Little ever seems easy for Sinéad O’Connor. There she was back in spring 2012, enjoying the plaudits for her first album in five years, nestling in the UK Top 40 again after an absence of a good decade or so, when suddenly – or so it seemed – she was forced to call off an extensive European tour, one that was already underway. In her typically candid fashion, she made no secret as to why this had happened, publishing an open letter of explanation on her website. She’d been prescribed medicine that potentially worsened her bipolar disorder, she explained, and her manager had set up a punishing schedule for her about which she was “only consulted… approximately 8% of the time”. With her health worsening – and another suicide attempt only recently behind her – cancellation, she made it painfully clear, was the only option.

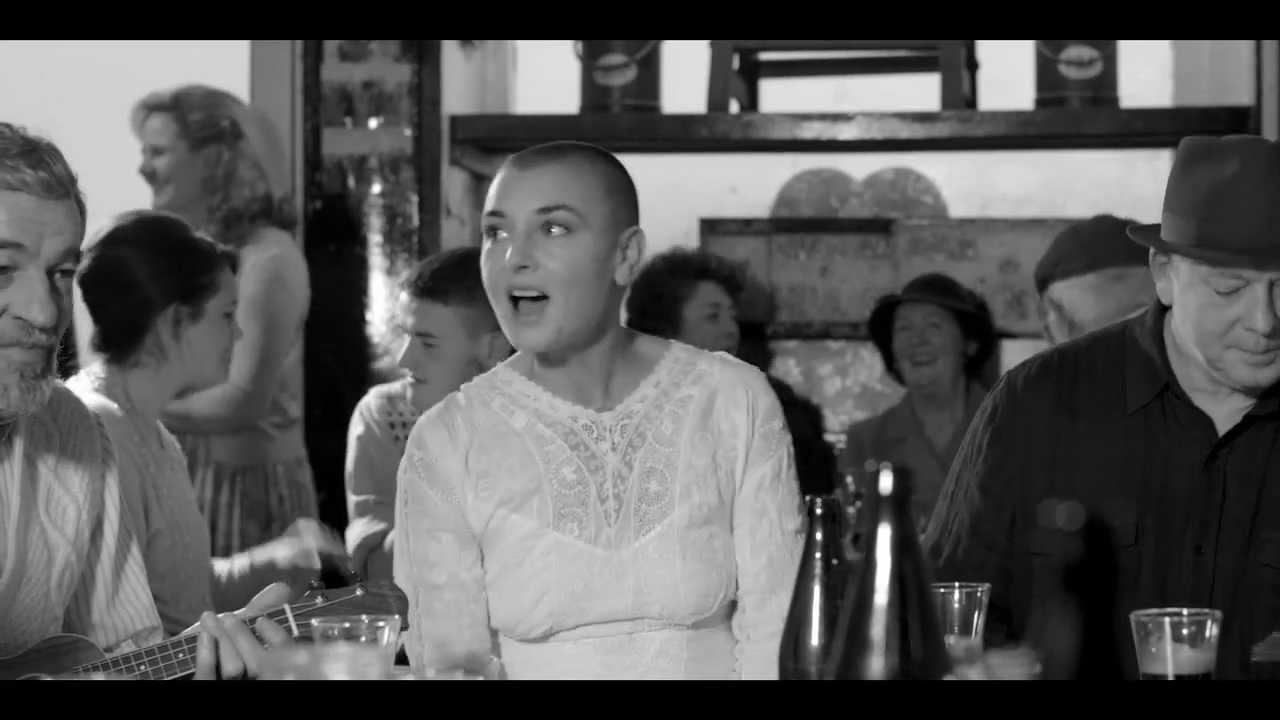

But she’s back now: fit, happy and healthy, she says. She’s been out on the road playing shows, has a new single out, and her regular, somewhat stream-of-consciousness tour diaries prove that her sense of humour hasn’t suffered one bit. (“Have shaved head this morning so am gorgeous. Did the legs too.. not that any man is ever coming near me… but if I should get hit by an elephant or something… I won’t be like wolf woman lying in the hospital.”)

She’s had a rough ride since the start, of course. Her life story reads like the script of a-rags-to-riches TV series, except that every time it looks like a happy ending is on the horizon she’s confronted by yet another drama. Ratings have gone up, ratings have gone down, but still she pulls in the viewers, and given the plot twists so far it’s not entirely surprising. She suffered physical abuse as a child at the hand of her mother – who died in a car accident in 1985 – and survived relocation to a Catholic correctional facility before selling two and a half million copies of her extraordinary debut album, 1987’s The Lion And The Cobra. But by 1990, the year of her biggest hit – a cover of Prince’s ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ – Frank Sinatra had threatened to “kick her ass” after she refused to countenance having the American national anthem performed before her shows.

She followed ‘Nothing Compares…’ seven million-selling parent album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, by tearing apart a picture of Pope John Paul II on American TV’s Saturday Night Live, an action which inspired Joe Pesci to do the same to a photo of her the following week and led to condemnation from an arguably rather hypocritical Madonna. (The act remains so controversial in American TV history that O’Connor’s picture was again torn up during an episode of 30 Rock last year.) In a further unexpected twist, given her ongoing outspoken views about the Catholic Church, only a few years later she was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest.

Additionally, she stated in 2000 that she’s a lesbian, though she later recanted and declared herself three quarters hetero, one quarter gay – “I lean a bit more towards the hairier blokes,” she added – and has been married four times. The last of these, she divulged, lasted only seventeen days, though she and her husband subsequently reunited a week later, O’Connor announcing the news with a tweet that claimed “yay!!! me husband is a big hairy cave man an came to claim me with his club : ) .”

She’s also pursued an unlikely musical path, releasing an album of jazz standards (1992’s Am I Not Your Girl), one of traditional Irish folk songs (2002’s Sean-Nós Nua) and another of roots reggae covers (2005’s Throw Down Your Arms). Her most recent release, however, sees her back in more traditional territory, and features some of her strongest material in years, not least the joyful jig of ‘4th And Vine’, the subdued fury of ‘Take Off Your Shoes’ (which finds her in as good a voice as she’s ever sounded) and the lyrically confrontational and musically vulnerable ‘V.I.P.’

On the eve of the release of a new single, ‘Old Lady’, the Irish singer took time to look back at her work and beliefs, as well as reiterating the crucial question that makes up the title of her ninth and latest album, How About I Be Me (And You Be You)?

I hope this doesn’t embarrass you, but the first thing I want to say is that your music has often been a great comfort to me, and I don’t think I’d be alone in saying that. But try as I might to talk only about your music, it seems to speak much about you as a person, especially in conjunction with the stories that have been written about things you’ve said and done. Do you think your work, and some of the difficulties you have faced, will all have been worthwhile so long as others hear your message?

Sinéad O’Connor: For people like yourself who are saying that my music was quite helpful to them, I think the thing is, you and I are the same, and the only reason my music exists is because I needed that comfort. And I gave myself comfort with that music, so the messages were to myself, actually. And then I think that translated because people could identify with it, because perhaps they were suffering similar things, or had been through similar things.

In particular, I was a survivor of very severe child abuse, for example. I was born and grew up in a time where there was no therapy. There was no place for people like me to put emotions, you know, so that music was the thing that saved us. And perhaps I was dealing with subjects that other people had not found a way to express their feelings about. And I think perhaps there was a message there that wasn’t intended for anyone but me, but because there were so many people like me it translated to some people, you know?

There was a guy in Ireland doing a piece, and he told me that his supervisor had told him to find out who the people I’m talking to are, and I couldn’t think who they were. But I said, "I bet if you could be bothered investigating my fans, you would probably find the majority of them had upbringings similar to mine, or are people who, for some reason, felt they had difficulty in being themselves. I think they’re interested in me because they see me as being myself, no matter what. And that’s encouraging, in the same way that, say, when I was young, I was very inspired by gay people when I came to England. Particularly, I was very inspired by the more queen-y, effeminate kind of gay people, guys that would go around dressed up in dresses. And I thought that was so brave, that these people could be themselves in a time when they were getting beaten up for being themselves. In my own country, a man couldn’t go down the road holding the hand of another man, so I found these people very inspiring, that they were being themselves and therefore I could be myself. And maybe that’s the audience that I have, if you like. There’s some message there, but it’s not necessarily intended.

And yet we all seem so cheerful when we go to see you play!

SO’C: Well, we are. That’s the thing. We are cheerful people, but we have to carry emotions and painful things that are sometimes difficult to find words for, and thank God we have music. And I think that’s why music is so popular, because all human beings have suffering as well as joy.

Do you think one reason that people think you’re a tough person is because of the shaven head?

SO’C: I think it started with that. I was perceived as a controversial, challenging woman because the haircut was perceived as something aggressive, which it really wasn’t. I think the haircut was one reason, and the boots of course, and then there was the fact that I was Irish and therefore mouthy, and that I don’t have a filter between thinking something and saying it. Someone described it very nicely writing an article on the twentieth anniversary of ripping up the Pope’s picture, that all the stars in showbiz were very frightened of me because – it’s a great way of putting it – an artist without a sense of self-preservation is a very dangerous thing. And I think that’s true. I wasn’t in the business for any other reason than to express myself. I didn’t give a shit about making money, or getting my records played, or having a good name, or have people talk nicely about you.

It hurt me that there was such a lot of shit dumped. But at the same time I wasn’t going to let it stop me being myself. But that was challenging, because, without meaning to, you’re accidentally holding up to people how much they’re cock-sucking. I didn’t mean to do that. I was just being me. But that pushed a lot of buttons for people, you know?

Do you think this latest record defines you better than any you’ve done, hence its title?

SO’C: Erm, possibly. Though I think you could possibly include the first and second record. In some sense you have to say that all of a person’s records would, but it’s the most well thought out and emotionally very mature. That’s not to discredit the others, because what was good about the others was that I was young, and I was very angry writing them at the age of fifteen and sixteen.

You mentioned self-preservation earlier, but you don’t seem to exercise a great deal of self-censorship. Is that a fair comment?

SO’C: I think that’s what the music is for. The thing is I always joke, but I’m not joking when I say that the music business was created for people who weren’t quite criminal enough to go to jail, and weren’t quite mental enough that they’re nut-heads, but at the same time weren’t able to function within a ‘normal’ society, so that they had to create the music business for us so that we could contribute usefully. And I’ve forgotten your question. For some reason I feel like that’s a logical answer.

It was about self-censorship.

SO’C: Yeah, you’ve got to be yourself, that’s the thing exactly. That’s what music is. It’s a place where you can really 100% be yourself. And that’s what I learned from artists like John Lennon and the Sex Pistols and the whole punk era. Brian May did a brilliant interview for The History Of Rock & Roll. He said that the thing is, when you get into rock & roll it’s because you’re a rebel and you want control of your own life. The irony is that the more successful you become, the less control you have, because everyone wants a piece of you. And that is the truth. And so when somebody like me comes along and starts kicking against all of that, it causes trouble for a whole lot of other people who are trying to make a living out of you.

Do you feel you were forced to compromise a lot in your career?

SO’C: No, but what I do feel is that the abuse that I got, I think 90% of it was because I was not seen as a conformist/cocksucker. I wasn’t fitting into the behaviour and cocksuck-ery that a pop star was supposed to fit into. It was really weird that suddenly I was a pop star, because it’s not my nature, and then because I had this number one record I was expected to behave like a pop star i.e. be a cocksucker. "Don’t cause trouble, don’t put your head above the parapet, don’t challenge anything, agree with everybody, smile nicely, be a good girl." I wasn’t trying consciously not to do that, but I think that it upset everyone because a lot of people around me had a vested interest in me being what they wanted me to be rather than anything I wanted to be. And I was too young to have even decided what I wanted to be. I just wanted to make records and sing. I wasn’t really thinking any further than that. Really I wanted to stay alive!

Did you imagine you’d be doing this twenty five years after The Lion & The Cobra came out?

SO’C: Yeah, and I’ll still be doing it when I’m 94. Definitely.

I saw you play a day or two before you took time off last year because you were sick, and I didn’t notice any signs at all that you were struggling. Given that you tweeted soon afterwards that you were "Asking about jobs as music biz is very bad for Sinéad. Any one have a job for a very clever woman with massive heart and courage, who adores people and has to escape music business as is very bad for her?", I’m wondering what’s brought you back to wanting to perform live again?

SO’C: I love performing live, and always have, and the only reason I ever make records is so that I can perform live, and that’s what I have in mind when I’m writing songs. That’s my number one love. It’s just that I wasn’t well then, and things had been scheduled in a manner that was impossible for me to manage, and there wasn’t time for me to get well. But it’s interesting, because you said to me, did I ever imagine I’d be doing this, but I actually feel like I’m just beginning. I actually feel like I’m at spot number one now, starting, if you like; to me it’s all been practice and training up to this point for the career that I intend to have, which is based on live work. And I think that’s going quite well, and I’m managing to build a good live reputation, and everyone knows that if they go to one of my shows they’re going to get 1000% off me, whether I’m dying or not. But that gig you saw I’m sure was a good gig, but if you had any idea how sick I was you’d be astonished I was able to do such a good gig. So you can imagine the kind of gig I can do when I’m well!

I want to talk about some of the songs on the recent album. There’s empathy on things like ‘Reason For Me’, but it’s not judgemental, and it’s not patronising either. How real are these songs?

SO’C: Yeah, well, really that’s based on a kind of conglomerate of people I’ve met over the years, and also on aspects of myself, I suppose. But that’s I suppose what I mean when I say it’s a mature record. There are some romantic songs and then there are what I call character songs like ‘Reason With Me’ or ‘Back Where You Belong’ or ‘Take Off Your Shoes’, where there’s actually another character, if you like. But in all of those characters, obviously, like any other actor, there are aspects of my own personality, I suppose.

Do you ever worry about patronising people when you discuss these more difficult issues?

SO’C: How do you mean?

Well, when writing a song about a drug addict (‘Reason With Me’), it might be very easy to intend to come across as sympathetic, but actually end up appearing high and mighty, as it you’re saying, ‘Actually this is the way you should be behaving…’

SO’C: No, because I think within that song that’s just a character. It’s a very introspective song. It’s a character really risking coming and telling the truth to you of whom he is, and saying, ‘I stole all your shit, and can you help me out?’ And I like that about it. It’s not judgemental of anybody on either side, and the character has great faith in the person that he’s stolen these things from. He believes that this very person can help him out. There’s something very hopeful about the song, too, that the person is at a particular point in their life where they’re actually feeling an awful lot of hope. And often when you hear songs about drugs, there’s hopelessness in it, and this character is very much on his knees, but particularly he’s appealing to the very person that he’s wounded, you know? And I think there’s something very nice about that. I like that, that he imagines that this person could love him back. It’s quite an amazing thing…

In contrast, on ‘4th & Vine’ and ‘VIP’, for instance, there’s a lot of humour. Do you think people overlook that in your work?

SO’C: I think you have to see me live to get it. It’s a bit like when you send someone a text: it’s flat reading, so it can come across without the emotions or the humour. It can sometimes be a bit the same with records, that you’d have to have see the person singing it live with a smirk on their face to realise that it’s funny, you know?

Am I being dirty-minded when I think the “buggy ride” in ‘4th and Vine’ is an innuendo? (‘So warm inside / When he takes me for a buggy ride.’)

SO’C: No, no, it is an innuendo, of course, directly stolen from Bessie Smith, and it’s a song called ‘When You Take Me For A Buggy Ride’, and it’s all about sex, obviously, yeah.

I just thought I was being a pervert.

SO’C: No, no, you must check the Bessie Smith song it’s ripped off from. It’s a beautiful song from 1910, 1920 kind of thing. A bunch of people did it, but she did the definitive version. It’s a very funny song…

You covered John Grant’s ‘Queen Of Denmark’ very soon after the original was released. Did it make you nervous that people would compare the two?

SO’C: No! No, I never even thought about it, to be honest. I just immediately identified with the song and loved it. John’s one of my best friends on earth now. I’ve done the backing vocals on his new album. We joke that we’re the male and female versions of each other. John is a genius of humour: he can take it to a very emotional, painful place, and then a moment later just be so funny. And that’s what I like about that song.

No, I wasn’t really worried. I think I might be worried if I was a man, but being a woman made it a little bit easier. A man putting it out might have run the risk of what you’re talking of, but John’s new album has so many songs on it that all the women singers are going to be bitch slapping each other to get at. He’s got one song on it called ‘It Doesn’t Matter To Him’ that – I’m telling you! – every woman on earth is going to be beating each other up to get. He writes great love songs from a man’s perspective to a man, but for women to sing them is incredible. Wait ‘til you hear the new album. You’re gonna drop dead. It’s incredible.

I assume he’s a fan of your cover, then?

SO’C: Oh, yeah, very much so. Although apparently I got one lyric wrong somewhere…

On ‘Take Off Your Shoes’ you describe yourself as ‘the Holy Spirit with an AK rifle on a train on the way to the Vatican’.

SO’C: Well, it’s not myself. It’s a character, in the same way as ‘Back Where You Belong’ is a character of a dead father talking to his son, and ‘Reason With Me’ is a junkie talking. The character in ‘Take Off Your Shoes’ is supposed to be the Holy Spirit. It’s not me; it’s the Holy Spirit.

How to you balance your disdain for those who claim to represent God and your own belief in a God for whom they claim to speak?

SO’C: Well, I believe in what I prefer to call the Holy Spirit, because I don’t know what to call it, but I don’t think it really matters if you call it Fred or Davey. I don’t just believe in it, but I know of it. But I don’t believe in proselytising on either side. What I don’t like is being misrepresented. Also, it concerns me that anybody running a church has so little belief in God that they could stand in the presence of the Holy Spirit and lie about such important things as the rape of little boys or little girls. It concerns me that the church is being run by people who don’t actually believe that God is watching, do you know what I mean? I think we deserve, and I think the Holy Spirit deserves, churches run by people who actually respect it.

It seems to me that the two themes that drive your lyrics the most are injustice and hypocrisy. Do you think that’s true? Are these closest to your heart?

SO’C: Yeah, there are some running themes. I’ve always been a bit of a God person, a spiritualized person, so there’s that theme running all the way through. And yeah, I suppose there’s a concern with spiritual hypocrisy, particularly. I don’t get involved in politics. I don’t give a shit about politics. I suppose where I’ve been concerned about hypocrisy it would be of a spiritual nature, as in ‘Take Off Your Shoes’ or ‘VIP’.

Before I finish, I have to say that I think four of the finest, most frank lines I’ve ever heard sung are ‘Thank you for breaking my heart/ Thank you for tearing me apart/ Now I’ve a strong, strong heart/ Thank you for breaking my heart…” (from 1994’s ‘Thank You For Hearing Me’.) I think it’s my turn now to thank you.

SO’C: Well, you know where I got that? Doctors will tell you that when you break a bone, when it mends it’s actually stronger than it ever was in the first place. We all have a million lives within the one life, and we all die a million times within that life, and each death gives us life, if you like. And though those deaths are painful to go through, sometimes you’re stripped bare of everything in life, and that’s a great gift, actually, because you end up with just the truth, whatever the truth happens to be.

I always say to my children, ‘Look, you’re only here for one reason, and that’s to be you. It doesn’t really matter what me or your Dad or anyone else thinks: you’re here to be you.’ If you come into the world with you, and you leave with you, and just you, then that’s great. That may be a bit of suffering, but that’s a great thing. That’s the object of the thing.

Sinead O’Connor headlines Glastonbury’s Acoustic Stage on June 28. ‘Old Lady’ is out now on One Little Indian Records