Ishmael Butler, the multi-monikered vocalist of Seattle-based hip hop outfit Shabazz Palaces is not known for his desire to elucidate on the duo’s musical output. In fact, in the early days of Shabazz, the identity of fellow band member Tendai Maraire as well as those of collaborators were kept anonymous, interactions with journalists were few and far between and press shots were practically non-existent. Far from a cynical marketing ploy, it came from a will to let the music alone do the talking, and a reaction against the trend for narrative-driven self-aggrandising which placed context above the music that artists were actually producing.

Although Butler’s stance has somewhat softened after self-released EPs Eagles Soar, Oil Flows and The Seven New and albums Black Up and July’s Lese Majesty (put out through Seattle’s forward-thinking but predominantly indie and rock-led label Sub Pop), it’s clear he’s still uncomfortable making statements about the duo’s back story or how listeners should interpret their latest offering. "A picture’s worth a thousand Swerves," he raps in Lese Majesty‘s ‘They Came In Gold’, clearly a dig at the industry culture that places the worth of the artist’s image above the work – in this case Black Up‘s ‘Swerve’. You only have to tot up the number of similes Butler spouts in our interview to notice that he’s a man who prefers not to talk specifics.

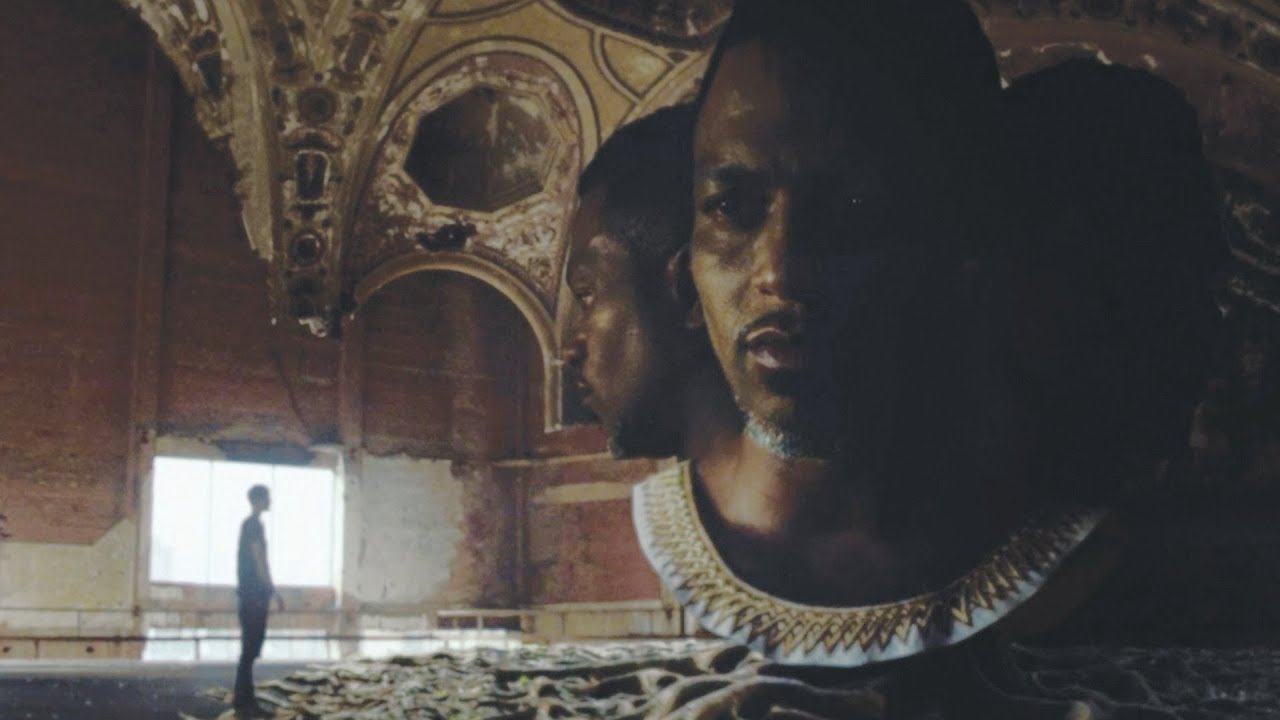

But unpacking Lese Majesty is a tricky business. Sonically, it’s a chaotic patchwork of dark soundscapes and sci-fi synths, doped beats that slip into more traditional sultry grooves, and tribal percussion that unexpectedly arrives at energetic Miami bass. Recorded in a dilapidated old brewery that the duo transformed into a studio, Lese Majesty eschews standard verse-chorus structure, instead shifting from sonic space to sonic space with exciting and sometimes disorienting results.

Linguistically too, it’s far from straightforward. Butler’s complex tangles of lyric, repetition and imagery offer glimpses of meaning and familiarity that fade and disappear just as quickly as they reveal themselves. Constant allusions to masks, identity and ego mingle among quotes from Moby Dick and samples from poet Lightning Rod, and there’s a host of neat linguistic plays. In ‘Dawn In Luxor’ for example, Butler riffs on ‘Kush’, nodding both to cannabis and the African kingdom that neighboured Ancient Egypt – itself a huge Afrofuturist reference point. For Butler, words are often used as a palette to create mood, to set a framework for listeners to delve into their own thought patterns or preoccupations. But this haze of meaning also makes moments of clarity all the more poignant. It’s tough to think of a more straightforward and understated way of describing the buzz of initial romantic affection than the line, "We should touch and agree" (repeated frequently in ‘Neotic Noiromantics’). As Butler himself espouses, it’s "more complex how my patterns map".

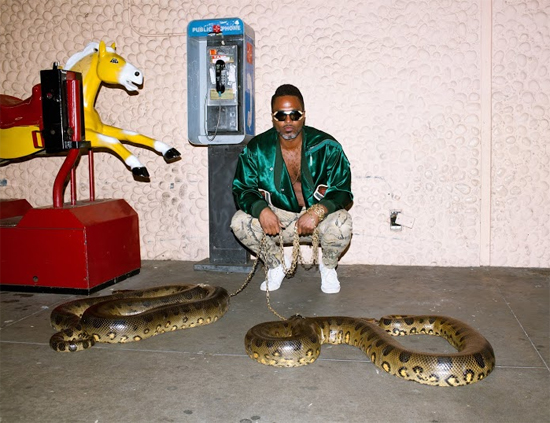

Just after the release of Lese Majesty, the Quietus caught up with Butler to talk about latest single (with its accompanying psychedelic horror video) ‘#CAKE’, Seattle and telepathy.

Do you feel that Lese Majesty is a departure from or evolution of Black Up?

Ishmael Butler: I guess I understand why people want to compare the last thing you did to the newest thing you did, but never really understand why. It’s not like you wake up in the morning and you put some clothes on, you go to a party, and people are like, ‘Why are you wearing that when you wore this the other day?’ Yeah, it doesn’t have anything to do with Black Up really.

But I guess although you might not wear exactly the same T-shirt, there might be correlation between your style one day to the next or where you like to shop…

IB: Yeah, I guess some artists have to stick with a certain sound or formula because their fans are people who are more prone to look at music and culture like they look at buying dishwasher liquid. They want that fit or familiar feel otherwise they don’t feel like it’s the product that’s been advertised to them. We don’t really have that kind of stigma attached to us. I’m sure some people will hear it and be like, "Ah, it’s not Black Up" but if they were looking for that, I don’t know what to tell them. [He laughs] I’m sorry!

It’s a really interesting record structurally. What made you decide to separate it into seven suites?

IB: The structure was something that developed, it’s not something that we blueprinted out and then filled with content like pouring cement. The titles and suites came about because certain sonic patterns pronounced themselves, and we started to see that certain tracks went with each other. Sometimes names have got something to do with creativity or you might just be high one day and something sounds good. There’s not a plan, it’s just a filling out of certain things, letting instinct prevail. Whatever conversation you’re having with the spirits and the universe where ideas and shit come from, you just grab on to them put them down and then move on.

So there’s not a significance to the number seven?

IB: Oh, there is a significance to the number seven for sure. We all know what that is, or have our own thoughts and perceptions about what that number means to us to us specifically. It’s important to us but I don’t think it’s important to the story of this music.

I thought it was interesting looking at the artwork for the record – the suites are actually mapped out architecturally like rooms in a building. Is that relevant to how you saw the record come together, or were you developing patterns in other ways?

IB: Unbeknown to myself maybe, but I don’t have that kind of intelligence to see those things ahead of time. I will say this, the brother than did that, Nep Sidhu, he is an architect. He listened to the album before it was done and we had conversations together about it as friends. He always comes up with things that when I see them I relate to them and recognise but I would never have come up with them myself. We’re brothers and we’re kind of telepathically linked, in the sense that where my skill set and his skill set meet, they have characteristics that are very similar.

Lyrically, Lese Majesty is quite illusive in places. How important is ambiguity in your work and using words to create mood rather than meaning?

IB: That’s interesting. The way I see it is this: a mood is much more specific, and has more weight, than a word or something that is telling you what to feel rather than providing the space for you to feel what you’re going to feel inside of it. So ambiguity in a way is more specific than the way that you have been trained to understand lyric or melody. For me, exciting music, reading or artwork is something that doesn’t instruct me but provides for me a place where I can find out something more about myself or the way that I feel, rather than telling me this is what you’re meant to feel by experiencing this thing. We try to facilitate that. It’s not even about being really ambiguous, I’m not even smart enough to do that. I’m being as specific as I can, but it’s just the style that I’ve honed over the years lends itself to this kind of output. This is the way the land lies for us.

There’s a lot of allusions to being your true self in the record and yet you’re interested in anonymity, and almost a kind of linguistic disguise. How to those two things balance out?

IB: I don’t know the answers. This endeavour, our compulsion to make music, is also just cats getting together and searching for answers ourselves. This whole notion that musicians have information and are channelling into some higher understanding, though true, it’s not specific to them. These people don’t have the answers, they’re not deities. The music is not coming out of us, it’s happening to us. We’re traveling coinciding with everyone that’s listening to it. We’re searching as well.

Is the idea of the musician as a ‘deity’, or perhaps just a ‘celebrity’ something that concerns you? In the early days of Shabazz Palaces you didn’t name band members and collaborators…

IB: Some musicians are deities, but most of them that are self-proclaimed whatever, the ‘greatest’, they’re not. But that’s now more of a marketing thing than people being serious. A lot of people have self-absorbed feelings about themselves or their contribution to society or culture. At first it was like a ‘me-mania’ sweeping over Western quote-unquote civilised nations and now permeating throughout the world. You, your Facebook, your Twitter, your Instagram or whatever devices you’re using to keep those up – it’s just "me me me, I’m this, I’m that". Everyone’s crazy over photos they took on their iPhone, it’s wild shit. There are really superficial, unnecessary things that are being passed off as culture. I understand that, I’m not dissing it, I got my feelings about it, but I don’t think that overall it’s weak and corny, although there’s a lot of weakness and corniness that’s involved in it. Early in Shabazz, we just wanted to make the music and let the music be what it was and forget about all the other anecdotal backstory marketing stuff and see what happened. It was more about that than being purposely mysterious.

Do you feel more relaxed about talking about your history and your backstory now?

IB: Not really. I don’t think it really matters, but again it wasn’t about being mysterious. I’m not going to bust around acting like I’m not going to talk about it just to be difficult.

Do you want to tell me about some of the ideas you wanted to explore in Lese Majesty?

IB: No, not really. If they’re there, they’re there to be mined by people rather than for me to issue some statement about what they are.

What about the production then, it’s a lot weirder than Black Up. Were there new sonic avenues that you wanted to explore?

IB: Yes, but a lot of that is intimate. The record is like a marathon. You run with as much strength as you can for a very long period of time, even when you’re on tour for a year pretty much, or three years as is our case. Your mind’s always in a constant state of composing, but you’re not getting into the studio that much. That traveling of your mind is just as integral to the final product as actually recording. When you take time off to record and you get in the studio and it’s kind of like the end of the race when you’re sprinting to the finish line.

Yeah, I can really feel that sense of it gathering over time, especially in ‘#Cake’. I really love the production on that track, it hops between this psychedelic, almost woozy feel, to then to an Anquette-like Miami Bass vibe, then there’s the lovely interludes from Cat Harris-White. What inspired that track and how did come together?

IB: Well, you describe it better than I could [he laughs and then pauses].

Perhaps tell me about how you and Cat started working together then?

IB: THEESatisfaction were local legends on the scene and I hadn’t heard or seen them yet until my bro told me, "You got to check them out". The first time I met them it wasn’t at a concert but at an art opening, where Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes had this spot called Punctuation. We had been destined to be together for quite some time. We finally met and started making music together and just hung out. This was probably 2008. We loved talking about the world and having fun with each other. Sometimes we’d find ourselves in the studio, sometimes we were on tour, but there’s always a vibration coming out of her. When that track was being constructed, there was a certain part on there… I always hear Cat singing in my head, and that was one of the times where everything coincided and we were able to put something on record.

THEESatisfaction are also in The Black Constellation with you…

IB: Yeah. Black Constellation is artists of all disciplines that see the world similarly, get along with each other and have a desire to protect and exalt our culture, that’s African, American, musicians, men, women, lovers and livers of life. We’ve been around since the beginning of time in different incarnations and we have been fortunate enough to find each other in this time. We challenge, support and inspire each other to pursue our passions. We’ve all made it better for each other.

Tell me more about the Ode To Octavia films you made with Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes and THEESatisfaction. What was it about [sci-fi writer] Octavia Butler’s work that particularly inspired you to make the series?

IB: The brilliance, the strength, the imagination, the selflessness of her work. Her writing inspired and spoke to me and kept me company and sparked my imagination. We all have personal feelings but they all fall under that description about her. We come together on that. She’s been a mother and a mentor to us. We owed it to her basically.

Do you see Shabazz as part of a similar lineage, part of an ‘Afrofuturist’ body of work?

IB: I think it’s for someone else to say other than me but I know that… I’m a product of it. I wouldn’t call it ‘Afrofuturism’ because I don’t really know what that means. But Sun Ra, Miles, and countless other people that never heard of ‘Afrofuturism’, I’ve learned from their gleanings.

There are a lot of nods to Ancient Egypt on the record, obviously an important reference point for that movement, but a lot of the tracks (‘They Come in Gold’ especially) simultaneously deal with wealth, dissent, ego… I wondered whether there was any correlation between the struggle that the modern nation is having with corruption, with Hosni Mubarak imprisoned for embezzlement… or am I reading far too much into it?

IB: No, I think it’s a compliment what you’re reading into it. The function of art is to do just that. Even if these parallels aren’t noticed and recognised by the people making it, the fact that they exist corroborates the connection even more than if it was common. Telepathy has been replaced by our notion of technology. Instead of being able to think along wavelengths and connect that way we’ve made devices that do it for us. In actuality there’s always been a ‘World Wide Web’, a network of telepathic feelings that if you’re tuned into – and open to this conversation with the universe – patterns develop. I knew what was going on in Egypt and I followed it in a superficial, marginal way, but I didn’t have to follow it because I’m in tune with it, me and my peoples are in tune with it, and we’re living a version of it ourselves where we’re at. That you saw it is keen on your part, because than energy you saw is very real even though I hadn’t even thought of [the record] that way.

You self-released your first two EPs before signing to Sub Pop. At the time it was quite an unorthodox signing for them in some ways because they are traditionally more of an indie label. Are you still finding it a comfortable fit?

IB: Yeah, it definitely is. Sub Pop is a singularly unique entity in the sense that their approach to the business of music is that everyone, from the people who work for the label to those that record on it, share a passion, a love and energy for music. They create an environment that’s comfortable. It’s serious and hard work is expected, but creativity in both business and the product is expected too. It’s an environment unlike any other. I love it.

How do you feel about the general health of hip hop in Seattle? You obviously see a lot of new talent helping Sub Pop with A&R…

IB: Yeah it’s really diverse, there’s quite a few interesting people making music. But Sub Pop is international too. We’ve got people from all over the world signed here. We do keep an eye on things locally of course, and have a lot of pride and love for the city, but it extends all around the world as well.

Is your working relationship with Tendai [Maraire] something you anticipate continuing for a long time?

IB: Yeah, he’s my bro. He raps as well, and he’s got musical ideas that he wants to pursue himself that he’s doing with his Chimurenga Renaissance, but in terms of our musical brotherhood I’m sure it will continue through the years. We relate telepathically. It’s rare that you find someone that you communicate with like that. We’ll always be down.

Shabazz Palaces’ Lese Majesty is out now via Sub Pop