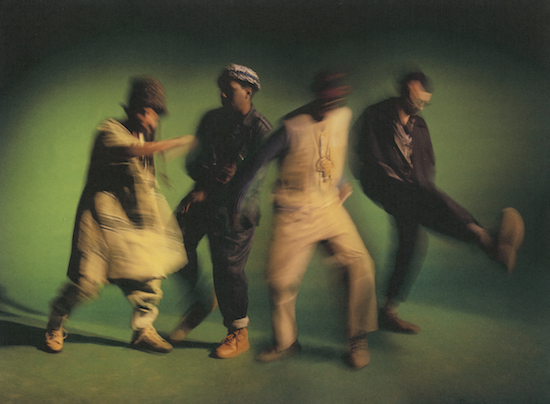

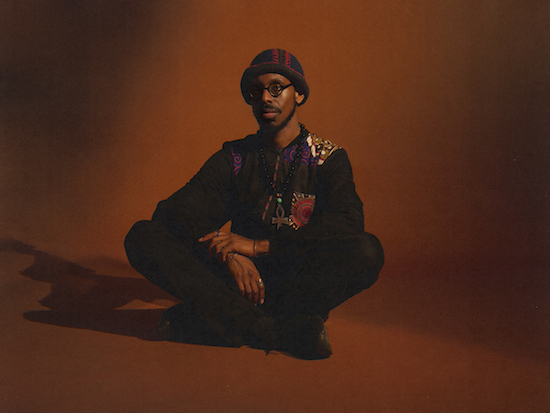

All band portraits by Udoma Janssen

In The Last Angel Of History, John Akomfrah’s experimental documentary released in 1996, the narrator is a “badboy scavenger poet-figure” known as the Data Thief. Roaming through history, the Data Thief gathers “techno fossils”, fragments of culture from different epochs, with which he hopes to be able to decode the future. One of the central arguments of the film – which became a vital document of the Afrofuturist aesthetic – is that sampling technology, which allowed for the creation of electronic music forms such as techno and jungle, was able to break down time. Through sampling, producers were able to access all previous eras of music simultaneously and create music that sounded like it was from the future, because it had no relation no anything that existed in the present.

Black To The Future, the fourth album from visionary quartet Sons Of Kemet, who have long been key innovators in London’s dynamic and ever-evolving jazz scene, is based on a similar premise. An essay to accompany the album, written by saxophonist-philosopher Shabaka Hutchings states: “Music can be likened to a time travelling vessel whereby cultural value systems of the past are encoded within sound and projected/ protected throughout ages.” Though Sons Of Kemet’s music uses analogue instruments rather than electronic ones, the idea that music contains encoded information is central to the album. “I’ve been very influenced by that”, Hutchings says of The Last Angel Of History. “I like that idea that it’s not just what’s on the surface. You’ve got to consider these things and look deeper into them for what they give us, on an intuitive level, not just a literal level”.

Black To The Future is a noticeable expansion from the band’s previous work. While the compulsive rhythms, energetic sax melodies and deep tuba lines are all still present, the album is bolstered by a stellar range of guest musicians including Kojey Radical, Moor Mother, Lianne La Havas and D Double E. It is also a document of a particular moment in history. Coming out less than a month after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin was convicted for the murder of George Floyd, the event which sparked the Black Lives Matter protests last year, the album is indelibly marked by considerations of racial injustice. However, it would be limiting to label the record a ‘political album’ in the conventional sense of the word. Instead, the record expands the parameters of what power could mean, while exploring the nature of time, ancestral knowledge and African-derived cosmologies.

When I first arrive at the band’s studio and rehearsal space, Total Refreshment Centre in Stoke Newington, only Hutchings and Tom Skinner, one of the band’s two drummers, are there to meet me, though the other drummer, Eddie Wakili-Hick later joins us. Perhaps because time is limited (somewhat ironically, given the subject matter), we dive straight into the philosophical underpinnings of the album. Whereas the tracks on the band’s last LP, 2018’s Your Queen is a Reptile, were each named in honour of a

prominent female figure from the African diaspora, the tracks on Black To The Future instead spell out a poem which reads:

Field negus / Pick up your burning cross / Think of home / Hustle / For the culture / To never forget the source / In remembrance of those fallen / Let the circle be unbroken / Envision yourself levitating / Throughout the madness, stay strong / Black.

“The poem is just a reflection of all the stuff that I was reading and thinking about at that time, especially to do with issues of Blackness and what it means to go into the future”, Hutchings says. “You can think of music as being a thing in itself that is just sonic, but I don’t think it is. Music is part of a bigger scheme of what your world view is, and what your temperament is at any given time.”

While Hutchings developed the initial kernel of the idea that would shape the album, it was up to the other members of the band to interpret it. “It’s been the way that we’ve worked for some time, even on the previous albums”, says Tom Skinner. “Shabaka presented music to us in its rawest form – the bare bones of the ideas – which we’ve then had to interpret in our own way, informed by where we’re at.” During the recording process, the main emphasis before each session was to find a way for the band members to share in a collective headspace. “Shabaka really got into the Wim Hof breathing technique. He showed it to us and sometimes we’d do it collectively or we’d go off and do it by ourselves”, Skinner continues. “It was a way of bringing us together, allowing the music to come from within without any restriction.”

The recording process was also shaped by a strict limit on the number of takes. As Hutchings explains: “None of the tracks were recorded with more than two takes. What we did is we recorded the drums, we played for ten, 15 minutes, before the tuba came in. I might play the melody many times. The idea is that kind of communality, where you want to get out of the individual anxiety of what specifically you’re playing, so it can just become a group enterprise, and it can only become a group enterprise after we’ve been playing circularly for ages.”

The concept of circularity, and circling back to something that Hutchings refers to as “the Source”, is another key conceptual framework for the album. The track ‘To Never Forget The Source’, sits in the exact midpoint of the album, a centre point that be accessed from both the past and from the future. In his essay, Hutchings write: “The Source refers to the principles which govern traditional African cosmologies/ ontological outlooks and symbolises the inner journey.”

This theme, of returning to a place of ancestral knowledge, has run through much of Hutchings’ work, both with Sons of Kemet, as well as with his other bands, The Comet Is Coming and Shabaka And The Ancestors. When I ask Hutchings about this, he says: “Where do we get our energy from? Not just the energy of the body, but in terms of energy for the mind. It’s not as if it springs out of nowhere. Some of that energy is given to you by the consideration of events or things that people have done in the past. So if you are inspired by someone, it means that their work is giving you energy. That’s the central tenet of ancestor worship – if you forget about those great deeds of the past, those deeds don’t have any bearing on your life.”

In the context of the album, this connection with ancestral knowledge is filtered through a specific reading of African history, particularly the work of Senegalese historian Cheikh Anta Diop, whose work, Hutchings says, sought to find “a unified centre to African ontological thought”. Diop argued that there were common cultural patterns in various parts of Africa, all of which had their roots in Ancient Egypt. “If you consider that humanity did start in Africa, then we’re trying to go to a point where we’re acknowledging what those principles are and seeing how we can contextualise them for our modern day”, Hutchings explains. “That’s why it’s called ‘To Never Forget The Source’, because if we forget where we’ve come from, then we’re just drifting off into confusion.”

From his studies of cultures across the continent, including the San of southern Africa, the Yoruba of modern-day Nigeria, and Kemetism (the mythology of ancient Egypt), Hutchings began to hone in on common spiritual and philosophical threads, in particular the idea of a distinction between a “subjective realm” and an “objective realm”. As he puts it: “everything within the material world, they would call that the objective realm”. But there is also a realm of things which aren’t formed, accessible to healers when they go into trance. “The whole idea of circularity is if you spend too much time in either one of those realms, then there’ll be an imbalance. There’s got to be a continuity going from one to the other to get sources of power.”

This expanded concept of what it is to gain ‘power’ was partly influenced by the work of Bajan poet Kamau Braithwaite. In 1984, Braithwaite introduced the idea of ‘nation language’ in his book, History Of The Voice, which was a critique of the dominant forms of literature and poetry that were being taught in the Caribbean. Nation language was a way to subvert the rigidity of poetic forms taught by the colonial education system, particularly those based on pentameter. Though nation language might be spoken in English, its syntax was closer to African linguistic rhythms, and was therefore better able to describe the experience of Caribbeans of African descent. According to Braithwaite, “It may be English: but often it is in an English which is like a howl, or a shout or a machine-gun or the wind or a wave.”

The band applied this critique of pentameter to music. “Pentameter is the grid, the framework”, says Hutchings. “Africans have always seen systems and found ways of subverting them. You’ve got to try to escape the grid in whatever you do.” This concept shaped how the album was recorded. “If you want to relate it to an aspect of how we make music, it would be related to that decision to not record to a click”, he says, “because it’s about the inconsistencies and how the music drifts. If something speeds up, it’s for a reason.”

At this point, Eddie Wakili-Hick chimes in: “There’s some research to suggest that [quantised music, recorded to a grid] can actually be bad for your health”, he says. “Milford Graves [the American jazz drummer and researcher] based his life research on this. His thing was looking into the rhythm of the heart, and he was able to derive pretty much any rhythm in the world from all the minute pulsations in the heart. As far as I understand his research, it led him to believe that by quantising a pulse to a metronomic tempo, it can have a negative effect on your health, because the human body isn’t supposed to function in a rigid, robotic way.”

Playing music in a way that feels intuitive and not bound by rigid rules – leaning into rhythms, tunings and frequencies that resonate with the players – has been central to the band’s way of working. “Every single thing you play in the compositional realm or the improvisational realm has to feel good, and that intuitive idea of what feels good is the healing. All that matters is – does it feel good, or does it not feel good?”, says Hutchings.

The ramifications of this approach are far-reaching: connecting to rhythms and melodies that feel natural shapes the experience of both the player and the listener. “The more you do things that feel good, the more you will be empowered”.

We’ve returned full circle, contemplating what it means for music to be ‘political’. “You’ve got to ask yourself: what is power? Power is the ability to influence your surroundings. So if you’re looking at Black Power, it’s the ability to influence your surroundings using the tenets of Black cosmology, and that can only be done by understanding what African ontological outlooks are and how they relate to us.”

Hutchings is wary of the label ‘political album’. “A lot of people say ‘this record or that record is political’, but everything is political, because all politics is is a way of organising life. So if someone creates an album called I Journey In The Dreary Meadows, because they’re trying to present a kind of utopia of middle-class suburbia, then that is also political, but it’s just not political with any sense of struggle.” Black To The Future is of course built around a very different vision. In the hands of Sons Of Kemet, music is not only a way to transmit information, but a vehicle for both inner and outer transformation, rooted in the struggles of the past, but always looking forward, to a more hopeful future.