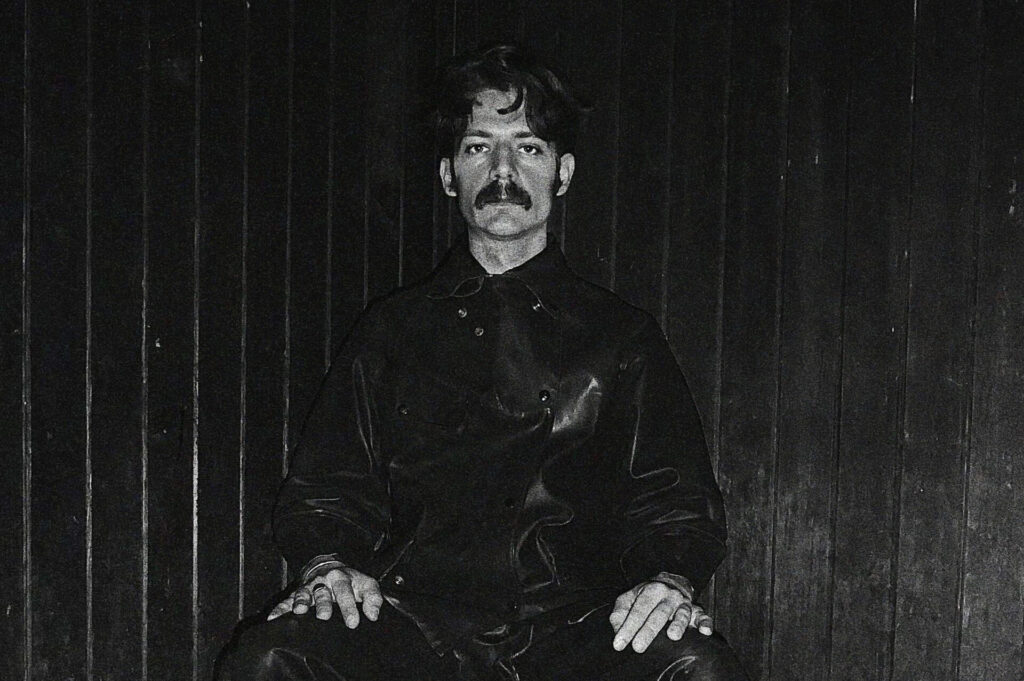

“I never expected anything to come out of it,” Daniel Foggin says candidly of his project Smote. “I would just put the release on Bandcamp when I felt done with it, because I liked making music.” Within a year he’d put out two EPs and two albums, at which point Matthew Baty of Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs messaged him saying Chris Reeder wanted his email. Among the keenest pair of ears in the business for spotting fresh talent brewing in the wild, Reeder and John O’Carroll, of Rocket Recordings, had recognised that this was the stuff of dreams willed into existence.

“I remember a few years earlier going to the Rocket 20 year celebration in London,” Foggin continues, “and I didn’t even own a musical instrument at the time. It’s pretty cool to be a part of that label now. I am still surprised to this day they put my stuff out, considering their standard.” Given the quality of Smote’s new double album A Grand Stream, however, it’s completely deserved. It’s an offensively good album, a finely cooked sound that brims with intoxicating organic flavours, intense depth, and a larger than life energy.

It’s the fourth in a string of records that have each carefully, though fiercely, evolved from the last. You could view his first two albums, Bodkin and Drommon, which take more from psych and folk, as the first phase, while A Grand Stream and its immediate predecessor Genog have moved things further towards heavy drone. He recalls the former two as being tied to the idea of intentional imperfections in the recordings, without obsessing about compression on drums or EQs. “It’s a human being playing the music, so why shouldn’t it sound like it?”

Now, Foggin lists the likes of Phil Niblock and Tony Conrad and contemporary figures like Kali Malone and ØXN among his inspirations. “I was lucky enough to see Phil Niblock before he passed away last year and that was an extremely heavy experience,” he tells tQ. Although different in terms of instrumentation, they share similar principles of tension and suspense. One of his other original influences were the groundbreaking Swedish psych pioneers Pärson Sound, and their later iterations as Trad, Gräs Och Stenar and International Harvester, a mysterious, informal group formed in 1967 in Stockholm, who held improvisational musical happenings where they combined raw, jammy psych with the minimalist ideas of Terry Riley and La Monte Young. Although Foggin keeps all his sonic projects under the Smote moniker (except for Yoke, a fun noisy project involving his brother), his freewheeling evolution, coupled with his resolutely DIY experimental approach to production, is similar in spirit. There’s a sense of excitement at the edge of chaos, but held together by the artistic focus at its heart.

As Smote’s songs weren’t initially intended to be played live, Foggin says. As he sought to translate them to the stage it was a fun experiment to take them to a practice room and flesh out the sound with a freely rotating group of musician friends. “Live, it’s a totally different beast! It’s supposed to be a happy experience, total sensory overload,” he exclaims, quick to praise the powerhouse skills of his musical collaborators to elevate things to a different level. They add new layers of heaviness to the basic exercise in tension vs release, until the sound reaches intimidating levels of grandeur.

A Grand Stream is the truest manifestation yet of Foggin’s original vision for the project since he embarked in 2020. It’s a primal modernist experience, perfectly blending ancient aural ritualism with contemporary sound art practice. It took shape during the summer of 2023, spent working at a farmhouse in Kelso in the Scottish Borders, with drummer Rob Law. “The title is very literal,” Foggin explains. “When we worked at the farm, there was a little stream coming down the valley, and every day when we finished we would go and sit in the sun and relax.”

I am instantly reminded of an illustration by Maurice Sendak for Ruth Krauss’ children’s book Open House For Butterflies, featuring a boy sitting beside a stream with a caption advocating for contemplation in a hectic world: “Everybody should be quiet near a little stream and listen.” Or perhaps loud near a grand stream? It all depends on the imagination and the intensity of the subjective experience. Contemplation doesn’t have to be bland.

As Henry Miller once remarked: “The moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome and indescribably magnificent world in itself.” I recall in my mind a scene that had a similar impact on me, returning from Dubrovnik to the island of Lopud where I worked in the summer of 2019. Approaching the island around 5pm on a small catamaran boat, everything was bathed in the day’s last intense wash of sunshine. In a transcendent moment of total immersion with life, it felt like I was restored back to planetary default settings, paradise regained. Such spontaneous transfiguration of the commonplace through poetic overpowerment is like a metaphysical gift, divine incursion exalting the senses.

“I believe a lot of things in life can be down to user experience,” Foggin continues, a little shy to admit to any profundity. “To anyone else, the stream would represent just another river but for us it was supreme joy.”

The intensity of such inner experience can be enhanced by formalised simplicity and ritualised routine. Basic foundations can become a launchpad for an energetic mental journey. This is true of Smote’s patient, mantric sound, which reaches transcendence through repetition, even though some might crave more formal variation.

“It’s good to have patience and sit with something for longer than is comfortable, as the sound changes and you start to hear different things. A lot of the songs on A Grand Stream would benefit from this attitude,” Foggin instructs. “Everyone experiences things differently, and that’s how I want the record to be experienced too.” He is devoted to creating an open sonic space for the listener’s reflection and to sharpen their perception.

Pioneering electronic composer Éliane Radigue explained it best, comparing such sounds to the surface of a river. “There’s an iridescence around the reefs, but it’s never completely the same, depending on the way in which you look, you see the golden flashes of the sun on the depths of the water. […] These kinds of sounds act as a mental mirror, they reflect the mood you are in at the time. If you are ready to open yourself up to them, to listen truly and devote yourself to listening, they have a fascinating magnetic power.” Her unique treatment of sounds was about giving them a reverence befitting real entities and trying to decipher what they are trying to say. A similar reverence can be applied to Smote’s sound, presented as a profoundly alive entity, with tales to tell beyond the flickering surface.

That sound also takes in a pastoral doom, a cosmic dirge that rips through heaven and earth alike. “The music is dark and foreboding but it doesn’t come from an unhappy place,” Foggin explains. Rather, it comes from the exploration and experience of rural living, both in sound practice and the farm work he and Law engaged in. It gets often romanticised, but as they spent a lot of time helping old farmers who were no longer able to work, one of the themes that emerged from their music was the hardship of physical labour and its effect on the body and life at large. There is a profound difference, the album proves, between simply being in nature as a visitor and meaningfully engaging with it.

Lighter, but no less epic aspects to the record’s worldbuilding come from the inspiration Smote drew from the tale of the Linton Wyrm – a mythical serpent whose lair was supposedly located just around the corner from the farm that Foggin and Law were working. In folklore, the wyrm was a fearsome creature that terrorised the local area, devouring livestock and causing general havoc until it was eventually slain in the 12th century by a local hero, John de Somerville. The monster’s writhing death throes are said to have carved out the unusual topography of the area’s hills. One can’t escape the subtext of the record as a hero’s journey of sorts; sonic dragons slain, our protagonists returning with a potent artistic elixir to liberate hidden inner streams of psychic strength.

Foggin is a direct and cooperative subject, open for the most part, and yet he still keeps some mysterious reserve. It all serves to give the listener greater autonomy in co-creating A Grand Stream‘s meaning, allowing them to gaze at the shimmering surface of their respective mental mirror. Its meandering sound captivates and disorients, like an ancient, consciousness-altering sound healing ritual. His use of vocal treatment is especially intriguing, producing untranslatable incantations that contain multitudes. He says he layers his vocals eight to 10 times, then processes them separately with different reverbs and delays in order to achieve a specific effect.

Especially fascinating is the eerie soul mining ambience of the drawn out intro to ‘Sitting Stone Pt.2’. It evokes Delia Derbyshire’s cursed dreamscapes, the cinematic sound design of Jan Švankmajer’s Alice or, most strikingly, Tom Waits’ creeping ‘What’s He Building?’. By the time you think, ‘we have the right to know!’, it mutates halfway through a controlled explosion into a grandiose wall of intoxicating guitar ambience.

‘Coming Out Of A Hedge Backwards’ and ‘Chantry’ are like a rural kosmische sound bath, exploring the meditative nature of repetitive work and post-labour respite that cleanse and ground one’s senses. I tell Foggin of my flirtation with gardening during lockdown, where I learned how important this grounding can be in keeping the body from pulling you into a depleted, depressed state. It’s something he seems to know instinctively, as evidenced in his treatment of sound. The grand finale of ‘The Opinion Of The Lamb Pt. 1 And 2’ is an unleashing; a fiercely upbeat, joyful festival of noise.

Smote’s austerity is one that refreshingly escapes the usual trappings of avant-garde music, simply by the force of its elemental vitality and its grounding of negative aural space. Its overpowering wall of sound still holds enough natural grace that it escapes the oppressive abusiveness of, say, Swans, and yet it is relentless in its forward thrust. “It’s all about the energy and pushing further,” Foggin concludes.

Smote’s new album is released on 23 August via Rocket. The band perform at this year’s Supernormal Festival, which takes place this weekend (2 to 4 August). For more info, click here.