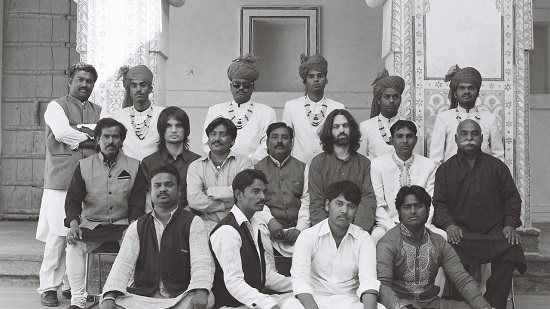

For three weeks in February this year, Jodhpur’s towering 15th century Mehrangarh fort was converted into a kind of spiritual oasis, from which Junun – "mania", "madness", "insanity" – surfaced. Shye Ben Tzur, the Israeli singer, guitarist, flautist, and composer, has, for over 15 years, been creating music in India, and Junun is a new double album, an expression of euphoria and devotion, that sees him fronting a collaboration with Radiohead’s guitar player Jonny Greenwood and 19 Rajasthani folk musicians (Rajasthan Express), with Nigel Godrich producing. Godrich and Greenwood brought recording gear from England, turning a room at the fort into a makeshift studio, where they lived and recorded for three weeks; rehearsing and recording through the day and night.

Ben Tzur recounts the roots of the collaboration, with Greenwood hearing his music and instantly taking a liking to it, with a common friend then arranging for them to meet. "We had no agenda of doing something together. I think it just emerged out of a fascination for music and friendship. When I listen to the album, I feel this reflects in the music," says Ben Tzur, as I catch him on the phone a day before he has to leave India. He lives in Tel Aviv now, but Ben Tzur shares a deep relationship with India, and visits the country often, with his wife’s family also living in Ajmer, Rajasthan. "You could say that I have two homes."

A concert at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall with his group, featured Greenwood as a guest artist, and this solidified their intention of working on music together. He says: "It had been so much fun, so we thought of taking it forward. I had written a lot of material at the time, a lot of music."

They decided to record an album in India, but sitting in a studio to work on it was never a part of the plan. Instead, Ben Tzur began the search for a place that would be inspiring, that would, in some way, develop and emphasise the music. He knew Maharaja Gaj Singh of Jodhpur, briefly from prior concerts in India, and they’d been in contact on and off, which helped them get access to the majestic fortress.

Of the Rajasthani musicians, he says: "They’re people I’ve known for 15 years; they’re like family to me." He composed the songs before the recording began, rehearsing with the Indian musicians and sending across sketches to Greenwood and Godrich by way of pre-production work, but a lot of the music came to life inside the fort, with the place itself allowing for an incubation of the ideas. "I had kept it a little ‘loose’; everything sort of came together when we were playing there every day."

Ben Tzur’s past works have had a collaborative spirit, and the music resists rigidity and categorisation – Junun is no different. His poetry which forms the articulation of the music is devotional in nature, sung in Hebrew as well as in Hindi and Urdu, using the verses of Hazrat Nawab Mohammad Khadim Hasan Shah, a Sufi mystic, saint, and poet from Ajmer, Rajasthan. The compositions draw from Sufi and Qawwali traditions, as well as Arabic and western styles and modes as a strong rhythmic, percussive spine brings a constant movement filled with exhilarating energy.

"My major musical education happened in India," says Ben Tzur, "so I’m fascinated by the ragas and bandishes – the structure, the way things work in the traditional manner. With this kind of music, I’m aware of the different things you have to keep in mind while writing; it’s already embodied in my mind so I don’t compose with that thought. It’s always very interesting because it’s so rich. The aesthetics of the music are such that certain things could sound harsh if you don’t take into account some elements of Indian music. A lot of the tension is expressed within the raga and the scale, rather than in chord changes. So if we decide to use chords, it has to be in a very sensitive way otherwise you can kill the entire atmosphere you wanted to create. In Qawwali music, the composition, the melody, it’s always short, within which you try to express a lot.

"Greenwood is very, very curious about music and an amazing musician. We were discussing these things, and one of the main decisions we made was that we would try to use chords as sparingly as possible, and play more with rhythmic and ‘sound’ elements – try to rest and let the chords emerge from the melody rather than imposing, western chords on the music."

The guitar plays an influential role, guiding a lot of the pieces, but the songs seem to have a swirling kind of grace – an interplay of form – as the different singing styles waddle around the mix, the intensity of the percussion adding a roaring sense of drive (there are even electronics in there, a traditionally challenging form to blend with Indian music). The songs seem punctuated with thrilling bits of melodic elation added by the brass sections. It’s an exploratory, ambitious record, one that they haven’t tried to "package for any commercial purpose".

Ben Tzur is happy just to let the songs express themselves. It’s a sentiment vividly depicted in Junun, the new Paul Thomas Anderson documentary which charts the recording process of the album (and is currently doing the rounds of the film festival circuit). Anderson, with whom Greenwood frequently collaborates (having written the imperial scores for There Will Be Blood, The Master, and Inherent Vice), also came along with Greenwood, Godrich, and their technical crew to India. "There aren’t any manipulations in it," says Ben Tzur, talking about the film. "The power of it, for me, is that you see a group of people sitting and working on an album, and that is fascinating. It doesn’t matter if you like it or not; what’s presented is what’s really there, and that’s very special."

The film captures the spiritual quality of the record, and the care and devotion that seems to exist around it. All the musicians involved seemed to be at ease with the process, and Ben Tzur speaks further on working with the Indian musicians featured on Junun: "It was very exciting. All of them are committed and devoted to what they do. They’re very passionate musicians. It was amazing, not only to witness it but to be present in that situation. Music is still an oral tradition in India. People basically learn music as a language, not as a ‘hobby’ made into a ‘profession’. So it’s a whole different level of musician that you find in India. It’s something phenomenal."

The conclusion of the recording process coincided with the World Sacred Spirit festival, a Sufi and folk music festival held at the Mehrangarh fort. The musicians put up an affecting performance – Greenwood, in a previous interview with this writer for the Indian publication The Sunday Guardian called the music "joyful", as appropriate a description as any – displaying a sublime synchronicity and chemistry. Ben Tzur – in conversation, in the film, and on stage – asserts a gentle, understated kind of authority, at the same time displaying a humble deference to the power of the music. Playing, singing, and pretty much conducting the performance, there was a moment when the percussionists began one of the songs at a slightly faster tempo than expected, a natural reaction to the rush of playing on stage. Unperturbed, Ben Tzur turned around from his position at the front of the stage, indicating the correct tempo with his thumb and fingers, consequently acknowledging the shift and nodding in appreciation once the players got into the groove.

The group has performed together a few times – they recently played in Jerusalem as well – and they have a few concerts lined up in North America and Europe. He’s forever writing music, exploring different directions in sound, but he doesn’t much like to talk about future projects. "The album comes out; then there are some other things I’m working on, but I always like to keep it hidden until it comes out. Music happens all the time. I practice, I experience life, and music emerges."

Sincerity and depth – traits sadly derided in a postmodern world of irony – seem to define his troubadour-like approach to music, and indeed, to life too. Speaking about the troubled and politically charged conflict in Israel and the Middle-East region, Ben Tzur talks about peace and unity, almost with a forlorn air. "Being a musician and, first, a human being, and living in Israel and in that region, I can say that whatever’s happening these days is very sad; there’s violence and uprising and people are getting more and more political. The fact that I’m making music doesn’t put me in a position to give a better opinion than anybody else. But I would always try to hold on to the humanitarian aspect and come together with people. Sometimes it’s very hard, when there’s so much violence around, to try to hold on to the positive side, and to promote the feeling of love and humanity rather than jumping into that fire of hate. Instead of bringing people together and solving things, they’re just making more complicated decisions, so I’m very sad for the loss of life and for this situation."

Junun is out now on Nonesuch Records