There are precious few cultural institutions in Portland, Oregon nowadays that one might call sacred. Once something of a rock & roll never-never land, the city in recent years has become a haven for more-norm-than-normcore tech workers and other bourgeois refugees from around the world, and with that "progress" has inevitably come the bulldozing of a glorious, unscrubbed history. All-ages venues are basically a thing of the past. Voodoo Doughnut, Portland’s once-gnarly fried carbs dispensary (and a business owned, incidentally, by one of the founders of scrappy 1990s venue the X-Ray Cafe), was expanded and tidied when its core clientele shifted from bedraggled punks to suburbanites and tourists who’d heard about them on the Food Network. Near the heart of town once stood the recording studio where the Kingsmen laid down their rendition of ‘Louie Louie’, that sacred writ for punk’s bad-is-good ethos and a feather in a town’s cap if ever there was one; that same building is now dominated by a fucking Shinola storefront (though it’s admittedly to their credit that they’ve yet to remove the commemorative plaque).

Mind, there are still rockers and weirdos in Portland, and many of them still pay due respect to those giants who have walked these soggy boulevards before: The Wipers, Poison Idea, Neo Boys, and especially Dead Moon. Yet, as economic circumstances continue to push out the city’s truest, bluest freaks, increasingly lost in the shuffle is the Portland institution who predated all of the aforementioned groups, outlasted all of them, and created a body of work which has done more than anyone’s to manifest the long-failed bumper sticker dictum to "KEEP PORTLAND WEIRD!"

I’m talking, of course, about Smegma, a group which I have long contended will prove Portland’s most lasting and vital musical legacy of the last half-century when time outs the truth. Their woozy free rock is borne of a recipe which dips a ladle deep into classic American gumbo, dishing out tender vittles of The Art Ensemble of Chicago, Slim Gaillard and Link Wray in equal measures, while adding exotic spices like Kurt Schwitters and Pierre Schaeffer for taste. Just add a dash of punk’s wilful amateurism and unpretentiousness, spoon in the broadest guest list this side of a John Zorn record, and serve hot. How many bands, after all, can you name whose lineup has included members of both hardcore godheads Poison Idea and Paisley Underground heroes The Dream Syndicate, a good chunk of the Los Angeles Free Music Society, and even Herbie Mann’s former drummer? Who have featured not one, but two, renowned authors/Blue Öyster Cult lyricists (experimental writer and ground-zero rock crit Richard Meltzer, and cyberpunk early adopter John Shirley) as vocalists? Whose lengthy list of collaborators is broad and deep enough to include the late LA outsider Larry "Wild Man" Fischer and Detroit trip metal (excuse me, psychojazz) kingpins Wolf Eyes, not to mention experimental heavies like Merzbow and John Wiese? Whose core members still invite old pals and young turks alike (full disclosure: I’ve been lucky to be one of the latter) into the sitting room of their hot pink house to engage in stoned-to-the-gills sound freakery? Surely, all of this has lent the band a coveted rep among noise dweebs, experimental hardliners and addled punks worldwide. Now, if only it did better than dick for them in Portland these days…

Here’s a little history for the uninitiated:

Smegma was founded in Pasadena, California in 1973, but moved to Oregon two years later. Back then, virtually nobody thought it was cool to be in a band made up primarily of non-musicians, much less one that combined fried free improv moves with nods to straight 1950s rock & roll, and the approach made them few friends or fans at the outset. "If we played at a party [in the 1970s], there would be a riot", said Ju Suk Reet Meate (né Eric Stewart) – the only current member of Smegma who has been consistently in the group since day one – on a recent visit to the aforementioned pink house in Northeast Portland which used to house the whole band, and which he still shares with longtime partner and bandmate Oblivia (AKA Rock & Roll Jackie, AKA Jackie Stewart). "People would hate us, and be physically threatening! People didn’t put up with weirdo shit."

When the band first moved into this neighbourhood, they were practically an invasive species. Until the mid-1990s or so, Portland was a very different place: as Oblivia puts it, "It was a blown out, half vacant city. There were so many empty buildings, so much nothing." Shows and artistic activities at that time were mostly clustered downtown; to be a weirdo artist type and move towards the edges of town back then was to raise eyebrows. "(Our neighbors) thought we were crazy. They didn’t think we were crazy, they were sure we were crazy."

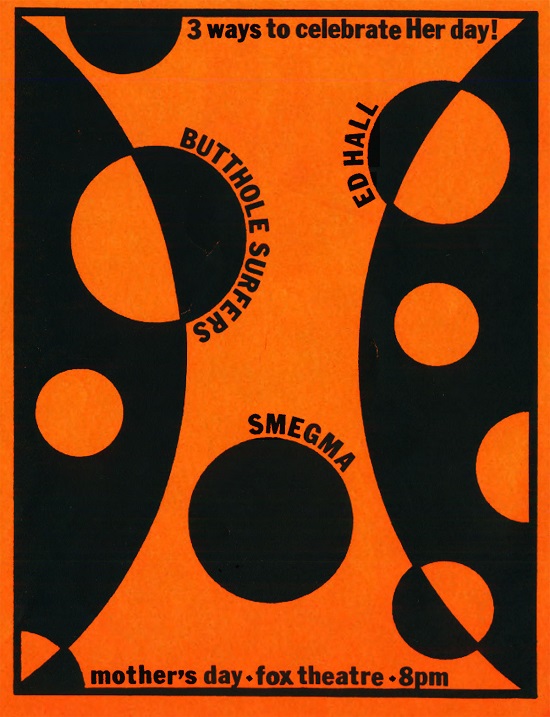

It wasn’t until punk rock had first reared its pimply head towards the Pacific Northwest that Smegma found a space where their addled sounds were appreciated. They became a lynchpin in Portland’s tight-knit alternative community, routinely requested as openers by The Butthole Surfers and the Dead Kennedys. They were on the bill at the second-ever Wipers gig, early enough where it was still hard to tell if they were even a good band or not. In 1988, Smegma were so respected that they were voted Portland’s Best Band by readers of local alt-weekly The Willamette Week and sent to a festival in Toronto as the city’s representatives, and were also invited to play the Portland Mayor’s Ball.

"To find a scene of any sort that would embrace [Smegma] was a mighty tall order, but they held fast and endured," Ace Farren Ford, a founding member of the band who officially rejoined in 2007 – and also a founding member of the Los Angeles Free Music Society – said in an online interview. "They found acceptance in the Portland punk scene. It really amazed me how they developed."

Around the same time, Smegma also made their first tenuous connections with European sound explorers sympathetic to their style, somehow finding themselves on the Nurse With Wound List, the now-legendary index of musical outcasts included as an insert with that project’s debut LP Chance Meeting On A Dissecting Table Of A Sewing Machine And An Umbrella. A nice gesture, to be sure, but not one that seemed to portend much of anything at the time. "When it happened, they were contemporaries. It didn’t really resonate, because nobody really knew that that was a scene," says Ju Suk Reet Meate. "Somehow, they (Nurse With Wound and other European contemporaries) reached out to us, so we kind of knew there was something else going on, though it wasn’t like us. We were being reached out to and thought of as equals on some "art music" level. I would say that that was the very first time that the world had responded to us as if we were, indeed, some sort of art music."

"Since then, I think people assume that there’s always been some folk music avant garde – as opposed to the academic, fancy-pants, musician-based avant garde – and when we started, that did not exist in any way. With modern noise, there are a lot of levels where people know that it exists, even though it’s a tiny niche; still, it’s an absolute fact that that’s a thing. That list was the first step in that inexorable march towards inclusiveness, in a strange way."

Though their important place in the history of vernacular/folk avant garde music might not carry much cachet in Portland 2.0 (subtitle: The Artisanal Salt Years), there is still a keen interest in certain corners when it comes to preserving Smegma’s history. Aside from a slow trickle of archival releases on the band’s own Pigface label, an elusive Italian label with an ever-mutating moniker has also been preparing a few vinyl pressings of vintage unreleased Smegma material at press time. Rumors also abound about an impending reissue of rare material by founding member Ju Suk Reet Meate’s early ’80s post-punk side band, Jungle Nausea.

In the past, it might not be like the members of Smegma to spend so much time marinating in the juices of their past. Now that the group is spread across two states (of the current regular lineup, Ju Suk Reet Meate, Oblivia, and Madelyn Villano still reside in Portland, while Ace Farren Ford and Dennis Duck are based in California), though, much of the time that might otherwise be spent jamming is spent wading through the archives. "There’s a lull in new recording at the moment, but we did put out four or five records in the last five or six years. By Smegma standards, that’s high output," Ju Suk Reet Meate says. "Back in our classic era, five years was the minimum we’d wait before putting out another record. We wanted to wait until we were doing something completely different!"

The experience of looking back has proven rewarding. Ju Suk Reet Meate happily admits that, like most bands, Smegma’s salad days were among their best as a band. "The first couple years you try to do something, there’s an extra purity of spirit, of essence, that you can never quite recover. No matter how much better you get as far as musicianship, editing, all the things you can improve upon, it doesn’t really address whatever that intangible is."

It took Smegma a few years to adapt to the Pacific Northwest. When they first left California, the LA freak scene which gave the world Captain Beefheart and Frank Zappa was on the wane, and they cast their eye towards the Pacific Northwest for new inspiration (ie. wilderness, weed, etc.) Post-hippie LA’s vibrant weirdness nonetheless looms large in the Smegma mythos. "I was blessed to have been friends with Don Van Vliet (Captain Beefheart) since I was 15," remembers Ace Farren Ford, seemingly still in awe. "The times I shared in his presence were magic. He inspired me to no end."

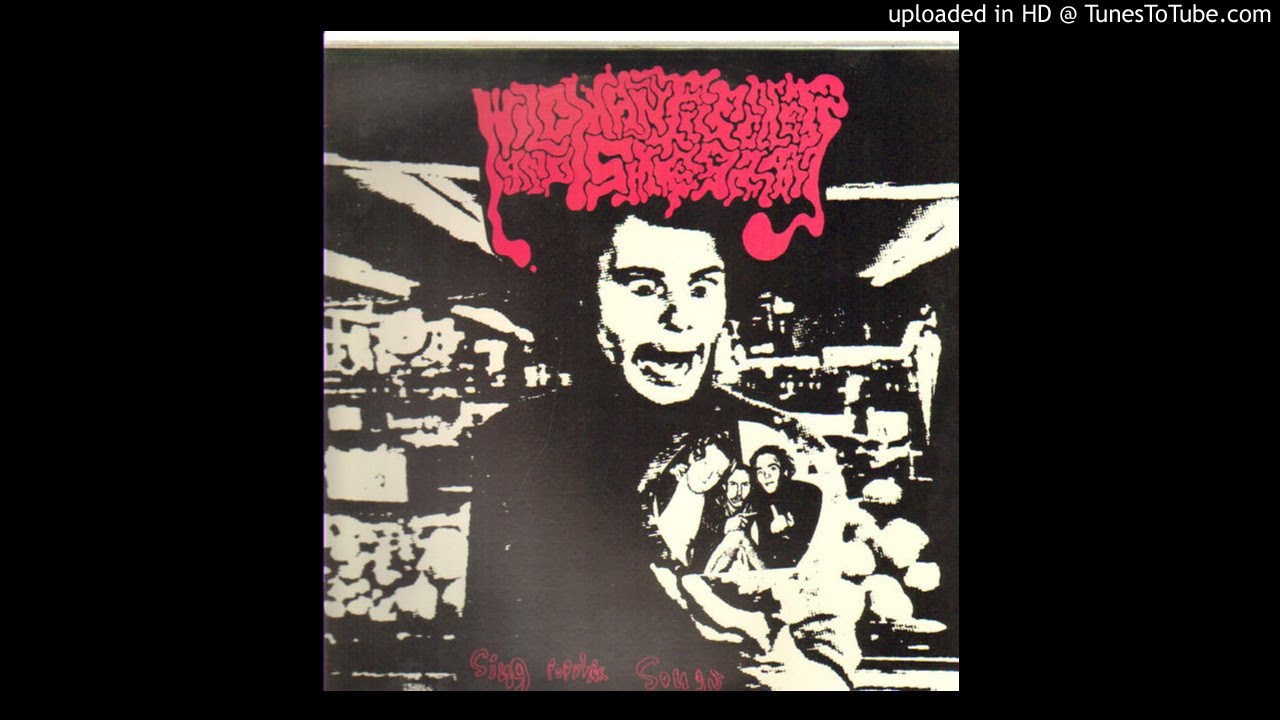

Ford’s association with Van Vliet never resulted in the monstrous dream of a Beefheart/Smegma jam (though Van Vliet did do the cover art for the bedrock LAFMS compilation Blorp Esette, which contains some prime early Smegma), but shared connections were likely what resulted in the band’s pre-Portland jam sessions with Wild Man Fischer, documented in part on the 1998 collection Wild Man Fischer And Smegma Sing Popular Songs. Fischer’s child-like approach to songcraft and Smegma’s wonky improvisation were a match made in heaven, at least for a few days. "[Fischer] fit into Smegma in a visceral, absolutely pure way, on every level except that he was unbelievably annoying", says Ju Suk Reet Meate. "He was willing to experiment".

"When we jammed with him, he was so completely in the moment," he continues. "He played every single instrument, he would make up songs that he’d never done before and would never do again. He just came alive. He wanted to be the life of the party, and if he could actually be that, boy, would he light up! That was such an amazing moment. Within a couple days, though, he was eating all our food, and telling the same ‘Frank Zappa is an asshole’ stories too many times, and we realised that he needed to move on to the next place for awhile."

More than two decades later, Smegma found themselves inviting yet another rock & roll cult favorite to front the band: former rock critic, writer, and provocateur Richard Meltzer. Though he’s had a long career writing outside of music circles, Meltzer is most well-known by many as the author of the dense and groundbreaking The Aesthetics Of Rock and for the abrasive, stream-of-consciousness approach to rockwrite he shared with his friend/ contemporary/ primary competitor Lester Bangs. His only noted prior credit as a vocalist before Smegma was in the short-lived LA punk concern Vom (who, sans Meltzer, went on to become the Angry Samoans). Meltzer had quietly relocated to Portland sometime after that. "I remember going to a house party and seeing Richard doing a reading, and he mentioned the LAFMS people, and I realized he was THE Richard Meltzer," explains Ju Suk Reet Meate. "We asked him to drop by, and he wound up being in the band for seven years." Meltzer’s vulgarian streak and penchant for the Dionysian didn’t always win the group new fans in Portland’s increasingly polite environs, but it did afford them a chance to revel in Meltzer’s direct connection to pre-Woodstock rock & roll.

"There has always been a strange connection between Smegma and straight ’50s rock & roll," Ju Suk Reet Meate says. "Back when we were this totally wacked band that couldn’t do anything at all, we would beg some guitar player to come in and play straight riffs." This connection and dedication to rock’s perverted past is much of what gave Smegma the ability to connect during the punk era: for all their experimental leanings, Smegma were basically a classic rock & roll band, albeit a supremely fucked-up one. What could be more punk, really?

Smegma’s current preoccupation with combing their archives might make it seem as though the group is effectively a done deal, or worse, a nostalgia act. Not so. Though the band is not as prolific in a given year as they used to be (Oblivia: "Usually there’s a record and a concert. We try to do one performance per year."), what they do is always fresh. "I think in the time of the current lineup, we have made some of the best music Smegma has ever made," says Ace Farren Ford, "and I have always been fond of everything the band had ever done". Recent performances have included trips to Oberlin, Ohio to perform with Hanson Records founder/ex-Wolf Eyes guy Aaron Dilloway (who, incidentally, is the person who first introduced me to Smegma’s catalogue, and who was busy globetrotting and/or running the Hanson Records brick-and-mortar store when I attempted to talk to him for this story) and a show in Los Angeles with John Wiese sitting in.

Ju Suk Reet Meate and Oblivia also continue to perform regularly as a duo, The Tenses, which operate as a kind of a travel-size analogue to Smegma. "I personally tend to think of The Tenses as the chamber ensemble version," says Ju Suk Reet Meate. "Everything is meant to be clear. If something’s in the background, it’s because it’s part of the aesthetic, not because it’s being drowned out."

It’s easier to maintain that kind of equanimity in a duo than in a larger group, but Smegma seems to be chugging along healthily these days. Gone is any of the band drama which yielded a major lineup change some years back (a sensitive subject among the members I talked to); as Oblivia puts it, "We all get along, we all like each other very much, and we’re all really happy with this band." Still, the work done in those tense, intimate, prolific early days has done much to secure their enduring oddball legacy, even if it’s sometimes to the band’s own bemusement. "Pretty much everyone involved in it looks back and says ‘What possessed us to do that?’", says Oblivia. "It’s great, and everyone to do this day agrees that it was great, but nobody knows why [we] did it."