All photographs courtesy of Philippe Carly’s New Wave Photos

After the release of ‘Alice’ in November 1982, The Sisters of Mercy entered their first golden age. It lasted 12 glorious months.

That year was strewn with brilliant singles, EPs and legendary live shows. By the end of it, they stood as one of Britain’s premier independent bands, with a nationwide hardcore following and were ready to make the transition to rock stardom. The Sisters were already cloaked in a powerful mystique that intersected with some of the mythic nodes of rock: the NYC of The Velvets, Suicide and The Ramones; the Detroit of the MC5 and The Stooges; and the LA of The Doors.

Yet, this unlikely ascent was incubated in a non-descript semi-detached house in an area of north-west Leeds better known for its high concentration of students and takeaways than rock action.

Leeds – one of the least lauded cities with a post-punk scene – was at the time being laid waste by the pyroclastic cloud of Thatcherism. It had places for bands to play, but it didn’t have a decent recording studio. So The Sisters made their records in Bridlington, a Yorkshire resort town, in an 8-track studio near the seafront.

Nor did Leeds even have a record label. So The Sisters started their own and ran it as a cottage industry out of that self-same semi.

Yet, The Sisters remained steadfastly a Leeds band during their golden year, even as they outgrew the city that had birthed and nurtured them. The bond between band and city were unshakeable. For all its shortcomings, Leeds made The Sisters.

As their own shortcomings made The Sisters too. When things did click during 1982 and 1983, they were operating on a shoestring budget and with limited musical ability. Their equipment was primitive – sometimes borrowed, sometimes homemade, often junk – and playing their own repertoire properly was often a stretch for them.

“It was sort of punk. Very basic,” remembers their bass guitarist Craig Adams. “We didn’t really know what we were doing. We were just making it up as we went along, but you catch some bands early and they have this energy and this thrust.”

Nor could The Sisters afford a graphic designer, so they created their own logos, posters and record covers with Letraset sheets, Pantone colour charts and by deploying found images: the sleeve of an Alice Cooper album, an anatomy textbook, a photo in National Geographic and a print of a Matisse Blue Nude.

In November 1983, The Sisters and The Smiths were in similar, if trans-Pennine, positions: both bound for glory, yet still to make an album, their reputations based on the stage and short-form vinyl. Both bands’ most recent singles – ‘Temple Of Love’ and ‘This Charming Man’ – had just been to Number 1 in the Indie Charts.

Yet, the Sisters’ rise – unlike that of The Smiths – had been a slog. The Sisters in some form or other had existed since 1980 and had meandered through two years of intermittent gigging and sundry line-up changes without much attention being paid to them.

However, long before they became a great band, they were a great idea. In their golden year, the two came together. Thought became deed: The Sisters murdered rock & roll and kept it vibrantly alive at precisely the same time.

Their ascent would not have been possible without their own peculiar tastes and talents but it also depended upon the fervour of their friends, the myriad kindnesses of strangers and the devotion of their followers.

“Damn right, we were formidable then,” believes Gary Marx, The Sisters’ guitarist. “We had some good tunes but it was always about much more than the notes.”

“I knew the band was bigger and better than the four of us.”

This is that story.

On April 23, 1983 – The Sisters of Mercy played a gig in in the sports hall of the Technical College in Peterborough, a town, then as now, rarely visited by travelling rock bands.

These unlikely environs witnessed the band at their live peak, an encapsulation of what was special, even odd, about them.

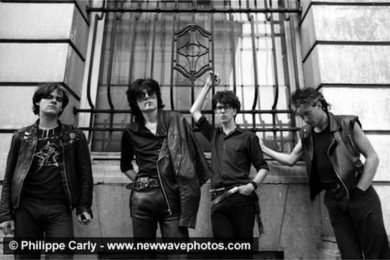

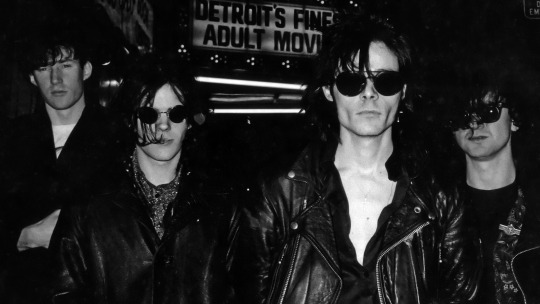

Firstly, there was the austerity of the visual presentation: no smoke, minimal light show, no drummer, not much backline, just four men virtually in a row. Left to right: Marx, the lead guitar player; Andrew Eldritch the singer; Adams the bass player; Ben Gunn, the second guitarist.

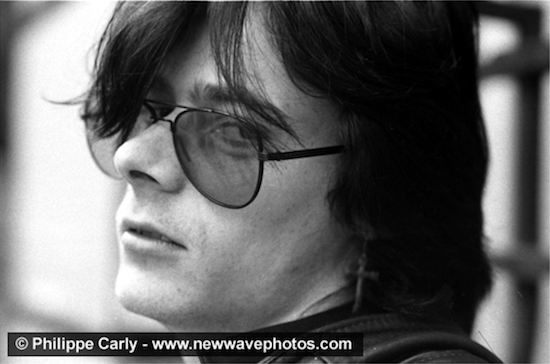

The key dialectic was stage right: Marx, tall and broad-shouldered, winkle-picker held together by gaffer tape charging around slashing at his guitar and Eldritch in shades, a riot of black leather, svelte and sinuous, wafting his cigarette around, manipulating his mic stand and twitching his crotch.

“In terms of what I brought to the party,” Marx recalls. “Most obviously I wasn’t Andrew.”

Adams and Gunn and a Roland TR-808 drum machine, christened like all its predecessors Doktor Avalanche, held things down while the Marx/Eldritch dichotomy ran rampant.

Marx refers to it as him playing “Dave Hill to his Alvin Stardust in some weird Glam era mash-up. Or Rob Davis to his Les Gray gives some idea of the incongruity of us as a pairing.”

Marx’s analogies also give a sense of how far Eldritch was prepared to push his stage act into the ridiculous, but not how sexy it was. Eldritch was both Billy Fury and his own Larry Parnes. He had gone deep into the homoerotic, past The Ramones street hustler look all the way into Warholian fetish and Scorpio Rising. This failed to make Eldritch a gay icon, but it was industrial grade catnip for some straight women.

Adams, still only 20, was the most accomplished – in fact the only – musician in the band, but chose to play his bass in the most brutal way possible, aping Michael Davis and Lemmy. Adams was key to The Sisters’ sound. As Eldritch told tQ last year, “he just naturally took to fuzz bass, which is an instrument and attitude all of its own. And he was bloody good at it.”

As later line-ups would prove, Sisters’ songs could easily be played by one guitarist. That The Sisters used two meant that their sound could either feel deconstructed or be in lock step, a wall of distorted sound. The second guitarist, Ben Gunn – the band’s virtually motionless Hank Marvin – although “living on crumbs”, as Marx puts it, was vital. “History will show,” says Marx, “that he’s there on the best records and all those fantastic gigs. While not exactly being central he was certainly crucial. In much the same way that my chief contribution was not being Andrew, Ben was not any of us.”

Also, as Marx admits, “of course, we were five in total. As dumb as it sounds, the drum machine was a massive part of the band’s personality.” The Doktor in his 808 incarnation was both cutting edge and primitive. It took a lot of effort, as Eldritch told tQ last year, for him “to sound other than pip pip pop … like anything other than Soft Cell. It’s great for them but we didn’t want that type of landscape.” To make the Doktor “solid and smacky” live and “to get some wallop in”, he was DI’ed (direct injected) into the PA, not via one of The Sisters crummy amps.

The Doktor could not play anything complicated, even if his programmer wanted him to. And the programmer did not. As much as Eldritch loved bands that obviously had brilliant drummers – Ian Paice, Simon King, Phil ‘Philthy Animal’ Taylor, John Bonham – it was Mike Leander’s Glitterbeat to which Eldritch was most in thrall. Thus, The Doktor (was) operated in the realm of the genius dum-dum boy and girl drummers like Nick Knox, Tommy Ramone, Moe Tucker, Scott Asheton and whatever Martin Rev had rigged up to make drum noises in Suicide.

The overall effect was unrelenting. The band played each song with the same guitars, through the same couple of pedals; The Doktor couldn’t change tempo mid-song, sometimes just playing the same pattern ad infinitum; Eldritch sang in a less-than-two octave range and Adams kept as close to the root notes of chords as possible.

The cumulative effect could be extraordinary.

The four men on stage were the central but not the only component of The Sisters set-up in 1983. Also part of what Marx calls “the inner circle” were the roadies Danny Horigan and Jez Webb, the driver Steve Watson, the über-fans Dave Beer and Ali Cooke, and Claire Shearsby, who as well as being Eldritch’s girlfriend of long-standing, had “assumed the role of engineer.” Marx recalls that “at first she would mostly concentrate on dealing with Andrew’s voice and timing delays for the space-echo on different numbers. She then grew in confidence and muscled in on the desk because more often than not the in-house engineer would be killing us.”

Like many of the 1983 shows, the one in Peterborough began in extremely bold fashion with ‘Kiss The Carpet’, one of their very slowest and sparsest songs. Pushing the already austere aesthetic even further tested the nerve of the band.

“It was an edgy way to start,” recalls Marx. “I often looked across at Ben who seemed a bit unsure how to behave when he was doing so little.”

There were also practical reasons.

“It certainly made good sense to introduce elements one by one,” Marx continues, “to leave plenty of time and space to sort out technical problems. It gave me a little time to feel my way in. I can hardly overstate the fact I was often playing stuff that was tricky for me to do sitting down and concentrating, never mind when I was revved up and trying to throw a shape or two.”

Nor did The Sisters shy away from other slower, then unreleased, songs in their repertoire like ‘Valentine’, ‘Heartland’ and ‘Burn’, but the bulk of the set in Peterborough was full throttle, riff-heavy and more familiar: ‘Alice’, ‘Anaconda’, ‘Body Electric’, ‘Adrenochrome’, ‘Floorshow’.

As well as closing with ‘Sister Ray’, there were other excellent cover versions: ‘Jolene’ and ‘Gimme Shelter’.

In Peterborough, The Sisters skipped their version of Hot Chocolate’s ‘Emma’ – the usual centrepiece of their show – and ‘Lights’, another slow-burner. ‘Damage Done’ and ‘Watch’, from their very first – and very bad – first single, and The Stooges’ ‘1969’ had already been dropped from their set by this point.

Later in the year they would add ‘Temple Of Love’ and work ‘Louie Louie’ and Suicide’s ‘Ghost Rider’ into a final encore medley with ‘Sister Ray’.

The “inner circle” was a full of fun but, like a street-gang, it also carried with it more than a whiff of aggression. Marx explains: “Some of it was territorial, as the Yorkshire-based following took over a venue. Equally, there were aspects of the band’s personalities that could be the trigger for it. Craig in particular had a very short fuse.”

Hi-jinks and violence were in evidence in rapid succession during ‘Floorshow’ in Peterborough.

“There was a throwback punk kid stood in the front of Andrew,” recalls Marx, “who had some connection with a local band on the bill and had the big spiked hair and The Exploited or some such stencilled on his leather jacket.”

The punk was staring too intently or mouthed something or spat – his exact infraction had been forgotten – but as Adams began the opening heavy Motörhead-like chords of ‘Floorshow’ the punk attempted to climb up on to the stage.

Adams let go of his instrument, rushed forward and kicked him in the face. As the punk scurried off the stage, Adams carried on with ‘Floorshow’. Justice had been swift: Adams had only missed out one bar.

While Adams was still guarding the front of the stage and eyeballing the locals, Beer and Cooke ran on stage and shoved custard pies – paper plates full of shaving foam – onto the heads of Marx and Gunn. “I think they were going to do Craig and Andrew as well,” recalls Marx, “but sensed they weren’t exactly in the mood.”

“The gig had a definite mood shift,” Marx recalls. “Craig played out of his skin for the rest of the show. Something clicked for Andrew as well.”

For Marx too. Always the boisterous performer, he ended the show sprawled on his back having slipped over in the remnants of the shaving foam.

The show was recorded on VHS video from a balcony at the rear of the sports hall. So too was its aftermath. The camera kept running as the DJ played a King Sunny Adé track.

“The punk throwback returned with his nose splattered,” remembers Marx. “He had obviously rallied all these mates of his from the area.”

After initially loitering back stage The Sisters and their inner circle soon had enough and decided to bring things to a head. “The camera recorded us all coming out for the showdown,” says Marx.

This included Shearsby, instantly recognisable by her peroxide blonde hair. “Physically she could handle herself; she’d been a PE teacher,” states Adams. “She could have smacked any of us out easily.”

The Peterborough punks huffed and puffed a bit but ultimately turned and ran,” remembers Marx.

“We did look kind of magnificent. I use the word advisedly because it was more like those Samurai or Western films. Shot from above with all of us walking through the frame at some point: Steve, Claire, Danny, Andrew, Dave and Ali, and Craig of course – all these special people.”

This dust-up took place in the middle of a tour supporting the Gun Club, although that night The Sisters were off on their own while The Gun Club were in Sheffield. The next night they rejoined at the Lyceum Ballroom in London, where, again, “everything seemed to click,” Eldritch told Sounds in February 1986.

The match-up of the two bands made sense, although they sounded wildly different. Both ran unlikely elements of rock’s heritage through the post-punk blender: American roots music in the Gun Club’s case, stomping glam and hard rock in The Sisters’.

In addition, The Sisters of Mercy and the Gun Club were both fronted by highly literate young men, who wrote superb lyrics and delivered them in idiosyncratic vocal styles.

The Sisters might not have been note perfect by the spring of 1983, but increasingly regular gigging had sharpened them up no end. They were the equals of the Gun Club, themselves a ferocious live act. The Sisters had indeed come a long way from the litany of cock-ups and debacles that littered 1981 and much of 1982.

Before this crucial tour, it had become apparent that The Sisters were working as a live proposition beyond their West Yorkshire homeland, especially in The Midlands. “There were some wild gigs in late 82 and early 83 – two Birmingham shows were riotous,” says Marx. “The second in particular I remember as being great.” These were at the Bournbrook Hotel in Selly Oak and the Fighting Cocks pub in Moseley.

“Similarly the London shows (either side of Christmas 1982: The National Ballroom, Kilburn; Klub Foot in Hammersmith and The Lyceum) were all right up there.” Long gone were the days when Marx felt the The Sisters “were hicks from the sticks” when they played in the capital.

The visual identity of the band had also pulled together. Marx recalls that “on the third date of the Gun Club tour in Norwich, we were all getting ready in the tiny dressing-room and Andrew looked into the mirror and said, ‘Finally we look like a band.’”

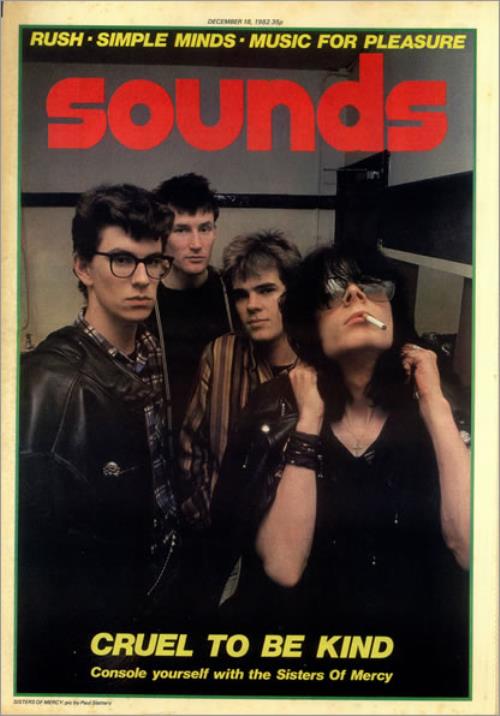

Marx explains: “When we started, it was still so close to the height of punk that I stubbornly stuck to that idea of avoiding what I saw as the trappings of rock stardom. The Sounds cover shot (in December 1982) gave a fair indication, with Andrew up front looking like Johnny Thunders and I’m behind him with a basin-cut and one of my dad’s old cardigans. I soon got sick of looking like the village idiot and any principles got the squeeze.”

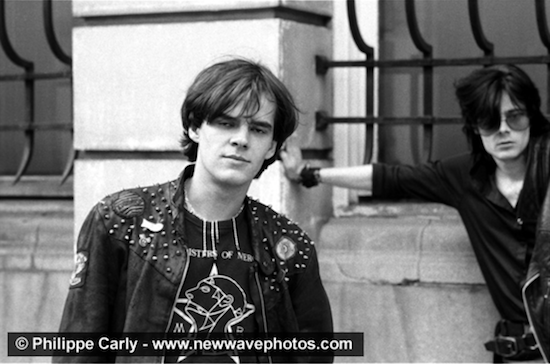

Even with a more cohesive identity, The Sisters were a long way from the more uniform presentation of 1984/5. Ben Gunn alone guaranteed that.

He was young and looked it. He’d joined The Sisters when he was in his final year of school and at the time of the Peterborough show was in a kind of gap year between his A Levels and university.

“He was so clean-cut and at odds with the perception of what the band was about,” says Marx. “That never made us think twice about inviting him in.”

Sometimes the incongruity could be extreme. “When we supported Nico in London, we had to promise his mum we’d get him on the last train home because he had an English exam the next day,” says Adams. He also remembers that “Ben’s mum drove The Sisters in her Volvo estate to support The Clash at Newcastle City Hall.”

The Gun Club tour also resulted in another of Marx’s not infrequent Sisters-related injuries.

While out front watching the headliners in Newcastle, “I felt this whack, as if someone had hit my arm with a mallet. Next thing I knew I was pouring with blood. The guy – who was nowhere to be seen – had broken a glass and jabbed it into my arm. I was whisked off to the hospital and for a while no-one from the band knew what the hell had happened to me.”

In the month before the Gun Club tour The Sisters had played at Franc’s in Colne, near Burnley, that also involved bloodletting.

“Franc’s was tiny,” says Marx “and when you got there you had to help assemble a small stage out of plastic beer crates and plywood. The gig was great, but as Craig and I got more and more into it we lurched ever nearer with the headstocks of our guitars until finally we both turned too quickly and he hit me right above my eye with the end of his bass, splitting the brow Henry Cooper-style. I decided to administer some First Aid Sisters-style: I rubbed speed straight into the gaping cut as a sort of act of experimentation and bravado. ‘Tonight Matthew, I am Iggy Pop.’ In bloody Colne.”

One of the reasons for Eldritch’s approbation in Norwich was that it was one of the few times Marx wore sunglasses onstage. Eldritch was well-practised at this but Marx was not. “I fell off the side,” he says. “Thankfully it was only a very low riser.” Eldritch had also mastered the even trickier stage business of smoking in gloves.

During their golden year, gigs in tiny or relatively obscure places in the UK like Franc’s, Peterborough Technical College, The Fighting Cocks, The Bournbrook Hotel and The Porterhouse in Retford were becoming less frequent as The Sisters plugged more and more into the established university and polytechnic circuit (those in Sheffield, Coventry, Kingston, London in 1983) and into venues well entrenched in tour schedules (Night Moves in Glasgow; Brixton Ace; and the Dingwalls chain). Yet there were still oddities: Solitaire in Swindon, which only a few people came to, and The Union Rowing Club in Nottingham, which was packed.

As the golden year progressed, other occasional crew members became more regular fixtures, especially Pete Turner, as front of house sound engineer and Phil Wiffin, who was the lighting designer. Turner had been doing the sound at a CND benefit in Alcuin College in York University in February 1981 when The Sisters played live for the first time. The relationship that began then lasted decades.

Phil Wiffin – who would also become another long term resident in the world of The Sisters – “instantly got what we were shooting for,” says Marx. “He was a good influence on the road, smart and funny, very calm – he could keep Andrew ticking over.”

Both Turner and Wiffin were connected to The Sisters via Ken Giles, who owned KG Music Studios, the recording studio in Bridlington which The Sisters used for their early records. “We couldn’t always afford the Bridlington boys on those early gigs but if we had any room at all in the budget – sometimes when we didn’t – we would call KG,” remembers Marx.

After the Gun Club tour, The Sisters returned to their Yorkshire heartland. Adams shared a flat with Simon Denbigh of The March Violets in Hyde Park in Leeds, Gunn lived with his parents in Otley, a small town north west of Leeds en route to the Yorkshire Dales and Marx, Eldritch and Shearsby shared a house – 7, Village Place – in Burley, also in Leeds.

Their rooms had signs on: Claire’s Room, Marks’s Room, Andy’s Room.

Gary Marx’s real name is Mark Pearman.

Eldritch’s is Andy Taylor.

Gunn’s is Ben Matthews.

Adams was the only member of The Sisters using his real name.

Of all the places in Leeds that are key to The Sisters’ story, 7 Village Place was the epicentre. Eldritch, Shearsby and Marx had shared it since 1981. Marx has a memory of decorating it listening to No Sleep ‘til Hammersmith, which had just come out.

“The popular myth appears to be of Hunter S. Thompson taking over Bruce Wayne’s Batcave,” states Marx, “with hi-tech excess being the order of the day. The curtains downstairs stayed closed at the front of the house all the time, which no doubt gave it the air of a drug-den. It had its moments but nothing to ring Ross and Norris McWhirter (co-founders of The Guinness Book Of World Records) about.”

“The reality is that it was in a quiet street of about 20 houses and our neighbours – Jack and Nora – were people we got on well with, amazingly given the racket they had to tolerate.”

Also, injecting some reality into the myth, Adams says that, “we played football in the park nearby which was hysterical, seeing Andrew Eldritch, Gary Marx and me all with stupid haircuts trying to play soccer in winklepickers.”

“It was a really dirty house,” Danny Horigan remembers. “There’d be dust everywhere. The magnolia colour of the walls wasn’t paint; Andy and Claire used to smoke constantly.”

“The main living area was dominated by Andrew’s collections of books, VHS tapes and cassettes,” says Marx. “He had all these Penguin Classics arranged in order with the pale blue or orange spines.” Eldritch also indulged other favourite pastimes in the sitting room of Village Place: completing The Times Crossword and writing messages on postcards in his distinctive elongated handwriting.

The Sisters also rehearsed in the very small cellar, which could be accessed via the sitting room. “I don’t remember us rehearsing as a full line-up or even more than two people together at any given time,” says Marx. This was partly due to space restrictions “but also because Andrew could easily be fast asleep in the living-room above.”

As the year progressed, Eldritch ventured more and more into the cellar on his own to work on songs. It was also where he practised the screams that peppered Sisters’ tunes.

This was most likely at night.

“Andrew lived a nocturnal existence,” recalls Marx, “which required much more focus and planning back then. TV closed down around midnight, so there was continual recording of TV shows and hiring of videos to watch through the early hours.”

“The TV was never not on”, says Adams. Episodes of Blake’s Seven, Hogan’s Heroes and On The Buses were viewed over and over.

And there were drugs, of course. Leeds was, after all, the speed capital of England.

“The speed wasn’t cheap but it was very good,” Horigan states. ”Very professional. Not much of that shit speed that makes your teeth itch.” Amphetamine was not good for the immune system, but should you be so inclined, as Eldritch was, it was perfect for staying up night after night in 7, Village Place drafting and redrafting lyrics, tinkering with The Doktor or playing one’s trusty Woolworth’s guitar.

As well as possessing a bargain basement instrument, Eldritch was not a very good guitar player “but sometimes when you’re not a very good guitar-player you have to use your imagination more,” says future-Sister Wayne Hussey. “When I started rehearsing and pulling the songs apart, I started to realise how clever some of the guitar parts were.”

Marx acknowledges that Eldritch “was pretty rudimentary” but even so “in those first two years, aside from a few hard rock party-pieces of Craig’s, Andrew was the most technically accomplished guitar player amongst us.”

Eldritch was far from an instinctive artist. “He didn’t go for something that felt good right in the moment,” says Hussey. “Andrew would spend days and days on a guitar-line. I think that’s the academic side of him, that ordered part of his brain.” This natural aptitude for intense focus was speed-sharpened and the origin of much of the material created in the golden year.

The Sisters have a well-deserved reputation as a hard-living band but that does need qualifying. On “a sliding scale Craig and our driver Steve Watson were usually vying for top spot,” says Marx. Eldritch may have gone on to become one of the all-time Kings of Speed, but at this time “his consumption was a sort of ‘little and often’ approach,” adds Marx. “By and large there was a code of get the job done first – a discipline that came from Andrew and me.”

Marx took no drugs at all. “I could be relied upon to have my act together. In that sense I was something of an oddity in a rock band, as he was in his own way. Neither of us had much patience with people who got stoned.”

Although a night owl, Eldritch was the indoor variety. “Andrew was not someone who chose to venture out that much,” continues Marx. “Claire was much more the one for going out for the night. Because it was known we were open around the clock there was usually someone coming back from the pub or club with Claire, most typically Craig, Jez or Danny.”

This would have most likely been from one of the post punk safe havens in Leeds: The Faversham pub or one of two clubs – The Warehouse and Le Phonographique.

“As the band became more successful there were more people wanting to get in on the act and would turn up,” says Marx. “Andrew could be pretty nasty if he took a dislike to someone. God bless him, he did like an argument.”

7, Village Place was also the headquarters of a record label, The Sisters’ own Merciful Release. “I don’t think Merciful Release existed at Companies House,” says Adams. “It was just a logo. It was Andy’s invention.” With the exception of ‘Body Electric’ / ‘Adrenochrome’ in early 1982, MR put out all of The Sisters’ records.

Village Place was also subject to “regular visits from all those under or wishing to be under the MR umbrella,” remembers Marx. First were The Screaming Abdabs (later called The Flowers Of Evil) from Wakefield, although a release never happened. Next were The March Violets, who put out ‘Religious As Hell’ and ‘Grooving In Green’ on MR in August and November 1982.

Third, were Salvation, a group put together by Horigan. Their ‘Girlsoul’ / ‘Evelyn’ single was produced by Eldritch and came out on MR in October 1983. Horigan had played in The Sisters, one time – on synth – making, as Marx recalls, “white noise as a mad, surrogate Eno through a ramshackle version of ‘Silver Machine’” at an all day benefit gig in Tiffany’s in Leeds.

Merciful Release records were mastered by the legendary George Peckham (and so bear his imprimatur – “A Porky Prime Cut”) and had semi-decent distribution via Red Rhino in York, part of The Cartel. It was Eldritch who fixed the details of whatever the deal between MR and Rhino was.

The lounge of Village Place also doubled as a makeshift design studio. The artwork was also Eldritch’s remit. “There was most likely a Letraset catalogue or a few sheets of Caslon Antique font with the latest poster or artwork layout half-finished,” recalls Marx. “He had an eye for fine pens,” Horigan agrees.

As great as the live shows were, it was the records that most define The Sisters’ golden year.

‘Alice’ – atypically – was written very quickly by Eldritch. So rapidly that “I don’t remember ever hearing him messing about with the guitar lines,” says Marx. “It just arrived as a fait accompli. My memory is of him coming back from a stay with John Ashton (the guitarist in The Psychedelic Furs) in London with the song complete.”

“Andrew brought the demo in, pressed play on the cassette machine and it was like he’d found the turbo charge on the Sisters-mobile.”

‘Floorshow’, which formed a double A-side with ‘Alice’ in November 1982 was generated differently. In fact, the obviously Lemmy-like bass-line pre-dated The Sisters. Adams had written it for The Expelaires, one of his previous groups. Paul “Grape” Gregory, the singer in The Expelaires, laughs when he recalls that, “we told him it was shit.”

“’Floorshow’ was a track we demoed several times and never quite got it right,” says Marx. “I think Andrew wanted to accentuate what he saw as the rap/dancefloor aspects of the track; something akin to Talking Heads was even mentioned at one point. He wanted Craig to play what we mockingly called a honda-honda bass-line”, which was one that hopped back and forth between octaves the way many Theatre Of Hate/Spear Of Destiny tunes did. “Craig, as was often his way, told him to fuck right off.”

“The lyric shows Andrew’s fluency, as well as a sense of humour,” continues Marx. “It’s a barbed attack in the great snarling tradition of Dylan and The Stones, but it would sit equally well with a punk or post-punk figure like Howard Devoto or Richard Butler.” The irony – likely intentional – was that a song which binds up dancefloor hedonism with systemic cultural decay, itself became a floor-filler at alternative clubs.

“The finished result seems to exemplify everyone doing what they did best and that includes the drums”, Marx himself, who had “decided to play anything but the actual riff”, and John Ashton’s production.

The quality and popularity of the ‘Alice’ / ‘Floorshow’ single made a huge impact on Eldritch too. “The success of ‘Alice’ made me have another re-think. My attitude did change. I thought this is a goer, this has got legs,” he told tQ last year.

Originally Eldritich “didn’t foresee a career as musician. One of the great things about punk was that it allowed people to express themselves without the pressure of careerism.” In their earliest incarnations, The Sisters shared this outlook with other Leeds bands like The Mekons, Delta 5 and The Three Johns “who had no careerism in them whatsoever.”

After ‘Alice’, the possibility of a sustained future within music, whether as rock star, label boss, producer or Svengali – or all four – opened up.

Eldritch had dropped out of two universities. Without a degree, the most likely career path for a man of his talents – the diplomatic service – was closed. In fact, with his very specific skill-set – languages, programming and cryptic puzzles – Eldritch had already missed his calling by a generation: cracking coded U-boat messages at Bletchley Park.

All of that great run of singles in 1982 and 1983 were recorded at KG Music Studios in Bridlington. This was a second home to The Sisters and it was here that Eldritch learned “to work a desk … and bend some needles.”

The first visit after the ‘Alice’ sessions yielded the ‘Anaconda’ single. Eldritch wrote the words – about a heroin addict and some of his least opaque – Marx the music. As usual, this had been prepped at Village Place. By Sisters’ standards, Marx had gone ultra-sophisticated. “I borrowed Danny Horigan’s reel-to-reel. It was the first time I remember using any home multi-tracking gear,” he recalls. Prior to that he didn’t layer anything up “other than in the crudest fashion” by playing along to a cassette and recording the results on another cassette player.

“As for the actual recording I was disappointed that we weren’t able to get the most out of the track,” says Marx. “There was an element of it being a bit of a stop-gap single.” Adams agrees. “It was Andy’s first attempt as producer and it sounds weird.”

Eldritch was out of his depth, even in a small 8-track studio like KG. There was nothing unusual in this. Eldritch has spent huge portions of his time in The Sisters deliberately over-reaching himself. Sometimes the results have been utter car crashes, mostly they have been glorious. Even some of the pile-ups have been magnificent. ‘Anaconda’ is much closer to The Sisters’ best work than their worst.

The recorded version of ‘Anaconda’ still sounded like The Sisters, albeit, The Sisters sometimes sliding towards abrasive, mutant funk, like The Stooges’ ‘Scene of the Crime’. The star of the piece was Marx’s staccato, scratchy lead riff played high up the fretboard.

The B-side, ‘Phantom’, was straight-up sensational though, a quasi-dub of ‘Floorshow’, ‘Rock And Roll Part 2’ to ‘Floorshow’s’ ‘Rock And Roll Part 1’.

It actually dated back to improvisations during the ‘Alice’ / ‘Floorshow’ sessions. Marx had borrowed a vintage Burns guitar from his friend Steve Barber, who was known to everyone as “Laughing Boy” because of the effect cheap Polish spirit had upon him. Marx had never used a tremolo arm before and tested it out at KG with the ‘Floorshow’ drum pattern. “Everyone was leaping up and down in the control room saying it sounded great and not to forget what I’d been playing.”

Back in Village Place after the ‘Alice’ / ‘Floorshow’ sessions Marx worked up a full instrumental. “Once I’d given Andrew some indication of how much I’d got, he modified the drum track.”

When The Sisters were due to return to KG, Marx “couldn’t get the Burns guitar. Jon Langford (of The Mekons and The Three Johns) came to the rescue but his guitar had the tremolo arm snapped off. To operate the action you had to wedge a fork in and use that as the lever. Bands of similar status (as us) that we’d run into doubtless all had these pristine Gretsch guitars. I love that jumble sale aspect of what we did.”

Shortly after Anaconda came out in March 1983, The Sisters put out Alice as an EP including ‘Floorshow’, ‘Phantom’ and their version of The Stooges’ ‘1969’. This was the format that had been released in the USA that was finding its way back to the UK, with fans paying extortionate prices to hear ‘1969’, which had been recorded the previous year with Ashton.

Sound and method changed again for the next release, for many, the early Sisters’ masterpiece: The Reptile House EP.

“I would say that’s my favourite Sisters’ stuff ever,” declares Adams.

Since the recording of ‘Anaconda’, The Sisters had acquired a Portastudio, “which allowed Andrew to exercise a little more control over how his songs turned out,” says Marx. “’Fix’ definitely grew out of him layering up a track on his own. The semi-whispering and falsetto vocals came about because he was trying not to make too much noise while recording them at Village Place on the night-shift.”

At KG, the praxis begun during ‘Anaconda’ continued. As a producer Eldritch was an inveterate experimenter and fiddler, often because he simply didn’t know what the equipment did. Whether this was arrogance or bravery, he continued to learn, at a rapid pace. “His production on The Reptile House was fantastic,” adds Marx, “very playful in lots of ways for such a seemingly serious collection of songs.”

The best songs, especially lyrically, are on the second side, a vortex of tenderness and horror: “romance and assassination”, “love” and “genocide”, “a shiny love song and a quick incision”, “kissing” and “carnage”.

Marx believes that ‘Valentine’ in particular contains some of Eldritch’s best lines. He quotes:

“A people fed on famine

A people on their knees

A people eat each other

A people stand in line

Waiting for another war and

Waiting for my Valentine.”

“Brilliant.”

To do some of his finest work, Eldritch sometimes had to sacrifice looking cool. “In the studio he insisted on having the backing track to it (‘Valentine’) ever louder in his headphones,” says Marx. “Kenny Giles told him the sound from the cans was spilling into the vocal mic. Andrew did his vocals wearing a bobble hat to help combat the sound bleeding through: the supposed Prince of Darkness looking like a cross between Mike Nesmith of The Monkees and Benny from the soap opera Crossroads.”

The whole EP was richly allusive, to – amongst others – the MC5 (the bass riff in ‘Fix’ is ‘I Want You Right Now’ slowed down), T.S. Eliot (‘Valentine’ utilizes fragments of ‘Sweeney Erect’) and Apocalypse Now! (the cover is a collage taken from a photograph in the December 1968 issue of National Geographic entitled "Mekong: River of Terror and Hope”).

The Reptile House was a journey up river into the dark heart of the body politic – sophisticated, witty, heavy.

The EP “felt substantial,” remembers Marx. “Andrew was justifiably proud of it as an artistic statement” and he continued to labour over it long after recording. Eldritch painstakingly made the lyric sheet for the EP, each letter needing individually dry-rubbing from a Letraset sheet.

The Sisters of Mercy played in Europe for the first time the month after The Reptile House came out. They headlined the final night of Parkingang, a well-funded alternative arts and music festival in Ancona in very late July 1983.

“It had the feel of a holiday,” recalls Marx “because it was just one gig with a few days stay. The gig in a central plaza was awful, but the trip was memorable. Ben took his expensive camera, which I managed to drop in the sea. I then trod on several sea urchins and spent the next few days almost crippled, walking around in my brothel creepers with the skin around the spines getting more and more infected.”

Band and crew were accommodated in decent apartments in Ancona and the festival organisers spent a lot of time “running around on scooters looking after us,” recalls Horigan, but were nonplussed when asked to procure some speed. “We might as well as asked them for heroin.”

A few days later, The Sisters played out of doors, in another square, in another European city.

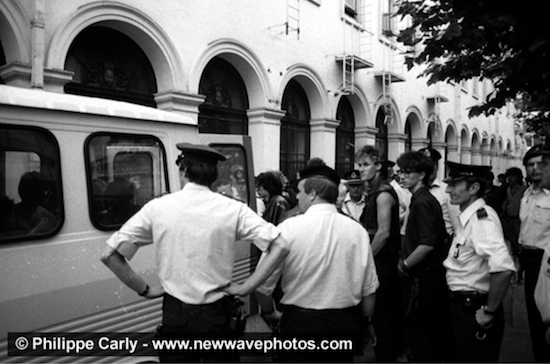

The Mallemunt festival in Brussels degenerated into one of the most notorious episodes in early Sisters’ history.

Much of The Sisters’ following took a vodka-soaked night train though The Alps, arriving in Brussels before the band, where they managed “to locate a bar next to a tattoo parlour which served incredibly strong beer,” says Marx. “For whatever reason, some locals got involved in a couple of messy scraps with our lot that boiled over into the day of the gig.”

The gig itself had problems, other than being in broad daylight and in a downtown shopping district. “We had a power spike just before we started and the drum machine wiped,” remembers Adams. “So Ben had to get the master book out and program the drums from scratch.”

“Ben kept messing up with starting the drums and got us all wound up,” adds Marx. The Doktor blurted out repeatedly during the very solemn and lengthy introduction in Flemish the band were being given.

There were further technical issues. Eldritch immediately complained about the sound mix and then Adams’ only pedal broke. “The pedal’s fucked. That’s Belgian for ‘fucked’ by the way,” observed Eldritch. “I don’t think the state of my foot was helping either,” adds Marx. Eldritch, who doesn’t have the reputation as a Francophile introduced ‘Emma’ in perfect, English-accented French: ‘Il y a quelqu’un ici qui se souvient de Hot Chocolate?’ afterwards summing up his own and the band’s performance with “Errol Brown, eat your heart out.”

The gig then descended into a bad parody of Altamont.

As The Sisters began ‘Gimme Shelter’, police vans entered the square. Several of the travelling Yorkshire contingent had climbed into a fountain and a fight had broken out. This intervention was witnessed by more bemused late shoppers, than it was by rock fans.

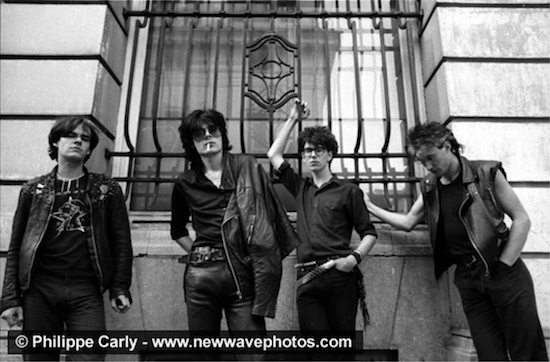

The police were still looking for troublemakers after the gig, when they found The Sisters in the middle of a photo-shoot in a side-street. They and their crew were rounded up. “The photographs with me, Danny and Jez grinning as we are being herded into the meat-wagon took pride of place in my house for many years,” says Marx.

The Sisters, Horigan and Webb were let out of the van without charge a short while later.

As this Brussels show had demonstrated, The Doktor did not just impact the sound of The Sisters, he also shaped the dynamic of shows and the relationships within the band.

“Ben took over those drum minder duties but he didn’t cope well with the pressure,” Marx believes. “By then we were using a more sophisticated machine. He regularly made a mess of things with the obvious consequence that Andrew tore into him and Ben became ever more anxious.”

Before using their actual drum machine on stage “we ran it from 4-track cassettes, so I had to change the cassette every song,” says Adams. “I had to check the master book and mix the four channels before we could start a song” which is why there were often such delays between them.

The longeurs necessitated by the drums, created dead time for Eldritch to fill. “He’d just stand there smoking and insulting people,” is how Adams puts it. Eldritch’s baiting of the crowd, throwing out non-sequiturs and rhetorical questions and engaging in an internal dialogue with himself – out loud – became integral parts of Sisters shows. Marx had a few short instrumentals he could deploy to fill time: ‘Ghost Riders In The Sky’, the main theme from Lawrence Of Arabia, ‘Hava Nagila’ and “if the mood took me”, ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’, “one of the first things I learnt to play.”

Although they had probably gone too far in Brussels, “the importance of Jez and Danny to the band shouldn’t be underestimated,” states Marx. “People may assume the chemistry is between the members of the group but in actual fact it’s that wider team.”

“Jez and Danny were a great double-act and kept everything buoyant,” continues Marx. Horigan believes that “Eldritch was very aware of how each gig had to be special and a big deal. He knew the camaraderie was important and he was part of that.”

As well as roadying, Webb and Horigan were the cheerleaders. “As soon as everything was set up, they’d both go into the crowd and get everybody dancing,” says Adams. “You’d see Jez’s blonde head bobbing about.”

Ancona and Brussels were just one-off dates. Later in August 1983, The Sisters began their Trans-Europe Excess tour, their first proper tour of Europe. The pun could be on the title of the Kraftwerk album, but with Eldritch’s background it could just as easily have been the Alain Robbe-Grillet film.

It took them to some of northern Europe’s most legendary venues: the Vera in Groningen, the Paradiso in Amsterdam, the Effenaar in Eindhoven; and the Loft in Berlin.

Before they went, they had recorded a new single: ‘Temple Of Love’.

“Andrew was more concerned than I was about the exact nature of that release,” says Marx. “We all knew it needed to be a more obvious single, I just thought it needed to be catchy and direct, he believed it had to work at a very high tempo. There we disagreed and never really saw eye-to-eye again until he’d finished ‘Temple Of Love’.”

“We booked the studio with just a skeletal version of how it might be and Andrew’s determination to make it work,” says Marx. “For the bulk of those sessions Craig and I let him get on with it and play with his gadgets.”

This time The Sisters were in Strawberry Studios in Stockport – “10cc’s studio, very posh,” as Adams puts it. Neil Sedaka and Joy Division had also recorded there. Other evidence that The Sisters were moving up in the world was that ‘we had a boarding house in Stockport and we’d get a cab to the studio,” recalls Adams. At KG, they had slept on the studio floor.

“We spent longer on ‘Temple of Love’ than envisaged and moved across to the lesser of their two studios,” recalls Marx. “There were quite long periods of experimentation with Andrew chaining up noise gates and delays to produce sequenced bass or whatever metronomic effect he thought was going to bring his flimsy idea to life.”

Marx thought Eldritch was wasting his time. “When he came back in the early hours after finishing the mix on his own and woke me up to knock it out on the ghetto-blaster, any such thoughts were obliterated. Hearing the chorus kick in for the first time is one of the landmark moments of my life. Boy, did he gloat!”

The B-side was ‘Heartland’, one of The Sisters’ songs that Marx contributed the most to. He wrote the music and “a draft lyric for it. Andrew threw the chorus lyric out and paraphrased the verse I’d written before expanding upon the whole thing. Even so, there was a sense that I’d pointed the way melodically and lyrically.”

‘Gimme Shelter’ completed the 12” single. Marx thinks that this “is probably as good as Andrew ever got us to sound on record. It is one of the tracks which reminds me most of Andrew’s Bowie fetish. The way the multi-tracked vocals sound is very reminiscent of the Diamond Dogs album for me – no bad thing.”

When they left Strawberry the final recordings of their golden year were complete. The Sisters of Mercy had very little material left over.

“There was never any danger of being labelled prolific,” admits Marx.

Some songs would remain shelved: ‘Good Things’ which the band had played at their first ever concert and recorded with John Ashton at KG; ‘Burn It Down’ (some of the drums and lyrical themes would reappear as ‘Burn’ on The Reptile House) and ‘Driver’, some of the lyrics of which got shunted over into Heartland. “I really liked ‘Driver’ or parts of it at least,” says Marx, “but Andrew never made any real claim for it to be considered.” Marx had also written the tune which would eventually become ‘First And Last And Always’.

“The track that didn’t surface which could have easily had a seat at the top-table was called ‘Dead And American’. I really loved it and nagged the hell out of Andrew to finish it. The problem was that it was the nearest we ever came to doing something that you could say had a groove. Suddenly all these two-bob Indie Funk bands came through. We must have decided to distance ourselves from that trend. The main chanted chorus line was this staccato, ‘…two wings meet the mountain I’m dead and American 21 …’”

With ‘Temple Of Love’ certain to become their biggest hit to date, and with their golden year drawing to a close, The Sisters of Mercy paid their first visit to the USA.

The Sisters had an audience waiting for them in The USA. American Indie music fans read the British music weeklies and they could buy Sisters’ records because they were distributed by Braineater from New York City, which in turn was owned by the larger and influential Dutch East India Trading label, also from New York.

The Sisters would also have been well known to East Coast bookers like Warren Scott in Boston and Ruth Polsky in New York. Therefore, it was natural that The Sisters played The Channel and Danceteria in those cities. They played the latter twice in three days. The most powerful advocate The Sisters had at the time was the Englishman Howard Thompson who was in charge of A&R at Elektra and was an admirer of the band.

Alan Vega also visited the band backstage at Danceteria. “He was wildly funny and could quickly take over a room,” says Marx “but he was drawn to Andrew rather than the band.” Vega was a huge influence on Eldritch: the cheap drum machine, the vocal style – especially the yelping and screaming – and a stage persona that had menace and toughness, but was also very camp.

In New York, it was Polsky who was The Sisters’ most important conduit.

“Ruth was plugged into the scene; you could go places with her and bypass some of the nonsense,” recalls Marx. “She was used to dealing with English bands and seemed to like our ‘Northern thing’. She played ‘Reel Around The Fountain’ by The Smiths for me in her apartment.” Marx remains unsure whether this amounted to flirting from an Anglophile music fan like Polsky.

Adams has his own vivid memories. “I remember being sat with Ruth and Andy in Danceteria and she asked, ‘Do you want a line of coke?’ And we were like, ‘Have you got any speed?’ We were cheap, man.”

Adams became good friends with Polsky and, according to Howard Thompson’s Northfork Sound blog, “one of her favourite people was Andrew Eldritch.” Polsky loved photography and Eldritch used a photo she took of the band in Detroit the following year as part of the artwork for First And Last And Always.

“I suspect we drove her mad,” continues Marx, “especially when we hooked up with a friend of a friend who lived out there, the aptly named Brian Brain Damage. Craig and I weren’t overly concerned with the dangers inherent in running wild in a city like that. She was all too aware.”

In New York, The Sisters stayed at The Iroquois Hotel – the first of many times. “I used to have to share with Andy, which was a pain,” recalls Adams. “I don’t quite know how that happened. He used to drive me insane.”

In fact the more they toured, the more Adams was infuriated by Eldritch, but in September 1983 – and for a good while yet – Adams was having a great time being in The Sisters and was not totally wound up by “the little, niggling, stupid things.” He was anaesthetised to what he found the irritating aspects of Eldritch’s personality. “He was always on speed but I was speeding and a bit drunk and a bit stoned, so I think I could deal with it. A lot of the time I was really out of it.”

For their part, Marx and Eldritch’s relationship would later degenerate to the point where they would spend much of 1984 and 1985 not talking to each other. “It got worse over time to the point where they would use Claire, Craig, and myself to pass messages back and forth,” says Hussey. Yet, in the late summer of 1983, although there was evident friction, their association was still intact.

Ben Gunn’s time in The Sisters was coming to an end however.

He absolutely hated the American tour.

“Ben’s reaction to the US was markedly different from everyone else’s,” believes Marx. “He got worked up about the poverty we saw on our travels. We’d asked to go ‘sight-seeing’ through some of the boroughs and it all got a bit ‘cheap holidays in other people’s misery’ for Ben.”

Also, being in a band and under 21 in the USA could be ignominious. Not only could Gunn not drink in the clubs, he could barely get through the door. Adams recalls that “Ben had to sit in the van and be pulled out just before we went on and had to go straight back out again after the show had finished.”

Marx remembers that the end point of Gunn’s time in The Sisters was triggered when “Ben delivered an ultimatum demanding more of a role within the band.”

“We didn’t really appreciate being presented with ultimatums.”

The second of the Danceteria shows was Ben Gunn’s last gig in The Sisters of Mercy.

“Ben’s leaving was really just another in a line of similar departures, so nothing we felt threatened by,” explains Marx.

The Sisters were in no rush to find a replacement, but Gunn’s spot in the band remained vacant for less than a month.

Unlike all the other previous fourth members – Tom Ashton, Dave Humphrey, Jon Langford – Ben Gunn’s replacement was not found in the Leeds post punk scene. This time Liverpool filled the gap.

The matchmaker between The Sisters and Wayne Hussey was Annie Roseberry, who did A&R for CBS. She knew that Hussey had recently quit Dead Or Alive, who were then on Epic, a part of CBS. CBS also wanted to sign The Sisters, so she recommended Hussey to Eldritch.

“By that time in Dead Or Alive, all the guitar lines I was coming up with were being put in a sequencer,” Hussey remembers. “In my own mind, I was a guitar player and it would have been good to be in a band where the guitar was the principal instrument.”

Even so, The Sisters were not really on Hussey’s radar. “’Alice’ and ‘Floorshow’, I recognised from club nights at Planet X in Liverpool”, but the rest of The Sisters material was unknown to him. “I was more of a pop boy.”

From The Sisters’ perspective, Marx remembers “getting this Dead Or Alive single sent to us. I suspect it was just to show us roughly what he looked like on the cover.” Marx’s overall impression was “Robert Smith light” which was neither ideal, nor that off-putting.

Despite his mild misgivings, Hussey took the bait and went to Leeds to meet The Sisters.

He was driven to Village Place by his friend Kenny Dawick, who was a DJ at Planet X. Hussey’s immediate reaction was that he was at the wrong address because Number 7 “was completely blacked out.”

The sitting room was, as ever, dimly lit. “Andrew was in there curled up on a chair in the corner stroking a cat.”

By Autumn 1983, when Hussey first met The Sisters, Andy Taylor had, to all intents and purpose, metamorphosed into Andrew Eldritch.

“I only ever knew Andrew Eldritch,” states Hussey. “By the time I joined the group he was the same person off stage as he was on. I never met Andy Taylor. The persona was already all in place.”

Tea was drunk. Cigarettes were smoked. Amphetamine was taken.

Adams, unlike Marx, “didn’t know what Wayne looked liked” so when he arrived – while Hussey was upstairs – he spent several minutes in the murky living room quizzing Dawick about his experience as a guitar player and his suitability for The Sisters.

When Hussey did return to the living room and was correctly identified to Adams, “we got on instantly,” Adams recalls. “We left Andrew and Mark and went to the pub. Apparently, I asked Wayne to lend me a fiver.” A long-lasting partnership was born.

Before leaving Village Place, Hussey had been given “a pile of Sisters’ records, including ‘Temple Of Love’, which was about to come out.”

Hussey liked ‘Temple Of Love’, but it was ‘Gimme Shelter’, that hooked him. As for the rest of The Sisters’ songs, “I wasn’t blown away to be honest,” he admits. Nevertheless, he quickly made his mind up that he wanted to join. The prospect of regular touring was also very attractive to Hussey.

Eldritch phoned and offered Hussey the job the next day.

The Sisters had chosen their new guitarist from a shortlist of one, although Marx has a tentative memory that “there may have been a discussion between Andrew and me about John Perry of The Only Ones. Andrew was keen to approach him but he suspected I wouldn’t buy into it.”

An audition did not form any part of Wayne Hussey’s recruitment.

“There’s no reason we would have needed to hear him play live,” explains Marx. “We were not a muso band or in need of any great technical proficiency. The fact he’d worked with more than one signed band suggested he could play anything we threw his way.”

“As soon as Wayne moved over to Leeds, we went out every night together,” recalls Adams. “We were like the evil children. We were on a mission of destruction – of stuff and ourselves,” is how Adams describes those weeks and the years that followed.

A key shift in the band had been inaugurated. “Wayne and I both drank and hung out. Andy and Mark did not come out very often. Mark didn’t even drink tea or coffee. He drank water or orange juice,” Adams explains. Previously, there had been one rock’n’roll animal in The Sisters, now there were two.

“When ‘Temple of Love’ came out and went to Number 1 in the Indie Charts, I was enjoying the celebrity status and getting that much attention without really doing anything,” says Hussey. “It became clear how revered The Sisters were, when you went out to The Fav, The Warehouse and The Phono.”

Before even playing a note, Hussey brought other major changes to The Sisters. “He had lots and lots of equipment, guitars, acoustics, twelve strings, pedals – even more than one type of distortion pedal,” remembers Marx. “He had a ‘wardrobe’, all these Worlds End outfits he’d bought during his time in Dead Or Alive. It was like having a rich cousin you didn’t know about suddenly turning up on your doorstep.”

The Sisters had a trio of dates booked for October 1983, which they played as a three-piece without Hussey, who had been in the band for only a week. “The shows were actually great with the three of us,” remembers Marx. “I knew I was going to be more exposed as a guitarist but by then it wasn’t quite the problem it would have been in ’82.”

Stockholm was first and after that The Sisters had two dates in California. “The idea to carry on and do the few shows we’d got booked in the autumn may have been partly to do with whatever relationship was going on between Andrew and Patricia Morrison,” suggests Marx. Eldritch and Morrison had first met earlier in the year when she was playing bass in the Gun Club.

The Sisters certainly travelled cheaply to America. “We didn’t even have guitar cases,” says Adams. “You had a guitar in a plastic bag with your cable, fuzz box and your other cable. That’s how we landed in Los Angeles.”

That Eldritch was able “to hook up with” Morrison “was a source of some resentment for me and Craig,” states Marx. “He got to stay with her and hang-out with her circle in L.A. while we were holed up in a crappy single room in The Tropicana Motel, living on next to nothing for a week.”

The Los Angeles show was at the decrepit Alexandria Hotel, once luxurious now stranded in a part of the LA downtown abandoned to the homeless, the drug addicted and the criminal. “It was a no-go area,” remembers Adams.

“The promoter had put out folding seats,” he also recalls. “Well, that didn’t last long.” The fate of the chairs can be deduced from a bootleg recording. Before playing ‘Temple of Love’, Eldritch dryly informed the crowd, “I’m perfectly happy with the number of teeth I’ve got, thanks. One less would not be very good for me, so that’s the last chair, I’m going to accept up here.”

The show at the I-Beam in San Francisco was two days later, on Halloween.

“We had to judge a fancy dress competition after we finished the set,” Marx recalls. “There was a woman naked apart from three very small pieces of sticky tape and a great Jackie O complete with butcher’s shop brains all over her jacket. Andrew had to do his game-show host bit.”

Then, with the money saved on Gunn’s airfare, The Sisters went on holiday.

They hired a station wagon and went on a road trip that included Las Vegas, Death Valley and Nashville. John Hanti – their tour manager – had offered to do all the driving, but because their rental vehicle “was an automatic and had cruise-control, Andrew insisted on taking the wheel on the long straight roads, despite the fact he didn’t drive at the time.”

And with that The Sisters of Mercy’s first golden age was very nearly at an end.

If Eldritch had a masterplan, it had worked brilliantly.

If so, it contained a paradox. “Of course at the heart of this masterplan was the decision to invite two people along who had no interest or desire to be governed by anyone’s over-arching strategy,” says Marx “How’s that for planning? How should we interpret that?”

“Very quickly our limitations became the sound,” he continues. “My lack of musicianship and Craig’s bloody-mindedness forced us down particular roads in those first two years.”

“Those songs would never have been the same without that personnel,” believes Adams.

This of course includes Eldritch himself.

That he became a great lyricist is not hard to fathom, but how – and why – Andy Taylor, an introvert who disliked crowds and loud noises, was able to effect his transformation into Andrew Eldritch, one of rock’s greatest performers, remains an enigma.

Several imperial phases would lie ahead of him but the golden year was the work of a band that in January 1983 Eldritch described to Melody Maker as “ludicrously democratic”. This two-word phase gives a clear indication of the inevitable upcoming shifts in the power structure, but for a little while longer the fate of The Sisters was a collective responsibility.

In November 1983, The Sisters of Mercy – especially the core of Adams, Marx and Eldritch – were in peak condition. They had a Number 1 single in the Indie Charts, a talented, experienced and likeable guitarist installed in the troublesome fourth spot and major record labels sniffing around looking to do a deal.

The Sisters of Mercy then disappeared. Their golden year was now over. It would be another six months before they played live and another eight before they released a record.

They had gone into purdah to begin the process of making their first album.

Therefore, November 1983 also marks the beginning of the end of The Sisters of Mercy.

Their first end.

The pressure to write, record and promote the album killed the relationships between Marx, Eldritch and Adams, the original band.

In fact, it nearly killed Eldritch. Over the next two years, Eldritch went far, far up river. The journey he began as Willard (or even Conrad), he almost ended as Kurtz.

Yet, the album when it eventually arrived was deeply flawed. It was questionable whether it merited the human toll it took to create it.

The Sisters’ golden year was not so blighted; it was all bang, no whimper.

It contains one of the great runs of singles by any post-punk band and is the bedrock of The Sisters’ reputation and longevity.

It was an astonishing 12 months, even for those in the eye of the storm.

“I suppose the clearest memories I have of being aware of how special the band were becoming,” remembers Marx, “were on the occasions I left the stage early during the last number. I would sometimes run around to the back of the hall to stand and watch, having left my battered guitar feeding back while the other three carried on with ‘Sister Ray’ or whatever number it happened to be.”

“There was something about the way it looked, as well as how it sounded. The casual destruction brought to mind the footage you see of kids playing in the bombed out ruins of a city; a scene of devastation but the children treat it as if it’s completely natural, almost like they’ve been waiting for the buildings to topple all along.”

With thanks to Phil Verne of the Facebook Sisters Of Mercy 1980-1985 Group and Nikolas Vitus Lagartija of the I Was A Teenage Sisters Of Mercy Fan blog

Sisters Of Mercy play live at London’s Roundhouse on September 1 and 2