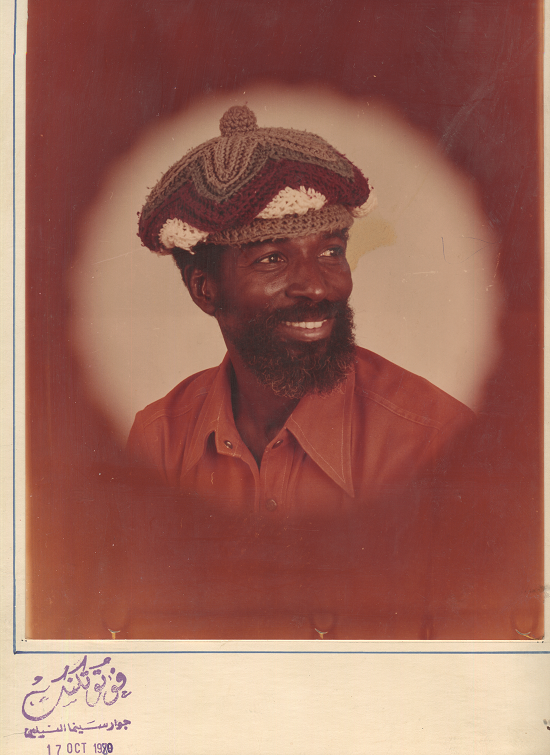

Sharhabil Ahmed in 1980

‘The King of Sudanese Jazz’ is not just a nickname for Sharhabil Ahmed, the way Madonna is ‘The Queen of Pop’ or Elvis ‘The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll’, it is a title that was literally bestowed upon him. He has a medal to prove it. On New Year’s Eve 1971 he was playing a show at St. James’ dance hall in Khartoum, the city’s biggest venue. “I was the star of the night,” he recalls. “While I was performing, the owner of the club stepped out from the dancing crowd, stood before the microphone and said, ‘We’re celebrating the New Year tonight, but let us also celebrate this great musician! His great, sweet, lovely and incomparable music! Do you agree?’ The crowd all shouted ‘Yes!’ and he took out of his pocket a golden necklace with a medallion inscribed with the title Malik Al Jazz – ‘The King of Jazz’.”

The King Of Jazz is also the name of a new compilation of Ahmed’s music, put out by Habibi Funk this year, a record that fizzes and cracks with electricity and energy, dominated by the musician’s extraordinarily charismatic vocal presence. Rather than straight-up jazz as it is known in the UK, the music is a mix of rock ‘n’ roll, funk and samba, as well as established Sudanese music. Habibi Funk first included its opener ‘Argos Farfish’, a blasting joy of a song, on their 2017 compilation An Eclectic Selection of Music From The Arab World. Around the same time, their sister label was working with a Sudanese MC called Zen-Zin, who happened to live next door to Ahmed’s son Mohamed, himself a musician. On their behalf Mohamed asked his father what he thought of remastering and re-releasing some of his best tracks, and after years spent searching for recordings in high enough quality, they emerged with one of the compilations of the year, yet one that still only scratches the surface of a remarkably storied career. tQ speaks to Ahmed via email, our questions printed out and delivered by his granddaughter Naryman Ehab for Ahmed to answer by hand, transcribed by Habibi Funk and then emailed back to tQ.

Ahmed was born in 1935 in Omdurman, though his family moved around the country frequently in line with his father’s truck driving job. What is now Sudan was then still under joint British and Egyptian control. A year later, the region’s status was left in limbo by Britain and Egypt’s Treaty of Alliance, establishing independence for the latter. It would be two decades until Sudan was recognised as a state of its own. At this time, the country’s traditional madeeh music, chant-based songs in praise of Allah and the Prophet Mohamed, was beginning to evolve in urban centres into a rhythmic secular successor called haqiba, which drew upon indigenous musical traditions and incorporated limited instrumental accompaniment and backing vocalists. Although Ahmed’s father was a stern and religious man, he nevertheless owned a phonograph and haqiba was regularly played at home. Despite his family’s reservations Ahmed became a keen musician in his own right, teaching himself the oud and learning traditional Sudanese, Egyptian and Indian songs.

The Republic Of Sudan gained independence in 1956 under a fractious coalition government, which was then overthrown by Ibrahim Abboud’s coup d’état two years later. Ahmed remembers these years as a time of optimism and cultural renaissance, the perfect backdrop for a budding musician. The soundtrack to parties and gatherings, haqiba had begun to produce stars like Abdullah Al-Magi, the first Sudanese singer to record his music, and Abdul-Karim Karouma, who a teenaged Ahmed saw perform at a wedding. In South Sudan, meanwhile, neighbouring Congolese musicians, themselves influenced by South American and Caribbean music, were beginning to bring over guitars. Ahmed had first seen the instrument in Westerns at the cinema, and later played by southern street performers in Al-Obeid, where his family eventually settled.

Ahmed graduated a graphic design course at the College of Fine Arts in Khartoum, and established a career in the Sudanese Ministry Of Education as an illustrator of children’s textbooks and magazines (something of a polymath, he found fame as an illustrator as well as a musician). While there, he re-encountered Reda Muhamed Ausman, who he’d known briefly while studying, and who was now general secretary for one of Ahmed’s employers, the young persons’ magazine Al-Sibyan. “He was a poet, and also a writer, and he loved music very much. During our work together, a strong friendship grew between us,” Ahmed remembers. “He discovered my second talent, that I loved singing and playing music, and he always told me that it was better than the singers we were listening to. But I always told Reda, becoming a singer is not an easy matter!”

Ausman and other colleagues at Al-Sibyan were a constant source of encouragement. They’d organise parties and picnics at the end of the working week and book Ahmed as their star performer. “Years and months passed by, and then one day Reda came into my office looking very gay and happy, holding a newspaper in his hand. He said to me, ‘I come to you with a beautiful surprise!’ and he began reading it to me.” Ausman pointed out an advertisement for a new singing competition, organised by Omdurman Radio. “I told Reda I’d never competed before, that I’d never composed my own songs before, but Reda said to me ‘This is a great chance for you, you’re very gifted, don’t let it go.’ Reda gave me a song that he wrote about [the Sudanese province] Korfodan called ‘The Nights Of Korfodan’. The competition was very hard, but I put in great effort. The committee only selected eight winners, and I was one of them. If it wasn’t for Rida, I would have never become a singer.”

Despite sudden popularity thanks to live performances on Omdurman Radio – they went on to broadcast ten more of his songs – Ahmed continued his day job and played mammoth shows in the evenings at the British-owned Gordon’s Music Hall. “I worked by day in the Ministry of Education, from seven in the morning until two in the afternoon, then I’d work nightly from nine in the evening up to three in the morning. It was difficult, but I enjoyed it.” A musical genius who also played the saxophone, trumpet and trombone, it was around this time he purchased a guitar of his own from a British salesman at a flea market, learning to play from some southern students. Transitioning from the oud “was a new test,” he remembers. “The guitar was a complete harmonic school, and has a beautiful, colourful tone. I started composing all of my music with it.”

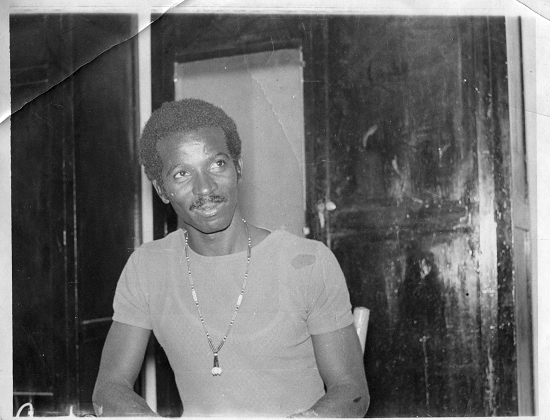

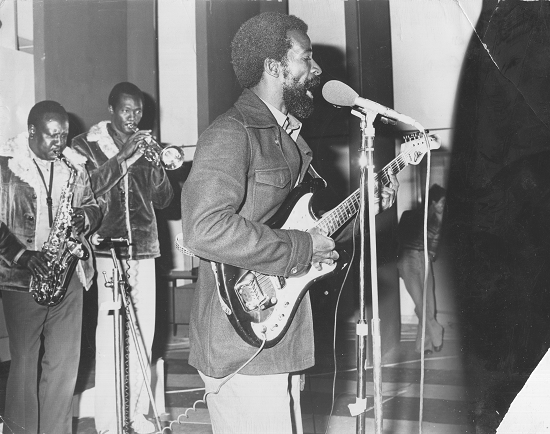

Sharhabil Ahmed and his band, 1963

For his performances on Omdurman Radio, however, he was required to play the oud and use the station’s in-house orchestra as his backing, “but for myself, I wanted to organise a band,” he says. “With a band I could be free to compose and play completely different styles of songs, using the guitar this time, imitating rock music and jazz but without changing the Sudanese melodic singing style.” In 1960, his newly formed band had their first hit with ‘Helwat Al Ainein’. The writer Zualnun Bushra asked them to write music for his lyrics, “to accompany a big, theatrical show,” that was to open the country’s National Theatre. “It became our first big hit, and we became the first jazz band in Sudan.” Following his lead, bands like The Blue Stars, The Scorpions, The Aldiyum Band and Al-Agarib turned the music into a movement. Eventually, Ahmed would lead efforts to form the country’s first musicians’ union, The Jazz Union.

By the mid-60s, such was Ahmed’s fame, that he performed in front of none other than Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, along with three other Sudanese singers hand-picked “to strengthen the friendship and brotherhood between the two countries,” as he remembers. “It was at the most beautiful theatre in Adiss Ababa, named after the Emperor himself, the Haile Selassie Theatre. That night we performed a really amazing show, the Emperor looked happy. I heard he whispered to our ambassador, ‘I want to see them here, to thank them for their performance,’ so our ambassador sent for us to meet his majesty. The manager of the theatre led us through corridors with red carpet to where the Emperor was sitting with all of his highest-ranked men. He rewarded each of us with a golden medallion, for each member of our band, and for me as well.”

One member of Ahmed’s band was his partner Zakiya, with whom he had grown up. “She knows everything about me and has been following my musical activities since the very beginning. She loves music too, she learned the lute, the clarinet and the mandolin, and I also taught her how to play the guitar. By the time I formed the band she had become a good player, so I thought I’d get her to join. She said ‘I don’t have any objection, but I’m afraid my father won’t allow it. So I said to her ‘don’t worry, we’ll get married, then nobody can object. We married in 1964, and she became an official member of the band.” She was the first female guitarist in Sudanese history.

Sharhabil Ahmed, his wife Zakiya and one of their children, 1980

Ahmed’s status as a musician, particularly one who married traditional Sudanese and Arabic music with rock ‘n’ roll, swing, tango and samba, varied along with his country’s politics. The days after independence and Abboud’s reign between 1958 and 1964 were “the best days of all,” he recalls. “His government had great care for the arts, culture and sport.” Ismail al-Azhari’s brief democratic reign between Abboud and Nimeiry was positive too. When Nimeiry’s government took over, arts and music were side-lined while he consolidated power, but for a time left unchecked. It was during this period that the country’s College Of Music And Drama was formed, and in which he was crowned King.

On the other hand, there was the reign of Omar Al-Bashir from 1989 until just last year, under whose ‘Al-Ingaz’ (salvation) regime, strict Islamic law was implemented, and the country’s education system overhauled. “From the beginning they were very hard on dealing with musicians, especially public parties,” Ahmed remembers. “The occasions were specifically not allowed to exceed three hours, and the police could arrive at any time with guns and order an artist to step down from the stage. Sometimes they would take our instruments and sound systems or shoot above the crowd with real bullets to try and stop us by force. It felt like the lives of artists were in great danger.”

Ahmed performs at Khartoum’s Dubai Club, 1987

Throughout the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the complete lack of recording companies in Sudan meant that Ahmed’s band was an entirely live act, although under Bashir shows were more muted than those of old. Playing for Sudanese communities across Africa, Europe and the Gulf, however, their performances could burn as intensely as ever. He remembers one show in Baghdad in 1988, part of a grand theatrical performance of the play Napata My Love written by the poet and actor Hashim Siddiq about the ancient Nubian kingdom of Napata, whose greatness rivalled that of ancient Egypt and is often a euphemism for Sudan. “It had singing, dancing, drama and comedy,” he remembers fondly. “It looked a little like an opera. We also had my son Skarif playing the drums.”

Today, with Sudan once again in a period of instability and transition after Bashir’s removal, “the government is still busy with its many political problems. Music and arts are still not their priorities.” Nevertheless, there is hope that another age may arrive in which Sudanese jazz can resurge in full force, music of which Sharhabil Ahmed remains the uncontested king.

Thanks to Jonathan Kim, Habibi Funk Records, Sharhabil Ahmed and his granddaughter Naryman Ehab for their extraordinary efforts facilitating this interview. Habibi Funk’s new compilation The King of Sudanese Jazz is out now and can be purchased digitally and on vinyl here.