical body, through its movements, through it’s arm gestures, is able to activate and animate an avatar to generate a sense of aliveness and of “e-emotion”. It was not a performance about anything. It was a performance with something else.

Have You seen those two popular movies about avatars? James Cameron’s Avatar and Jonathan Mostow’s Surrogates?

S: I think those two ideas expressed in the movies are becoming possible already. They extrapolate the possibility that not only can you access and actuate a virtual avatar, like in Second Life, but have a surrogate physical body that your “mind” can take over. A somewhat problematic philosophical situation. Actually what would be more interesting would be not having a Second Life but rather a Third Life so that an intelligent and autonomous avatar could access a physical body and perform with it in the real world. When I was in Wrocław 15 years ago I did a performance with the Third Hand and it was one of the last performances with it. This split body performance was a body installation where I was controlling my third hand with EMG signals from my abdominal and leg muscles whilst simultaneously the left side of my body was being controlled by the people who came to the performance. Through the touch screen interface they were able to program the movements of my body and then the computer interfaces muscle stimulation system delivered 15-50 volts to the leg and arm muscles and my body moved involuntarily, moved to their choreography.

The earlier project of similar conceptual concerns was Fractal Flesh in 1995 when people in other places were accessing my body and also remotely making it move. OK, the system wasn’t so sophisticated and at the time it cost me about $5,000 to make it, but if this system was a two way system… If a half of my body could move a half of your body and the other half of your body would be able to prompt the other half of my body, we would be in control of a half of each others bodies, which would mean our agency would be distributed between two bodies and we would be spatially separated but electronically connected. I think this is a really interesting idea, not so much a problem of control, but an experience of split bodies and multiple agencies. People, when they talk about Fractal Flesh they ask who is in control. They think about the possibility that your body could be hacked by someone else. But it’s not really what was postulated. What was postulated and speculated is the possibility of distributed agency, manifested in the multiplicity of bodies spatially separated but electronically connected and this is what is alluded to in Fractal Flesh. An intimacy without proximity. An intimacy without skin contact.

During your performances people are also somehow connected. They react quite physically because they experience Your injured body, Your pain. The link between You and the audience is not electronic, it’s emotional. How predictable are the reactions? Do You expect a specific response?

There’s always a spectrum of response. But to be honest for this artist it’s not about audience reactions. The performances are not structured for a audience. Many of my performances were done with no people in attendance, a lot of actions had no one watching them. I don’t do a performance for an audience as such. If I want to make the audience excited or interested, I’m not stupid, I can think of different emotive and aesthetic strategies that will attract their attention and seduce their senses. In other words, there are no pyrotechnics with these performances. A Third Hand performance would begin when the body was switched on and would end when a body was switched off. A suspension would begin when the body was winched up and end when it touched down. Sometimes a performance would not have a beginning or end as such. People assisting would be there attaching electrodes and wiring up the body. They would be there after the action to disconnect me. The Ear On Arm project is initiated with an idea in 1996, it takes 10 years for the first surgical procedures to take place. The stem cell work is still not done. It may take another three to five years to arrive at the point when performance can take place. Hopefully the conceptual raison d’être is interesting enough that people might not perhaps appreciate what they see immediately but they will go away bemused or perplexed and hopefully there are questions that they begin to ask themselves and others. It’s not a matter of the success or failure of a performance, it’s a matter of experimenting, exploring and interfacing.

Of course I’m pleased if someone says “I found this performance interesting” or “this performance affected me emotionally”. Of course you’re pleased to hear this because there’s a connection that’s made which is instant, which is unconditional. But I think some of these actions don’t require an instant response. Sometimes it does take some time for an action to be considered. The trace of the performance might be more profound than the act itself. For example with this performance in Wrocław in 2011, what people saw was my body making gestures and moving, they see an avatar choreography. The performance started before people arrived, and than it suddenly finished with no explanation. On the projected screen, the Second Life window was closed, revealing the smaller window of the Kinect system with the skeletal mapping visible, then that was clicked off and it revealed the window with a code for the interface between the two systems and then this was clicked off, the computer was switched off and the performance was kind of over. There was no narrative, there was no story. It was activating and animating an avatar for a certain duration. Generating collisions with virtual objects that composed the sounds. In other words the physical and virtual choreography composed the acoustical landscape that immersed the audience. In another project – Exoskeleton – the six legged walking robot that the artist is on, the artist simply takes the robot for a walk. Perhaps some people accepted it as an experience in itself. Some people understood, some didn’t, some walked away expecting more. But hopefully others were still irritated or inquisitive much later on. [laughs]

You also give public lectures. Do you want to explain your performative actions?

S: Oh, when I do a presentation it’s not about explanation or justification of these projects and performances. And the projects and performances are not about illustrating some discourse or theoretical narrative. What you say is not about what you do – except in the most simple sense. There’s a relationship between the two but it is problematic and unstable. Certainly there is an interest in ideas, but ones that have been generated by actions. In my case my ideas are authenticated by my actions. In turn, there is an acceptance that I have to take the physical consequences for these ideas. It’s not just about an academic interest. But the performances do question some personal and philosophical assumptions we make about the body and how it operates and becomes aware in the world. And thus the interest in our evolutionary architecture, the interest in cognitive sciences and the history of ideas examined by philosophers. If art is about information, then a textual or verbal documentation is sufficient. But I’m always uneasy when there’s an assertion that art can be explained. Art is not about information but about affect. It doesn’t require information so much as it demands an experience. What artists do is generate contestable futures, ones that can be examined, evaluated, possibly appropriated, most often disregarded. In a certain way they can be represented by text, but again not as an explanation or a justification. I’m even uneasy about speaking as a reflection on what has happened. That’s an act in itself and shouldn’t be confused with the artwork. That’s not to belittle a theorist, a science fiction writer or a philosopher. Their words are performative acts in themselves. That’s what’s meaningful about what they do. That’s the distinction that needs to be made. This artist is not in the business of explanation, education or illustration. Art can be messy and it can be pornographic. Sometimes shocking and even dangerous. It certainly should be unsettling, uncertain and ambivalent. If it doesn’t surprise it’s probably not interesting art.